Colour Inheritance in Sheep III. Face and Leg Colour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Genetic Relationship Between Six Populations of Welsh Mountain Sheep Using Microsatellite Markers

This publication is made freely available under ______ __ open access. AUTHOR(S): TITLE: YEAR: Publisher citation: OpenAIR citation: Publisher copyright statement: This is the ______________________ version of an article originally published by ____________________________ in __________________________________________________________________________________________ (ISSN _________; eISSN __________). OpenAIR takedown statement: Section 6 of the “Repository policy for OpenAIR @ RGU” (available from http://www.rgu.ac.uk/staff-and-current- students/library/library-policies/repository-policies) provides guidance on the criteria under which RGU will consider withdrawing material from OpenAIR. If you believe that this item is subject to any of these criteria, or for any other reason should not be held on OpenAIR, then please contact [email protected] with the details of the item and the nature of your complaint. This publication is distributed under a CC ____________ license. ____________________________________________________ Original Paper Czech J. Anim. Sci., 60, 2015 (5): 216–223 doi: 10.17221/8171-CJAS Assessment of genetic relationship between six populations of Welsh Mountain sheep using microsatellite markers K.M. Huson, W. Haresign, M.J. Hegarty, T.M. Blackmore, C. Morgan, N.R. McEwan Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences, Penglais Campus, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, United Kingdom ABSTRACT: This study investigated the genetic relationship between 6 populations of Welsh Mountain sheep: 5 phenotypic breed-types within the Welsh Mountain (WM) sheep breed, which have each been bred in spe- cific geographic areas of Wales, and the Black Welsh Mountain sheep breed. Based on DNA analysis using 8 microsatellite markers, observed heterozygosity levels were similar to those expected in livestock populations subjected to selective breeding (0.530–0.664), and all but one population showed evidence of inbreeding. -

30297-Nidderdale 2012 Schedule 5:Layout 1

P R O G R A M M E (Time-table will be strictly adhered to where possible) ORDER OF JUDGING: Approx. 08.00 a.m. Breeding Hunters (commencing with Ridden Hunter Class) 09.00 a.m. Sheep Dog Trials 09.00 a.m. Carcass Class 09.00 a.m. Dogs Approx. 09.00 a.m. Riding and Turnout Approx. 09.00 a.m. Coloured Horse/Pony In-hand 09.15 a.m. Young Farmers’ Cattle 09.30 a.m. Dry Stone Walling Ballot 09.30 a.m. Beef Cattle (Local) 09.45 a.m. Sheep Approx. 10.00 a.m. All Other Cattle Judging commences Approx. 10.00 a.m. Children’s Riding Classes Approx. 10.00 a.m. Heavy Weight Agricultural Horses 10.00 a.m. Goats 10.00 a.m. Produce, Home Produce and Crafts (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Flowers, Vegetables and Farm Crops (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Poultry, Pigeons and Rabbits 10.30 a.m. ‘Pateley Pantry’ Stands Approx. 10.45 a.m. Mountain & Moorland 11.00 a.m. Pigs Approx. 11.00 a.m. Ridden Coloured 11.00 a.m. Trade Stands 1.15 p.m. Junior Shepherd/Shepherdess Classes (judged at the sheep pens) Approx. 2.00 p.m. Childrens’ Pet Classes (judged in the cattle rings) 2.00 p.m. Sheep - Supreme Championship MAIN RING ATTRACTIONS: 08.00-12.00 Judging - Horse and Pony classes 12.00-12.35 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 12.35-12.55 Terrier Racing 12.55-1.30 ATV Manoeuvrability Test 1.30-2.00 Young Farmers Mascot Football 2.00-2.20 Parade of Fox Hounds by West of Yore Hunt & Claro Beagles 2.20-3.00 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 3.00-3.30 GRAND PARADE AND PRESENTATION OF TROPHIES (Excluding Sheep, Goats, Pigs, Produce and WI) Parade of Tractors celebrating 8 decades of Nidderdale Young Farmers Club 3.30- Show Jumping OTHER ATTRACTIONS: Meltham & Meltham Mills Band playing throughout the day 12.00-12.15 St Cuthbert’s Primary School Band 12.15-1.15 Lofthouse & Middlesmoor Silver Band Forestry Exhibition Heritage Marquee Small Traders/Craft Marquee Pateley Pantry Marquee with Cookery Demonstrations 11.00 a.m. -

