Interrogating the Interconnection Between Hijras and Indian Folk Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing Otherness: Uses of History and Mythology in Constructing Literary Representations of India’S Hijras

Writing Otherness: Uses of History and Mythology in Constructing Literary Representations of India’s Hijras A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Sarah E. Newport School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………….……………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Declaration……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Copyright Statement..………………………………………………………………………………………... 4 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………………... 5 Introduction: Mapping Identity: Constructing and (Re)Presenting Hijras Across Contexts………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 7 Chapter One: Hijras in Hindu Mythology and its Retellings……………………………….. 41 1. Hijras in Hindu Mythology and its Interpretations…………….……………….….. 41 2. Hindu Mythology and Hijras in Literary Representations……………….……… 53 3. Conclusion.………………………………………………………………………………...………... 97 Chapter Two: Slavery, Sexuality and Subjectivity: Literary Representations of Social Liminality Through Hijras and Eunuchs………………………………………………..... 99 1. Love, Lust and Lack: Interrogating Masculinity Through Third-Gender Identities in Habibi………………………………………..………………. 113 2. The Break Down of Privilege: Sexual Violence as Reform in The Impressionist….……………...……………………………………………………….……...… 124 3. Meeting the Other: Negotiating Hijra and Cisgender Interactions in Delhi: A Novel……...……………………………………………………..……………………….. 133 4. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………. 139 Chapter Three: Empires of the Mind: The Impact of -

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

Diversity for Peace: India's Cultural Spirituality

Cultural and Religious Studies, January 2017, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1-16 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2017.01.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Diversity for Peace: India’s Cultural Spirituality Indira Y. Junghare University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA In this age, the challenges of urbanization, industrialization, globalization, and mechanization have been eroding the stability of communities. Additionally, every existence, including humans, suffers from nature’s calamities and innate evolutionary changes—physically, mentally, and spiritually. India’s cultural tradition, being one of the oldest, has provided diverse worldviews, philosophies, and practices for peaceful-coexistence. Quite often, the multi-faceted tradition has used different methods of syncretism relevant to the socio-cultural conditions of the time. Ideologically correct, “perfect” peace is unattainable. However, it seems necessary to examine the core philosophical principles and practices India used to create unity in diversity, between people of diverse races, genders, and ethnicities. The paper briefly examines the nature of India’s cultural tradition in terms of its spirituality or philosophy of religion and its application to social constructs. Secondarily, the paper suggests consideration of the use of India’s spirituality based on ethics for peaceful living in the context of diversity of life. Keywords: diversity, ethnicity, ethics, peace, connectivity, interdependence, spiritual Introduction The world faces conflicts, violence, and wars in today’s world of globalization and due to diversity of peoples, regarding race, gender, age, class, birth-place, ethnicity, religion, and worldviews. In addition to suffering resulting from conflicts and violence arising from the issues of dominance and subservience, we have to deal with evolutionary changes. -

Mahabharata Tatparnirnaya

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Chapter XIX The episodes of Lakshagriha, Bhimasena's marriage with Hidimba, Killing Bakasura, Draupadi svayamwara, Pandavas settling down in Indraprastha are described in this chapter. The details of these episodes are well-known. Therefore the special points of religious and moral conduct highlights in Tatparya Nirnaya and its commentaries will be briefly stated here. Kanika's wrong advice to Duryodhana This chapter starts with instructions of Kanika an expert in the evil policies of politics to Duryodhana. This Kanika was also known as Kalinga. Probably he hailed from Kalinga region. He was a person if Bharadvaja gotra and an adviser to Shatrujna the king of Sauvira. He told Duryodhana that when the close relatives like brothers, parents, teachers, and friends are our enemies, we should talk sweet outwardly and plan for destroying them. Heretics, robbers, theives and poor persons should be employed to kill them by poison. Outwardly we should pretend to be religiously.Rituals, sacrifices etc should be performed. Taking people into confidence by these means we should hit our enemy when the time is ripe. In this way Kanika secretly advised Duryodhana to plan against Pandavas. Duryodhana approached his father Dhritarashtra and appealed to him to send out Pandavas to some other place. Initially Dhritarashtra said Pandavas are also my sons, they are well behaved, brave, they will add to the wealth and the reputation of our kingdom, and therefore, it is not proper to send them out. However, Duryodhana insisted that they should be sent out. He said he has mastered one hundred and thirty powerful hymns that will protect him from the enemies. -

