4 the Lives of Bahuchara Mata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing Otherness: Uses of History and Mythology in Constructing Literary Representations of India’S Hijras

Writing Otherness: Uses of History and Mythology in Constructing Literary Representations of India’s Hijras A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Sarah E. Newport School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………….……………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Declaration……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Copyright Statement..………………………………………………………………………………………... 4 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………………... 5 Introduction: Mapping Identity: Constructing and (Re)Presenting Hijras Across Contexts………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 7 Chapter One: Hijras in Hindu Mythology and its Retellings……………………………….. 41 1. Hijras in Hindu Mythology and its Interpretations…………….……………….….. 41 2. Hindu Mythology and Hijras in Literary Representations……………….……… 53 3. Conclusion.………………………………………………………………………………...………... 97 Chapter Two: Slavery, Sexuality and Subjectivity: Literary Representations of Social Liminality Through Hijras and Eunuchs………………………………………………..... 99 1. Love, Lust and Lack: Interrogating Masculinity Through Third-Gender Identities in Habibi………………………………………..………………. 113 2. The Break Down of Privilege: Sexual Violence as Reform in The Impressionist….……………...……………………………………………………….……...… 124 3. Meeting the Other: Negotiating Hijra and Cisgender Interactions in Delhi: A Novel……...……………………………………………………..……………………….. 133 4. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………. 139 Chapter Three: Empires of the Mind: The Impact of -

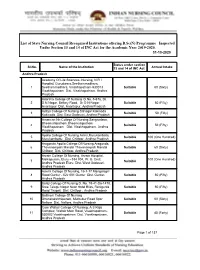

Programme Inspected Under Section 13 and 14 of INC Act for the Academic Year 2019-2020

List of State Nursing Council Recognised Institutions offering B.Sc(N) Programme Inspected Under Section 13 and 14 of INC Act for the Academic Year 2019-2020. 31-10-2020 Status under section Sl.No. Name of the Institution 13 and 14 of INC Act Annual Intake Andhra Pradesh Academy Of Life Sciences- Nursing, N R I Hospital, Gurudwara,Seethammadhara, 1 Seethammadhara, Visakhapatnam-530013 Suitable 60 (Sixty) Visakhapatnam Dist. Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh Adarsha College Of Nursing D.No. 5-67a, Dr. 2 D.N.Nagar, Bellary Road, Dr D N Nagar Suitable 50 (Fifty) Anantapur Dist. Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh Aditya College Of Nursing Srinagar Kakinada 3 Suitable 50 (Fifty) Kakinada Dist. East Godavari, Andhra Pradesh American Nri College Of Nursing Sangivalasa, Bheemunipatnam Bheemunipatnam 4 Suitable 50 (Fifty) Visakhapatnam Dist. Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh Apollo College Of Nursing Aimsr,Murukambattu 5 Suitable 100 (One Hundred) Murukambattu Dist. Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh Aragonda Apollo College Of Nursing Aragonda, 6 Thavanampalli Mandal Thavanampalli Mandal Suitable 60 (Sixty) Chittoor Dist. Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh Asram College Of Nursing, Asram Hospital, Malkapuram, Eluru - 534 004, W. G. Distt. 100 (One Hundred) 7 Suitable Andhra Pradesh Eluru Dist. West Godavari, Andhra Pradesh Aswini College Of Nursing, 15-1-17 Mangalagiri 8 Road Guntur - 522 001 Guntur Dist. Guntur, Suitable 50 (Fifty) Andhra Pradesh Balaji College Of Nursing D. No. 19-41-S6-1478, 9 Sree Telugu Nagar Near Hotel Bliss, Renigunta Suitable 50 (Fifty) Road Tirupati Dist. Chittoor , Andhra Pradesh Bollineni College Of Nursing 10 Dhanalakshmipuram, Muthukur Road Spsr Suitable 60 (Sixty) Nellore Dist. Nellore, Andhra Pradesh Care Waltair College Of Nursing, A S Raja Complex, Waltair Main Road, Visakhapatnam- 11 Suitable 40 (Forty) 530002 Visakhapatnam Dist. -

