The Rebbe and President Reagan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

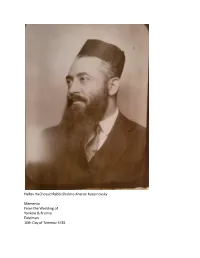

Shlomo Aharon Kazarnovsky 1

HaRav HaChossid Rabbi Sholmo Aharon Kazarnovsky Memento From the Wedding of Yankele & Frumie Eidelman 10th Day of Tammuz 5781 ב״ה We thankfully acknowledge* the kindness that Hashem has granted us. Due to His great kindness, we merited the merit of the marriage of our children, the groom Yankele and his bride, Frumie. Our thanks and our blessings are extended to the members of our family, our friends, and our associates who came from near and far to join our celebration and bless our children with the blessing of Mazal Tov, that they should be granted lives of good fortune in both material and spiritual matters. As a heartfelt expression of our gratitude to all those participating in our celebration — based on the practice of the Rebbe Rayatz at the wedding of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin of giving out a teshurah — we would like to offer our special gift: a compilation about the great-grandfather of the bride, HaRav .Karzarnovsky ע״ה HaChossid Reb Shlomo Aharon May Hashem who is Good bless you and all the members of Anash, together with all our brethren, the Jewish people, with abundant blessings in both material and spiritual matters, including the greatest blessing, that we proceed from this celebration, “crowned with eternal joy,” to the ultimate celebration, the revelation of Moshiach. May we continue to share in each other’s simchas, and may we go from this simcha to the Ultimate Simcha, the revelation of Moshiach Tzidkeinu, at which time we will once again have the zechus to hear “Torah Chadashah” from the Rebbe. -

MARKING the YARTZEIT of RABBI YEHUDA KALMAN MARLOW 770 Was Packed with Anash and Respect to a True Talmid Chacham Taken Evening

MARKING THE YARTZEIT OF RABBI YEHUDA KALMAN MARLOW 770 was packed with Anash and respect to a true talmid chacham taken evening. Rabbi Avrohom Osdoba tmimim who came to pay their from our midst, but for the most part opened the program by speaking respects on the yartzeit of the Mara by encouraging reports about the about the fatal flaw of the spies. D’asra, Rabbi Yehuda Kalman good deeds and great projects the rav What was their great sin? That they Marlow, a’h. The evening was wanted to see happen. mixed their own opinions into the marked not only by speeches about Rabbi Levi Yitzchok Garelik, a shlichus they had received from the past, not only by a show of close friend of the rav, emceed the Moshe Rabbeinu. They decided the Jewish people would not be able to enter Eretz Yisroel despite what Moshe said. Involving their own limited intellect was their downfall. In addition to all his other qualities, Rabbi Marlow, a’h excelled in his bittul to the Nasi HaDor. His hiskashrus and bittul to the Rebbe was well known. Rabbi Garelik said, “We must learn proper hiskashrus and true bittul to the Rebbe from his conduct. May this hasten our true Redemption and ‘arise and sing those who dwell in the dust,’ and he among them.” Rabbi Y.Y. Marlow, son of the rav, made a siyum on Meseches Sanhedrin. Rabbi Garelik mentioned the Issue Number 328 BEIS MOSHIACH i 37 “TIFERES YEHUDA KALMAN” The book begins with a sicha about the role of the Many people knew Rabbi Marlow: lamdanim, rabbanim and goes on to other pertinent Chassidim, rabbanim, Crown Heights information about the Crown Heights beis residents, women and children, and people din. -

Noahidism Or B'nai Noah—Sons of Noah—Refers To, Arguably, a Family

Noahidism or B’nai Noah—sons of Noah—refers to, arguably, a family of watered–down versions of Orthodox Judaism. A majority of Orthodox Jews, and most members of the broad spectrum of Jewish movements overall, do not proselytize or, borrowing Christian terminology, “evangelize” or “witness.” In the U.S., an even larger number of Jews, as with this writer’s own family of orientation or origin, never affiliated with any Jewish movement. Noahidism may have given some groups of Orthodox Jews a method, arguably an excuse, to bypass the custom of nonconversion. Those Orthodox Jews are, in any event, simply breaking with convention, not with a scriptural ordinance. Although Noahidism is based ,MP3], Tạləmūḏ]תַּלְמּוד ,upon the Talmud (Hebrew “instruction”), not the Bible, the text itself does not explicitly call for a Noahidism per se. Numerous commandments supposedly mandated for the sons of Noah or heathen are considered within the context of a rabbinical conversation. Two only partially overlapping enumerations of seven “precepts” are provided. Furthermore, additional precepts, not incorporated into either list, are mentioned. The frequently referenced “seven laws of the sons of Noah” are, therefore, misleading and, indeed, arithmetically incorrect. By my count, precisely a dozen are specified. Although I, honestly, fail to understand why individuals would self–identify with a faith which labels them as “heathen,” that is their business, not mine. The translations will follow a series of quotations pertinent to this monotheistic and ,MP3], tạləmūḏiy]תַּלְמּודִ י ,talmudic (Hebrew “instructive”) new religious movement (NRM). Indeed, the first passage quoted below was excerpted from the translated source text for Noahidism: Our Rabbis taught: [Any man that curseth his God, shall bear his sin. -