Bahuchara Mata

Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies Volume 7 Number 1 Fall 2016 Article 4 2016 Bahuchara Mata Kunal Kanodia Columbia University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal Recommended Citation Kanodia, Kunal "Bahuchara Mata." Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 7, no. 1 (2016). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KUNAL KANODIA: BAHUCHARA MATA 87 KUNAL KANODIA is in his last year at Columbia University where he is pursuing a major in Human Rights with a concentration in Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies. His research interests lie in the intersectionality of identities of marginalized and subaltern communities in different social contexts. His interests include contemporary Hindi poetry, skydiving, cooking, Spanish literature and human rights advocacy. Kunal aspires to become a human rights lawyer someday. 88 IMW JOURNAL OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES VOL. 7:1 Kunal Kanodia BAHUCHARA MATA: LIBERATOR, PROTECTOR AND MOTHER OF HIJRAS IN GUJARAT INTRODUCTION The most prominent of myths surrounding the Hindu goddess Bahuchara Mata is that she belonged to the Charan caste, members of the Brahman class in Gujarat associated with divinity.1 As the narrative proceeds, one day Bahuchara Mata and her sisters were travelling when a looter named Bapiya attacked their caravan. This was considered a heinous sin.2 Bahuchara Mata cursed Bapiya with impotency and according to legend, self-immolated and cut off her own breasts. -

The Employment of Mythological and Literary Narratives in Identity Formation Among the Hijras of India

Vol. 4, no. 1 (2014), 21-39 | URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-114494 Narrating Identity: the Employment of Mythological and Literary Narratives in Identity Formation Among the Hijras of India JENNIFER UNG LOH* Abstract This article explores how the hijras and kinnars of India use mythological narratives in identity-formation. In contemporary India, the hijras are a minority group who are ostracised from mainstream society as a result of their non- heteronormative gender performances and anatomical presentations. Hijras suffer discrimination and marginalisation in their daily lives, forming their own social groups outside of natal families and kinship structures. Mythological and literary narratives play a significant role in explaining and legitimising behavioural patterns, ritual practices, and anatomical forms that are specific to hijras, and alleviating some of the stigma surrounding this identity. In this article, I focus on certain narratives that hijras employ in making sense of and giving meaning to their lives, including mythological stories concerning people of ambiguous gender and myths associated with Bahuchara Mata. I argue that these ontological narratives serve to bring hijra identity into being and play a crucial role in constructing and authenticating hijra identity in modern India. Keywords Hijras; kinnars; myth; narrativity; identity. Author affiliation Jennifer Ung Loh recently completed her PhD in the Department of the Study of Religions at SOAS, University of London (UK). Her research interests are gender, sexuality identity, -

Mainstreaming Third-Gender Healers: the Changing Percep- Tions of South Asian Hijras Pooja S

