Assessment of Genetic Relationship Between Six Populations of Welsh Mountain Sheep Using Microsatellite Markers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March Newsletter 2015 Final Version 3

Official Society Newsletter Ryeland Fbs Incorporating Coloured Ryeland News Spring 2015 Ryeland Lamb 2015 Ryeland Fbs Contact - Dot Tyne, Secretary, Ty’n y Mynydd Farm, Boduan, Pwllheli, Gwynedd, LL53 8PZ Telephone - 01758 721739 Email - [email protected] Opinions expressed by authors and services offered by advertisers are not specifically endorsed by the Ryeland Fbs. Advertisers must warrant that copy does not contravene, the Trades Description Act 1968. Sex Discrimination Act 1975 or The Business Advertisements (Disclosure) Order 1977 Newsletter Printed by SJH Print From The Editor Well first of all may I say a HAPPY NEW YEAR to you all. I hope you all enjoyed the Winter Newsletter, and found it fun and informative. Now to say Welcome to the new look newsletter, after a lot of research and proposals to council, we came up with this new design, The reason being we felt it 1 was time to bring this unique offering as a society up to date, it based on many different societies yearly newsletter, we are lucky enough to have one every quarter. In this newsletter we bring you a vast array of articles, From genetic updates, to a piece on the biggest sheep show in the UK. You will see that we have a few more changes in this newsletter, we have decided to make more of a feature of the Vets Articles making it an ‘Issue’ type article, Also we have decided to make more of a feature of the Coloured Ryeland News, with their own front cover making it the same as the overall newsletter. -

1 a Lleyn Sweep for Local Sheep? Breed Societies and the Geographies of Welsh Livestock

A Lleyn Sweep for Local Sheep? Breed Societies and the Geographies of Welsh Livestock Richard Yarwood* and Nick Evans+ * School of Geography, University of Plymouth, Drake Circus, Plymouth, PL4 8AA. [email protected] 01752 233083 + Centre for Rural Research Department of Applied Sciences, Geography and Archaeology, University College Worcester, Henwick Grove, Worcester, WR2 6AJ. 01905 855197 [email protected] Abstract This paper uses Bourdieu’s (1977) concept of habitus to examine human-animal relationships within capitalist agricultural systems. The first part of the paper examines how Bourdieu’s ideas have been used by academics to provide insights into the ways that livestock affect and are affected by farming practice. The second part builds on these conceptual, empirical and policy insights by examining some of the national and international social networks that contribute to human-animal relationships in capitalistic farming. It focuses on a case study of Welsh livestock and, in particular, the historic and contemporary roles that breed societies play in the imagination of farm animals and the creation of capitals in agriculture. 1 A Lleyn Sweep for Local Sheep? Breed Societies and the Geographies of Welsh Livestock ‘The mountain sheep are sweeter, But the valley sheep are fatter; And so we deemed it meeter To take away the latter.’ „The War-Song of the Dinas Vawr‟ Thomas Love Peacock (1829) Introduction The relationships between animals, locality and society have come under increased scrutiny by geographers (Philo, 1995; Wolch and Emel, 1995; Wolch, 1998; Philo and Wilbert, 2000). An emerging body of literature is critically reappraising the place of animals within capitalist agricultural systems, reflecting the three main trajectories of animal geography (Whatmore, 2000). -

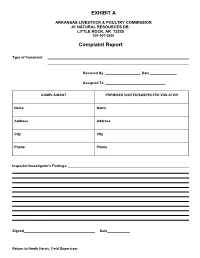

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

Your Business Your Future A4 ADVERT 11/5/17 17:55 Page 1

Sheep FarmerAUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2017 A NATIONAL SHEEP ASSOCIATION PUBLICATION PROMOTING AND SELLING LAMB – DIRECT TO THE CUSTOMER TACKLING TOXOPLASMOSIS PRIOR TO TUPPING NSA POLICY UPDATE ROTATIONAL GRAZING STRATEGIES NSA REGIONAL EVENT REPORTS AND SALE PREVIEWS BLUETONGUE AND PNEUMONIA UPDATES your business your future A4 ADVERT 11/5/17 17:55 Page 1 Deliver thr Sheep oughouty assisted UK Defra is listening – Farmer August/September but it’s still early days 2017 edition Vol. 36, No 4 ISSN 0141-2434 A National Sheep Association publication. Each one of this year’s six regional NSA sheep events has been a huge Contents success and credit must go to the 2 News round-up event organisers and their committees, the armies of volunteers that help in 4 NSA reports: devolved nations advance and on the day, and – of course 6 NSA reports: English regions – the hosts. 8 NSA ram sale previews Without sounding like British Rail, one NSA Highland Sheep report or two events suffered with the weather 11 being too wet and one, in particular, saw 12 NSA North Sheep report conditions that were too hot. But you 14 NSA Sheep SW report have to take the rough with the smooth 15 NSA Sheep Northern Ireland and at least they took place – and were report on time! 16 Win a lamb weigh crate On a serious note, these events ministers are still keen to see our 18 perform a unique function. They are welfare standards go higher, even Latest NSA activity entirely sheep related business-to- though there is little evidence that 20 FARM FEATURE: former NSA Order your rams business and technically focussed we can use this within WTO rules to Chairman John Geldard shows. -

