Final Report Reducing Human-Snow Leopard Conflict in Upper Spiti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Border Trade: Reopening the Tibet Border Claude Arpi the First Part of This Paper Concluded with This Question: Can the Borders

Border Trade: Reopening the Tibet Border Claude Arpi The first part of this paper concluded with this question: can the borders be softened again? Can the age-old relation between the Tibetans and the Himalayans be revived? The process has started, though it is slow. This paper will look at the gains acquired from the reopening of the three land ports, but also at the difficulties to return to the booming trade which existed between Tibet and India before the invasion of Tibet in 1950 and to a certain extent till the Indo-China war of 1962. It will also examine the possibility to reopen more land ports in the future, mainly in Ladakh (Demchok) and Arunachal Pradesh. Tibet’s Economic Figures for 2012 According to a Chinese official website, the Tibetan Autonomous Region is economically doing extremely well. Here are some ‘official’ figures: • Tibet's GDP reached 11.3 billion US $ in 2012, an increase of 12 % compared to the previous year (Tibet's GDP was 9.75 billion US $ in 2011 and 8.75 billion US $ in 2010). • Tibet's economy has maintained double-digit growth for 20 consecutive years. • Fixed asset investment have increased by 20.1 % • The tax revenues reached 2.26 billion US $ (fiscal revenue grew by 46%) • And Tibet received over 11 million domestic and foreign tourists earning 2.13 billion US $ Tibet’s Foreign Trade Figures for 2012 The foreign trade is doing particularly well. On January 23, 2013, Xinhua announced that Tibet has registered new records in foreign trade. A Chinese government agency reported that the foreign trade of the Tibetan Autonomous Region reached more than 3 billion U.S. -

SEEK a SNOW LEOPARD; SPITI, HIMACHAL PRADESH Feb 9- 21, 2014 12 Nights 13 Days

SEEK A SNOW LEOPARD; SPITI, HIMACHAL PRADESH Feb 9- 21, 2014 12 nights 13 days Photo from thewildlifeofindia.com Known throughout the world for its beautiful fur and shy, elusive behavior, the endangered snow leopard (Panthera uncia) is found in the rugged mountains of Central Asia. Snow leopards are perfectly adapted to the cold, barren landscape of their high-altitude home, but human threats have created an uncertain future for the cats. Despite a range of over 2 million km2, there are only between 4,000 and 6,500 snow leopards left in the wild. On this trip we search for a snow leopard in the highlands of Spiti valley. Rudyard Kipling describes Spiti in "Kim" in these words: "At last they entered a world within a world - a valley of leagues where the high hills were fashioned of the mere rubble and refuse from off the knees of the mountains... Surely the Gods live here. The valleys of Kullu and Lahaul bound Spiti, locally pronounced “Piti”, on its south and west; the region of Ladakh lies to the north and the Kalpa valley lies to the southeast. Geologically and archaeologically, Spiti is a living museum. The mountains are devoid of any vegetation and erosion by wind, sun and snow over thousands of years has laid bare the rocks. The rugged and rocky mountain slopes sweep down to the riverbeds giving the landscape a moon-like appearance. From Chandigarh, we go via Shimla and Rampur to Kaza- headquarters of Spiti. From here we head out to Kibber, and then into the back-of-the beyond wilder parts of the Spitian Himalayas where we track Snow Leopards. -

1 Negi R, Baig S, Chandra A, Verma PK, Naithani HB, Verma R & Kumar A. Checklist of Family Poaceae in Lahaul and Spiti Distr