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Mainstreaming Third-Gender Healers: The Changing Percep- tions of South Asian Hijras Pooja S. Jagadish College of Arts and Science, Vanderbilt University Mainstreaming is the act of bringing public light to a population or issue, but it can have a deleterious impact on the individuals being discussed. Hijras comprise a third-gender group that has long had cultural and religious significance within South Asian societies. Described as being neither male nor female, hijras were once called upon for their religious powers to bless and curse. However, after the British rule and in the wake of more-recent media attention, the hijra identity has been scrutinized under a harsh Western gaze. It forces non-Western popula- tions to be viewed in terms of binaries, such as either male or female, and it classifies them by inapplicable Western terms. For example, categorizing a hijra as transgendered obfuscates the cultural significance that the term hijra conveys within their societies. Furthermore, media rep- resentations of hijras cause consumers to view themselves as more natural, while hijras become objectified as occupying a false identity. This has caused them to be pigeonholed within the very societies that once legitimated their existence and respected them for their powers. With their cultural practices being seen as outmoded, and their differences from Western people be- ing pointed out in the news and on television, hijras have faced significant discrimination and ridicule. After providing a discussion of relevant Western and non-Western concepts, I seek to describe hijras and the effects of mainstreaming on their lives. -

SHAKTI SHRINES TOUR - 06 Days 5 Nights / 6 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW

Tour Code : AKSR0151 Tour Type : FIT Package 1800 233 9008 SHAKTI SHRINES TOUR - www.akshartours.com 06 Days 5 Nights / 6 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW 1Country 8Cities 6Days 1Activities Accomodation Meal 01 Night Hotel Accomodation At Ambaji 5 Breckfast 01 Night Hotel Accomodation At Ahmadabad 5 Dinner 01 Night Hotel Accomodation At Rajkot 01 Night Hotel Accomodation At Bhavnagar 01 Night Hotel Accomodation At Vadodara Visa & Taxes 5% Gst Extra Highlights Accommodation on double sharing Breakfast and dinner at hotel Transfer and sightseeing by pvt vehicle as per program Applicable hotel taxes SIGHTSEEINGS OVERVIEW - Ambaji Temple - Modhera Temple - Umiya Mata’s Temple - Akshardham Temple - Chota Vaishnodevi Temple - Darshan of Chamunda Mate - Mahakali’s Temple - Champaner World Heritage Site SIGHTSEEINGS AMBAJI - Ambe mata Temple Ambaji is a census town in Banaskantha district in the state of Gujarat, India. It is known for its historical and mythological connections with sites of cultural heritage. In the holy temple of "Arasuri Ambaji", there is no image or statue of goddess the holy "Shree Visa Yantra" is worshiped as the main deity. No one can see the Yantra with naked eye. The photography of the Yantra is prohibited. The Arasuri Ambe Mata or Arbuda Mataji is kuldevi of Barad Parmaras. The one Parmar state is located near the ambaji town I.e.Danta and which also serves as capital of whole parmar clan. The original seat of Ambaji Mata is on Gabbar hilltop in the town. A large number of devotees visit the temple every year especially on Purnima days. A large mela on Bhadarvi poornima (full moon day) is held. -

The Idea of Gujarat History, Ethnography and Text

The Idea of Gujarat History, Ethnography and Text Edited by EDWARD SIMPSON and MARNA KAPADIA ~ Orient BlackSwan THE IDEA OF GUJARAT. ORIENT BLACKSWAN PRIVATE LIMITED Registered Office 3-6-752 Himayatnagar, Hyderabad 500 029 (A.P), India e-mail: [email protected] Other Offices Bangalore, Bhopal, Bhubaneshwar, Chennai, Ernakulam, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Jaipur, Kolkata, ~ . Luoknow, Mumba~ New Delbi, Patna © Orient Blackswan Private Limited First Published 2010 ISBN 978 81 2504113 9 Typeset by Le Studio Graphique, Gurgaon 122 001 in Dante MT Std 11/13 Maps cartographed by Sangam Books (India) Private Limited, Hyderabad Printed at Aegean Offset, Greater Noida Published by Orient Blackswan Private Limited 1 /24 Asaf Ali Road New Delhi 110 002 e-mail: [email protected] . The external boundary and coastline of India as depicted in the'maps in this book are neither correct nor authentic. CONTENTS List of Maps and Figures vii Acknowledgements IX Notes on the Contributors Xl A Note on the Language and Text xiii Introduction 1 The Parable of the Jakhs EDWARD SIMPSON ~\, , Gujarat in Maps 20 MARNA KAPADIA AND EDWARD SIMPSON L Caste in the Judicial Courts of Gujarat, 180(}-60 32 AMruTA SHODaAN L Alexander Forbes and the Making of a Regional History 50 MARNA KAPADIA 3. Making Sense of the History of Kutch 66 EDWARD SIMPSON 4. The Lives of Bahuchara Mata 84 SAMIRA SHEIKH 5. Reflections on Caste in Gujarat 100 HARALD TAMBs-LYCHE 6. The Politics of Land in Post-colonial Gujarat 120 NIKITA SUD 7. From Gandhi to Modi: Ahmedabad, 1915-2007 136 HOWARD SPODEK vi Contents S. -

