Antrocom Journal of Anthropology ANTROCOM Journal Homepage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book Kamadeva the God of Desire Pdf Free Download

KAMADEVA THE GOD OF DESIRE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anuja Chandramouli | 336 pages | 01 Sep 2015 | Rupa & Co | 9788129134592 | English | New Delhi, India Kamadeva the God of Desire PDF Book Oh how about including VHP in all of this. Brahma advises that Parvati should seduce Shiva since their offspring would be able to defeat Taraka. So from that perspective, this book gives Kamadeva a point of view in the epic tradition. Post a Comment. As a lover of ASOIAF series, it was hard to notice that even a book of that level of complexity was written in a very simple language but this one was one hell of a complex bundle of difficult sentences and words. We respect your privacy and will never share your email address with any person or organization. Kamadeva was created by Lord Brahma in order to introduce love among the people, and also for the creation of people. Preview — Kamadeva by Anuja Chandramouli. Why We Say Namaste. Jul 20, Urvashi rated it it was ok. I will definitely order again from Exotic India with full confidence. There are different versions of his story found in the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and the Puranas, among other texts. This makes the tale dragging and boring, to put it bluntly. Yogapedia explains Kamadeva Hindu mythology offers several different versions of Kamadeva's origins. Could she please write more such. Best friends with Indra, the King of the Gods, tutor to the Apsaras in the art of lovemaking, Kamadeva lives a dream life in the magnificent Kingdom of Amaravathi-until danger strikes when he incurs the wrath of Shiva because of a preordained curse. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R

THE PALGRAVE MACMILLAN ANIMAL ETHICS SERIES Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series Editors Andrew Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK Priscilla N. Cohn Pennsylvania State University Villanova, PA, USA Associate Editor Clair Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. Tis series will explore the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifcally, the Series will: • provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals • publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars; • produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in character or have multidisciplinary relevance. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14421 Kenneth R. Valpey Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies Oxford, UK Te Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series ISBN 978-3-030-28407-7 ISBN 978-3-030-28408-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28408-4 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

An Analysis of Tantric Practices at Kamakhya and Tarapith

International Journal of Applied Research 2018; 4(4): 39-41 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 Re-examining the cult of the feminine: An analysis of IJAR 2018; 4(4): 39-41 www.allresearchjournal.com tantric practices at Kamakhya and Tarapith Received: 15-02-2018 Accepted: 17-03-2018 Dr. Chandni Sengupta Dr Chandni Sengupta Assistant Professor, Department of History, Amity Abstract School of Liberal Arts, Amity Tantricism is inextricably inter-linked with the cult of the feminine. Tantric rituals exalt the female University Haryana, Haryana, deity and celebrate the power (Shakti) of the female form of divinity. In India, alongside the Vedic India system of worship, Tantricism has co-existed for centuries. There are references to the Tantric tradition in the epics; similar references have also been found in the Indus Valley civilization. There are many shakti peeths in India but only a few are associated with Tantricism. This article aims to explore the Tantric rituals at the temples of Kamakhya in Assam and Tarapith in West Bengal, in order to establish the significance of the Tantric tradition even in the 21st century. Keywords: tantricism, tantra, ritual, goddess, Shakti, Devi, cult, practices Introduction In India, since the ancient time, two distinct and parallel forms of worship have existed- Vedic and Non-Vedic. Kallukabhatta, the first scholar who presented an exhaustive interpretation of the Manusmriti, made a clear distinction between two branches of Indian thought. He divided Indian wisdom into Vedic and Tantric [1]. The former was based on a male-centric social order, while the latter was based on the principles of matriarchy and consequently the notions of fertility. -