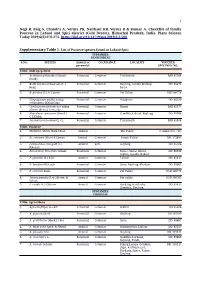

1 Negi R, Baig S, Chandra A, Verma PK, Naithani HB, Verma R & Kumar A. Checklist of family Poaceae in Lahaul and Spiti district (Cold Desert), Himachal Pradesh, India. Plant Science Today 2019;6(2):270-274. https://doi.org/10.14719/pst.2019.6.2.500 Supplementary Table 1. List of Poaceae species found in Lahaul-Spiti SUBFAMILY: PANICOIDEAE S.No. SPECIES Annual or OCCURANCE LOCALITY VOUCHER perennial SPECIMEN NO. Tribe- Andropogoneae 1. Arthraxon prionodes (Steud.) Perennial Common Trilokinath BSD 45386 Dandy 2. Bothriochloa ischaemum (L.) Perennial Common Keylong, Gondla, Kailing- DD 85472 Keng ka-Jot 3. B. pertusa (L.) A. Camus Perennial Common Pin Valley BSD100754 4. Chrysopogon gryllus subsp. Perennial Common Madgram DD 85320 echinulatus (Nees) Cope 5. Cymbopogon jwarancusa subsp. Perennial Common Kamri BSD 45377 olivieri (Boiss.) Soenarko 6. Phacelurus speciosus (Steud.) Perennial Common Gondhla, Lahaul, Keylong DD 99908 C.E.Hubb. 7. Saccharum ravennae (L.) L. Perennial Common Trilokinath BSD 45958 Tribe- Paniceae 1. Digitaria ciliaris (Retz.) Koel Annual - Pin Valley C. Sekar (loc. cit.) 2. D. cruciata (Nees) A.Camus Annual Common Pattan Valley DD 172693 3. Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) Annual Rare Keylong DD 85186 P.Beauv. 4. Pennisetum flaccidum Griseb. Perennial Common Sissoo, Sanao, Khote, DD 85530 Gojina, Gondla, Koksar 5. P. glaucum (L.) R.Br. Annual Common Lahaul DD 85417 6. P. lanatum Klotzsch Perennial Common Sissu, Keylong, Khoksar DD 99862 7. P. orientale Rich. Perennial Common Pin Valley BSD 100775 8. Setaria pumila (Poir.) Roem. & Annual Common Pin valley BSD 100763 Schult. 9. S. viridis (L.) P.Beauv. Annual Common Kardang, Baralacha, DD 85415 Gondhla, Keylong SUBFAMILY: POOIDEAE Tribe- Agrostideae 1. -

Himalayan Aromatic Medicinal Plants: a Review of Their Ethnopharmacology, Volatile Phytochemistry, and Biological Activities

medicines Review Himalayan Aromatic Medicinal Plants: A Review of their Ethnopharmacology, Volatile Phytochemistry, and Biological Activities Rakesh K. Joshi 1, Prabodh Satyal 2 and Wiliam N. Setzer 2,* 1 Department of Education, Government of Uttrakhand, Nainital 263001, India; [email protected] 2 Department of Chemistry, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, AL 35899, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-256-824-6519; Fax: +1-256-824-6349 Academic Editor: Lutfun Nahar Received: 24 December 2015; Accepted: 3 February 2016; Published: 19 February 2016 Abstract: Aromatic plants have played key roles in the lives of tribal peoples living in the Himalaya by providing products for both food and medicine. This review presents a summary of aromatic medicinal plants from the Indian Himalaya, Nepal, and Bhutan, focusing on plant species for which volatile compositions have been described. The review summarizes 116 aromatic plant species distributed over 26 families. Keywords: Jammu and Kashmir; Himachal Pradesh; Uttarakhand; Nepal; Sikkim; Bhutan; essential oils 1. Introduction The Himalya Center of Plant Diversity [1] is a narrow band of biodiversity lying on the southern margin of the Himalayas, the world’s highest mountain range with elevations exceeding 8000 m. The plant diversity of this region is defined by the monsoonal rains, up to 10,000 mm rainfall, concentrated in the summer, altitudinal zonation, consisting of tropical lowland rainforests, 100–1200 m asl, up to alpine meadows, 4800–5500 m asl. Hara and co-workers have estimated there to be around 6000 species of higher plants in Nepal, including 303 species endemic to Nepal and 1957 species restricted to the Himalayan range [2–4]. -

