Centrosome Function and Assembly in Animal Cells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Extensive Program of Periodic Alternative Splicing Linked to Cell

RESEARCH ARTICLE An extensive program of periodic alternative splicing linked to cell cycle progression Daniel Dominguez1,2, Yi-Hsuan Tsai1,3, Robert Weatheritt4, Yang Wang1,2, Benjamin J Blencowe4*, Zefeng Wang1,5* 1Department of Pharmacology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, United States; 2Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, United States; 3Program in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, United States; 4Donnelly Centre and Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; 5Key Lab of Computational Biology, CAS-MPG Partner Institute for Computational Biology, Chinese Academy of Science, Shanghai, China Abstract Progression through the mitotic cell cycle requires periodic regulation of gene function at the levels of transcription, translation, protein-protein interactions, post-translational modification and degradation. However, the role of alternative splicing (AS) in the temporal control of cell cycle is not well understood. By sequencing the human transcriptome through two continuous cell cycles, we identify ~ 1300 genes with cell cycle-dependent AS changes. These genes are significantly enriched in functions linked to cell cycle control, yet they do not significantly overlap genes subject to periodic changes in steady-state transcript levels. Many of the periodically spliced genes are controlled by the SR protein kinase CLK1, whose level undergoes cell cycle- dependent fluctuations via an auto-inhibitory circuit. Disruption of CLK1 causes pleiotropic cell cycle defects and loss of proliferation, whereas CLK1 over-expression is associated with various *For correspondence: cancers. These results thus reveal a large program of CLK1-regulated periodic AS intimately [email protected] (BJB); associated with cell cycle control. -

Centrosome Positioning in Vertebrate Development

Commentary 4951 Centrosome positioning in vertebrate development Nan Tang1,2,*,` and Wallace F. Marshall2,` 1Department of Anatomy, Cardiovascular Research Institute, The University of California, San Francisco, USA 2Department Biochemistry and Biophysics, The University of California, San Francisco, USA *Present address: National Institute of Biological Science, Beijing, China `Authors for correspondence ([email protected]; [email protected]) Journal of Cell Science 125, 4951–4961 ß 2012. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd doi: 10.1242/jcs.038083 Summary The centrosome, a major organizer of microtubules, has important functions in regulating cell shape, polarity, cilia formation and intracellular transport as well as the position of cellular structures, including the mitotic spindle. By means of these activities, centrosomes have important roles during animal development by regulating polarized cell behaviors, such as cell migration or neurite outgrowth, as well as mitotic spindle orientation. In recent years, the pace of discovery regarding the structure and composition of centrosomes has continuously accelerated. At the same time, functional studies have revealed the importance of centrosomes in controlling both morphogenesis and cell fate decision during tissue and organ development. Here, we review examples of centrosome and centriole positioning with a particular emphasis on vertebrate developmental systems, and discuss the roles of centrosome positioning, the cues that determine positioning and the mechanisms by which centrosomes respond to these cues. The studies reviewed here suggest that centrosome functions extend to the development of tissues and organs in vertebrates. Key words: Centrosome, Development, Mitotic spindle orientation Introduction radiating out to the cell cortex (Fig. 2A). In some cases, the The centrosome of animal cells (Fig. -

Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly Primary Hereditary: an Overview

brain sciences Review Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly Primary Hereditary: An Overview Nikistratos Siskos † , Electra Stylianopoulou †, Georgios Skavdis and Maria E. Grigoriou * Department of Molecular Biology & Genetics, Democritus University of Thrace, 68100 Alexandroupolis, Greece; [email protected] (N.S.); [email protected] (E.S.); [email protected] (G.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] † Equal contribution. Abstract: MicroCephaly Primary Hereditary (MCPH) is a rare congenital neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a significant reduction of the occipitofrontal head circumference and mild to moderate mental disability. Patients have small brains, though with overall normal architecture; therefore, studying MCPH can reveal not only the pathological mechanisms leading to this condition, but also the mechanisms operating during normal development. MCPH is genetically heterogeneous, with 27 genes listed so far in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database. In this review, we discuss the role of MCPH proteins and delineate the molecular mechanisms and common pathways in which they participate. Keywords: microcephaly; MCPH; MCPH1–MCPH27; molecular genetics; cell cycle 1. Introduction Citation: Siskos, N.; Stylianopoulou, Microcephaly, from the Greek word µικρoκεϕαλi´α (mikrokephalia), meaning small E.; Skavdis, G.; Grigoriou, M.E. head, is a term used to describe a cranium with reduction of the occipitofrontal head circum- Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly ference equal, or more that teo standard deviations -