Ch. 3 MALE DEITIES I. Worship of Vishnu and Its Forms in Goa Vishnu

Ch. 3 MALE DEITIES I. Worship of Vishnu and its forms in Goa Vishnu is believed to be the Preserver God in the Hindu pantheon today. In the Vedic text he is known by the names like Urugai, Urukram 'which means wide going and wide striding respectively'^. In the Rgvedic text he is also referred by the names like Varat who is none other than says N. P. Joshi^. In the Rgvedhe occupies a subordinate position and is mentioned only in six hymns'*. In the Rgvedic text he is solar deity associated with days and seasons'. References to the worship of early form of Vishnu in India are found in inscribed on the pillar at Vidisha. During the second to first century BCE a Greek by name Heliodorus had erected a pillar in Vidisha in the honor of Vasudev^. This shows the popularity of Bhagvatism which made a Greek convert himself to the fold In the Purans he is referred to as Shripati or the husband oiLakshmi^, God of Vanmala ^ (wearer of necklace of wild flowers), Pundarikaksh, (lotus eyed)'". A seal showing a Kushan chief standing in a respectful pose before the four armed God holding a wheel, mace a ring like object and a globular object observed by Cunningham appears to be one of the early representations of Vishnu". 1. Vishnu and its attributes Vishnu is identified with three basic weapons which he holds in his hands. The conch, the disc and the mace or the Shankh. Chakr and Gadha. A. Shankh Termed as Panchjany Shankh^^ the conch was as also an essential element of Vishnu's identity. -

Bhadrakali - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

בהאדראקאלי http://www.tripi.co.il/ShowItem.action?item=948 بهادراكالي http://ar.hotels.com/de1685423/%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84-%D9%83%D8%A 7%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AF%D9%88-%D9%85%D8%B9%D8%A8%D8%AF-%D8 %A8%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%8A-%D8%A7% D9%84%D9%81%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%82-%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A8 Bhadrakali - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhadrakali Bhadrakali From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bhadrak ālī (Sanskrit: भकाली , Tamil: பரகாள, Telugu: wq, Malayalam: , Kannada: ಭದಾ, Kodava: Bhadrak ālī (Good Kali, Mahamaya Kali) ಭದಾ) (literally " Good Kali, ") [1] is a Hindu goddess popular in Southern India. She is one of the fierce forms of the Great Goddess (Devi) mentioned in the Devi Mahatmyam. Bhadrakali is the popular form of Devi worshipped in Kerala as Sri Bhadrakali and Kariam Kali Murti Devi. In Kerala she is seen as the auspicious and fortunate form of Kali who protects the good. It is believed that Bhadrak āli was a local deity that was assimilated into the mainstream Hinduism, particularly into Shaiva mythology. She is represented with three eyes, and four, twelve or eighteen hands. She carries a number of weapons, with flames flowing from her head, and a small tusk protruding from her mouth. Her worship is also associated with the Bhadrakali worshipped by the Trimurti – the male Tantric tradition of the Matrikas as well as the tradition of the Trinity in the North Indian Basohli style. -

Hospital Master

S.No HOSPITALNAME STREET CITYDESC STATEDESC PINCODE 1 Highway Hospital Dev Ashish Jeen Hath Naka, Maarathon Circle Mumbai and Maharashtra 400601 Suburb 2 PADMAVATI MATERNITY AND 215/216- Oswal Oronote, 2nd Thane Maharashtra 401105 NURSING HOME 3 Jai Kamal Eye Hospital Opp Sandhu Colony G.T.Road, Chheharta, Amritsar Amritsar Punjab 143001 4 APOLLO SPECIALITY HOSPITAL Chennai By-Pass Road, Tiruchy TamilNadu 620010 5 Khanna Hospital C2/396,Janakpuri New Delhi Delhi 110058 6 B.M Gupta Nursing Home H-11-15 Arya Samaj Road,Uttam Nagar New Delhi Delhi 110059 Pvt.Ltd. 7 Divakar Global Hospital No. 220, Second Phase, J.P.Nagar, Bengaluru Karnataka 560078 8 Anmay Eye Hospital - Dr Off. C.G. Road , Nr. President Hotel,Opp. Mahalya Ahmedabad Gujarat 380009 Raminder Singh Building, Navrangpura 9 Tilak Hospital Near Ramlila Ground,Gurgaon Road,Pataudi,Gurgaon-Gurugram Haryana 122503 122503 10 GLOBAL 5 Health Care F-2, D-2, Sector9, Main Road, Vashi, Navi Mumbai Mumbai and Maharashtra 400703 Suburb 11 S B Eye Care Hospital Anmol Nagar, Old Tanda Road, Tanda By-Pass, Hoshiarpur Punjab 146001 Hoshiarpur 12 Dhir Eye Hospital Old Court Road Rajpura Punjab 140401 13 Bilal Hospital Icu Ryal Garden,A wing,Nr.Shimla Thane Maharashtra 401201 Park,Kausa,Mumbra,Thane 14 Renuka Eye Institute 25/3,Jessre road,Dakbanglow Kolkata West Bengal 700127 More,Rathala,Barsat,Kolkatta 15 Pardi Hospital Nh No-8, Killa Pardi, Opp. Renbasera HotelPardi Valsad Gujarat 396001 16 Jagat Hospital Raibaraily Road, Naka Chungi, Faizabad Faizabad Uttar Pradesh 224001 17 SANT DNYANESHWAR Sant Nagar, Plot no-1/1, Sec No-4, Moshi Pune Maharashtra 412105 HOSPITAL PRIVATE LIMITED Pradhikaran,Pune-Nashik Highway, Spine Road 18 Lotus Hospital #389/3, Prem Nagar, Mata Road-122001 Gurugram Haryana 122001 19 Samyak Hospital BM-7 East Shalimar Bagh New Delhi Delhi 110088 20 Bristlecone Hospitals Pvt. -

