Himalayan and Central Asian Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Negi R, Baig S, Chandra A, Verma PK, Naithani HB, Verma R & Kumar A. Checklist of Family Poaceae in Lahaul and Spiti Distr

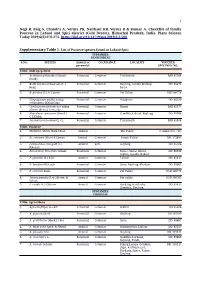

1 Negi R, Baig S, Chandra A, Verma PK, Naithani HB, Verma R & Kumar A. Checklist of family Poaceae in Lahaul and Spiti district (Cold Desert), Himachal Pradesh, India. Plant Science Today 2019;6(2):270-274. https://doi.org/10.14719/pst.2019.6.2.500 Supplementary Table 1. List of Poaceae species found in Lahaul-Spiti SUBFAMILY: PANICOIDEAE S.No. SPECIES Annual or OCCURANCE LOCALITY VOUCHER perennial SPECIMEN NO. Tribe- Andropogoneae 1. Arthraxon prionodes (Steud.) Perennial Common Trilokinath BSD 45386 Dandy 2. Bothriochloa ischaemum (L.) Perennial Common Keylong, Gondla, Kailing- DD 85472 Keng ka-Jot 3. B. pertusa (L.) A. Camus Perennial Common Pin Valley BSD100754 4. Chrysopogon gryllus subsp. Perennial Common Madgram DD 85320 echinulatus (Nees) Cope 5. Cymbopogon jwarancusa subsp. Perennial Common Kamri BSD 45377 olivieri (Boiss.) Soenarko 6. Phacelurus speciosus (Steud.) Perennial Common Gondhla, Lahaul, Keylong DD 99908 C.E.Hubb. 7. Saccharum ravennae (L.) L. Perennial Common Trilokinath BSD 45958 Tribe- Paniceae 1. Digitaria ciliaris (Retz.) Koel Annual - Pin Valley C. Sekar (loc. cit.) 2. D. cruciata (Nees) A.Camus Annual Common Pattan Valley DD 172693 3. Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) Annual Rare Keylong DD 85186 P.Beauv. 4. Pennisetum flaccidum Griseb. Perennial Common Sissoo, Sanao, Khote, DD 85530 Gojina, Gondla, Koksar 5. P. glaucum (L.) R.Br. Annual Common Lahaul DD 85417 6. P. lanatum Klotzsch Perennial Common Sissu, Keylong, Khoksar DD 99862 7. P. orientale Rich. Perennial Common Pin Valley BSD 100775 8. Setaria pumila (Poir.) Roem. & Annual Common Pin valley BSD 100763 Schult. 9. S. viridis (L.) P.Beauv. Annual Common Kardang, Baralacha, DD 85415 Gondhla, Keylong SUBFAMILY: POOIDEAE Tribe- Agrostideae 1. -

Himalayan Aromatic Medicinal Plants: a Review of Their Ethnopharmacology, Volatile Phytochemistry, and Biological Activities

medicines Review Himalayan Aromatic Medicinal Plants: A Review of their Ethnopharmacology, Volatile Phytochemistry, and Biological Activities Rakesh K. Joshi 1, Prabodh Satyal 2 and Wiliam N. Setzer 2,* 1 Department of Education, Government of Uttrakhand, Nainital 263001, India; [email protected] 2 Department of Chemistry, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, AL 35899, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-256-824-6519; Fax: +1-256-824-6349 Academic Editor: Lutfun Nahar Received: 24 December 2015; Accepted: 3 February 2016; Published: 19 February 2016 Abstract: Aromatic plants have played key roles in the lives of tribal peoples living in the Himalaya by providing products for both food and medicine. This review presents a summary of aromatic medicinal plants from the Indian Himalaya, Nepal, and Bhutan, focusing on plant species for which volatile compositions have been described. The review summarizes 116 aromatic plant species distributed over 26 families. Keywords: Jammu and Kashmir; Himachal Pradesh; Uttarakhand; Nepal; Sikkim; Bhutan; essential oils 1. Introduction The Himalya Center of Plant Diversity [1] is a narrow band of biodiversity lying on the southern margin of the Himalayas, the world’s highest mountain range with elevations exceeding 8000 m. The plant diversity of this region is defined by the monsoonal rains, up to 10,000 mm rainfall, concentrated in the summer, altitudinal zonation, consisting of tropical lowland rainforests, 100–1200 m asl, up to alpine meadows, 4800–5500 m asl. Hara and co-workers have estimated there to be around 6000 species of higher plants in Nepal, including 303 species endemic to Nepal and 1957 species restricted to the Himalayan range [2–4]. -

