Robertson 19 (1954)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\Documents and Settings\Alan Smithee\My Documents\MOTM

I`mt`qx1/00Lhmdq`knesgdLnmsg9Rbnkdbhsd This month’s mineral, scolecite, is an uncommon zeolite from India. Our write-up explains its origin as a secondary mineral in volcanic host rocks, the difficulty of collecting this fragile mineral, the unusual properties of the zeolite-group minerals, and why mineralogists recently revised the system of zeolite classification and nomenclature. OVERVIEW PHYSICAL PROPERTIES Chemistry: Ca(Al2Si3O10)A3H2O Hydrous Calcium Aluminum Silicate (Hydrous Calcium Aluminosilicate), usually containing some potassium and sodium. Class: Silicates Subclass: Tectosilicates Group: Zeolites Crystal System: Monoclinic Crystal Habits: Usually as radiating sprays or clusters of thin, acicular crystals or Hairlike fibers; crystals are often flattened with tetragonal cross sections, lengthwise striations, and slanted terminations; also massive and fibrous. Twinning common. Color: Usually colorless, white, gray; rarely brown, pink, or yellow. Luster: Vitreous to silky Transparency: Transparent to translucent Streak: White Cleavage: Perfect in one direction Fracture: Uneven, brittle Hardness: 5.0-5.5 Specific Gravity: 2.16-2.40 (average 2.25) Figure 1. Scolecite. Luminescence: Often fluoresces yellow or brown in ultraviolet light. Refractive Index: 1.507-1.521 Distinctive Features and Tests: Best field-identification marks are acicular crystal habit; vitreous-to-silky luster; very low density; and association with other zeolite-group minerals, especially the closely- related minerals natrolite [Na2(Al2Si3O10)A2H2O] and mesolite [Na2Ca2(Al6Si9O30)A8H2O]. Laboratory tests are often needed to distinguish scolecite from other zeolite minerals. Dana Classification Number: 77.1.5.5 NAME The name “scolecite,” pronounced SKO-leh-site, is derived from the German Skolezit, which comes from the Greek sklx, meaning “worm,” an allusion to the tendency of its acicular crystals to curl when heated and dehydrated. -

Mineral Processing

Mineral Processing Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy 1st English edition JAN DRZYMALA, C. Eng., Ph.D., D.Sc. Member of the Polish Mineral Processing Society Wroclaw University of Technology 2007 Translation: J. Drzymala, A. Swatek Reviewer: A. Luszczkiewicz Published as supplied by the author ©Copyright by Jan Drzymala, Wroclaw 2007 Computer typesetting: Danuta Szyszka Cover design: Danuta Szyszka Cover photo: Sebastian Bożek Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej Wybrzeze Wyspianskiego 27 50-370 Wroclaw Any part of this publication can be used in any form by any means provided that the usage is acknowledged by the citation: Drzymala, J., Mineral Processing, Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy, Oficyna Wydawnicza PWr., 2007, www.ig.pwr.wroc.pl/minproc ISBN 978-83-7493-362-9 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 Part I Introduction to mineral processing .....................................................................13 1. From the Big Bang to mineral processing................................................................14 1.1. The formation of matter ...................................................................................14 1.2. Elementary particles.........................................................................................16 1.3. Molecules .........................................................................................................18 1.4. Solids................................................................................................................19 -