High Altitude Survival

High altitude survival Conflicts between pastoralism andwildlif e in the Trans-Himalaya Charudutt Mishra CENTRALE LANDBOUWCATALOGUS 0000 0873 6775 Promotor Prof.Dr .H .H .T .Prin s Hoogleraar inhe tNatuurbehee r ind eTrope n enEcologi eva n Vertebraten Co-promotor : Dr.S .E .Va nWiere n Universitair Docent, Leerstoelgroep Natuurbeheer in de Tropen enEcologi eva nVertebrate n Promotie Prof.Dr .Ir .A .J .Va n DerZijp p commissie Wageningen Universiteit Prof.Dr .J .H . Koeman Wageningen Universiteit Prof.Dr . J.P .Bakke r Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Prof.Dr .A .K .Skidmor e International Institute forAerospac e Survey and Earth Sciences, Enschede High altitude survival: conflicts between pastoralism and wildlife inth e Trans-Himalaya Charudutt Mishra Proefschrift ter verkrijging van degraa d van doctor opgeza g van derecto r magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit prof. dr. ir. L. Speelman, inhe t openbaar te verdedigen opvrijda g 14decembe r200 1 des namiddags te 13:30uu r in deAul a -\ •> Mishra, C. High altitude survival:conflict s between pastoralism andwildlif e inth e Trans-Himalaya Wageningen University, The Netherlands. Doctoral Thesis (2001); ISBN 90-5808-542-2 A^ofZC , "SMO Propositions 1. Classical nature conservation measures will not suffice, because the new and additional measures that have to be taken must be especially designed for those areas where people live and use resources (Herbert Prins, The Malawi principles: clarification of thoughts that underlaythe ecosystem approach). 2. The ability tomak e informed decisions on conservation policy remains handicapped due to poor understanding of the way people use natural resources, and the impacts of such resource use onwildlif e (This thesis). -

Himachal Pradesh in the Indian Himalaya

Mountain Livelihoods in Transition: Constraints and Opportunities in Kinnaur, Western Himalaya By Aghaghia Rahimzadeh A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy and Management in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Louise P. Fortmann, Chair Professor Nancy Lee Peluso Professor Isha Ray Professor Carolyn Finney Spring 2016 Mountain Livelihoods in Transition: Constraints and Opportunities in Kinnaur, Western Himalaya Copyright © 2016 By Aghaghia Rahimzadeh Abstract Mountain Livelihoods in Transition: Constraints and Opportunities in Kinnaur, Western Himalaya by Aghaghia Rahimzadeh Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy and Management University of California, Berkeley Professor Louise P. Fortmann, Chair This dissertation investigates the transformation of the district of Kinnaur in the state of Himachal Pradesh in the Indian Himalaya. I examine Kinnauri adaptation to political, economic, environmental, and social events of the last seven decades, including state intervention, market integration, and climate change. Broadly, I examine drivers of change in Kinnaur, and the implications of these changes on social, cultural, political, and environmental dynamics of the district. Based on findings from 11 months of ethnographic field work, I argue that Kinnaur’s transformation and current economic prosperity have been chiefly induced by outside forces, creating a temporary landscape of opportunity. State-led interventions including land reform and a push to supplement subsistence agriculture with commercial horticulture initiated a significant agrarian transition beginning with India’s Independence. I provide detailed examination of the Nautor Land Rules of 1968 and the 1972 Himachel Pradesh Ceiling of Land Holding Act, and their repercussion on land allocation to landless Kinnauris. -

The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past & Exploring the Present OXFORD

The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past & Exploring the Present Wolfson College 6 t h -7 t h May, 2016 OXFORD Welcome I am pleased to welcome you to the first International Conference on Spiti, which is being held at the Leonard Wolfson Auditorium on May 6 th and 7 th , 2016. The Spiti Valley is a remote Buddhist enclave in the Indian Himalayas. It is situated on the borders of the Tibetan world with which it shares strong cultural and historical ties. Often under-represented on both domestic and international levels, scholarly research on this subject – all disciplines taken together – has significantly increased over the past decade. The conference aims at bringing together researchers currently engaged in a dialogue with past and present issues pertaining to Spitian culture and society in all its aspects. It is designed to encourage interdisciplinary exchanges in order to explore new avenues and pave the way for future research. There are seven different panels that address the theme of this year’s conference, The Spiti Valley : Recovering the Past and Exploring the Present , from a variety of different disciplinary perspectives including, archaeology, history, linguistics, anthropology, architecture, and art conservation. I look forward to the exchange of ideas and intellectual debates that will develop over these two days. On this year’s edition, we are very pleased to have Professor Deborah Klimburg-Salter from the universities of Vienna and Harvard as our keynote speaker. Professor Klimburg-Salter will give us a keynote lecture entitled Through the black light - new technology opens a window on the 10th century . -