Lahaul, Spiti & Kinnaur Substate BSAP

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY SUB- STATE SITE BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN (LAHAUL & SPITI AND KINNAUR) MAY-2002 SUBMITTED TO: TPCG (NBSAP), MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT & FOREST,GOI, NEW DELHI, TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT, H.P. SECRETARIAT, SHIMLA-2 & STATE COUNCIL FOR SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT, 34 SDA COMPLEX, KASUMPTI, SHIMLA –9 CONTENTS S. No. Chapter Pages 1. Introduction 1-6 2. Profile of Area 7-16 3. Current Range and Status of Biodiversity 17-35 4. Statement of the problems relating to 36-38 biodiversity 5. Major Actors and their current roles relevant 39-40 to biodiversity 6. Ongoing biodiversity- related initiatives 41-46 (including assessment of their efficacy) 7. Gap Analysis 47-48 8. Major strategies to fill these gaps and to 49-51 enhance/strengthen ongoing measures 9. Required actions to fill gaps, and 52-61 enhance/strengthen ongoing measures 10. Proposed Projects for Implementation of 62-74 Action Plan 11. Comprehensive Note 75-81 12. Public Hearing 82-86 13. Synthesis of the Issues/problems 87-96 14. Bibliography 97-99 Annexures CHAPTER- 1 INTRODUCTION Biodiversity or Biological Diversity is the variability within and between all microorganisms, plants and animals and the ecological system, which they inhabit. It starts with genes and manifests itself as organisms, populations, species and communities, which give life to ecosystems, landscapes and ultimately the biosphere (Swaminathan, 1997). India in general and Himalayas in particular are the reservoir of genetic wealth ranging from tropical, sub-tropical, sub temperate including dry temperate and cold desert culminating into alpine (both dry and moist) flora and fauna. -

45354-002: Building Climate Resilience in the Pyanj River Basin

ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING REPORT _________________________________________________________________________ April 2021 Annual report Project No. 45354-002 Grant: G0352 Reporting period: 1 January 2020- 31 December 2020 TAJIKISTAN: "BUILDING CLIMATE RESILIENCE IN THE PYANJ RIVER BASIN" Component 1 and 2 (irrigation and flood management) (Financing by the Asian Development Bank) Prepared by the Agency for Land Reclamation and Irrigation under the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan (Project Implementation Unit) for the Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of ADB's Board of Directors, its managers, or employees, and may in fact only be preliminary. When preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by any indication or reference to a specific territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments regarding the legal or any other status of any of territories or districts ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank. ALRI Agency for Land Reclamation and Irrigation. CEP Committee on Environment Protection TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose of the report ................................................................................................................. 2 2 ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING ................................................................................................ -

Diversity of Herbs in Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary of Distt. Lahaul and Spiti

