Ayeyarwady Delta 3CRP Scoping Mission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yangon University of Economics Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Programme

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE MASTER OF BANKING AND FINANCE PROGRAMME INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE (CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION) KHET KHET MYAT NWAY (MBF 4th BATCH – 30) DECEMBER 2018 INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION A thesis summited as a partial fulfillment towards the requirements for the Degree of Master of Banking and Finance (MBF) Supervised By : Submitted By: Dr. Daw Tin Tin Htwe Ma Khet Khet Myat Nway Professor MBF (4th Batch) - 30 Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Yangon University of Economics Yangon University of Economics ABSTRACT This study aims to identify the influencing factors on farms’ performance in Bogale Township. This research used both primary and secondary data. The primary data were collected by interviewing with farmers from 5 groups of villages. The sample size includes 150 farmers (6% of the total farmers of each village). Survey was conducted by using structured questionnaires. Descriptive analysis and linear regression methods are used. According to the farmer survey, the household size of the respondent is from 2 to 8 members. Average numbers of farmers are 2 farmers. Duration of farming experience is from 11 to 20 years and their main source of earning is farming. Their living standard is above average level possessing own home, motorcycle and almost they owned farmland and cows. The cultivated acre is 30 acres maximum and 1 acre minimum. Average paddy yield per acre is around about 60 bushels per acre for rainy season and 100 bushels per acre for summer season. -

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE of MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ;

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE OF MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ; © 2018, INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF RURAL RECONSTRUCTION This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original work is properly credited. Cette œuvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), qui permet l’utilisation, la distribution et la reproduction sans restriction, pourvu que le mérite de la création originale soit adéquatement reconnu. IDRC Grant/ Subvention du CRDI: 108748-001-Climate and nutrition smart villages as platforms to address food insecurity in Myanmar 33 IDRC \CRDl ..m..»...u...».._. »...m...~ c.-..ma..:«......w-.«-.n. ...«.a.u CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE PROFILE Ma Sein Village Bogale Township, Ayeyarwaddy Region 2 Climate Smart Village Profile Introduction Myanmar is the second largest country in Southeast Asia bordering Bangladesh, Thailand, China, India, and Laos. It has rich natural resources – arable land, forestry, minerals, natural gas, freshwater and marine resources, and is a leading source of gems and jade. A third of the country’s total perimeter of 1,930 km (1,200 mi) is coastline that faces the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. The country’s population is estimated to be at 60 million. Agriculture is important to the economy of Myanmar, accounting for 36% of its economic output (UNDP 2011a), a majority of the country’s employment (ADB 2011b), and 25%–30% of exports by value (WB–WDI 2012). -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Burma

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO BURMA RANGOON CITY AREA AFFECTED AREAS Affected Townships (as reported by the Government of Burma) American Red Cross aI SOURCE: MIMU ASEAN B Implementing NGO aD BAGO DIVISION IOM B Kyangin OCHA B (WEST) UNHCR I UNICEF DG JF Myanaung WFP E Seikgyikanaunglo WHO D UNICEF a WFP Ingapu DOD E RAKHINE b AYEYARWADY Dala STATE DIVISION UNICEF a Henzada WC AC INFORMA Lemyethna IC TI Hinthada PH O A N Rangoon R U G N O I T E G AYEYARWADY DIVISION ACF a U Zalun S A Taikkyi A D ID F MENTOR CARE a /DCHA/O D SC a Bago Yegyi Kyonpyaw Danubyu Hlegu Pathein Thabaung Maubin Twantay SC RANGOON a CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE AC Hmawbi See Inset WC AC Htantabin Kyaunggon DIVISION Myaungmya Kyaiklat Nyaungdon Kayan Pathein Einme Rangoon SC/US JCa CWS/IDE AC Mayangone ! Pathein WC AC Î (Yangon) Thongwa Thanlyin Mawlamyinegyun Maubin Kyauktan Kangyidaunt Twantay CWS/IDE AC Myaungmya Wakema CWS/IDE Kyauktan AC PACT CIJ Myaungmya Kawhmu SC a Ngapudaw Kyaiklat Mawlamyinegyun Kungyangon UNDP/PACT C Kungyangon Mawlamyinegyun UNICEF Bogale Pyapon CARE a a Kawhmu Dedaye CWS/IDE AC Set San Pyapon Ngapudaw Labutta CWS/IDE AC UNICEF a CARE a IRC JEDa UNICEF a WC Set San AC SC a Ngapudaw Labutta Bogale KEY SC/US JCa USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP DOD Pyinkhayine Island Bogale A Agriculture and Food Security SC JC a Air Transport ACTED AC b Coordination and Information Management Labutta ACF a Pyapon B Economy and Market Systems CARE C !Thimphu ACTED a CARE Î AC a Emergency Food Assistance ADRA CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE aIJ AC Emergency Relief Supplies Dhaka IOM a Î! CWS/IDE AC a UNICEF a D Health BURMA MERLIN PACT CJI DJ E Logistics PACT ICJ SC a Dedaye Vientiane F Nutrition Î! UNDP/PACT Rangoon SC C ! a Î ACTED AC G Protection UNDP/PACT C UNICEF a Bangkok CARE a IShelter and Settlements Î! UNICEF a WC AC J Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene WC WV GCJI AC 12/19/08 The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. -