Ninein, a Microtubule Minus-End Anchoring Protein 3015 Analysis As Described Previously (Henderson Et Al., 1994)

Journal of Cell Science 113, 3013-3023 (2000) 3013 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 2000 JCS1634 Microtubule minus-end anchorage at centrosomal and non-centrosomal sites: the role of ninein Mette M. Mogensen1,*, Azer Malik1, Matthieu Piel2, Veronique Bouckson-Castaing2 and Michel Bornens2 1Department of Anatomy and Physiology, MSI/WTB complex, Dow Street, University of Dundee, Dundee, DD1 5EH, UK 2Institute Curie, UMR 144-CNRS, 26 Rue d’Ulm, 75248 Paris Cedex 05, France *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 14 June; published on WWW 9 August 2000 SUMMARY The novel concept of a centrosomal anchoring complex, epithelial cells, where the vast majority of the microtubule which is distinct from the γ-tubulin nucleating complex, has minus-ends are associated with apical non-centrosomal previously been proposed following studies on cochlear sites, suggests that it is not directly involved in microtubule epithelial cells. In this investigation we present evidence nucleation. Ninein seems to play an important role in the from two different cell systems which suggests that the positioning and anchorage of the microtubule minus-ends centrosomal protein ninein is a strong candidate for the in these epithelial cells. Evidence is presented which proposed anchoring complex. suggests that ninein is released from the centrosome, Ninein has recently been observed in cultured fibroblast translocated with the microtubules, and is responsible for cells to localise primarily to the post-mitotic mother the anchorage of microtubule minus-ends to the apical centriole, which is the focus for a classic radial microtubule sites. We propose that ninein is a non-nucleating array. -

Centrosome Impairment Causes DNA Replication Stress Through MLK3

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.09.898684; this version posted January 10, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Centrosome impairment causes DNA replication stress through MLK3/MK2 signaling and R-loop formation Zainab Tayeh 1, Kim Stegmann 1, Antonia Kleeberg 1, Mascha Friedrich 1, Josephine Ann Mun Yee Choo 1, Bernd Wollnik 2, and Matthias Dobbelstein 1* 1) Institute of Molecular Oncology, Göttingen Center of Molecular Biosciences (GZMB), University Medical Center Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany 2) Institute of Human Genetics, University Medical Center Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany *Lead Contact. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M. D. (e-mail: [email protected]; ORCID 0000-0001-5052-3967) Running title: Centrosome integrity supports DNA replication Key words: Centrosome, CEP152, CCP110, SASS6, CEP152, Polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4), DNA replication, DNA fiber assays, R-loops, MLK3, MK2 alias MAPKAPK2, Seckel syndrome, microcephaly. Highlights: • Centrosome defects cause replication stress independent of mitosis. • MLK3, p38 and MK2 (alias MAPKAPK2) are signalling between centrosome defects and DNA replication stress through R-loop formation. • Patient-derived cells with defective centrosomes display replication stress, whereas inhibition of MK2 restores their DNA replication fork progression and proliferation. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.09.898684; this version posted January 10, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

S41467-019-10037-Y.Pdf

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10037-y OPEN Feedback inhibition of cAMP effector signaling by a chaperone-assisted ubiquitin system Laura Rinaldi1, Rossella Delle Donne1, Bruno Catalanotti 2, Omar Torres-Quesada3, Florian Enzler3, Federica Moraca 4, Robert Nisticò5, Francesco Chiuso1, Sonia Piccinin5, Verena Bachmann3, Herbert H Lindner6, Corrado Garbi1, Antonella Scorziello7, Nicola Antonino Russo8, Matthis Synofzik9, Ulrich Stelzl 10, Lucio Annunziato11, Eduard Stefan 3 & Antonio Feliciello1 1234567890():,; Activation of G-protein coupled receptors elevates cAMP levels promoting dissociation of protein kinase A (PKA) holoenzymes and release of catalytic subunits (PKAc). This results in PKAc-mediated phosphorylation of compartmentalized substrates that control central aspects of cell physiology. The mechanism of PKAc activation and signaling have been largely characterized. However, the modes of PKAc inactivation by regulated proteolysis were unknown. Here, we identify a regulatory mechanism that precisely tunes PKAc stability and downstream signaling. Following agonist stimulation, the recruitment of the chaperone- bound E3 ligase CHIP promotes ubiquitylation and proteolysis of PKAc, thus attenuating cAMP signaling. Genetic inactivation of CHIP or pharmacological inhibition of HSP70 enhances PKAc signaling and sustains hippocampal long-term potentiation. Interestingly, primary fibroblasts from autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia 16 (SCAR16) patients carrying germline inactivating mutations of CHIP show a dramatic dysregulation of PKA signaling. This suggests the existence of a negative feedback mechanism for restricting hormonally controlled PKA activities. 1 Department of Molecular Medicine and Medical Biotechnologies, University Federico II, 80131 Naples, Italy. 2 Department of Pharmacy, University Federico II, 80131 Naples, Italy. 3 Institute of Biochemistry and Center for Molecular Biosciences, University of Innsbruck, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria. -