Return of Private Foundation

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491015004014 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2012 Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Internal Revenue Service • . For calendar year 2012 , or tax year beginning 06 - 01-2012 , and ending 05-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number CENTURY 21 ASSOCIATES FOUNDATION INC 22-2412138 O/o RAYMOND GINDI ieiepnone number (see instructions) Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite U 22 CORTLANDT STREET Suite City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here F NEW YORK, NY 10007 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here (- r-Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation H Check type of organization FSection 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation r'Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F of y e a r (from Part 77, col. (c), Other (specify) _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination line 16)x$ 4,783,143 -

Esnoga Bet Emunah Esnoga Bet El 6970 Axis St

Esnoga Bet Emunah Esnoga Bet El 6970 Axis St. SE 102 Broken Arrow Dr. Lacey, WA 98513 Paris TN 38242 United States of America United States of America © 2017 © 2017 http://www.betemunah.org/ http://torahfocus.com/ E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Triennial Cycle (Triennial Torah Cycle) / Septennial Cycle (Septennial Torah Cycle) Three and 1/2 year Lectionary Readings Third Year of the Triennial Reading Cycle Tebet 05, 5778 – Dec 22/23, 2017 Third Year of the Shmita Cycle Candle Lighting and Habdalah Times: Please go to the below webpage and type your city, state/province, and country to find candle lighting and Habdalah times for the place of your dwelling. See: http://www.chabad.org/calendar/candlelighting.htm Roll of Honor: His Eminence Rabbi Dr. Hillel ben David and beloved wife HH Giberet Batsheva bat Sarah His Eminence Rabbi Dr. Eliyahu ben Abraham and beloved wife HH Giberet Dr. Elisheba bat Sarah His Honor Paqid Adon David ben Abraham His Honor Paqid Adon Ezra ben Abraham and beloved wife HH Giberet Karmela bat Sarah, His Honor Paqid Adon Tsuriel ben Abraham and beloved wife HH Giberet Gibora bat Sarah Her Excellency Giberet Sarai bat Sarah & beloved family His Excellency Adon Barth Lindemann & beloved family His Excellency Adon John Batchelor & beloved wife Her Excellency Giberet Leah bat Sarah & beloved mother Her Excellency Giberet Zahavah bat Sarah & beloved family His Excellency Adon Gabriel ben Abraham and beloved wife HE Giberet Elisheba bat Sarah His Excellency Adon Yehoshua ben Abraham and beloved wife HE Giberet Rut bat Sarah His Excellency Adon Michael ben Yosef and beloved wife HE Giberet Sheba bat Sarah Her Excellency Giberet Prof. -

Communications

COMMUNICATIONS DIVINE JUSTICE tov 10. Why cannot Rabbi Granatstein To THE EDITOR OF TRADITION: accept the traditional explanation of Jonah's conduct namely: Jonah In Rabbi Granatstein's recent knew that Nineveh was likely to article "Theodicy and Belief (TRA- repent in contrast with the conduct DITION, Winter 1973), he sug- of Israel who had had ample warn- gests that Jonah's motivation in ings of doom without responding trying to escape his mission to to them. The fate of Israel would Nineveh was that he could not ac- be negatively affected by an action cept "the unjustifiable selectivity of Jonah. Rather than become the involved in Divine "descent"; that willng instrument of his own peo- God's desire to save Nineveh is ple's destruction, Jonah preferred "capricious and violates the univer- self-destruction to destruction of sal justice in which Jonah be- his people. In a conflct between lieves." These are strong words loyalty to his people and loyalty which are not supported by quo- to God Jonah chose the former _ tations -from traditional sources. to his discredit, of course. In this Any student of Exodus 33: 13 is vein, Jonah's actions are explained familar with Moses's quest for un- by Redak, Malbin, Abarbarnel derstanding the ways of Divine based on M ekhilta in Parshat Bo. Providence and is also familar Why must we depart from this in- with the answer in 33: 19, "And I terpretation? shall be gracious to whom I shall Elias Munk show mercy." The selectivity of Downsview, Ontario God's providence has thus been well established ever since the days of the golden calf and it would RABBi GRANA TSTEIN REPLIES: seem unlikely that God had cho- sen a prophet who was not perfect- I cannot agree with Mr. -