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups on Kurukshetra

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups On Kurukshetra 1. On the fifteenth day of the Kurukshetra War, Krishna came up with a plan to kill this character. The previous night, this character retracted his Brahmastra [Bruh-mah-struh] when he was reprimanded for using a divine weapon on ordinary soldiers. After Bharadwaja ejaculated into a vessel when he saw a bathing Apsara, this character was born from the preserved semen. Because he promised that Arjuna would be the greatest archer in the world, this character demanded that (*) Ekalavya give him his right thumb. This character lays down his arms when Yudhishtira [Yoo-dhish-ti-ruh] lied to him that his son is dead, when in fact it was an elephant named Ashwatthama that was dead.. For 10 points, name this character who taught the Pandavas and Kauravas military arts. ANSWER: Dronacharya 2. On the second day of the Kurukshetra war, this character rescues Dhristadyumna [Dhrish-ta-dyoom-nuh] from Drona. After that, the forces of Kalinga attack this character, and they are almost all killed by this character, before Bhishma [Bhee-shmuh] rallies them. This character assumes the identity Vallabha when working as a cook in the Matsya kingdom during his 13th year of exile. During that year, this character ground the general (*) Kichaka’s body into a ball of flesh as revenge for him assaulting Draupadi. When they were kids, Arjuna was inspired to practice archery at night after seeing his brother, this character, eating in the dark. For 10 points, name the second-oldest Pandava. ANSWER: Bhima [Accept Vallabha before mention] 3. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

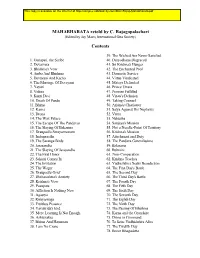

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Gods Or Aliens? Vimana and Other Wonders

Gods or Aliens? Vimana and other wonders Parama Karuna Devi Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2017 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved ISBN-13: 978-1720885047 ISBN-10: 1720885044 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Table of contents Introduction 1 History or fiction 11 Religion and mythology 15 Satanism and occultism 25 The perspective on Hinduism 33 The perspective of Hinduism 43 Dasyus and Daityas in Rig Veda 50 God in Hinduism 58 Individual Devas 71 Non-divine superhuman beings 83 Daityas, Danavas, Yakshas 92 Khasas 101 Khazaria 110 Askhenazi 117 Zarathustra 122 Gnosticism 137 Religion and science fiction 151 Sitchin on the Annunaki 161 Different perspectives 173 Speculations and fragments of truth 183 Ufology as a cultural trend 197 Aliens and technology in ancient cultures 213 Technology in Vedic India 223 Weapons in Vedic India 238 Vimanas 248 Vaimanika shastra 259 Conclusion 278 The author and the Research Center 282 Introduction First of all we need to clarify that we have no objections against the idea that some ancient civilizations, and particularly Vedic India, had some form of advanced technology, or contacts with non-human species or species from other worlds. In fact there are numerous genuine texts from the Indian tradition that contain data on this subject: the problem is that such texts are often incorrectly or inaccurately quoted by some authors to support theories that are opposite to the teachings explicitly presented in those same original texts.