Lahaul, Spiti & Kinnaur Substate BSAP

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY SUB- STATE SITE BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN (LAHAUL & SPITI AND KINNAUR) MAY-2002 SUBMITTED TO: TPCG (NBSAP), MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT & FOREST,GOI, NEW DELHI, TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT, H.P. SECRETARIAT, SHIMLA-2 & STATE COUNCIL FOR SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT, 34 SDA COMPLEX, KASUMPTI, SHIMLA –9 CONTENTS S. No. Chapter Pages 1. Introduction 1-6 2. Profile of Area 7-16 3. Current Range and Status of Biodiversity 17-35 4. Statement of the problems relating to 36-38 biodiversity 5. Major Actors and their current roles relevant 39-40 to biodiversity 6. Ongoing biodiversity- related initiatives 41-46 (including assessment of their efficacy) 7. Gap Analysis 47-48 8. Major strategies to fill these gaps and to 49-51 enhance/strengthen ongoing measures 9. Required actions to fill gaps, and 52-61 enhance/strengthen ongoing measures 10. Proposed Projects for Implementation of 62-74 Action Plan 11. Comprehensive Note 75-81 12. Public Hearing 82-86 13. Synthesis of the Issues/problems 87-96 14. Bibliography 97-99 Annexures CHAPTER- 1 INTRODUCTION Biodiversity or Biological Diversity is the variability within and between all microorganisms, plants and animals and the ecological system, which they inhabit. It starts with genes and manifests itself as organisms, populations, species and communities, which give life to ecosystems, landscapes and ultimately the biosphere (Swaminathan, 1997). India in general and Himalayas in particular are the reservoir of genetic wealth ranging from tropical, sub-tropical, sub temperate including dry temperate and cold desert culminating into alpine (both dry and moist) flora and fauna. -

Himalayan and Central Asian Studies

ISSN 0971-9318 HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES (JOURNAL OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH AND CULTURAL FOUNDATION) NGO in Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC, United Nations Vol. 17 No. 3-4 July-December 2013 Political change in China and the new 5th Generation Leadership Michael Dillon Financial Diplomacy: The Internationalization of the Chinese Yuan Ivanka Petkova Understanding China’s Policy and Intentions towards the SCO Michael Fredholm Cyber Warfare: China’s Role and Challenge to the United States Arun Warikoo India and China: Contemporary Issues and Challenges B.R. Deepak The Depsang Standoff at the India-China Border along the LAC: View from Ladakh Deldan Kunzes Angmo Nyachu China- Myanmar: No More Pauk Phaws? Rahul Mishra Pakistan-China Relations: A Case Study of All-Weather Friendship Ashish Shukla Afghanistan-China Relations: 1955-2012 Mohammad Mansoor Ehsan HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES Guest Editor : MONDIRA DUTTA © Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation, New Delhi. * All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without first seeking the written permission of the publisher or due acknowledgement. * The views expressed in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or policies of the Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation. SUBSCRIPTION IN INDIA Single Copy (Individual) : Rs. 500.00 Annual (Individual) : Rs. 1000.00 Institutions : Rs. 1400.00 & Libraries (Annual) -

Diversity of Herbs in Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary of Distt. Lahaul and Spiti