A Mineralogy of Anthropocene E

1 A Minerology for the Anthropocene Pierre FLUCK Institut Universitaire de France / Docteur-ès-Sciences / geologist and archeologist / Emeritus Professor at Université de Haute-Alsace This essay is a follow-up on « La signature stratigraphique de l’Anthropocène », which is also available on HAL- Archives ouvertes. Table of contents 1. Introduction: neoformation minerals in ancient mining galleries 2. Minerals from burning coal mines 3. Minerals from the mineral processing industry 4 ...and metallurgy 5. Neoformations in slags 6. Speciation of heavy metals in soils 7. Metal objects in their archaeological environment, or affected by fire 8. Neoformations in or on the surface of building stones 9. A mineralogy of materials. The “miracle of the potter”. The minerals in cement 10. A mineralogy of the biosphere? Conclusions Warning. This paper is written to be read by both specialists and a wider audience. However, it contains many mineral names. While these may resonate in the minds of mineralogists or collectors, they may not be as meaningful to less discerning readers. Such readers should not be scared, for they may find excellent encyclopaedic records on the web, including chemical composition, crystallographic properties and description of each of these species. This is why we have decided not to include further information in this paper. Acknowledgements. I would like to thank the mineralogists with whom I have had the opportunity to maintain fruitful exchanges for a long time: my pupil Hubert Bari, Éric Asselborn, Cédric Lheur, François Farges. And I would like to honour the memories of René Weil (1901-1983), my master in descriptive mineralogy, and of Jacques Geffroy (1918-1993), pupil of Alfred Lacroix, my master in metallogeny. -

: Crystal Structure and Revision of Chemical Formula](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1463/cafetite-ca-ti2o5-h2o-crystal-structure-and-revision-of-chemical-formula-371463.webp)

Cafetite, Ca[Ti2o5](H2O): Crystal Structure and Revision of Chemical Formula

American Mineralogist, Volume 88, pages 424–429, 2003 Cafetite, Ca[Ti2O5](H2O): Crystal structure and revision of chemical formula SERGEY V. K RIVOVICHEV,1,* VICTOR N. YAKOVENCHUK,2 PETER C. BURNS,3 YAKOV A. PAKHOMOVSKY,2 AND YURY P. MENSHIKOV2 1Department of Crystallography, St. Petersburg State University, University Embankment 7/9, St. Petersburg 199034, Russia 2Geological Institute, Kola Science Centre, Russian Academy of Sciences, Fersmana 14, 184200-RU Apatity, Russia 3Department of Civil Engineering and Geological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556-0767, U.S.A. ABSTRACT The crystal structure of cafetite, ideally Ca[Ti2O5](H2O), (monoclinic, P21/n, a = 4.9436(15), b = 12.109(4), c = 15.911(5) Å, b = 98.937(5)∞, V = 940.9(5) Å3, Z = 8) has been solved by direct methods and refined to R1 = 0.057 using X-ray diffraction data collected from a crystal pseudo-merohedrally twinned on (001). There are four symmetrically independent Ti cations; each is octahedrally coordi- nated by six O atoms. The coordination polyhedra around the Ti cations are strongly distorted with individual Ti-O bond lengths ranging from 1.743 to 2.223 Å (the average <Ti-O> bond length is 1.98 Å). Two symmetrically independent Ca cations are coordinated by six and eight anions for Ca1 and Ca2, respectively. The structure is based on [Ti2O5] sheets of TiO6 octahedra parallel to (001). The Ca atoms and H2O groups are located between the sheets and link them into a three-dimensional struc- ture. The structural formula of cafetite confirmed by electron microprobe analysis is Ca[Ti2O5](H2O), . -

The Minerals and Rocks of the Earth 5A: the Minerals- Special Mineralogy

Lesson 5 cont’d: The Minerals and Rocks of the Earth 5a: The minerals- special mineralogy A. M. C. Şengör In the previous lectures concerning the materials of the earth, we studied the most important silicates. We did so, because they make up more than 80% of our planet. We said, if we know them, we know much about our planet. However, on the surface or near-surface areas of the earth 75% is covered by sedimentary rocks, almost 1/3 of which are not silicates. These are the carbonate rocks such as limestones, dolomites (Americans call them dolostones, which is inappropriate, because dolomite is the name of a person {Dolomieu}, after which the mineral dolomite, the rock dolomite and the Dolomite Mountains in Italy have been named; it is like calling the Dolomite Mountains Dolo Mountains!). Another important category of rocks, including parts of the carbonates, are the evaporites including halides and sulfates. So we need to look at the minerals forming these rocks too. Some of the iron oxides are important, because they are magnetic and impart magnetic properties on rocks. Some hydroxides are important weathering products. This final part of Lesson 5 will be devoted to a description of the most important of the carbonate, sulfate, halide and the iron oxide minerals, although they play a very little rôle in the total earth volume. Despite that, they play a critical rôle on the surface of the earth and some of them are also major climate controllers. The carbonate minerals are those containing the carbonate ion -2 CO3 The are divided into the following classes: 1. -

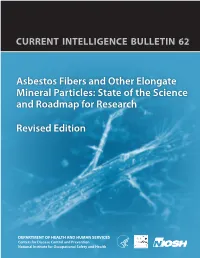

Asbestos Fibers and Other Elongate Mineral Particles: State of the Science and Roadmap for Research

CURRENT INTELLIGENCE BULLETIN 62 Asbestos Fibers and Other Elongate Mineral Particles: State of the Science and Roadmap for Research Revised Edition DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Cover Photograph: Transitional particle from upstate New York identified by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) as anthophyllite asbestos altering to talc. Photograph courtesy of USGS. CURRENT INTELLIGENCE BULLETIN 62 Asbestos Fibers and Other Elongate Mineral Particles: State of the Science and Roadmap for Research DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health This document is in the public domain and may be freely copied or reprinted. Disclaimer Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the Na- tional Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations to Web sites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the spon- soring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these Web sites. Ordering Information To receive NIOSH documents or other information about occupational safety and health topics, contact NIOSH at Telephone: 1–800–CDC–INFO (1–800–232–4636) TTY: 1–888–232–6348 E-mail: [email protected] or visit the NIOSH Web site at www.cdc.gov/niosh. For a monthly update on news at NIOSH, subscribe to NIOSH eNews by visiting www.cdc.gov/niosh/eNews. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2011–159 (Revised for clarification; no changes in substance or new science presented) April 2011 Safer • Healthier • PeopleTM ii Foreword Asbestos has been a highly visible issue in public health for over three decades. -

The Partnership of Smithson Tennant and William Hyde Wollaston

“A History of Platinum and its Allied Metals”, by Donald McDonald and Leslie B. Hunt 9 The Partnership of Smithson Tennant and William Hyde Wollaston “A quantity of platina was purchased by me a few years since with the design of rendering it malleable for the different purposes to which it is adapted. That object has now been attained. ” WILLIAM HYDE W O L L A S T O N Up to the end of the eighteenth century the attempts to produce malleable platinum had advanced mainly in the hands of practical men aiming at its pre paration and fabrication rather than at the solution of scientific problems. These were now to be attacked with a marked degree of success by two remarkable but very different men who first became friends during their student days at Cam bridge and who formed a working partnership in 1800 designed not only for scientific purposes but also for financial reasons. They were of the same genera tion and much the same background as the professional scientists of London whose work was described in Chapter 8, and to whom they were well known, but with the exception of Humphry Davy they were of greater stature and made a greater advance in the development of platinum metallurgy than their predecessors. Their combined achievements over a relatively short span of years included the successful production for the first time of malleable platinum on a truly com mercial scale as well as the discovery of no less than four new elements contained in native platinum, a factor that was of material help in the purification and treatment of platinum itself. -