Appendix 6 Satellite Map of Proposed Project Site

APPENDIX 6 SATELLITE MAP OF PROPOSED PROJECT SITE Hakha Township, Rim pi Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village A6-1 Falam Township, Webula Village Tract, Chin State Kim Mon Chaung Village A6-2 Webula Village Pa Mun Chaung Village Tedim Township, Dolluang Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village Dolluang Village A6-3 Taunggyi Township, Kyauk Ni Village Tract, Shan State A6-4 Kalaw Township, Myin Ma Hti Village Tract and Baw Nin Village Tract, Shan State A6-5 Ywangan Township, Sat Chan Village Tract, Shan State A6-6 Pinlaung Township, Paw Yar Village Tract, Shan State A6-7 Symbol Water Supply Facility Well Development by the Procurement of Drilling Rig Nansang Township, Mat Mon Mun Village Tract, Shan State A6-8 Nansang Township, Hai Nar Gyi Village Tract, Shan State A6-9 Hopong Township, Nam Hkok Village Tract, Shan State A6-10 Hopong Township, Pawng Lin Village Tract, Shan State A6-11 Myaungmya Township, Moke Soe Kwin Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-12 Myaungmya Township, Shan Yae Kyaw Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-13 Labutta Township, Thin Gan Gyi Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Protection Dike Rainwater Pond (New) : 5 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) : 20 Facilities A6-14 Labutta Township, Laput Pyay Lae Pyauk Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-15 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Irrigation Channel Rainwater Pond (New) : 2 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) Hinthada Township, Tha Si Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-16 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road -

(Myanmar) | COVID -19 November 11, 2020 Update 12

Registration Number: No. 115646346 British Chamber of Commerce Myanmar Suite No #06-04, Level - 6 Junction City Tower Pabedan Township Yangon, Myanmar Country Report (Myanmar) | COVID -19 November 11, 2020 Update 12 The British Chamber of Commerce Myanmar will consolidate the various regulations into one document. We cannot 100% confirm that all the reports are accurate and are intended as a guideline only. We will provide updates as and when new information emerges. Members can also refer to the UK Government Travel Advice. 1. COVID-19 Confirmed Cases Dashboard of Ministry of Health and Sports and the Situation Update Daily Report. See here Emergency Call Center 067 3420268 – Public Health Emergency Center, Nay Pyi Taw 09 449001261, 09 794510057 – COVID 19 Call Center for Yangon Region 09 2000344, 09 43099526 – COVID 19 Call Center for Mandalay Region Government Policy Update For COVID- 19 Precautions National-Level Central Committee on Prevention, Control and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease released the Announcement on Extension of the Precautionary Restriction Measures Related to Control of COVID-19 Pandemic until 30th November 2020. Official Announcement According to the notice from the Department of Civil Aviation, the International Airport has been further extended up to until 30th November 2020. Announcement on Temporary suspension of all types of visas for foreign nationals from all countries visiting Myanmar: Official Link Those members wishing to return to Myanmar from overseas, need to contact the Myanmar Embassy in the first instance. Page 1 of 15 Aviation Sector The aviation department said it is carrying out relief flights for Myanmar citizens stranded in Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Bangkok, India and Sydney. -