Diversity for Peace: India's Cultural Spirituality

Cultural and Religious Studies, January 2017, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1-16 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2017.01.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Diversity for Peace: India’s Cultural Spirituality Indira Y. Junghare University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA In this age, the challenges of urbanization, industrialization, globalization, and mechanization have been eroding the stability of communities. Additionally, every existence, including humans, suffers from nature’s calamities and innate evolutionary changes—physically, mentally, and spiritually. India’s cultural tradition, being one of the oldest, has provided diverse worldviews, philosophies, and practices for peaceful-coexistence. Quite often, the multi-faceted tradition has used different methods of syncretism relevant to the socio-cultural conditions of the time. Ideologically correct, “perfect” peace is unattainable. However, it seems necessary to examine the core philosophical principles and practices India used to create unity in diversity, between people of diverse races, genders, and ethnicities. The paper briefly examines the nature of India’s cultural tradition in terms of its spirituality or philosophy of religion and its application to social constructs. Secondarily, the paper suggests consideration of the use of India’s spirituality based on ethics for peaceful living in the context of diversity of life. Keywords: diversity, ethnicity, ethics, peace, connectivity, interdependence, spiritual Introduction The world faces conflicts, violence, and wars in today’s world of globalization and due to diversity of peoples, regarding race, gender, age, class, birth-place, ethnicity, religion, and worldviews. In addition to suffering resulting from conflicts and violence arising from the issues of dominance and subservience, we have to deal with evolutionary changes. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Kultura I Historia Nr 35 / 2019 (1)

Kultura i Historia Nr 35 / 2019 (1) „Inna i Inny” – o światopoglądach, stylach życia, odmienności płciowej oraz…? Wydawca: Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej Redakcja: Instytut Kulturoznawstwa, Plac Marii Curie- Skłodowskiej 4, 20-031 Lublin. „Stara Humanistyka”, piętro III, pok. 331/332. Redaktor Naczelny: dr hab. Andrzej Radomski, Prof. UMCS; Redaktor naukowy: Sidey Myoo; Redaktor tematyczny: Kamil Stępień; Redaktorzy techniczni: Marta Kostrzewa, Adrian Mróz; Redaktor językowy: Denis Gornichar; Korekta języka polskiego: Katarzyna Łęk; Redaktorami prowadzącymi numerów od 31 są Andrzej Radomski i Sidey Myoo Współpraca: Anna Shvets, Piotr Niewęgłowski, Jarosław Przychoda, dr hab. Andrzej Stępnik, Piotr Wojcieszuk, dr hab. Marek Woźniak Autor logo: mgr Sebastian Zonik Spis Treści DUCHOWE SPOTKANIA I ROZTERKI Magdalena Miryn: Ruch non-duality w Polsce. Kulturoznawcza analiza nowego ruchu religijnego. .......................................................................................................... 1 Joanna Gołębiewska: Pamiętnik „Trzy po trzy” Aleksandra Fredry – dzieło literackie czy źródło historyczne?............................................................................................... 12 Magdalena Karlikowska-Pąsiek: Światopogląd księcia Lwa Myszkina a proces komunikacji z innymi bohaterami. Sceniczna adaptacja Idioty w reżyserii Norberta Rakowskiego..................................................................................................... 25 Włodzimierz Borysiak: Dramaturgia A. Czechowa na scenach polskich -