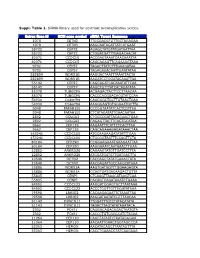

Suppl. Table 1

Suppl. Table 1. SiRNA library used for centriole overduplication screen. Entrez Gene Id NCBI gene symbol siRNA Target Sequence 1070 CETN3 TTGCGACGTGTTGCTAGAGAA 1070 CETN3 AAGCAATAGATTATCATGAAT 55722 CEP72 AGAGCTATGTATGATAATTAA 55722 CEP72 CTGGATGATTTGAGACAACAT 80071 CCDC15 ACCGAGTAAATCAACAAATTA 80071 CCDC15 CAGCAGAGTTCAGAAAGTAAA 9702 CEP57 TAGACTTATCTTTGAAGATAA 9702 CEP57 TAGAGAAACAATTGAATATAA 282809 WDR51B AAGGACTAATTTAAATTACTA 282809 WDR51B AAGATCCTGGATACAAATTAA 55142 CEP27 CAGCAGATCACAAATATTCAA 55142 CEP27 AAGCTGTTTATCACAGATATA 85378 TUBGCP6 ACGAGACTACTTCCTTAACAA 85378 TUBGCP6 CACCCACGGACACGTATCCAA 54930 C14orf94 CAGCGGCTGCTTGTAACTGAA 54930 C14orf94 AAGGGAGTGTGGAAATGCTTA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CCCGGTAATATCACTCGTTAA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CTCATAGATATTGAACAATAA 2802 GOLGA3 CTGGCCGATTACAGAACTGAA 2802 GOLGA3 CAGAGTTACTTCAGTGCATAA 9662 CEP135 AAGAATTTCATTCTCACTTAA 9662 CEP135 CAGCAGAAAGAGATAAACTAA 153241 CCDC100 ATGCAAGAAGATATATTTGAA 153241 CCDC100 CTGCGGTAATTTCCAGTTCTA 80184 CEP290 CCGGAAGAAATGAAGAATTAA 80184 CEP290 AAGGAAATCAATAAACTTGAA 22852 ANKRD26 CAGAAGTATGTTGATCCTTTA 22852 ANKRD26 ATGGATGATGTTGATGACTTA 10540 DCTN2 CACCAGCTATATGAAACTATA 10540 DCTN2 AACGAGATTGCCAAGCATAAA 25886 WDR51A AAGTGATGGTTTGGAAGAGTA 25886 WDR51A CCAGTGATGACAAGACTGTTA 55835 CENPJ CTCAAGTTAAACATAAGTCAA 55835 CENPJ CACAGTCAGATAAATCTGAAA 84902 CCDC123 AAGGATGGAGTGCTTAATAAA 84902 CCDC123 ACCCTGGTTGTTGGATATAAA 79598 LRRIQ2 CACAAGAGAATTCTAAATTAA 79598 LRRIQ2 AAGGATAATATCGTTTAACAA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TTGGATTTGTCTATACATATA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TAGACTTAGTATATAAATACA 2302 FOXJ1 CAGGACAGACAGACTAATGTA -