Biological Forum – An International Journal 12(2): 01-12(2020) ISSN No. (Print): 0975-1130 ISSN No. (Online): 2249-3239 Diversity of Herbs in Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary of Distt. Lahaul and Spiti, Himachal Pradesh Ranjeet Kumar, Raj Kumar Verma, Suraj Kumar, Chaman Thakur, Rajender Prakash, Krishna Kumari, Dushyant and Saurabh Yadav Himalayan Forest Research Institute, Panthaghati, Shimla (Himachal Pradesh), India. (Corresponding author: Ranjeet Kumar) (Received 09 June 2020, Accepted 29 July, 2020) (Published by Research Trend, Website: www.researchtrend.net) ABSTRACT: The cold desert in Himalayas are home of unique and threatened plants. The landscapes of cold deserts are rich in biodiversity due to unique topography, climatic conditions and variation in plant diversity in different habitats. The plant diversity provides information on plant wealth of particular area. The present investigation was conducted to know the phytodiversity of herbs in Kibber Beat of Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary (KWLS) during 2017-2019. The study included dominance of vegetation, diversity indices and documentation of threatened plants. Total 12 communities, 22 family, 50 genera and 71 species were recorded during the study in Kibber Beat of the Sanctuary. Total 4 numbers of threatened plants were recorded viz., Arnebia euchroma, Berginia stracheyi, Physochlaena praealta and Rhodiola heterodonta. Total density/m2 of herbs varied from 7.35 to 54.85. Maximum value of diversity index (H) in communities was 2.84 and minimum was 1.81. Ex-situ conservation of plants is required to conserve the diversity of plants of the cold desert. Keywords: Cold desert, Kibber, herbs, community and phytosociology. I. INTRODUCTION wild annual and perennial herbs followed by dwarf bushes or shrubs (Saxena et al., 2018). -

Final Report Reducing Human-Snow Leopard Conflict in Upper Spiti

Conservation Leadership Programme: Final Report Reducing Human-Snow Leopard Conflict in Upper Spiti Valley, India. Conservation Follow-up Award Project ID: 2462 Host country: India Site: Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India Dates in field: May 2015 to April 2017 Names of author(s): 1. Kulbhushansingh Suryawanshi 2. Rishi Sharma 3. Radhika Timbadia 4. Ajay Bijoor 5. Kalzang Gurmet Contact address: Nature Conservation Foundation, 3076/5 IV Cross, Gokulam Park, Mysore (Karnataka), 570002 Tel: +91 821 2515601 Fax: +91 821 2513822 Correspondence Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Website: http://ncf-india.org/ Date: 31 August 2017 Contents Summary & Background ......................................................................................................................... 3 Objectives, Activities and Outputs .......................................................................................................... 5 Achievements and Impacts ................................................................................................................... 14 Problems encountered and lessons learnt ........................................................................................... 15 Stories and Anecdotes from the Field................................................................................................... 18 Future planned activities ...................................................................................................................... 22 Appendices ........................................................................................................................................... -

Building Climate Resilience in the Pyanj River Basin

Bi-annual Environmental Monitoring Report April 2017 Grant 0352-TAJ: Building Climate Resilience in the Pyanj River Basin Prepared by the Agency for Land Reclamation and Irrigation under the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan The bi-annual environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. BI-ANNUAL ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING REPORT ______________________________________________________________ Project Number 45354-002 G0352 Grant: G0352 Reporting period: July – December 2016 TAJIKISTAN: «BUILDING CLIMATE RESILIENCE IN THE PYANJ BASIN» Component 1 и 2 (Irrigation and flood management) (Financed by the Asian Development Bank) Prepared by the Agency for Land Reclamation and Irrigation under the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan (Project implementation center) for Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a borrower's document. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the ADB Board of Directors, its managers or employees, and can in fact bear only a preliminary nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing a project, -

Delhi Rape(E)