Bhadrakali - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

בהאדראקאלי http://www.tripi.co.il/ShowItem.action?item=948 بهادراكالي http://ar.hotels.com/de1685423/%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84-%D9%83%D8%A 7%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AF%D9%88-%D9%85%D8%B9%D8%A8%D8%AF-%D8 %A8%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%8A-%D8%A7% D9%84%D9%81%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%82-%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A8 Bhadrakali - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhadrakali Bhadrakali From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bhadrak ālī (Sanskrit: भकाली , Tamil: பரகாள, Telugu: wq, Malayalam: , Kannada: ಭದಾ, Kodava: Bhadrak ālī (Good Kali, Mahamaya Kali) ಭದಾ) (literally " Good Kali, ") [1] is a Hindu goddess popular in Southern India. She is one of the fierce forms of the Great Goddess (Devi) mentioned in the Devi Mahatmyam. Bhadrakali is the popular form of Devi worshipped in Kerala as Sri Bhadrakali and Kariam Kali Murti Devi. In Kerala she is seen as the auspicious and fortunate form of Kali who protects the good. It is believed that Bhadrak āli was a local deity that was assimilated into the mainstream Hinduism, particularly into Shaiva mythology. She is represented with three eyes, and four, twelve or eighteen hands. She carries a number of weapons, with flames flowing from her head, and a small tusk protruding from her mouth. Her worship is also associated with the Bhadrakali worshipped by the Trimurti – the male Tantric tradition of the Matrikas as well as the tradition of the Trinity in the North Indian Basohli style. -

Hospital Master

S.No HOSPITALNAME STREET CITYDESC STATEDESC PINCODE 1 Highway Hospital Dev Ashish Jeen Hath Naka, Maarathon Circle Mumbai and Maharashtra 400601 Suburb 2 PADMAVATI MATERNITY AND 215/216- Oswal Oronote, 2nd Thane Maharashtra 401105 NURSING HOME 3 Jai Kamal Eye Hospital Opp Sandhu Colony G.T.Road, Chheharta, Amritsar Amritsar Punjab 143001 4 APOLLO SPECIALITY HOSPITAL Chennai By-Pass Road, Tiruchy TamilNadu 620010 5 Khanna Hospital C2/396,Janakpuri New Delhi Delhi 110058 6 B.M Gupta Nursing Home H-11-15 Arya Samaj Road,Uttam Nagar New Delhi Delhi 110059 Pvt.Ltd. 7 Divakar Global Hospital No. 220, Second Phase, J.P.Nagar, Bengaluru Karnataka 560078 8 Anmay Eye Hospital - Dr Off. C.G. Road , Nr. President Hotel,Opp. Mahalya Ahmedabad Gujarat 380009 Raminder Singh Building, Navrangpura 9 Tilak Hospital Near Ramlila Ground,Gurgaon Road,Pataudi,Gurgaon-Gurugram Haryana 122503 122503 10 GLOBAL 5 Health Care F-2, D-2, Sector9, Main Road, Vashi, Navi Mumbai Mumbai and Maharashtra 400703 Suburb 11 S B Eye Care Hospital Anmol Nagar, Old Tanda Road, Tanda By-Pass, Hoshiarpur Punjab 146001 Hoshiarpur 12 Dhir Eye Hospital Old Court Road Rajpura Punjab 140401 13 Bilal Hospital Icu Ryal Garden,A wing,Nr.Shimla Thane Maharashtra 401201 Park,Kausa,Mumbra,Thane 14 Renuka Eye Institute 25/3,Jessre road,Dakbanglow Kolkata West Bengal 700127 More,Rathala,Barsat,Kolkatta 15 Pardi Hospital Nh No-8, Killa Pardi, Opp. Renbasera HotelPardi Valsad Gujarat 396001 16 Jagat Hospital Raibaraily Road, Naka Chungi, Faizabad Faizabad Uttar Pradesh 224001 17 SANT DNYANESHWAR Sant Nagar, Plot no-1/1, Sec No-4, Moshi Pune Maharashtra 412105 HOSPITAL PRIVATE LIMITED Pradhikaran,Pune-Nashik Highway, Spine Road 18 Lotus Hospital #389/3, Prem Nagar, Mata Road-122001 Gurugram Haryana 122001 19 Samyak Hospital BM-7 East Shalimar Bagh New Delhi Delhi 110088 20 Bristlecone Hospitals Pvt. -