Biological Forum – An International Journal 12(2): 01-12(2020) ISSN No. (Print): 0975-1130 ISSN No. (Online): 2249-3239 Diversity of Herbs in Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary of Distt. Lahaul and Spiti, Himachal Pradesh Ranjeet Kumar, Raj Kumar Verma, Suraj Kumar, Chaman Thakur, Rajender Prakash, Krishna Kumari, Dushyant and Saurabh Yadav Himalayan Forest Research Institute, Panthaghati, Shimla (Himachal Pradesh), India. (Corresponding author: Ranjeet Kumar) (Received 09 June 2020, Accepted 29 July, 2020) (Published by Research Trend, Website: www.researchtrend.net) ABSTRACT: The cold desert in Himalayas are home of unique and threatened plants. The landscapes of cold deserts are rich in biodiversity due to unique topography, climatic conditions and variation in plant diversity in different habitats. The plant diversity provides information on plant wealth of particular area. The present investigation was conducted to know the phytodiversity of herbs in Kibber Beat of Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary (KWLS) during 2017-2019. The study included dominance of vegetation, diversity indices and documentation of threatened plants. Total 12 communities, 22 family, 50 genera and 71 species were recorded during the study in Kibber Beat of the Sanctuary. Total 4 numbers of threatened plants were recorded viz., Arnebia euchroma, Berginia stracheyi, Physochlaena praealta and Rhodiola heterodonta. Total density/m2 of herbs varied from 7.35 to 54.85. Maximum value of diversity index (H) in communities was 2.84 and minimum was 1.81. Ex-situ conservation of plants is required to conserve the diversity of plants of the cold desert. Keywords: Cold desert, Kibber, herbs, community and phytosociology. I. INTRODUCTION wild annual and perennial herbs followed by dwarf bushes or shrubs (Saxena et al., 2018). -

History : Project Deepak

HISTORY : PROJECT DEEPAK 1. Raising & Early History. Project Deepak was raised in May 1961 with Col S N Punjh as Chief Engineer, primarily for the construction of Hindustan-Tibet (H-T) Road. The H-T Road is one of the most difficult roads ever to have been constructed in India. The 76 Km long Pooh-Kaurik sector of H-T Road passes through considerable lengths of sheer vertical hard rock stretches and huge bouldery strata embedded in sand and non-cohesive material, which is inherently unstable. The sector runs along the River Satluj crossing it at several locations. The road runs at altitudes between 1600 to 3600 meters. On the whole, the terrain and climatic conditions are very uncongenial. Many valuable lives were lost during the construction of this road. Thus, this work is a testimony to the sheer grit, determination and perseverance shown by PROJECT DEEPAK right from its early days. The subsequent major events in the history of Project Deepak include:- (a) In 1965, construction of the 122 Km long Road Dhami-Basantpur-Kiongal and 107 Km long stretch of Road Keylong-Sarchu (part of the Manali-Leh road) was entrusted to PROJECT DEEPAK. (b) In December 1966, following disbandment of Project Chetak, all roads of Uttaranchal were taken over by PROJECT DEEPAK. Thus, the 300 Km long Road Rishikesh –Joshimath-Mana, 63 Km long road Road Joshimath-Malari and 260 Km long Road Tanakpur-Askote-Tawaghat came under PROJECT DEEPAK. (c) The early seventies saw Project Deepak spreading its light (Deepak Jyoti) in the states of Rajasthan and even Punjab. -

Border Area Development Programme

BORDER AREA DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME HIMACHAL PRADESH Introduction: 1. In view of persistent demands and considering the overall situation in the border areas of Himachal Pradesh, the Planning Commission, Govt. of India decided to extend Border Area Development Programme to Himachal Pradesh for the three blocks viz. Kalpa and Pooh Blocks of Kinnaur District and Spiti Block of Lahaul- Spiti Districts having borders with China from 1998-99. The basic objective of the scheme is to meet the special needs of the people living in remote, inaccessible areas situated near the border. The emphasis is to be laid on schemes for employment promotion, production oriented activities and schemes which provide critical inputs to the social sectors. As per guidelines, the funds under Special Central Assistance has been made available to border blocks of the State considering the length of the border area and population of the bordering blocks. The Planning Commission Govt. of India and Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India has provided Rs. 3547.00 lakh during the period of 9th Five Year Plan beginning from 1998-99 to 2001-02 and Rs.4573.86 lakh during 10th Five Year Plan 2002-2007 as Special Central Assistance under this programme. An outlay of Rs. 18675.62 lakh is proposed for comprehensive development plan for Himachal Pradesh during 11th Five Year Plan 2007-12 under Border Area Development Programme for these three Blocks. Out of above proposed outlays, Rs. 1119.00 lakh is being utilized during current financial year 2007-08 for various infrastructural developments relevant to these border blocks.