RACK1 Regulates Centriole Duplication Through Promoting the Activation Of

© 2020. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2020) 133, jcs238931. doi:10.1242/jcs.238931 RESEARCH ARTICLE RACK1 regulates centriole duplication through promoting the activation of polo-like kinase 1 by Aurora A Yuki Yoshino1,2,3,*, Akihiro Kobayashi1,2,*, Huicheng Qi1,2, Shino Endo1,2, Zhenzhou Fang1,2, Kazuha Shindo1,3, Ryo Kanazawa1,3 and Natsuko Chiba1,2,3,‡ ABSTRACT Centrosomes consist of a pair of centrioles, termed the mother Breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) contributes to the regulation of centriole and the daughter centriole, and proteinaceous centrosome number. We previously identified receptor for activated C pericentriolar material surrounding the mother centriole (Conduit kinase 1 (RACK1) as a BRCA1-interacting partner. RACK1, a scaffold et al., 2015). The proper number of centrosomes is stably protein that interacts with multiple proteins through its seven WD40 maintained by a regulatory network that ensures duplication only domains, directly binds to BRCA1 and localizes to centrosomes. once per cell cycle (Conduit et al., 2015; Fujita et al., 2016; Nigg RACK1 knockdown suppresses centriole duplication, whereas and Holland, 2018). At entry into mitosis, a cell has two RACK1 overexpression causes centriole overduplication in a subset centrosomes, each containing a pair of tightly engaged centrioles. of mammary gland-derived cells. In this study, we showed that During mitosis, centrioles lose their connection in a process termed RACK1 binds directly to polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) and Aurora A, and disengagement, and the two centrioles are joined by a flexible promotes the Aurora A–PLK1 interaction. RACK1 knockdown linker. In late G1 phase of the following cell cycle, a new daughter decreased phosphorylated PLK1 (p-PLK1) levels and the centrosomal centriole is generated on the side wall of each mother centriole. -

Association of Cnvs with Methylation Variation

www.nature.com/npjgenmed ARTICLE OPEN Association of CNVs with methylation variation Xinghua Shi1,8, Saranya Radhakrishnan2, Jia Wen1, Jin Yun Chen2, Junjie Chen1,8, Brianna Ashlyn Lam1, Ryan E. Mills 3, ✉ ✉ Barbara E. Stranger4, Charles Lee5,6,7 and Sunita R. Setlur 2 Germline copy number variants (CNVs) and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) form the basis of inter-individual genetic variation. Although the phenotypic effects of SNPs have been extensively investigated, the effects of CNVs is relatively less understood. To better characterize mechanisms by which CNVs affect cellular phenotype, we tested their association with variable CpG methylation in a genome-wide manner. Using paired CNV and methylation data from the 1000 genomes and HapMap projects, we identified genome-wide associations by methylation quantitative trait locus (mQTL) analysis. We found individual CNVs being associated with methylation of multiple CpGs and vice versa. CNV-associated methylation changes were correlated with gene expression. CNV-mQTLs were enriched for regulatory regions, transcription factor-binding sites (TFBSs), and were involved in long- range physical interactions with associated CpGs. Some CNV-mQTLs were associated with methylation of imprinted genes. Several CNV-mQTLs and/or associated genes were among those previously reported by genome-wide association studies (GWASs). We demonstrate that germline CNVs in the genome are associated with CpG methylation. Our findings suggest that structural variation together with methylation may affect cellular phenotype. npj Genomic Medicine (2020) 5:41 ; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-020-00145-w 1234567890():,; INTRODUCTION influence transcript regulation is DNA methylation, which involves The extent of genetic variation that exists in the human addition of a methyl group to cytosine residues within a CpG population is continually being characterized in efforts to identify dinucleotide. -