Gujarat Cotton Crop Estimate 2019 - 2020

GUJARAT COTTON CROP ESTIMATE 2019 - 2020 GUJARAT - COTTON AREA PRODUCTION YIELD 2018 - 2019 2019-2020 Area in Yield per Yield Crop in 170 Area in lakh Crop in 170 Kgs Zone lakh hectare in Kg/Ha Kgs Bales hectare Bales hectare kgs Kutch 0.563 825.00 2,73,221 0.605 1008.21 3,58,804 Saurashtra 19.298 447.88 50,84,224 18.890 703.55 78,17,700 North Gujarat 3.768 575.84 12,76,340 3.538 429.20 8,93,249 Main Line 3.492 749.92 15,40,429 3.651 756.43 16,24,549 Total 27.121 512.38 81,74,214 26.684 681.32 1,06,94,302 Note: Average GOT (Lint outturn) is taken as 34% Changes from Previous Year ZONE Area Yield Crop Lakh Hectare % Kgs/Ha % 170 kg Bales % Kutch 0.042 7.46% 183.21 22.21% 85,583 31.32% Saurashtra -0.408 -2.11% 255.67 57.08% 27,33,476 53.76% North Gujarat -0.23 -6.10% -146.64 -25.47% -3,83,091 -30.01% Main Line 0.159 4.55% 6.51 0.87% 84,120 5.46% Total -0.437 -1.61% 168.94 32.97% 25,20,088 30.83% Gujarat cotton crop yield is expected to rise by 32.97% and crop is expected to increase by 30.83% Inspite of excess and untimely rains at many places,Gujarat is poised to produce a very large cotton crop SAURASHTRA Area in Yield Crop in District Hectare Kapas 170 Kgs Bales Lint Kg/Ha Maund/Bigha Surendranagar 3,55,100 546.312 13.00 11,41,149 Rajkot 2,64,400 714.408 17.00 11,11,115 Jamnagar 1,66,500 756.432 18.00 7,40,858 Porbandar 9,400 756.432 18.00 41,826 Junagadh 74,900 756.432 18.00 3,33,275 Amreli 4,02,900 756.432 18.00 17,92,744 Bhavnagar 2,37,800 756.432 18.00 10,58,115 Morbi 1,86,200 630.360 15.00 6,90,430 Botad 1,63,900 798.456 19.00 7,69,806 Gir Somnath 17,100 924.528 22.00 92,997 Devbhumi Dwarka 10,800 714.408 17.00 45,386 TOTAL 18,89,000 703.552 16.74 78,17,700 1 Bigha = 16 Guntha, 1 Hectare= 6.18 Bigha, 1 Maund= 20 Kg Saurashtra sowing area reduced by 2.11%, estimated yield increase 57.08%, estimated Crop increase by 53.76%. -

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional -

Bahuchara Mata

Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies Volume 7 Number 1 Fall 2016 Article 4 2016 Bahuchara Mata Kunal Kanodia Columbia University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal Recommended Citation Kanodia, Kunal "Bahuchara Mata." Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 7, no. 1 (2016). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KUNAL KANODIA: BAHUCHARA MATA 87 KUNAL KANODIA is in his last year at Columbia University where he is pursuing a major in Human Rights with a concentration in Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies. His research interests lie in the intersectionality of identities of marginalized and subaltern communities in different social contexts. His interests include contemporary Hindi poetry, skydiving, cooking, Spanish literature and human rights advocacy. Kunal aspires to become a human rights lawyer someday. 88 IMW JOURNAL OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES VOL. 7:1 Kunal Kanodia BAHUCHARA MATA: LIBERATOR, PROTECTOR AND MOTHER OF HIJRAS IN GUJARAT INTRODUCTION The most prominent of myths surrounding the Hindu goddess Bahuchara Mata is that she belonged to the Charan caste, members of the Brahman class in Gujarat associated with divinity.1 As the narrative proceeds, one day Bahuchara Mata and her sisters were travelling when a looter named Bapiya attacked their caravan. This was considered a heinous sin.2 Bahuchara Mata cursed Bapiya with impotency and according to legend, self-immolated and cut off her own breasts. -