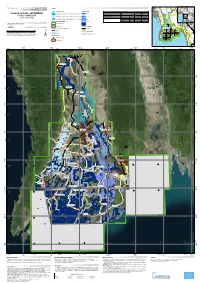

Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area Delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R

Nepal (!Loikaw GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR130 I Legend r n r India China e Product N.: 16IRRAWADDYDELTA, v2, English Magway a Rakhine w Bangladesh e a w l d a Vietnam Crisis Information Hydrology Consequences within the AOI on 09, 10, 11/08/2015 d Myanmar S Affected Total in AOI y Nay Pyi Taw Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R ha 428922,1 i v Laos Flooded area e ^ r S Flood - 01/08/2015 Flooded Area delineation 10/08/2015 23:49 UTC Stream Estimated population Inhabitants 4252141 11935674 it Bay of ( to Settlements Built-up area ha 35491,8 75542,0 A 10 Bago n Bengal Thailand y g Delineation Map e Flooded Area delineation 09/08/2015 11:13 UTC Lake y P Transportation Railways km 26,0 567,6 a Cambodia r i w Primary roads km 33,0 402,1 Andam an n a Gulf of General Information d Sea g Reservoir Secondary roads km 57,2 1702,3 Thailand 09 y Area of Interest ) Andam an Cartographic Information River Sea Missing data Transportation Bay of Bengal 08 Bago Tak Full color ISO A1, low resolution (100 dpi) 07 1:600000 Ayeyarwady Yangon (! Administrative boundaries Railway Kayin 0 12,5 25 50 Region km Primary Road Pathein 06 04 11 12 (! Province Mawlamyine Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N map coordinate system Secondary Road 13 (! Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ± Settlements 03 02 01 ! Populated Place 14 15 Built-Up Area Gulf of Martaban Andaman Sea 650000 700000 750000 800000 850000 900000 950000 94°10'0"E 94°35'0"E 95°0'0"E 95°25'0"E 95°50'0"E 96°15'0"E 96°40'0"E 97°5'0"E N " 0 ' 5 -

Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma

To: Hon. Mr. Ban Ki-moon Secretary-General United Nations From: Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma CC: Mr. B. Lynn Pascoe, Under-Secretary-General, United Nations Mr. Ibrahim Gambari, Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser to the Secretary- General on Myanmar/Burma Permanent Representatives to the United Nations of the five Permanent Members (China, Russia, France, United Kingdom and the United states) of the UN Security Council U Aung Shwe, Chairman, National League for Democracy Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, General Secretary, National League for Democracy U Aye Thar Aung, Secretary, Committee Representing the Peoples' Parliament (CRPP) Veteran Politicians The 88 Generation Students Date: 1 August 2007 Re: National Reconciliation and Democratization in Myanmar/Burma Dear Excellency, We note that you have issued a statement on 18 July 2007, in which you urged the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) (the ruling military government of Myanmar/Burma) to "seize this opportunity to ensure that this and subsequent steps in Myanmar's political roadmap are as inclusive, participatory and transparent as possible, with a view to allowing all the relevant parties to Myanmar's national reconciliation process to fully contribute to defining their country's future."1 We thank you for your strong and personal involvement in Myanmar/Burma and we expect that your good offices mandate to facilitating national reconciliation in Myanmar/Burma would be successful. We, Members of Parliament elected by the people of Myanmar/Burma in the 1990 general elections, also would like to assure you that we will fully cooperate with your good offices and the United Nations in our effort to solve problems in Myanmar/Burma peacefully through a meaningful, inclusive and transparent dialogue. -

The Myanmar-Thailand Corridor 6 the Myanmar-Malaysia Corridor 16 the Myanmar-Korea Corridor 22 Migration Corridors Without Labor Attachés 25