Ambubachi Mela in Assam's Kamakhya Temple

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 1 I JAN. – MARCH 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Ambubachi Mela in Assam’s Kamakhya Temple: A Critical Analysis Sangeeta Das Research Scholar Centre for the Study of Social Systems, School of Social Sciences Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi – 110067 Received Dec. 29, 2017 Accepted Feb. 01, 2018 ABSTRACT With globalization, religion is mixing up with capitalism and consumerism. Old religious observances are finding new modern uses. Ambubachi, celebration of goddess menstruation in Assam’s Kamakhya temple has also undergone significant changes overtime. An analysis of the festival reveals its dichotomous nature. On the one hand, it celebrates menstruation and on the other hand, retains the tradition of menstrual seclusion even for Goddess Kamakhya. The strict rules and taboos that used to be a part of this festival have now become flexible. The temple premise during the period of Ambubachi has also turned more into a commercial site. Thus, although devotees continue to throng Kamakhya temple during Ambubachi mela, yet study reveals that the festival has certain attributes that deserve sincere academic scrutiny. Keywords: Ambubachi, Menstruation, Goddess, Religion. KAMAKHYA TEMPLE: A HISTORCAL ANALYSIS The Kamakhya temple is the famous Ahaar month in Assamese calendar. It is known as pilgrimage spot for the Hindus and Tantric the menses period for Goddess Kamakhya. What is worshipper located on the Nilachala hill in the worshipped at Kamakhya during Ambubachi Mela Guwahati city of the Eastern Indian state of Assam. is not an image of the Goddess but rather a The uniqueness of the temple is that there is no process: a formal process of menstruation. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Causelistgenerate Report

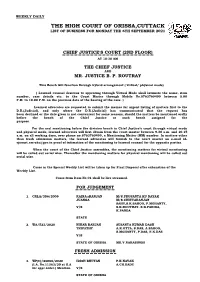

WEEKLY DAILY THE HIGH COURT OF ORISSA,CUTTACK LIST OF BUSINESS FOR MONDAY THE 6TH SEPTEMBER 2021 CHIEF JUSTICE'S COURT (2ND FLOOR) AT 10:30 AM THE CHIEF JUSTICE AND MR. JUSTICE B. P. ROUTRAY This Bench will function through hybrid arrangement ( virtual/ physical mode). ( Learned counsel desirous to appearing through Virtual Mode shall intimate the name, item number, case details etc. to the Court Master through Mobile No.8763760499 between 8.00 P.M. to 10.00 P.M. on the previous date of the hearing of the case. ) Learned advocates are requested to submit the memos for urgent listing of matters first to the D.R.(Judicial), and only where the D.R.(Judicial) has communicated that the request has been declined or the date given is not convenient for some reasons, should the matters be mentioned orally before the bench of the Chief Justice or such bench assigned for the purpose. For the oral mentioning before the division bench in Chief Justice’s court through virtual mode and physical mode, learned advocates will first obtain from the court master between 9.30 a.m. and 10.15 a.m. on all working days, over phone no.8763760499, a Mentioning Matter (MM) number. In matters other than fresh admission matters, the learned advocates will furnish to the court master on e-mail id- [email protected] proof of intimation of the mentioning to learned counsel for the opposite parties. When the court of the Chief Justice assembles, the mentioning matters for virtual mentioning will be called out serial wise. -