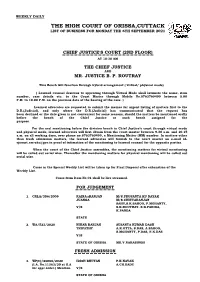

Causelistgenerate Report

WEEKLY DAILY THE HIGH COURT OF ORISSA,CUTTACK LIST OF BUSINESS FOR MONDAY THE 6TH SEPTEMBER 2021 CHIEF JUSTICE'S COURT (2ND FLOOR) AT 10:30 AM THE CHIEF JUSTICE AND MR. JUSTICE B. P. ROUTRAY This Bench will function through hybrid arrangement ( virtual/ physical mode). ( Learned counsel desirous to appearing through Virtual Mode shall intimate the name, item number, case details etc. to the Court Master through Mobile No.8763760499 between 8.00 P.M. to 10.00 P.M. on the previous date of the hearing of the case. ) Learned advocates are requested to submit the memos for urgent listing of matters first to the D.R.(Judicial), and only where the D.R.(Judicial) has communicated that the request has been declined or the date given is not convenient for some reasons, should the matters be mentioned orally before the bench of the Chief Justice or such bench assigned for the purpose. For the oral mentioning before the division bench in Chief Justice’s court through virtual mode and physical mode, learned advocates will first obtain from the court master between 9.30 a.m. and 10.15 a.m. on all working days, over phone no.8763760499, a Mentioning Matter (MM) number. In matters other than fresh admission matters, the learned advocates will furnish to the court master on e-mail id- [email protected] proof of intimation of the mentioning to learned counsel for the opposite parties. When the court of the Chief Justice assembles, the mentioning matters for virtual mentioning will be called out serial wise. -

Rainfall in Mm) Sr

State Emergency Operation Centre,Revenue Department, Gandhinagar Rainfall Report 31/10/2018 (Rainfall in mm) Sr. District/ Avg Rain Rains till Rain During Total % Against Avg Rain Rains till Rain During Total % Against No Sr.No. District/ Taluka Taluka (1988-2017) Yesterday last 24 Hrs. Rainfall Avg Rain (1988-2017) Yesterday last 24 Hrs. Rainfall Avg Rain . 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 KUTCH NORTH GUJARAT 1 Kutch 4 Mahesana 1 Abdasa 390 53 0 53 13.61 1 Becharaji 659 294 0 294 44.64 2 Anjar 434 231 0 231 53.28 2 Jotana 753 139 0 139 18.45 3 Bhachau 441 103 0 103 23.36 3 Kadi 814 258 0 258 31.71 4 Bhuj 376 83 0 83 22.08 4 Kheralu 727 207 0 207 28.47 5 Gandhidham 403 264 0 264 65.54 5 Mahesana 760 288 0 288 37.90 6 Lakhpat 349 12 0 12 3.44 6 Satlasana 769 504 0 504 65.55 7 Mandvi(K) 434 118 0 118 27.22 7 Unjha 743 239 0 239 32.18 8 Mundra 477 145 0 145 30.40 8 Vadnagar 694 307 0 307 44.21 9 Nakhatrana 406 70 0 70 17.22 9 Vijapur 826 370 0 370 44.80 10 Rapar 460 26 0 26 5.65 10 Visnagar 689 195 0 195 28.32 Dist. Avg. 417 111 0 111 26.51 Dist. Avg. 743 280 0 280 37.70 KUTCH REGION 417 111 0 111 26.51 5 Sabarkantha 1 Himatanagar 838 902 0 902 107.60 NORTH GUJARAT 2 Idar 960 763 0 763 79.45 2 Patan 3 Khedbrahma 843 502 0 502 59.56 1 Chanasma 525 103 0 103 19.60 4 Posina 833 503 0 503 60.38 2 Harij 577 173 0 173 29.97 5 Prantij 832 415 0 415 49.86 3 Patan 685 164 0 164 23.93 6 Talod 804 418 0 418 51.97 4 Radhanpur 626 190 0 190 30.36 7 Vadali 877 556 0 556 63.38 5 Sami 537 168 0 168 31.26 8 Vijaynagar 835 673 0 673 80.58 6 Santalpur 478 154 0 154 32.22 Dist.