“Y Nosotros Somos Tu Pueblo Y El Rebaño De Tu Pastoreo”

AÑO 19 / N° 67 / TISHREI 5779/ PRIMAVERA 2018 “Y nosotros somos Tu pueblo y el rebaño de Tu pastoreo” Shaná Tová Umetuká 2 3 contenido 67 15 destaque 6 EDITORIAL ¿ESTÁS PARA COSER BOTONES? -Rabino Eliezer Shemtov 10 CARTA DEL REBE 33 NADIE ES INCAPAZ DE LOGRAR SU OBJETIVO 22 TORÁ Y CIENCIA ¿CUÁNTOS AÑOS TIENE EL UNIVERSO DE ACUERDO AL JUDAÍSMO? -Tzvi Freeman 46 SALUD REHABILITANDO VIDAS DE LAS ADICCIONES 46 -Miriam Karp 50 MUJER JUDÍA ¿QUÉ HACER CUANDO NOS DECEPCIONAN? -Rosally Saltsman 53 HISTORIAS JASÍDICAS EL BURRO INGENIOSO -Yaakov Lieder NUESTRA TAPA Publicación de Beit Jabad Uruguay. Pereyra de La Luz 1130 Los comienzos son siempre lindos; sueños, esperanza y fuerzas renovadas. Rosh 11300, Montevideo-Uruguay. Tel.: (+598) 26286770 Hashaná no es meramente el aniversario E-mail: [email protected]. de la creación del universo; según los Director: Rabino Eliezer Shemtov místicos judíos, en Rosh Hashaná Di-s Editor: Daniel Laizerovitz vuelve a crear al hombre y Su universo, Traducciones: Marcos Jerouchalmi dotándoles de nuevas fuerzas. Que sea un Foto de tapa: Johanna Avayú año de bendición, éxitos y satisfacciones para todos. Se imprime en MERALIR S.A. ¡Mashíaj ya! D.L.: Nº 369.704, Guayabo 1672 ¡Shaná Tová Umetuká! Agradecemos a www.chabad.org por habernos autorizado a reproducir varios de los artículos publicados en este número. Si sabe de alguien que quiera FE DE ERRATAS: conocer la revista Kesher y no la recibe, o si usted cambió de dirección, le Se hace constar que en la última rogamos que nos lo haga saber de inmediato al edición de Kesher (No 66), pág. -

Title Ix Policy

CENTRAL YESHIVA TOMCHEI TMIMIM LUBAVITZ TITLE IX POLICY Central Yeshiva Tomchei Tmimim Lubavitz (hereafter called “Yeshiva”) is committed to maintaining an environment where all students are granted equal access to education based on the federal Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, and subsequent revisions. The latest regulatory update was published as a Final Rule in the Federal Register on May 19, 2020 is effective on August 14, 2020. The Yeshiva will adhere to a strict policy with regard to sexual violence, which includes any form of sexual assault, domestic violence, dating violence, stalking or any other form of sexual misconduct. The Yeshiva has developed a policy to promptly and effectively respond to any incident of sexual violence or sexual misconduct in accordance with the Title IX Final Rule. The Yeshiva takes as a serious responsibility its obligation to address all incidents of sexual misconduct, violence and offensive or inappropriate demeanor that take place in the school’s educational program or activity. Behaviors under the following three categories will be addressed in this policy: • Quid pro quo harassment by a school’s employee • Unwelcome conduct that a reasonable person would find so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it denies a person equal educational access • Instance of sexual assault (as defined in the Clery Act), including dating violence, domestic violence, or stalking as defined in the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) While meeting its legal requirements the Yeshiva strives to go beyond compliance and is dedicated to maintain a supportive environment for victims of abuse and discrimination. As an appendix, the Yeshiva is providing a list of resources and support that are culturally sensitive to Orthodox Jewish victims. -