List of Candidates Called for Preliminary Examination for Direct Recruitment of Grade-I Officers in Assam Judicial Service

LIST OF CANDIDATES CALLED FOR PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION FOR DIRECT RECRUITMENT OF GRADE-I OFFICERS IN ASSAM JUDICIAL SERVICE. [ Candidature is subject to fulfilment of eligibility criteria prescribed by the Rules ] Sl No Name of the Category Roll No Issue No Present Address Candidate 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 AAMIR AKHTAR General 0001 3244 C-119, Reids Line, Delhi University, Delhi-7 2 ABDUL AWAL DEWAN General 0002 3245 Maherban Path, P.O.& P/S Hatigaon, Dist: Kamrup, Assam 3 ABDUL HAI LASKAR General 0003 3246 Madurband (Kandigram), PO & PS- Silchar, Dist- Cachar, Assam, Pin-788001 4 ABDUL MANNAN SARKAR General 0004 3247 Bilasipara, W/No.7, P.O. & P.S. Bilasipara, Dist. Dhubri, Assam 5 ABDUL RAKIB BARLASKAR General 0005 3248 Vill: Bahadurpur, P.O. Rongpur PT-II, Dist. Cachar, Assam, Pin 788009 6 ABDUS SABUR AKAND General 0006 3249 Bishnujyoti Path, Shanaghar, Hatigaon, Dist Kamrup (M) ,Pin-781038, Assam 7 ABHIJIT BHATTACHARYA General 0007 3250 Purbashree Apartment, Flat No. 2/3, Borthakur Mill Road, Ulubari, Guwahati-781007 8 ABHIJIT BHATTACHARYA General 0008 3251 53, LAMB Road, Opp. Ugratara Temple, Uzan Bazar, Guwahati781001 9 ABHIJIT GHOSH OBC 0009 3252 Jyoti Nagar, Bongal Pukhuri, PO & PS- Jorhat, Dist. Jorhat , Assam, 10 ABIDUR RAHMAN General 0010 3253 Sibsagar Bar Association, P.O. Sibsagar, Dist. Sibsagar, Assam, Pin - 785640. 11 ABU BAKKAR SIDDIQUE General 0011 3254 R/O House No.7, Bishnujyoti Path(West), Natbama,(Near Pipe Line), P.O. Hatigaon, Guwahati-781038 12 ABUBAKKAR SIDDIQUE General 0012 3255 P.D.Chaliha Road, H. No.-11, Ground Floor, Hedayetpur, P/S Latasil, P.O. -

THE HINDU VIEW on MENSTRUATION “A Woman Is the Creator of the Universe, the Universe Is Her Form

THE HINDU VIEW ON MENSTRUATION ªA woman is the Creator of the Universe, the Universe is her form. A woman is the foundation of the world.... There is no prayer equal to a woman, There is not, nor has been, nor will be any yoga to compare with a woman, no mystical formula nor asceticism to match a womanº (Shakti-Sangama Tantra II.52) There have been so many (sometimes untrue, misleading) interpolations of our Vedic Shastras, especially from the West, and by unqualified commentators about this highly sensitive topic, that we now feel obliged to comment about it and right the wrongs that have truly marred our understanding of this extremely delicate and misunderstood subject. In our shastras there is quite a lot of information on this matter but one should remember that one has to view this information with a modernistic mentality rather than a Neanderthal mentality. DO NOTE:- In this article we tried to cover as much on Menstruation as possible. This very lengthy article is rather thought-provoking and is not intended to create further questions, but rather to view the topic from different perspectives. This is certainly a hotly debated issue that excited and provoked many arguments concerning the relationship between religion, culture and menstruation. In an effort to assist humanity, Dipika©s aim is to share this sacred knowledge regarding this controversial subject. We shall be providing views from a Medical, Scientific, Religious, a ªCommon Senseº point of view, and finally F.A.Q.©s CONTENTS IN THIS ARTICLE Page 1:- Introduction Page 2:- The Medical point of view on Menstruation, The Scientific point of view on Menstruation Page 3:- The Religious view on Menstruation, Positive Information on Menstruation.