Pericentrin Polyclonal Antibody Catalog Number:22271-1-AP 1 Publications

For Research Use Only Pericentrin Polyclonal antibody Catalog Number:22271-1-AP 1 Publications www.ptglab.com Catalog Number: GenBank Accession Number: Purification Method: Basic Information 22271-1-AP NM_006031 Antigen affinity purification Size: GeneID (NCBI): Recommended Dilutions: 150UL , Concentration: 800 μg/ml by 5116 IF 1:50-1:500 Nanodrop and 360 μg/ml by Bradford Full Name: method using BSA as the standard; pericentrin Source: Calculated MW: Rabbit 378 kDa Isotype: IgG Applications Tested Applications: Positive Controls: IF,ELISA IF : MDCK cells, Cited Applications: IF Species Specificity: human, Canine Cited Species: human PCNT, also named as KIAA0402, PCNT2, Pericentrin-B and Kendrin, is an integral component of the filamentous Background Information matrix of the centrosome involved in the initial establishment of organized microtubule arrays in both mitosis and meiosis. PCNT plays a role, together with DISC1, in the microtubule network formation. Is an integral component of the pericentriolar material (PCM). PCNT is a marker of centrosome. Defects in PCNT are the cause of microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism type 2 (MOPD2). The antibody is specific to PCNT, and it can recognize isoform 1 and 2. Notable Publications Author Pubmed ID Journal Application Won-Jing Wang 26609813 Elife IF Storage: Storage Store at -20°C. Stable for one year after shipment. Storage Buffer: PBS with 0.02% sodium azide and 50% glycerol pH 7.3. Aliquoting is unnecessary for -20ºC storage For technical support and original validation data for this product please contact: This product is exclusively available under Proteintech T: 1 (888) 4PTGLAB (1-888-478-4522) (toll free E: [email protected] Group brand and is not available to purchase from any in USA), or 1(312) 455-8498 (outside USA) W: ptglab.com other manufacturer. -

An Exome-Wide Sequencing Study of Lipid Response to High-Fat Meal and Fenofibrate in Caucasians from the GOLDN Cohort

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2018 An exome-wide sequencing study of lipid response to high-fat meal and fenofibrate in Caucasians from the GOLDN cohort Xin Geng Ping An Mary F. Feitosa Michael A. Province et al. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Supplemental Material can be found at: http://www.jlr.org/content/suppl/2018/02/20/jlr.P080333.DC1 .html patient-oriented and epidemiological research An exome-wide sequencing study of lipid response to high-fat meal and fenofibrate in Caucasians from the GOLDN cohort Xin Geng,* Marguerite R. Irvin,† Bertha Hidalgo,† Stella Aslibekyan,† Vinodh Srinivasasainagendra,§ Ping An,‡ Alexis C. Frazier-Wood,|| Hemant K. Tiwari,§ Tushar Dave,# Kathleen Ryan,# Jose M. Ordovas,$,**,†† Robert J. Straka,§§ Mary F. Feitosa,‡ Paul N. Hopkins,‡‡ Ingrid Borecki,|| || Michael A. Province,‡ Braxton D. Mitchell,# Donna K. Arnett,1,## and Degui Zhi1,*,$$ School of Biomedical Informatics* and School of Public Health,$$ The University of Texas Health Downloaded from Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030; Departments of Epidemiology† and Biostatistics,§ University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35233; Division of Statistical Genomics, Department of Genetics,‡ Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110; US Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service Children’s Nutrition Research Center,|| Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030; Department of Medicine, Division -

PCM1 Recruits Plk1 to the Pericentriolar Matrix to Promote

Research Article 1355 PCM1 recruits Plk1 to the pericentriolar matrix to promote primary cilia disassembly before mitotic entry Gang Wang1,*, Qiang Chen1,*, Xiaoyan Zhang1, Boyan Zhang1, Xiaolong Zhuo1, Junjun Liu2, Qing Jiang1 and Chuanmao Zhang1,` 1MOE Key Laboratory of Cell Proliferation and Differentiation and State Key Laboratory of Biomembrane and Membrane Biotechnology, College of Life Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 2Department of Biological Sciences, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA 91768, USA *These authors contributed equally to this work `Author for correspondence ([email protected]) Accepted 11 December 2012 Journal of Cell Science 126, 1355–1365 ß 2013. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd doi: 10.1242/jcs.114918 Summary Primary cilia, which emanate from the cell surface, exhibit assembly and disassembly dynamics along the progression of the cell cycle. However, the mechanism that links ciliary dynamics and cell cycle regulation remains elusive. In the present study, we report that Polo- like kinase 1 (Plk1), one of the key cell cycle regulators, which regulate centrosome maturation, bipolar spindle assembly and cytokinesis, acts as a pivotal player that connects ciliary dynamics and cell cycle regulation. We found that the kinase activity of centrosome enriched Plk1 is required for primary cilia disassembly before mitotic entry, wherein Plk1 interacts with and activates histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) to promote ciliary deacetylation and resorption. Furthermore, we showed that pericentriolar material 1 (PCM1) acts upstream of Plk1 and recruits the kinase to pericentriolar matrix (PCM) in a dynein-dynactin complex-dependent manner. This process coincides with the primary cilia disassembly dynamics at the onset of mitosis, as depletion of PCM1 by shRNA dramatically disrupted the pericentriolar accumulation of Plk1.