Online Appendixes Public Disclosure Authorized Labor Mobility As a Jobs Strategy for Myanmar STRENGTHENING ACTIVE LABOR MARKET POLICIES TO ENHANCE THE BENEFITS OF MOBILITY Public Disclosure Authorized Mauro Testaverde Harry Moroz Public Disclosure Authorized Puja Dutta Public Disclosure Authorized Contents Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar 1 Appendix 2 Forms used to collect information at Labor Exchange Offices 3 Appendix 3 Registering jobseekers and vacancies at Labor Exchange Offices 5 Appendix 4 The migration process in Myanmar 6 The Myanmar-Thailand corridor 6 The Myanmar-Malaysia corridor 16 The Myanmar-Korea corridor 22 Migration corridors without labor attachés 25 Appendix 5 Obtaining an Overseas Worker Identification Card (OWIC) 29 Appendix 6 Obtaining a passport 30 Cover Photo: Somrerk Witthayanant/ Shutterstock Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar State/Region Name State/Region Name Yangon No (1) LEO Tanintharyi Dawei Township Office Yangon No (2/3) LEO Tanintharyi Myeik Township Office Yangon No (3) LEO Tanintharyi Kawthoung Township Office Yangon No (4) LEO Magway Magwe Township Office Yangon No (5) LEO Magway Minbu District Office Yangon No (6/11/12) LEO Magway Pakokku District Office Yangon No (7) LEO Magway Chauk Township Office Yangon No (8/9) LEO Magway Yenangyaung Township Office Yangon No (10) LEO Magway Aunglan Township Office Yangon Mingalardon Township Office Sagaing Sagaing District Office Yangon Shwe Pyi Thar Township Sagaing Monywa District Office Yangon Hlaing Thar Yar Township Sagaing Shwe -

Final Evaluation of the Environmentally Sustainable Food Security Programme (ESFSP)

OFFICE OF EVALUATION Project evaluation series Final Evaluation of the Environmentally Sustainable Food Security Programme (ESFSP) July 2017 PROJECT EVALUATION SERIES Final Evaluation of the Environmentally Sustainable Food Security Programme (ESFSP) FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS OFFICE OF EVALUATION July 2017 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Office of Evaluation (OED) This report is available in electronic format at: http://www.fao.org/evaluation The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. © FAO 2017 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. -

Dedaye Min Hla Su Kyon Tar Shan Kwin

Myanmar Information Management Unit Gon Min Kwin (Gon Min Kwin) Village Tract Map of Pyapon Township Kyaiklat 95°20'E 95°40'E Hlwa Htaung Su Kyaiklat Bago Gyo War Kyauk Ye Su Dedaye Min Hla Su Kyon Tar Shan Kwin Ma Ye Pyar Mut Gyo War Kyan Khin Su Tha Leik Gyi Ayeyarwady Kyon Kyaik Yangon Kha Naung Shan Kwin 16°20'N Ah See Ka Lay 16°20'N Gyon War Hta Lun Chaung Twin Thea Bant Bway Su Ein Kyon Thut Kyon Ku Kyaung Ta Nyi Su Thea Ein Dedaye Bogale Ta Man Koe Ein Tan Pyapon Ta Man Pyapon Ah Pyaung Hmaw Bi Ka Zaung Kyee Hnit Pin Ah Char Kha Yaing Baw Ah Htet Tha Pyay Kan Ah Char Ka Lay Thone Htat Kyaik Ka Bar Tha Mein Htaw Kone Tan Gay Gu Ka Ni Ah Lan Hpa Lut Tha Mein Htaw Thein Kone Byaing Ka Hpee Auk Ka Bar Zin Baung Tin Pu Lwe Kyet Hpa Mway Zaung Bogale Let Pan Pin Kyon Ka Dun 16°0'N Day Da Lu (Ah Mar Sub-township) 16°0'N Myo Kone Daw Nyein Kyaung Kone Boe Ba Kone Seik Ma Ahmar Ka Don Ka Ni Nauk Mee Ba Wa Thit Kilometers 0 1.5 3 6 9 12 95°20'E 95°40'E Map ID: MIMU224v01 Data Sourse: GLIDE Number: TC-2008-000057-MMR Towns Coast Village Tract Boundary Base Map - MIMU;Boundaries - WFP/MIMU Creation Date: 8 December 2010. A4 Road Township Boundary Place names - Ministry of Home Affair Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 River and Stream District Boundary (GAD) translated by MIMU Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] State Boundary www.themimu.info Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