AUGUST 2013 ● ` 30 CHILD LABOUR FOR GO-AHEAD MEN IN INDIA: AND FAILINGFAILING LAWSLAWS DOMESTIC VIOLENCE: WOMEN SOFT TARGET ALONG THE ANCIENT ROUTE: REDISCOVERING GLORIOUS PAST WIMBLEDON 2013: RISING NEW STARS FIDDLING WITH AFSPA: APPEASEMENT IN DISGUISE INFANT MORTALITY: SHOCKING STATS INTERNATIONAL 10 10 50 years of women in space 73th year of publication. Estd. 1940 as CARAVAN 78 Their patience and perseverance paid off AUGUST 2013 No. 370 90 Massacre-squads NATIONAL 104 US to arm India! 20 ECONOMY ● ENTERPRISE 8 Ganging up of netas against electoral reforms 68 Just a mouse-click away 20 Child labour today 94 Closure of bank branches 23 Controlling child labour 95 An Idea can change your life 36 Another look at domestic 96 Solar energy highways violence MIND OVER MATTER 42 Dowry? 110 52 Demise of day-old infants in 26 Aunt relief India appaling 56 A heart-warming end to a 54 Stop fiddling with AFSPA harrowing journey 106 Elder abuse, some harsh facts 110 Aparta LIVING FEATURES 46 16 Are you in the middle rung? 4 Editorial 86 Fun Thoughts! 18 Creativity and failed love 13 My Pet Peeve 98 Viable solution 32 Are you caught into 14 Automobiles to parliament hung “I will do it later” Trap? Round the Globe (Poem) 46 India’s maverick missile woman 17 Human Grace 100 Women All 58 Discovering the origin of 29 Child Is A Child the Way Aryan Culture Is A Child 107 Shackles of 62 Doing yeoman service 30 The World in Superstition 64 Boxers’ pride 108 Pictures 109 My Most 66 Sassy & Sissy 34 Way in, Way out Embarrassing 72 Elegy to TMS 70 Gadgets & Gizmos Moment 74 Out of sight, not of mind 84 New Arrivals 113 Letters CONTENTS 76 Shamshad Begum 88 Visiting Srivilliputhur forest For some unavoidable reasons 92 From the diary of a ‘gigolo’ Photo Competition has to be dropped in this issue. -

5Ef780bee15ef.Pdf

y k y cm WATER BABY SEROLOGICAL SURVEY EXTRADITION NOT EASY Actor Shruti Haasan took to Instagram, where she A serological survey for comprehensive Mumbai attack convict David Headley can’t be shared a throwback picture of herself from analysis of the spread of Covid-19 in extradited to India, a US attorney tells a federal court an underwater photo-shoot LEISURE | P2 Delhi has commenced TWO STATES| P7 INTERNATIONAL | P10 VOLUME 10, ISSUE 87 | www.orissapost.com BHUBANESWAR | SUNDAY, JUNE 28 | 2020 12 PAGES | `4.00 IN DELHI, ‘KEEP DOORS, WINDOWS CLOSED’ WINGED MENACE: As People have been directed to keep National capital’s IGI Airport has their doors and windows closed and been kept on high alert following swarm crop-destroying desert cover outdoor plants with plastic of locusts were spotted near to the key sheets. The District Magistrates have installation. The spotting took place near locusts swarms are also been asked to be on high alert. to NH 8’s stretch which connects the spotted in Delhi, the govt “District Magistrates are advised national capital to Gurgaon around to deploy the adequate staff to make 11.00 a.m., sources said. issues precautionary all possible arrangements for guid- Accordingly, the airport was kept at ing the residents to distract the lo- high alert as operations could have advisory. National custs,” the advisory by agriculture been affected due to the incoming lo- capital’s IGI Airport joint director AP Saini stated. cust swarm. However, due to a change The government said that they can in wind direction the swarm has moved has also been kept on be distracted by way of making high in a completely different direction For 21 days in a decibel sound through beating of drum altogether. -