Raging Regret As Super-Spreader Event Hits Community

Lucas Tandokwazi Sithole Alexander Rose-Innes, Oak Trees, oil on canvas The Coalbrook Widow, carved SOLD R70,000 wood painted with liquid steel SOLD R36,000 19th century oak 2-door cabinet SOLD R22,000 Art, antiques, objets d’art, furniture, and jewellery wanted Edinburgh silver teakettle on stand complete with for forthcoming auctions burner SOLD R20,000 View upcoming auction highlights at www.rkauctioneers.co.za 011 789 7422 • 011 326 3515 • 083 675 8468 • 12 Allan Road, Bordeaux, Johannesburg south african n Volume 24 – Number 45 n 11 December 2020 n 25 Kislev 5781 The source of quality content, news and insights t www.sajr.co.za Raging regret as super-spreader event hits community TALI FEINBERG A matriculant who went on Rage and have been really careful since I got back.” “Yes we can blame parents and some virus on Rage says, “Rage was the one thing contracted COVID-19, says, “I knew the risks, A mother whose daughter attended are regretting that they didn’t exert their that got my child through matric. He had the matric pupil lies in high care at a but I had so much taken away this year. I had Rage and contracted the virus blames authority, but the fact is that we’ve kept time of his life, but at what cost? We have Johannesburg Netcare hospital. nothing to look forward to. Going on Rage felt the organisers. Speaking on condition of 18-year-olds locked up for a year. They were been so careful, but we just couldn’t say no to Her peers are being admitted like it was only fair. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Days in Chabad

M arC heshvan of the First World War, and as a consequence, the Hirkish authorities decided to expel all Russian nationals living in Eretz Yisrael. Thus, teacher and students alike were obli gated to abandon Chevron and malte the arduous journey back to Russia. Tohioi Chabad b'Eretz Hakodesh Passing of Rabbi Avraham Schneersohn, 2 Mar- FATHER-IN-LAW OF THE ReBBE, R, YOSEF YiTZCHAK Cheshvan 5 6 9 8 /1 9 3 7 Rabbi Avraham Schneersohn was bom in Lubavitch, in S ivan 5620 (1860). His father was Rabbi Yisrael Noach, son of the Tzemach Tkedek ; his mother, Rebbetzin Freida, daughter of Rebbetzin Baila, who was the daughter of the Mitteler Rebbe. In the year 5635 (1875), he married Rebbetzin Yocheved, daughter of Rabbi Yehoshua Fallilc Sheinberg, one of the leading chasidim in the city of Kishinev. After his marriage, he made his home in !Kishinev and dedicat ed himself to the study of Torah and the service of G-d. Rabbi Avraham was well-known for his righteousness, his piety and his exceptional humility. When his father passed away, his chasidim were most anxious for Rabbi Avraham to take his place, but he declined to do so and remained in Kishinev. In order to support himself he went into business, even then devoting the rest of his life to the study of Torah and the service of G-d. He was interred in Kishinev. Hakriah v’Hakedusha Passing of Rabbi Yehuda Leib, the “M aharil” 3 Mar- OF KoPUST, son of THE TZEMACH TZEDEK Cheshvan 5 6 2 7 /1 8 6 6 Rabbi Yehuda Leib, known as the “Maharil,” was bom in 5568 (1808). -

Divine Image,Prospectives on Noahide Laws

Divine Image Divine Image View All Divine Image Book Insights into the Noahide Laws Through the light of Torah and Chabad philosophy Adapted by Rabbi Yakov Dovid Cohen Copyright © 2006 by Rabbi Yakov Dovid Cohen All Rights Reserved ISBN 1-4243-1000-8 978-1-4243-1000-5 Published by The Institute of Noahide Code www.Noahide.org Printed in the United States of America In English En Español En français En français En français 한국어 中文 اﻟﺬات اﻹﻟﻬﻴﺔ INTRODUCTION Every person is created with a Divine image. It is the task of every one of us to elevate all human activity to a Divine purpose. In short, this means being able to connect every human activity with G-d – and this is precisely the purpose of the Torah and its commandments, called mitzvoth in Hebrew. Every human being has the unique ability to connect his entire being with the Creator. Upon achieving this task, he creates a dwelling place for G-d in this world, thereby fulfilling the purpose of creation. As is explained in this book, the worlds of the spiritual and the physical are not in conflict. Their ultimate purpose is that they be fused together with the physical being permeated by the spiritual. The core element of every mitzvah – commandment performance is to take the physical creation and utilize it for a Divine purpose. Thereby a wonderful harmony achieving both in the individual and in the world at large. This is a theme that encompasses all times and places; wherever and whenever a person operates, he is able to utilize the task at hand for its correct and Divine purpose, thus transforming one’s daily life activities into a dwelling place for G-d.