ACE Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA August 13, 2021 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes .................................................................................................................................................... 4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes ........................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ................................................................................................... 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes .......................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers ........................................................................ 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ............................................................................................................................. 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers ........................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure ...................................................................................................................................... 30 PG05 – Scientific Species Code ........................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ........................................................................................................... -

Regulatory Appraisal

REGULATORY APPRAISAL ANIMAL HEALTH, WALES THE TRANSMISSIBLE SPONGIFORM ENCEPHALOPATHIES (WALES) REGULATIONS 2006 Purpose and intended effect of the measure 1. The intended effect of the Instrument, which applies in relation to Wales, is to revoke and remake with amendments the TSE (Wales) Regulations 2002, which enforced Regulation (EC) No. 999/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down rules for the prevention, control and eradication of certain transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. 2. In response to the introduction of the Community TSE Regulations (Regulation (EC) 999/2001) and to consolidate Welsh legislation enacted in response to the BSE epidemic in Wales and the UK, the Welsh Assembly Government enacted the TSE (Wales) Regulations in 2002. Parallel legislation was also introduced in England, Scotland and Northern Ireland. 3. Regulation (EC) No. 999/2001 provides a framework for the prevention, control and eradication of certain transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs). TSEs are diseases of the brain and nervous system that gradually destroy brain tissues, resulting in a characteristic ‘sponge-like’ appearance. Examples include scrapie in sheep, Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle and Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) in humans. The TSE (Wales) Regulations provide the necessary domestic powers to enforce and administer our obligations under the European legislation. 4. Since March 2002, numerous amendments have been made to various articles and annexes in Regulation (EC) No. 999/2001. These amendments impact the procedures that are used in the feeding, slaughter, export and import, placing on the market, inspection and movement of cattle, sheep and goats. In response, a number of Statutory Instruments amending the TSE (Wales) Regulations 2002 have been made, namely: The Animal By-Products (Wales) Regulations 2003; The TSE (Wales) (Amendment) Regulations 2004; The TSE (Wales) (Amendment) Regulations 2005 and the TSE (Wales) (Amendment) (No.2) Regulations 2005. -

SHAWG Report 2016.Indd

SHAWG Sheep Health & Welfare Group Sheep Health and Welfare Report for Great Britain 2016/17 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Background to the report 2 3. Industry data and trends 3 4. Surveillance and monitoring 8 5. Internal parasites 11 6. External parasites 13 7. Lameness 14 8. Chronic wasting diseases 15 9. Common endemic diseases 17 10. Abortion 18 11. Ewe mortality 20 12. Lamb mortality 22 13. Abattoir data 24 14. Horizon scanning 26 15. Flock health planning 28 16. Use of medicines 29 17. Farm assurance 30 18. Breeding for health and welfare traits 31 19. Nutrition 32 20. Recommendations 33 References 34 Glossary 37 Appendix 40 About SHAWG 44 The SHAWG members would like to thank Kate Phillips, Harriet Fuller, Brian Lindsay and Ian Davies for their significant contribution to this report. 1. Introduction I am delighted to be writing this introduction for the very first Sheep Health and Welfare Report, instigated and commissioned by the Sheep Health and Welfare Group (SHAWG). The launch of this report supports the role of the SHAWG conferences that have become such popular and well attended events. These conferences reflect a sheep industry on the verge of a step change, to even further improvements in sheep health and welfare. It is anticipated that this report is part of that process. This document is purposely designed as a reference tool rather than a booklet to be read from cover to cover. One of the key roles of SHAWG is the coordination of industry initiatives in sheep health and welfare related activity. -

Wyefield Apiaries Label

ADRAN Y DEFAID • SHEEP SECTION The Society acknowledges with grateful thanks the assistance/sponsorship of the section by Greenlands Insurance Services Ltd, Farmplus Constructions Ltd, Ewe Moo Foot Rest, J. Straker, Chadwick and Sons, The Tack Room, Chilvers Country Supplies, Scotmin Nutrition NODIADAU CYFFREDINOL • CYMHWYSTER Sheep GENERAL NOTES • ELIGIBILITY Defaid 1. ALL SHEEP MUST BE NON MV ACCREDITED. 2. Exhibitors limited to two entries per class unless otherwise specified. 3. Any sheep displayed as part of a tradestand will NOT be eligible to enter in any of the competitive classes scheduled below. 4. The decisions relating to the allocation of particular breeds to the relevant sections scheduled shall be at the discretion of the Chief Steward whose decision will be final. The Society reserves the right to re-allocate entries where appropriate. 5. If extreme numbers of high entries are received for the event the Society reserves the right to take the necessary action deemed appropriate. 6. Please make sure that all sheep are entered in the correct class. Incorrect entries cannot be transferred. No animal can be entered in more than one section. 7. All sheep should be ‘shown to best advantage’ or as determined by their Breed Societies. 8. Appropriate pens will be allocated by the Chief Steward prior to the event. Each pen is approximately 1.5m x 1.5m. If space is available, the Society will also provide random tack pens. 9. Exhibitors: please note that during the judging of the section’s champion, second placed exhibits must be on standby, otherwise they will not be considered for judging. -