March Newsletter 2015 Final Version 3

Official Society Newsletter Ryeland Fbs Incorporating Coloured Ryeland News Spring 2015 Ryeland Lamb 2015 Ryeland Fbs Contact - Dot Tyne, Secretary, Ty’n y Mynydd Farm, Boduan, Pwllheli, Gwynedd, LL53 8PZ Telephone - 01758 721739 Email - [email protected] Opinions expressed by authors and services offered by advertisers are not specifically endorsed by the Ryeland Fbs. Advertisers must warrant that copy does not contravene, the Trades Description Act 1968. Sex Discrimination Act 1975 or The Business Advertisements (Disclosure) Order 1977 Newsletter Printed by SJH Print From The Editor Well first of all may I say a HAPPY NEW YEAR to you all. I hope you all enjoyed the Winter Newsletter, and found it fun and informative. Now to say Welcome to the new look newsletter, after a lot of research and proposals to council, we came up with this new design, The reason being we felt it 1 was time to bring this unique offering as a society up to date, it based on many different societies yearly newsletter, we are lucky enough to have one every quarter. In this newsletter we bring you a vast array of articles, From genetic updates, to a piece on the biggest sheep show in the UK. You will see that we have a few more changes in this newsletter, we have decided to make more of a feature of the Vets Articles making it an ‘Issue’ type article, Also we have decided to make more of a feature of the Coloured Ryeland News, with their own front cover making it the same as the overall newsletter. -

2012 June Newsletter

Cotswold Sheep Society Newsletter Registered Charity No. 1013326 June 2012 Hampton Rise, 1 High Street, Meysey Hampton, Gloucestershire, GL7 5JW Tel.: 01285 851197 [email protected] www.cotswoldsheepsociety.co.uk Council Officers Chairman – Mr. Richard Mumford Vice-Chairman – Mr. Thomas Jackson Secretary - Mrs. Lucinda Foster Treasurer- Mrs. Lynne Parkes Council Members Mrs. M. Pursch, Mrs. C. Cunningham, The Hon. Mrs. A. Reid, Mr. R Leach, Mr. D. Cross, Mr. S. Parkes, Ms. D. Stanhope Editors John Flanders, The Hon. Mrs. Angela Reid Spring at Cwmcrwth Farm (Towy Flock) EDITORIAL John Flanders This edition of the Newsletter contains a number of reminders of events that Council have organised and members are encouraged to support them. Council, in preparing a programme for the year, endeavours to provide subjects that meet the interests of all members, but if there is no support the question has to be asked whether there is any point in having these events. On a lighter note, I am delighted that Rob and Fiona Park have written about their flock of Cotswolds; it is always good to have a few more breeders in Wales. They also produce bacon and pork from the Oxford Sandy and Black rare breed pigs and I can vouch how tasty it is (mail order is available I understand). Sadly, despite my request in the last Newsletter, no one else has come forward to join Judy and me in The View From Here; similarly having tried to have a Young Handlers Section no contributions have been forthcoming. This year Davina Stanhope, Richard Mumford and Robin Leach are standing down from Council and I am grateful for the work that they have all put in on behalf of the Society. -

Gwartheg Prydeinig Prin (Ba R) Cattle - Gwartheg

GWARTHEG PRYDEINIG PRIN (BA R) CATTLE - GWARTHEG Aberdeen Angus (Original Population) – Aberdeen Angus (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Belted Galloway – Belted Galloway British White – Gwyn Prydeinig Chillingham – Chillingham Dairy Shorthorn (Original Population) – Byrgorn Godro (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol). Galloway (including Black, Red and Dun) – Galloway (gan gynnwys Du, Coch a Llwyd) Gloucester – Gloucester Guernsey - Guernsey Hereford Traditional (Original Population) – Henffordd Traddodiadol (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Highland - Yr Ucheldir Irish Moiled – Moel Iwerddon Lincoln Red – Lincoln Red Lincoln Red (Original Population) – Lincoln Red (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Northern Dairy Shorthorn – Byrgorn Godro Gogledd Lloegr Red Poll – Red Poll Shetland - Shetland Vaynol –Vaynol White Galloway – Galloway Gwyn White Park – Gwartheg Parc Gwyn Whitebred Shorthorn – Byrgorn Gwyn Version 2, February 2020 SHEEP - DEFAID Balwen - Balwen Border Leicester – Border Leicester Boreray - Boreray Cambridge - Cambridge Castlemilk Moorit – Castlemilk Moorit Clun Forest - Fforest Clun Cotswold - Cotswold Derbyshire Gritstone – Derbyshire Gritstone Devon & Cornwall Longwool – Devon & Cornwall Longwool Devon Closewool - Devon Closewool Dorset Down - Dorset Down Dorset Horn - Dorset Horn Greyface Dartmoor - Greyface Dartmoor Hill Radnor – Bryniau Maesyfed Leicester Longwool - Leicester Longwool Lincoln Longwool - Lincoln Longwool Llanwenog - Llanwenog Lonk - Lonk Manx Loaghtan – Loaghtan Ynys Manaw Norfolk Horn - Norfolk Horn North Ronaldsay / Orkney - North Ronaldsay / Orkney Oxford Down - Oxford Down Portland - Portland Shropshire - Shropshire Soay - Soay Version 2, February 2020 Teeswater - Teeswater Wensleydale – Wensleydale White Face Dartmoor – White Face Dartmoor Whitefaced Woodland - Whitefaced Woodland Yn ogystal, mae’r bridiau defaid canlynol yn cael eu hystyried fel rhai wedi’u hynysu’n ddaearyddol. Nid ydynt wedi’u cynnwys yn y rhestr o fridiau prin ond byddwn yn eu hychwanegu os bydd nifer y mamogiaid magu’n cwympo o dan y trothwy. -

First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

"First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources" (SoWAnGR) Country Report of the United Kingdom to the FAO Prepared by the National Consultative Committee appointed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Contents: Executive Summary List of NCC Members 1 Assessing the state of agricultural biodiversity in the farm animal sector in the UK 1.1. Overview of UK agriculture. 1.2. Assessing the state of conservation of farm animal biological diversity. 1.3. Assessing the state of utilisation of farm animal genetic resources. 1.4. Identifying the major features and critical areas of AnGR conservation and utilisation. 1.5. Assessment of Animal Genetic Resources in the UK’s Overseas Territories 2. Analysing the changing demands on national livestock production & their implications for future national policies, strategies & programmes related to AnGR. 2.1. Reviewing past policies, strategies, programmes and management practices (as related to AnGR). 2.2. Analysing future demands and trends. 2.3. Discussion of alternative strategies in the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 2.4. Outlining future national policy, strategy and management plans for the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 3. Reviewing the state of national capacities & assessing future capacity building requirements. 3.1. Assessment of national capacities 4. Identifying national priorities for the conservation and utilisation of AnGR. 4.1. National cross-cutting priorities 4.2. National priorities among animal species, breeds, -

Sheep-Raising in British Columbia

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPAETMENT OF AGEICTJLTTJEE (LIVE STOCK BRANCH). SHEEP-RAISING IN BRITISH COLUMBIA BULLETIN No. 77 (SECOND EDITION) PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OP THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. VICTORIA, B.C.: Printed by WILLIAM H. CULLIN, Printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty. 1921. PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPAKTMENT OF AGKICULTUKE (LIVE STOCK BRANCH). SHEEP-RAISfflG IN BRITISH COLUMBIA BULLETIN No. 77 (SECOND EDITION) PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. VICTORIA, B.C.: Printed by WILLIAM H. CULLIN, Printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty. 1921. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, VICTORIA, B.C., January Gth, 1921. To His Honour WALTER CAMERON NICHOL, Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR : I have the honour to submit herewith for your consideration th " second edition of Bulletin No. 77, Sheep-raising in British Columbia, which is reissued under the direction of Dr. D. Warnock, Deputy Ministe of Agriculture. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, E. D. BARROW, Minister of Agriculture. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, VICTORIA, B.C., January 6th, 1921. Hon. E. D. Barrow, M.L.A., Minister of Agriculture, Victoria, B.C. SIR, I have the honour to submit herewith for your approval th " second edition of Bulletin No. 77, Sheep-raising in British Columbia, which has been revised and is reissued owing to the steady demand fo information on this important branch of the live-stock industry. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, DAVID WARNOCK, V.S., O.B.E.. Deputy Minister of Agriculture. PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA. -

Farm Animals and Farming: Part 1

A GUIDE TO THE COUNTRYSIDE: FARM ANIMALS & FARMING by Hunter Adair Farm animals and farming: Part 1 When you are out in the countryside in the summer, you will see a great variety of animals running about in the fields, and if you happen to be travelling in the Dales, or in the hills you will mostly find sheep and probably suckler cattle, which are cows with their calves running with them. Some sheep are bred for the high hills and areas where the land is much less fertile than on the lowland farms. The hill bred sheep are hardy and can stand a great deal of rough weather. In the winter when a blizzard or snow storm is forecast the sheep will come down Judging Blue Face Leicester from the hill tops on their own to lower ground and shelter, they seem to know when a storm sheep at The Royal Highland is coming. Show In Edinburgh There are over 50 breeds of sheep in this country and many people from the towns and cities think one sheep is just like another. All the different breeds of sheep have their own characteristics and peculiarities. Some sheep are pure bred and some sheep are cross bred to get a particular lamb, which a farmer may prefer, and which may suit his farm. Some breeds of sheep have been developed in certain parts of the country and in certain areas, and the name of the sheep is taken from the district where they were born and bred. In Scotland for instance they have numerous breeds of sheep which are all different. -

1 a Lleyn Sweep for Local Sheep? Breed Societies and the Geographies of Welsh Livestock

A Lleyn Sweep for Local Sheep? Breed Societies and the Geographies of Welsh Livestock Richard Yarwood* and Nick Evans+ * School of Geography, University of Plymouth, Drake Circus, Plymouth, PL4 8AA. [email protected] 01752 233083 + Centre for Rural Research Department of Applied Sciences, Geography and Archaeology, University College Worcester, Henwick Grove, Worcester, WR2 6AJ. 01905 855197 [email protected] Abstract This paper uses Bourdieu’s (1977) concept of habitus to examine human-animal relationships within capitalist agricultural systems. The first part of the paper examines how Bourdieu’s ideas have been used by academics to provide insights into the ways that livestock affect and are affected by farming practice. The second part builds on these conceptual, empirical and policy insights by examining some of the national and international social networks that contribute to human-animal relationships in capitalistic farming. It focuses on a case study of Welsh livestock and, in particular, the historic and contemporary roles that breed societies play in the imagination of farm animals and the creation of capitals in agriculture. 1 A Lleyn Sweep for Local Sheep? Breed Societies and the Geographies of Welsh Livestock ‘The mountain sheep are sweeter, But the valley sheep are fatter; And so we deemed it meeter To take away the latter.’ „The War-Song of the Dinas Vawr‟ Thomas Love Peacock (1829) Introduction The relationships between animals, locality and society have come under increased scrutiny by geographers (Philo, 1995; Wolch and Emel, 1995; Wolch, 1998; Philo and Wilbert, 2000). An emerging body of literature is critically reappraising the place of animals within capitalist agricultural systems, reflecting the three main trajectories of animal geography (Whatmore, 2000). -