Optical Properties of Common Rock-Forming Minerals

AppendixA __________ Optical Properties of Common Rock-Forming Minerals 325 Optical Properties of Common Rock-Forming Minerals J. B. Lyons, S. A. Morse, and R. E. Stoiber Distinguishing Characteristics Chemical XI. System and Indices Birefringence "Characteristically parallel, but Mineral Composition Best Cleavage Sign,2V and Relief and Color see Fig. 13-3. A. High Positive Relief Zircon ZrSiO. Tet. (+) 111=1.940 High biref. Small euhedral grains show (.055) parallel" extinction; may cause pleochroic haloes if enclosed in other minerals Sphene CaTiSiOs Mon. (110) (+) 30-50 13=1.895 High biref. Wedge-shaped grains; may (Titanite) to 1.935 (0.108-.135) show (110) cleavage or (100) Often or (221) parting; ZI\c=51 0; brownish in very high relief; r>v extreme. color CtJI\) 0) Gamet AsB2(SiO.la where Iso. High Grandite often Very pale pink commonest A = R2+ and B = RS + 1.7-1.9 weakly color; inclusions common. birefracting. Indices vary widely with composition. Crystals often euhedraL Uvarovite green, very rare. Staurolite H2FeAI.Si2O'2 Orth. (010) (+) 2V = 87 13=1.750 Low biref. Pleochroic colorless to golden (approximately) (.012) yellow; one good cleavage; twins cruciform or oblique; metamorphic. Olivine Series Mg2SiO. Orth. (+) 2V=85 13=1.651 High biref. Colorless (Fo) to yellow or pale to to (.035) brown (Fa); high relief. Fe2SiO. Orth. (-) 2V=47 13=1.865 High biref. Shagreen (mottled) surface; (.051) often cracked and altered to %II - serpentine. Poor (010) and (100) cleavages. Extinction par- ~ ~ alleL" l~4~ Tourmaline Na(Mg,Fe,Mn,Li,Alk Hex. (-) 111=1.636 Mod. biref. -

New Mineral Names

NEW MINERAL NAMES Ilarkerite C. E. T[,rnv, The zoned contact-skarns of the Broadford area, Skye: a study of boron- fluorine metasomatism in dolomites: Mineralog. Mag ,29, 621-666 (1951). Crrurcar.: Analysis by H. C. G. Vincent gave SiO: 14.17, BzOa7.77, AlzOt 2.84, FezOr 0.85, FeO 0.46, MnO 0.02, MgO 11.15, CaO 46.23, COz 14.94,Cl 1'36, H2O+ 0.81' HrO- 0.11; sum 100.71,less O:Cl 0.31, lOO.4O7o.The formula is discussed;a rough fit with the unit cell is given by the lollowing: 20CaCOs'Cax(Mg, A1, etc.)zo(B, Si)zr(O, OH, Cl)s6' The Mg group has Mg 15'65, At 3.16, Fe'r' 0.60, Fe" 0.36, the (B, Si) group has Si 13.35,B 12.63- The mineral dissolves with efiervescence in acetic or hydrochloric acids; gives a good flame test for boron. Heated to 850o, it decomposes to a turbid brown product. Cnvse.lr,r-ocn-lPnrc AND X-R,c.v Dere: X-ray study by N. F. M. Henry give the Laue .gtotp m3m and the tests for pyro- and piezo-electricity were negative. The crystal class is probably m3m ((]ttbic holohedral). The cell has a:29.53*.01 A., with a pseudo-cell at 14.76 A. This pseudo-cell contains the formula given above. X-ray powder data are given: the strongest lines are (l) 2.61, (2) 1.84, (3) 2.13, (4) 1.51 A. Psvsrclr- nql Oprrc.lr,: Harkerite occurs typically as simple octahedra that are color- less with vitreous luster, but alter to white masses of calcite. -

Phyllosilicates in the Sediment-Forming Processes: Weathering, Erosion, Transportation, and Deposition

Acta Geodyn. Geomater., Vol. 6, No. 1 (153), 13–43, 2009 PHYLLOSILICATES IN THE SEDIMENT-FORMING PROCESSES: WEATHERING, EROSION, TRANSPORTATION, AND DEPOSITION Jiří KONTA Faculty of Sciences, Charles University, Albertov 6, 128 43 Prague 2 Home address: Korunní 127, 130 00 Prague 3, Czech Republic *Corresponding author‘s e-mail: [email protected] (Received October 2008, accepted January 2009) ABSTRACT Phyllosilicates are classified into the following groups: 1 - Neutral 1:1 structures: the kaolinite and serpentine group. 2 - Neutral 2:1 structures: the pyrophyllite and talc group. 3 - High-charge 2:1 structures, non-expansible in polar liquids: illite and the dioctahedral and trioctahedral micas, also brittle micas. 4 - Low- to medium-charge 2:1 structures, expansible phyllosilicates in polar liquids: smectites and vermiculites. 5 - Neutral 2:1:1 structures: chlorites. 6 - Neutral to weak-charge ribbon structures, so-called pseudophyllosilicates or hormites: palygorskite and sepiolite (fibrous crystalline clay minerals). 7 - Amorphous clay minerals. Order-disorder states, polymorphism, polytypism, and interstratifications of phyllosilicates are influenced by several factors: 1) a chemical micromilieu acting during the crystallization in any environment, including the space of clay pseudomorphs after original rock-forming silicates or volcanic glasses; 2) the accepted thermal energy; 3) the permeability. The composition and properties of parent rocks and minerals in the weathering crusts, the elevation, and topography of source areas and climatic conditions control the intensity of weathering, erosion, and the resulting assemblage of phyllosilicates to be transported after erosion. The enormously high accumulation of phyllosilicates in the sedimentary lithosphere is primarily conditioned by their high up to extremely high chemical stability in water-rich environments (expressed by index of corrosion, IKO). -

Standard X-Ray Diffraction Powder Patterns NATIONAL BUREAU of STANDARDS

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS & TECHNOLOGY Research Information Center Gaithersburg, MD 20899 NATL INST OF STANDARDS & TECH R.I.C. A1 11 00988606 /NBS monograph QC100 .U556 V25-12;1975 C.1 NBS-PUB-C 19 NBS MONOGRAPH 25 " SECTION 12 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE / National Bureau of Standards Standard X-ray Diffraction Powder Patterns NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS 1 The National Bureau of Standards was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau consists of the Institute for Basic Standards, the Institute for Materials Research, the Institute for Applied Technology, the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology, and the Office for Information Programs. THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS provides the central basis within the United States of a complete and consistent system of physical measurement; coordinates that system with measurement systems of other nations; and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. The Institute consists of a Center for Radiation Research, an Office of Meas- urement Services and the following divisions: Applied Mathematics — Electricity — Mechanics — Heat — Optical Physics — Nuclear Sciences 2 — Applied Radiation 2 — Quantum Electronics 3 — Electromagnetics 3 — Time 3 3 3 and Frequency — Laboratory Astrophysics — Cryogenics . -

Italian Type Minerals / Marco E

THE AUTHORS This book describes one by one all the 264 mi- neral species first discovered in Italy, from 1546 Marco E. Ciriotti was born in Calosso (Asti) in 1945. up to the end of 2008. Moreover, 28 minerals He is an amateur mineralogist-crystallographer, a discovered elsewhere and named after Italian “grouper”, and a systematic collector. He gradua- individuals and institutions are included in a pa- ted in Natural Sciences but pursued his career in the rallel section. Both chapters are alphabetically industrial business until 2000 when, being General TALIAN YPE INERALS I T M arranged. The two catalogues are preceded by Manager, he retired. Then time had come to finally devote himself to his a short presentation which includes some bits of main interest and passion: mineral collecting and information about how the volume is organized related studies. He was the promoter and is now the and subdivided, besides providing some other President of the AMI (Italian Micromineralogical As- more general news. For each mineral all basic sociation), Associate Editor of Micro (the AMI maga- data (chemical formula, space group symmetry, zine), and fellow of many organizations and mine- type locality, general appearance of the species, ralogical associations. He is the author of papers on main geologic occurrences, curiosities, referen- topological, structural and general mineralogy, and of a mineral classification. He was awarded the “Mi- ces, etc.) are included in a full page, together cromounters’ Hall of Fame” 2008 prize. Etymology, with one or more high quality colour photogra- geoanthropology, music, and modern ballet are his phs from both private and museum collections, other keen interests.