2017 June Newsletter

Cotswold Sheep Society Newsletter Registered Charity No. 1013326 June 2017 Mrs L. Millard, 18 Stephens Close, Downington, Lechlade on Thames, GL7 3FP Tel.: 07734 623173 [email protected] www.cotswoldsheepsociety.co.uk Council Officers Chairman – Miss D. Stanhope Acting Vice-Chairman – The Hon. Mrs. A. Reid Secretary - Ms. L. Millard Treasurer - Mrs. L. Parkes Council Members Mr. D. Cross, Mrs. C. Cunningham, The Hon. Mrs. A. Reid, Mr. S. Parkes, Mrs. M. Pursch, Mr. J. Dale Editor Mr. J. Flanders This Newsletter is independently edited and readers should be aware that the views expressed within its pages do not necessarily reflect the views held by Council. Lynne and Steve Parkes with the breeds of Gloucestershire taken outside Gloucester Cathedral EDITORIAL John Flanders Following the departure of John and Sherry Webb to Devon it was urgently necessary to appoint a replacement Secretary and Louise Millard has accepted the position; while she does not have sheep she has an interest in wool and is keen to promote the breed. As well as a having a new Secretary, Marie Louise French has kindly offered to become the new Editor of the Newsletter. Both ladies have supplied brief resumes of themselves. Also included is a fascinating article by Kate Elliott in which she compares different breeds of sheep and interestingly the bleat of our Cotswolds is different to that of our Teeswaters; also the Teeswaters are far more inquisitive and people friendly than the Cotswolds even though we have had the Cotswolds for nearly 25 years. We are indebted to John Hemmingway of Shropshire Farm Vets for kindly penning an article on the value of regular faecal egg counts. -

Scrapie-Resistant Sheep Show Certain Coat Colour Characteristics

Edinburgh Research Explorer Scrapie-resistant sheep show certain coat colour characteristics Citation for published version: Sawalha, RM, Bell, L, Brotherstone, S, White, I, Wilson, AJ & Villanueva, B 2009, 'Scrapie-resistant sheep show certain coat colour characteristics', Genetics Research, vol. 91, no. 1, pp. 39-46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016672308009968 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0016672308009968 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Genetics Research Publisher Rights Statement: RoMEO green General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Genet. Res., Camb. (2009), 91, pp. 39–46. f 2009 Cambridge University Press 39 doi:10.1017/S0016672308009968 Printed in the United Kingdom Scrapie-resistant sheep show certain coat colour characteristics R. M. SAWALHA1*, L. BELL2,S.BROTHERSTONE3,I.WHITE3,A.J.WILSON3 -

Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry

Yale Agrarian Studies Series James C. Scott, series editor 6329 Dohner / THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORIC AND ENDANGERED LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY BREEDS / sheet 1 of 528 Tseng 2001.11.19 14:07 Tseng 2001.11.19 14:07 6329 Dohner / THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORIC AND ENDANGERED LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY BREEDS / sheet 2 of 528 Janet Vorwald Dohner 6329 Dohner / THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORIC AND ENDANGERED LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY BREEDS / sheet 3 of 528 The Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds Tseng 2001.11.19 14:07 6329 Dohner / THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORIC AND ENDANGERED LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY BREEDS / sheet 4 of 528 Copyright © 2001 by Yale University. Published with assistance from the Louis Stern Memorial Fund. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Sonia L. Shannon Set in Bulmer type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Jostens, Topeka, Kansas. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dohner, Janet Vorwald, 1951– The encyclopedia of historic and endangered livestock and poultry breeds / Janet Vorwald Dohner. p. cm. — (Yale agrarian studies series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-300-08880-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Rare breeds—United States—Encyclopedias. 2. Livestock breeds—United States—Encyclopedias. 3. Rare breeds—Canada—Encyclopedias. 4. Livestock breeds—Canada—Encyclopedias. 5. Rare breeds— Great Britain—Encyclopedias. -

Organic Upland Beef and Sheep Production David Frost & Mair Morgan, ADAS Pwllpeiran Simon Moakes, IBERS

Organic Farming Technical Guide A farmer’s guide to Organic upland Beef and Sheep production David Frost & Mair Morgan, ADAS Pwllpeiran Simon Moakes, IBERS March 2009 Acknowledgements The editors gratefully acknowledge the following: Contributors: David Frost, ADAS Mair Morgan, ADAS Simon Moakes, IBERS (Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences) Pauline van Diepen, ADAS Photographs: Cover: David Frost and Welsh Assembly Government Funding Farming Connect Published by Organic Centre Wales, Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, SY23 3AL. Tel: 01970 622248 Organic Farming Technical Guide 1 Contents 1 The experience of ADAS Pwllpeiran .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 1.1 Background . 3 1.2 Grassland management .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 1.3 Management and performance of the suckler herd .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 1.4 Management and performance of the sheep flock .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 1.5 Beef and sheep feeding regimes .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .12 1.6 Summary and conclusions .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .