Final Evaluation of the Environmentally Sustainable Food Security Programme (ESFSP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yangon University of Economics Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Programme

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE MASTER OF BANKING AND FINANCE PROGRAMME INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE (CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION) KHET KHET MYAT NWAY (MBF 4th BATCH – 30) DECEMBER 2018 INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION A thesis summited as a partial fulfillment towards the requirements for the Degree of Master of Banking and Finance (MBF) Supervised By : Submitted By: Dr. Daw Tin Tin Htwe Ma Khet Khet Myat Nway Professor MBF (4th Batch) - 30 Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Yangon University of Economics Yangon University of Economics ABSTRACT This study aims to identify the influencing factors on farms’ performance in Bogale Township. This research used both primary and secondary data. The primary data were collected by interviewing with farmers from 5 groups of villages. The sample size includes 150 farmers (6% of the total farmers of each village). Survey was conducted by using structured questionnaires. Descriptive analysis and linear regression methods are used. According to the farmer survey, the household size of the respondent is from 2 to 8 members. Average numbers of farmers are 2 farmers. Duration of farming experience is from 11 to 20 years and their main source of earning is farming. Their living standard is above average level possessing own home, motorcycle and almost they owned farmland and cows. The cultivated acre is 30 acres maximum and 1 acre minimum. Average paddy yield per acre is around about 60 bushels per acre for rainy season and 100 bushels per acre for summer season. -

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE of MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ;

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE OF MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ; © 2018, INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF RURAL RECONSTRUCTION This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original work is properly credited. Cette œuvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), qui permet l’utilisation, la distribution et la reproduction sans restriction, pourvu que le mérite de la création originale soit adéquatement reconnu. IDRC Grant/ Subvention du CRDI: 108748-001-Climate and nutrition smart villages as platforms to address food insecurity in Myanmar 33 IDRC \CRDl ..m..»...u...».._. »...m...~ c.-..ma..:«......w-.«-.n. ...«.a.u CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE PROFILE Ma Sein Village Bogale Township, Ayeyarwaddy Region 2 Climate Smart Village Profile Introduction Myanmar is the second largest country in Southeast Asia bordering Bangladesh, Thailand, China, India, and Laos. It has rich natural resources – arable land, forestry, minerals, natural gas, freshwater and marine resources, and is a leading source of gems and jade. A third of the country’s total perimeter of 1,930 km (1,200 mi) is coastline that faces the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. The country’s population is estimated to be at 60 million. Agriculture is important to the economy of Myanmar, accounting for 36% of its economic output (UNDP 2011a), a majority of the country’s employment (ADB 2011b), and 25%–30% of exports by value (WB–WDI 2012). -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Burma

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO BURMA RANGOON CITY AREA AFFECTED AREAS Affected Townships (as reported by the Government of Burma) American Red Cross aI SOURCE: MIMU ASEAN B Implementing NGO aD BAGO DIVISION IOM B Kyangin OCHA B (WEST) UNHCR I UNICEF DG JF Myanaung WFP E Seikgyikanaunglo WHO D UNICEF a WFP Ingapu DOD E RAKHINE b AYEYARWADY Dala STATE DIVISION UNICEF a Henzada WC AC INFORMA Lemyethna IC TI Hinthada PH O A N Rangoon R U G N O I T E G AYEYARWADY DIVISION ACF a U Zalun S A Taikkyi A D ID F MENTOR CARE a /DCHA/O D SC a Bago Yegyi Kyonpyaw Danubyu Hlegu Pathein Thabaung Maubin Twantay SC RANGOON a CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE AC Hmawbi See Inset WC AC Htantabin Kyaunggon DIVISION Myaungmya Kyaiklat Nyaungdon Kayan Pathein Einme Rangoon SC/US JCa CWS/IDE AC Mayangone ! Pathein WC AC Î (Yangon) Thongwa Thanlyin Mawlamyinegyun Maubin Kyauktan Kangyidaunt Twantay CWS/IDE AC Myaungmya Wakema CWS/IDE Kyauktan AC PACT CIJ Myaungmya Kawhmu SC a Ngapudaw Kyaiklat Mawlamyinegyun Kungyangon UNDP/PACT C Kungyangon Mawlamyinegyun UNICEF Bogale Pyapon CARE a a Kawhmu Dedaye CWS/IDE AC Set San Pyapon Ngapudaw Labutta CWS/IDE AC UNICEF a CARE a IRC JEDa UNICEF a WC Set San AC SC a Ngapudaw Labutta Bogale KEY SC/US JCa USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP DOD Pyinkhayine Island Bogale A Agriculture and Food Security SC JC a Air Transport ACTED AC b Coordination and Information Management Labutta ACF a Pyapon B Economy and Market Systems CARE C !Thimphu ACTED a CARE Î AC a Emergency Food Assistance ADRA CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE aIJ AC Emergency Relief Supplies Dhaka IOM a Î! CWS/IDE AC a UNICEF a D Health BURMA MERLIN PACT CJI DJ E Logistics PACT ICJ SC a Dedaye Vientiane F Nutrition Î! UNDP/PACT Rangoon SC C ! a Î ACTED AC G Protection UNDP/PACT C UNICEF a Bangkok CARE a IShelter and Settlements Î! UNICEF a WC AC J Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene WC WV GCJI AC 12/19/08 The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. -

Appendix 6 Satellite Map of Proposed Project Site

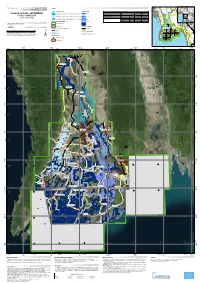

APPENDIX 6 SATELLITE MAP OF PROPOSED PROJECT SITE Hakha Township, Rim pi Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village A6-1 Falam Township, Webula Village Tract, Chin State Kim Mon Chaung Village A6-2 Webula Village Pa Mun Chaung Village Tedim Township, Dolluang Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village Dolluang Village A6-3 Taunggyi Township, Kyauk Ni Village Tract, Shan State A6-4 Kalaw Township, Myin Ma Hti Village Tract and Baw Nin Village Tract, Shan State A6-5 Ywangan Township, Sat Chan Village Tract, Shan State A6-6 Pinlaung Township, Paw Yar Village Tract, Shan State A6-7 Symbol Water Supply Facility Well Development by the Procurement of Drilling Rig Nansang Township, Mat Mon Mun Village Tract, Shan State A6-8 Nansang Township, Hai Nar Gyi Village Tract, Shan State A6-9 Hopong Township, Nam Hkok Village Tract, Shan State A6-10 Hopong Township, Pawng Lin Village Tract, Shan State A6-11 Myaungmya Township, Moke Soe Kwin Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-12 Myaungmya Township, Shan Yae Kyaw Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-13 Labutta Township, Thin Gan Gyi Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Protection Dike Rainwater Pond (New) : 5 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) : 20 Facilities A6-14 Labutta Township, Laput Pyay Lae Pyauk Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-15 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Irrigation Channel Rainwater Pond (New) : 2 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) Hinthada Township, Tha Si Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-16 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road -

Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area Delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R

Nepal (!Loikaw GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR130 I Legend r n r India China e Product N.: 16IRRAWADDYDELTA, v2, English Magway a Rakhine w Bangladesh e a w l d a Vietnam Crisis Information Hydrology Consequences within the AOI on 09, 10, 11/08/2015 d Myanmar S Affected Total in AOI y Nay Pyi Taw Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R ha 428922,1 i v Laos Flooded area e ^ r S Flood - 01/08/2015 Flooded Area delineation 10/08/2015 23:49 UTC Stream Estimated population Inhabitants 4252141 11935674 it Bay of ( to Settlements Built-up area ha 35491,8 75542,0 A 10 Bago n Bengal Thailand y g Delineation Map e Flooded Area delineation 09/08/2015 11:13 UTC Lake y P Transportation Railways km 26,0 567,6 a Cambodia r i w Primary roads km 33,0 402,1 Andam an n a Gulf of General Information d Sea g Reservoir Secondary roads km 57,2 1702,3 Thailand 09 y Area of Interest ) Andam an Cartographic Information River Sea Missing data Transportation Bay of Bengal 08 Bago Tak Full color ISO A1, low resolution (100 dpi) 07 1:600000 Ayeyarwady Yangon (! Administrative boundaries Railway Kayin 0 12,5 25 50 Region km Primary Road Pathein 06 04 11 12 (! Province Mawlamyine Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N map coordinate system Secondary Road 13 (! Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ± Settlements 03 02 01 ! Populated Place 14 15 Built-Up Area Gulf of Martaban Andaman Sea 650000 700000 750000 800000 850000 900000 950000 94°10'0"E 94°35'0"E 95°0'0"E 95°25'0"E 95°50'0"E 96°15'0"E 96°40'0"E 97°5'0"E N " 0 ' 5 -

Myanmar-Government-Projects.Pdf

Planned Total Implementing Date Date Last Project Project Planned Funding Financing Tender Developer Sector Sr. Project ID Description Expected Benefits End Project Government Ministry Townships Sectors MSDP Alignment Project URL Created Modified Title Status Start Date Sources Information Date Name Categories Date Cost Agency The project will involve redevelopment of a 25.7-hectare site The project will provide a safe, efficient and around the Yangon Central Railway Station into a new central comfortable transport hub while preserving the transport hub surrounded by housing and commercial heritage value of the Yangon Central Railway Station amenities. The transport hub will blend heritage and modern and other nearby landmarks. It will be Myanmar’s first development by preserving the historic old railway station main ever transit-oriented development (TOD) – bringing building, dating back in 1954, and linking it to a new station residential, business and leisure facilities within a constructed above the rail tracks. The mixed-use development walking distance of a major transport interchange. will consist of six different zones to include a high-end Although YCR railway line have been upgraded, the commercial district, office towers, condominiums, business image and performance of existing railway stations are hotels and serviced apartments, as well as a green park and a still poor and low passenger services. For that railway museum. reason, YCR stations are needed to be designed as Yangon Circular Railway Line was established in 1954 and it has attractive, comfortable and harmonized with city been supporting forYangon City public transportation since last development. On the other hand, we also aligned the 60 years ago. -

The Myanmar-Thailand Corridor 6 the Myanmar-Malaysia Corridor 16 the Myanmar-Korea Corridor 22 Migration Corridors Without Labor Attachés 25

Online Appendixes Public Disclosure Authorized Labor Mobility As a Jobs Strategy for Myanmar STRENGTHENING ACTIVE LABOR MARKET POLICIES TO ENHANCE THE BENEFITS OF MOBILITY Public Disclosure Authorized Mauro Testaverde Harry Moroz Public Disclosure Authorized Puja Dutta Public Disclosure Authorized Contents Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar 1 Appendix 2 Forms used to collect information at Labor Exchange Offices 3 Appendix 3 Registering jobseekers and vacancies at Labor Exchange Offices 5 Appendix 4 The migration process in Myanmar 6 The Myanmar-Thailand corridor 6 The Myanmar-Malaysia corridor 16 The Myanmar-Korea corridor 22 Migration corridors without labor attachés 25 Appendix 5 Obtaining an Overseas Worker Identification Card (OWIC) 29 Appendix 6 Obtaining a passport 30 Cover Photo: Somrerk Witthayanant/ Shutterstock Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar State/Region Name State/Region Name Yangon No (1) LEO Tanintharyi Dawei Township Office Yangon No (2/3) LEO Tanintharyi Myeik Township Office Yangon No (3) LEO Tanintharyi Kawthoung Township Office Yangon No (4) LEO Magway Magwe Township Office Yangon No (5) LEO Magway Minbu District Office Yangon No (6/11/12) LEO Magway Pakokku District Office Yangon No (7) LEO Magway Chauk Township Office Yangon No (8/9) LEO Magway Yenangyaung Township Office Yangon No (10) LEO Magway Aunglan Township Office Yangon Mingalardon Township Office Sagaing Sagaing District Office Yangon Shwe Pyi Thar Township Sagaing Monywa District Office Yangon Hlaing Thar Yar Township Sagaing Shwe -

Environmentally Sustainable Food Security Programme (ESFSP)

Environmentally Sustainable Food Security Programme (ESFSP) Brief on the project “Support to the immediate rehabilitation of farming, coastal fisheries & aquaculture livelihoods in the cyclone Nargis-affected areas of Myanmar” (GCP/MYA/012/ITA) Demonstration plot of rice registered seed in Pyapon A. Outcomes and Outputs The project aims at sustainable improvements in household food production, nutritional status and income- generating activities among households and communities that comprise landless, marginal and small-scale farmers and fishers in the cyclone-affected townships of Bogale, Labutta and Pyapon. Output 1: Impoverished rural communities mobilized to benefit from improved agricultural support services 115 farmer field schools (FFS), 74 demonstration plots (DP) and 2 seed multiplication groups (SMG) have been implemented with 4 partners in 70 villages located in 20 village tracts, directly involving 7,200 farmers. Training covered to specific needs of each FFS group related to crop cycle management; conservation agriculture; integrated plant nutrient management systems; integrated pest management; postharvest technology for reducing pre- and post-harvest losses, and on-farm storage techniques; establishment and functioning of the rice bank system; crop intensification for rice-based cropping systems; and disaster risk management. Output 2: Enhanced long-term land productivity, reduced food insecurity and improved household nutritional status of impoverished farming communities This is mainly achieved through provision of seed of improved local varieties of rice, pulses and other crops; farm tools and equipment; transfer of improved technologies through the implementation of Farmer Field Schools (FFS); adoption of improved farming systems; formation and strengthening of farmers’ groups; establishment of revolving funds and matching contributions. -