Myanmar Transport Brief ANALYSIS Issue 17 DATA TENDERS 30 March 2017 COMPANIES

NEWS Myanmar Transport Brief ANALYSIS DATA Issue 17 TENDERS 30 March 2017 COMPANIES Part of the Myanmar Transport Monitor transport.frontiermyanmar.com IN THIS ISSUE Ministry backs off corporatisation plan for Inland Water Transport Plans to transform state-owned IWT into a corporation abandoned as Ministry cites hardships that would be caused for government staff. Shan State submits proposal for international flights from Heho Proposal to connect Heho, near Inle Lake, with Chinese and Thai cities likely to be opposed by domestic airlines TRANSPORT NUMBER OF Q&A: EFR group chairman U Kyaw Lwin Oo THE WEEK Myanmar Transport Monitor met with EFR group chairman U Kyaw Lin Oo to discuss challenges and opportunities facing logistics companies in Myanmar. 684,568 passengers Minister claims Thilawa-Bago highway construction to begin next year About 684,568 passengers Declining demand strains Naypyitaw highway bus companies used the Yangon- Ministry of Construction removes Yangon bridge tolls on 1 April Naypyitaw route via bus in Daw Aung San Suu Kyi remarks on weakness of Sagaing transportation 2016, 70,000 fewer than in 2015 and about 115,000 Authorities to end private road toll collection in Tanintharyi Region less than in 2013, the year Buthidaung-Yathedaung bridge in Rakhine State opened of the SEA Games in Authorities announce Yangon water taxis will launch in May Naypyitaw. Upgrade works at six Yangon Circular Railway stations almost complete Improved trains coming for Mandalay-Myitkyina route The route was formerly an essential service after the Authorities plan crackdown on van owners illegally ferrying passenger capital was moved from Two firms shortlisted for Yangon bus passenger information system Yangon to Naypyitaw in Japan hands over first of three vessels for Rakhine State 2005. -

Environmentally Sustainable Food Security Programme (ESFSP)

Environmentally Sustainable Food Security Programme (ESFSP) Brief on the project “Support to the immediate rehabilitation of farming, coastal fisheries & aquaculture livelihoods in the cyclone Nargis-affected areas of Myanmar” (GCP/MYA/012/ITA) Demonstration plot of rice registered seed in Pyapon A. Outcomes and Outputs The project aims at sustainable improvements in household food production, nutritional status and income- generating activities among households and communities that comprise landless, marginal and small-scale farmers and fishers in the cyclone-affected townships of Bogale, Labutta and Pyapon. Output 1: Impoverished rural communities mobilized to benefit from improved agricultural support services 115 farmer field schools (FFS), 74 demonstration plots (DP) and 2 seed multiplication groups (SMG) have been implemented with 4 partners in 70 villages located in 20 village tracts, directly involving 7,200 farmers. Training covered to specific needs of each FFS group related to crop cycle management; conservation agriculture; integrated plant nutrient management systems; integrated pest management; postharvest technology for reducing pre- and post-harvest losses, and on-farm storage techniques; establishment and functioning of the rice bank system; crop intensification for rice-based cropping systems; and disaster risk management. Output 2: Enhanced long-term land productivity, reduced food insecurity and improved household nutritional status of impoverished farming communities This is mainly achieved through provision of seed of improved local varieties of rice, pulses and other crops; farm tools and equipment; transfer of improved technologies through the implementation of Farmer Field Schools (FFS); adoption of improved farming systems; formation and strengthening of farmers’ groups; establishment of revolving funds and matching contributions.