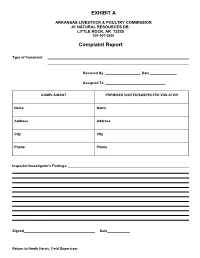

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

227 Sheep SHEEP DEPARTMENT Kelly Secord

SHEEP DEPARTMENT Kelly Secord- Superintendent Entry Information: Entries can be made online at livestockexpo.org. Entry Deadline and Fee October 10, 2020 Junior Breeding Sheep Entry Fee: $18.00 Junior Market Lamb Entry Fee: $30.00 Open Show Entry Fee: $20.00 Junior Breeding and Market Showmanship Entry Fee: $10.00 *Pre-Entry required* There will be a $25.00 service charge on all declined credit cards. Sheep Arrival Schedule Junior Breeding Sheep - November 11, 8:00 a.m. thru November 13, 12 Noon Junior Market Lambs/Commercial Ewes - November 11, 8:00 a.m. thru November 12, 12 Noon Open Breeding Sheep - November 11, 8:00 a.m. thru November 14, 4:00 p.m. Release Schedule Junior Sheep: Breeds will be released following completion of each BREED show. (Unless entered in Open show, then must follow open show release) Open Sheep: All breeds released upon completion of each breed's show unless showing in Supreme Selection, Thursday, November 19th. Stalling Information Stalling will be done based on number of entries. Stalling preferences must be put on entrty form to be taken into consideration. Pen size in South Wing A & B is 6x6 or 7X7. Feeders Supply - (502) 583-3867 Show Schedule WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 2020 8:00 a.m. Begin Receiving Sheep 12:00 Noon to 5:00 p.m. Breeding Sheep and Showmanship Check-In THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 2020 8:00 a.m. Continue Receiving Sheep 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Breeding Sheep and Showmanship Check-In 4:00 p.m. Market Lambs must be in place and weight cards turned in FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2020 8:00 a.m. -

Your Business Your Future A4 ADVERT 11/5/17 17:55 Page 1

Sheep FarmerAUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2017 A NATIONAL SHEEP ASSOCIATION PUBLICATION PROMOTING AND SELLING LAMB – DIRECT TO THE CUSTOMER TACKLING TOXOPLASMOSIS PRIOR TO TUPPING NSA POLICY UPDATE ROTATIONAL GRAZING STRATEGIES NSA REGIONAL EVENT REPORTS AND SALE PREVIEWS BLUETONGUE AND PNEUMONIA UPDATES your business your future A4 ADVERT 11/5/17 17:55 Page 1 Deliver thr Sheep oughouty assisted UK Defra is listening – Farmer August/September but it’s still early days 2017 edition Vol. 36, No 4 ISSN 0141-2434 A National Sheep Association publication. Each one of this year’s six regional NSA sheep events has been a huge Contents success and credit must go to the 2 News round-up event organisers and their committees, the armies of volunteers that help in 4 NSA reports: devolved nations advance and on the day, and – of course 6 NSA reports: English regions – the hosts. 8 NSA ram sale previews Without sounding like British Rail, one NSA Highland Sheep report or two events suffered with the weather 11 being too wet and one, in particular, saw 12 NSA North Sheep report conditions that were too hot. But you 14 NSA Sheep SW report have to take the rough with the smooth 15 NSA Sheep Northern Ireland and at least they took place – and were report on time! 16 Win a lamb weigh crate On a serious note, these events ministers are still keen to see our 18 perform a unique function. They are welfare standards go higher, even Latest NSA activity entirely sheep related business-to- though there is little evidence that 20 FARM FEATURE: former NSA Order your rams business and technically focussed we can use this within WTO rules to Chairman John Geldard shows.