UNDP Myanmar Responds to Cyclone Nargis

UNDP Myanmar responds MATTERS OF FACT to Cyclone Nargis • 40 UNDP and its implementing partner NGO PACT offices in the Ayeyarwady Delta UNDP moved into action within 24 hours after Cyclone • 23 field teams active in the worst affected areas Nargis hit Myanmar on 2-3 May. The storm carved a • 500 national staff and project personnel working in the path of destruction that left 133,653 dead or missing delta and being mobilized for Cyclone Nargis response and 2.4 million severely affected by the crisis. operations • 5 UNDP offices functioning as ‘base camp’ for UN The cyclone’s 120-mile per hour winds and resulting organizations and international NGOs delivering to, and storm surge were particularly devastating in the working in Bogale, Mawlamyinegyun, Labutta, Ayeyarwady Delta, where entire villages were flattened. Ngapudaw and Kyaiklat • 2.4 million people severely affected by Cyclone UNDP is the only UN organization with field offices Nargis across Myanmar located in the region, which, prior to the cyclone was • 1.4 million people affected in the Ayeyarwady delta, home to seven million people. UNDP staff and families the hardest hit region of Myanmar experienced the natural disaster first-hand, as did those • 43,241 estimated total beneficiaries from UNDP coordinated relief efforts as of 21 May who work for partner non-governmental organization (NGO) PACT, which lost five of its project personnel. Supporting relief efforts: UNDP sent rotating teams UNDP has 40 functioning field offices in the delta and of national staff to work with and relieve its field staff in current field staff strength of more than 500 five of the affected townships – Bogale, experienced national staff and project personnel, Mawlamyinegyun, Labutta, Ngapudaw and Kyaiklat – including those of PACT. -

Ayeyarwady Delta 3CRP Scoping Mission

Ayeyarwady Delta 3CRP Scoping Mission 02nd to 07th February 2014 Summary of key findings and proposed next steps WorldFish (AAS) / IRRI (GRiSP) / IWMI (WLE) IRRI: Grant Singleton, Madonna Casimero, Elizabeth Humphreys, Matty Demont IWMI: Matthew McCartney, Chu Thai Hoanh, Sonali Senaratna, Srabani Roy WorldFish: Gareth Johnstone, Michael Phillips, Ranjitha Puskur, Kam Suan Pheng, Tezzo Xavier 1 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank staff from the Myanmar Department of Fisheries for their assistance in organizing the logistics for this scoping mission with a special thanks to U Khin Maung Soe who organized much of the logistics for the dry-run and scoping missions. They also extend their thanks to the numerous people who kindly gave their time for interviews and focus group discussions. Financial support for the mission was provided by the CGIAR Research Programs: i) the Global Rice Science Partnership, ii) Aquatic Agricultural Systems, and iii) Water Land and Ecosystems. i Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. i Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ iii Acronyms and Abbreviations .................................................................................................................. v SECTION 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................... -

Myanmar Woodfuels Sector Assessment

Public Disclosure Authorized MYANMAR WOODFUELS SECTOR Public Disclosure Authorized ASSESSMENT JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: AUS0001529 . Myanmar Country Forest Note WOODFUELS SECTOR ASSESSMENT . June 2020 . Environment, Natural Resources and The Blue Economy Global Practice . © 2020 The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: “World Bank. 2020. Myanmar Woodfuels Sector Assessment. © World Bank.” All queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................................. -

Northern Lights Template

Rotary International Zone 22 Russia • USA • Canada • France N N N N May/June 2008 Rotary World Peace Summit o o o A Newsletter for a Huge Success! o Those of us who were fortunate vision it was to hold the Summit) Rotary Leaders in enough to attend the Rotary World received outstanding support from r r r Zone 22 Peace summit held in Windsor are RI President Wilf Wilkinson and r t t t happy to report that it was one of Honorary Chair Allan Rock (Canada’s t the most rewarding experiences of Ambassador to the UN, 2004-06). h h h Editor: Elly Contreras-Vermeulen h Send your submissions before our Rotary lives! “We came away International Co-Chairs PRID John July 15 to [email protected] with the re-confirmed knowledge Eberhard and PRID Mike McCullough e that Rotary is on the right track to did a superb job involving nearly 100 e e e making peace possible, because committee members and volunteers. peace is possible.” - an unsolicited Among the headline speakers were r r r comment from one of the delegates Prince Zeid Ra’ad, Jordan’s r attending the fourth and final Ambassador to the USA, Nobel Peace n n n Rotary peace forum this year. Prize Nominee Lloyd Axworthy and n Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. The United States and Canada have Prominent Rotary speakers included enjoyed the longest and oldest RIP Wilf Wilkinson, TRF Chair Bob L L L unprotected border between two Scott and Rotary Peace Fellows. L IMPORTANT DATES great nations.