Bi-Annual Environmental Monitoring Report

BI-ANNUAL ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING REPORT ______________________________________________________________ Project Number: 45354-002 Grant: G0352 Reporting period: January – June, 2017 TAJIKISTAN: «BUILDING CLIMATE RESILIENCE IN THE PYANJ RIVER BASIN» Component 1 и 2 (Irrigation and flood management) (Financed by the Asian Development Bank) Prepared by the Agency for Land reclamation and Irrigation under the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan (Project implementation center) for Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a borrower's document. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the ADB Board of Directors, its managers or employees, and can in fact bear only a preliminary nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing a project, or by any indication or reference to a particular territory or geographical area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments about the legal or any other status of any of the Territories or areas 1 The Agency for land reclamation and irrigation under the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan Project management office (PMO) BCRPRB BIANNUAL PROJECT PROGRESS REPORT ON ECOLOGY for 6 months (from January 1 to June 30, 2017) " BUILDING CLIMATE RESILIENCE IN THE PYANJ RIVER BASIN, TAJIKISTAN" Components 1 and 2 (Grant 0352-TAJ) Dushanbe, 2017 2 CONTENT I INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 Project description 6 1.2 Objectives and methodology of the biannual progress report 6 1.3 Review of the project 7 1.4 Changes in project organization and the environment management team 8 1.5 Contract - Construction Supervision Services 10 1.6 Interaction with the Contractor, owners, etc. -

Socio-Political Change in Tajikistan

Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Philosophie Dissertation for the Obtainment of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Universität Hamburg Fachbereich Sozialwissenschaften Institut für Politikwissenschaft University of Hamburg Faculty of Social Sciences Institute for Political Science Socio-Political Change in Tajikistan The Development Process, its Challenges Since the Civil War and the Silence Before the New Storm? By Gunda Wiegmann Primary Reviewer: Prof. Rainer Tetzlaff Secondary Reviewer: Prof. Frank Bliss Date of Disputation: 15. July 2009 1 Abstract The aim of my study was to look at governance and the extent of its functions at the local level in a post-conflict state such as Tajikistan, where the state does not have full control over the governance process, particularly regarding the provision of public goods and services. What is the impact on the development process at the local level? My dependent variable was the slowed down and regionally very much varying development process at the local level. My independent variable were the modes of local governance that emerged as an answer to the deficiencies of the state in terms of providing public goods and services at the local level which led to a reduced role of the state (my intervening variable). Central theoretic concepts in my study were governance – the processes, mechanisms and actors involved in decision-making –, local government – the representation of the state at the local level –, local governance – the processes, mechanisms and actors involved in decision- making at the local level and institutions – the formal and informal rules of the game. In the course of my field research which I conducted in Tajikistan in the years 2003/2004 and in 2005 I found that the state does not provide public goods and services to the local population in a sufficient way. -

A History of Inner Asia

This page intentionally left blank A HISTORY OF INNER ASIA Geographically and historically Inner Asia is a confusing area which is much in need of interpretation.Svat Soucek’s book offers a short and accessible introduction to the history of the region.The narrative, which begins with the arrival of Islam, proceeds chrono- logically, charting the rise and fall of the changing dynasties, the Russian conquest of Central Asia and the fall of the Soviet Union. Dynastic tables and maps augment and elucidate the text.The con- temporary focus rests on the seven countries which make up the core of present-day Eurasia, that is Uzbekistan, Kazakstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Sinkiang, and Mongolia. Since 1991, there has been renewed interest in these countries which has prompted considerable political, cultural, economic, and religious debate.While a vast and divergent literature has evolved in consequence, no short survey of the region has been attempted. Soucek’s history of Inner Asia promises to fill this gap and to become an indispensable source of information for anyone study- ing or visiting the area. is a bibliographer at Princeton University Library. He has worked as Central Asia bibliographer at Columbia University, New York Public Library, and at the University of Michigan, and has published numerous related articles in The Journal of Turkish Studies, The Encyclopedia of Islam, and The Dictionary of the Middle Ages. A HISTORY OF INNER ASIA Princeton University Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , United Kingdom Published in the United States by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521651691 © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright.