Chapter 2: Cultural Heritage Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Discovery Guide

saskatchewan discovery guide OFFICIAL VACATION AND ACCOMMODATION PLANNER CONTENTS 1 Contents Welcome.........................................................................................................................2 Need More Information? ...........................................................................................4 Saskatchewan Tourism Zones..................................................................................5 How to Use the Guide................................................................................................6 Saskatchewan at a Glance ........................................................................................9 Discover History • Culture • Urban Playgrounds • Nature .............................12 Outdoor Adventure Operators...............................................................................22 Regina..................................................................................................................... 40 Southern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 76 Saskatoon .............................................................................................................. 158 Central Saskatchewan ....................................................................................... 194 Northern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 276 Events Guide.............................................................................................................333 -

Résultats Par Circonscription Des Élections De 1999

Résultats par circonscription des élections de 1999 1. Arm River Lib : 31 % NPD : 25 % Sask : 44 % 2. Athabasca Lib : 13 % NPD : 84 % Sask: 3 % 3. Battleford-Cut Knife Lib : 18 % NPD: 36 % Sask: 46 % 4. Cannington Lib : 10 % NPD : 15 % Sask : 75 % 5. Canora-Pelly Lib : 12 % NPD : 28 % Sask: 58 % 6. Carrot River Valley Lib : 9 % NPD: 40 % Sask: 51 % 7. Cumberland Lib: 18 % NPD: 69 % Sask: 3 % 8. Cypress Hills Lib: 16 % NPD: 21 % Sask: 63 % 9. Estevan Lib: 32 % NPD: 19 % NGA: 2 % Sask: 47 % 10. Humboldt Lib: 17 % NPD: 35 % NGA: 3 % Sask: 45 % 11. Indian Head-Milestone Lib: 21 % NPD: 29 % NGA: 2 % Sask: 45 % 12. Kelvington-Wadena Lib: 6 % NPD: 28 % Sask: 66 % 13. Kindersley Lib: 16 % NPD: 20 % Sask: 63 % 14. Last Moutain-Touchwood Lib: 17 % NPD: 36 % Sask: 47 % 15. Lloydminster Lib: 8 % NPD: 39 % Sask: 53 % 16. Meadow Lake Lib: 12 % NPD: 47 % Sask: 41 % 17. Melfort-Tisdale Lib: 17 % NPD: 32 % Sask: 52 % 18. Melville Lib: 45 % NPD: 27 % Sask: 28 % 19. Moose Jaw nord Lib: 9 % NPD: 50 % Sask: 41 % 20. Moose Jaw Wakamow Lib: 11 % NPD: 54 % PC: 2 % Sask: 33 % 21. Moosomin Lib: 20 % NPD: 21 % Sask: 60 % 22. North Battleford Lib: 48 % NPD: 37 % Sask: 14 % 23. Prince Albert Carlton Lib: 16 % NPD: 54 % Sask: 30 % 24. Prince Albert Northcote Lib: 32 % NPD: 50 % PC: 3 % Sask: 15 % 25. Redberry Lake Lib: 14 % NPD: 32 % NGA: 2 % Sask: 51 % 26. Regina Centre Lib : 22 % NPD : 52 % NGA: 8 % PC: 3 % Sask : 15 % 27. Regina Coronation Park Lib: 22 % NPD: 52 % PC: 2 % Sask: 24 % 28. -

The 31 S T Annual

THE 31ST ANNUAL NOVEMBER 10, 2020 NOVEMBER 10, 2020 MASTER OF CEREMONIES Mary Taylor-Ash CEO Tourism Saskatchewan PRESENTER Norm Beug Chair Tourism Saskatchewan Board of Directors 2 NOVEMBER 10, 2020 SASKATCHEWAN TOURISM AWARDS OF EXCELLENCE More than 30 years ago, Saskatchewan’s tourism sector began paying special tribute to leadership and achievement in the industry – to businesses and individuals who made exceptional contributions to tourism and demonstrated that success and fulfilment come with being true to your dreams, proud of your home and eager to treat guests to remarkable Saskatchewan experiences. The Saskatchewan Tourism Awards of Excellence Gala has become a yearly showcase of achievement, bringing together representatives from every corner of the province and from a diverse range of businesses and attractions to celebrate the accomplishments of their colleagues in the industry. Originally scheduled to take place on April 2 in Regina, the 31st annual event was cancelled, along with the HOST Saskatchewan Conference, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. With the cancellation of both industry gatherings, the announcement of the 12 Saskatchewan Tourism Awards of Excellence recipients and three Tourism Builders was postponed. Through the use of technology and adoption of a new virtual format, members of Saskatchewan’s tourism industry are now able to gather from afar to honour those outstanding businesses and people who have gone above and beyond to deliver superior service and experiences. Join the celebration as the Saskatchewan Tourism Awards of Excellence shine a spotlight on the commitment and hard work of veteran operators, as well as the innovative spirit of young entrepreneurs, and broaden understanding of efforts that yield success and, ultimately, position Saskatchewan as a more inviting and competitive destination. -

Canada Needs You Volume One

Canada Needs You Volume One A Study Guide Based on the Works of Mike Ford Written By Oise/Ut Intern Mandy Lau Content Canada Needs You The CD and the Guide …2 Mike Ford: A Biography…2 Connections to the Ontario Ministry of Education Curriculum…3 Related Works…4 General Lesson Ideas and Resources…5 Theme One: Canada’s Fur Trade Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 2: Thanadelthur…6 Track 3: Les Voyageurs…7 Key Terms, People and Places…10 Specific Ministry Expectations…12 Activities…12 Resources…13 Theme Two: The 1837 Rebellion Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 5: La Patriote…14 Track 6: Turn Them Ooot…15 Key Terms, People and Places…18 Specific Ministry Expectations…21 Activities…21 Resources…22 Theme Three: Canadian Confederation Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 7: Sir John A (You’re OK)…23 Track 8: D’Arcy McGee…25 Key Terms, People and Places…28 Specific Ministry Expectations…30 Activities…30 Resources…31 Theme Four: Building the Wild, Wild West Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 9: Louis & Gabriel…32 Track 10: Canada Needs You…35 Track 11: Woman Works Twice As Hard…36 Key Terms, People and Places…39 Specific Ministry Expectations…42 Activities…42 Resources…43 1 Canada Needs You The CD and The Guide This study guide was written to accompany the CD “Canada Needs You – Volume 1” by Mike Ford. The guide is written for both teachers and students alike, containing excerpts of information and activity ideas aimed at the grade 7 and 8 level of Canadian history. The CD is divided into four themes, and within each, lyrics and information pertaining to the topic are included. -

Historical Walking and Driving Tours: Victoria Trail, Kalyna Country

Historical Walking and Driving Tours: Victoria and the Victoria Trail This booklet contains a walking tour of the Vic- toria Settlement Historic Site and part of the Vic- toria Trail, and a driving tour of the Victoria Trail west from the Historic Site to Highway 38. The Historic Site is about 1 hour and 40 minutes from Edmonton, either by Highway 28 to Smoky Lake, or along the southern route via Highways 21, 15, 45 and Secondary Highway 855. A map of the tour route showing the location of the sites appears in the center of the booklet. Signs mark the location of the numbered sites described in this tour. Wherever possible, historic names have been used for buildings and sites, names that often do not correspond to their current owners or occupants. Please respect the privacy of property owners along the tour. Inclusion in this publication does not imply that a site is open to the public. Unless otherwise indicated, please view the posted sites from the road. 1 Introduction The first Europeans to venture into the area now known as Alberta were fur traders. Ever more aggressive competition from the North West Com- pany and from assorted free-traders not associated Long before fur traders, missionaries, or settlers with any company drove the Hudson’s Bay Company came to the north bend of the North Saskatchewan to establish posts further and further from its bases River, Aboriginal people were using the area as a on Hudson’s Bay. By the late 1700s, forts were to be seasonal camping ground and staging point for the found across northern Alberta as far as the Rocky annual buffalo hunt. -

The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial

182-199 120820 11/1/04 2:57 PM Page 182 Chapter 13 The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial It is the summer of 1885. The small courtroom The case against Riel is being heard by in Regina is jammed with reporters and curi- Judge Hugh Richardson and a jury of six ous spectators. Louis Riel is on trial. He is English-speaking men. The tiny courtroom is charged with treason for leading an armed sweltering in the heat of a prairie summer. For rebellion against the Queen and her Canadian days, Riel’s lawyers argue that he is insane government. If he is found guilty, the punish- and cannot tell right from wrong. Then it is ment could be death by hanging. Riel’s turn to speak. The photograph shows What has happened over the past 15 years Riel in the witness box telling his story. What to bring Louis Riel to this moment? This is the will he say in his own defence? Will the jury same Louis Riel who led the Red River decide he is innocent or guilty? All Canada is Resistance in 1869-70. This is the Riel who waiting to hear what the outcome of the trial was called the “Father of Manitoba.” He is will be! back in Canada. Reflecting/Predicting 1. Why do you think Louis Riel is back in Canada after fleeing to the United States following the Red River Resistance in 1870? 2. What do you think could have happened to bring Louis Riel to this trial? 3. -

Women of Batoche Batoche's Métis Women Played Many Key Roles

Women of Batoche Batoche’s Métis women played many key roles during the 1885 Resistance. They nursed the wounded, nurtured children and Elders, melted lead to form bullets, provided supplies to the men in the trenches and a few even influenced Métis strategy. While the fighting was raging in Batoche, most of the Métis women, children, and Elders hid themselves in a secluded flat surrounded by bluffs, on the east side of the South Saskatchewan River. Some Cree from the One Arrow and Beardy’s Reserves joined them. The families stayed in tents or dugouts covered with robes, blankets or branches. Mary Fiddler said that her grandmother hid herself and her grandchildren, along the riverbank, under several coats during the day, while at night they used them as blankets. While in hiding, the women shared what little food that they possessed and cared for the children and Elders. In the village, Madeleine (Wilkie) Dumont, Gabriel’s wife, and the elderly Madame Marie (Hallet) Letendre cooked and tended the sick and wounded. Marguerite (née Dumas) Caron influenced Métis strategy during the 1885 Resistance. During the Battle of Fish Creek (April 24, 1885) she told Louis Riel to reinforce the beleaguered Métis forces. She could see that the Métis, including her husband and two sons, were under heavy enemy fire. Riel told her that she should pray for them. At that point, she told Riel that unless he sent reinforcements, she would go herself. Riel listened and sent reinforcements, which prevented the Métis from being defeated. Another strong woman, Marie-Anne (née Caron) Parenteau, told Father Fourmond, in St. -

An Indian Chief, an English Tourist, a Doctor, a Reverend, and a Member of Ppparliament: the Journeys of Pasqua’S’S’S Pictographs and the Meaning of Treaty Four

The Journeys of Pasqua’s Pictographs 109 AN INDIAN CHIEF, AN ENGLISH TOURIST, A DOCTOR, A REVEREND, AND A MEMBER OF PPPARLIAMENT: THE JOURNEYS OF PASQUA’S’S’S PICTOGRAPHS AND THE MEANING OF TREATY FOUR Bob Beal 7204 76 Street Edmonton, Alberta Canada, T6C 2J5 [email protected] Abstract / Résumé Indian treaties of western Canada are contentious among historians, First Nations, governments, and courts. The contemporary written docu- mentation about them has come from one side of the treaty process. Historians add information from such disciplines as First Nations Tradi- tional Knowledge and Oral History to draw as complete a picture as possible. Now, we have an additional source of written contemporary information, Chief Pasqua’s recently rediscovered pictographs showing the nature of Treaty Four and its initial implementation. Pasqua’s ac- count, as contextualized here, adds significantly to our knowledge of the western numbered treaty process. The pictographs give voice to Chief Pasqua’s knowledge. Les traités conclus avec les Indiens de l’Ouest canadien demeurent liti- gieux pour les historiens, les Premières nations, les gouvernements et les tribunaux. Les documents contemporains qui discutent des traités ne proviennent que d’une seule vision du processus des traités. Les historiens ajoutent des renseignements provenant de disciplines telles que les connaissances traditionnelles et l’histoire orale des Autochto- nes. Ils bénéficient désormais d’une nouvelle source écrite contempo- raine, les pictogrammes récemment redécouverts du chef Pasqua, qui illustrent la nature du Traité n° 4 et les débuts de son application. Le compte rendu du chef, tel que replacé dans son contexte, est un ajout important à notre connaissance du processus des traités numérotés dans l’Ouest canadien. -

Lt. Aemilius Simpson's Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society August 2014 Lt. Aemilius Simpson’s Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826 Edited by William Barr1 and Larry Green CONTENTS PREFACE The journal 2 Editorial practices 3 INTRODUCTION The man, the project, its background and its implementation 4 JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE ACROSS THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA IN 1826 York Factory to Norway House 11 Norway House to Carlton House 19 Carlton House to Fort Edmonton 27 Fort Edmonton to Boat Encampment, Columbia River 42 Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver 62 AFTERWORD Aemilius Simpson and the Northwest coast 1826–1831 81 APPENDIX I Biographical sketches 90 APPENDIX II Table of distances in statute miles from York Factory 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1. George Simpson, 1857 3 Fig. 2. York Factory 1853 4 Fig. 3. Artist’s impression of George Simpson, approaching a post in his personal North canoe 5 Fig. 4. Fort Vancouver ca.1854 78 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. York Factory to the Forks of the Saskatchewan River 7 Map 2. Carlton House to Boat Encampment 27 Map 3. Jasper to Fort Vancouver 65 1 Senior Research Associate, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary AB T2N 1N4 Canada. 2 PREFACE The Journal The journal presented here2 is transcribed from the original manuscript written in Aemilius Simpson’s hand. It is fifty folios in length in a bound volume of ninety folios, the final forty folios being blank. Each page measures 12.8 inches by seven inches and is lined with thirty- five faint, horizontal blue-grey lines. -

In Saskatchewan

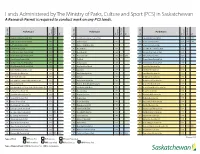

Lands Administered by The Ministry of Parks, Culture and Sport (PCS) in Saskatchewan A Research Permit is required to conduct work on any PCS lands. Park Name Park Name Park Name Type of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year HP Cannington Manor Provincial Park 1986 NE Saskatchewan Landing Provincial Park 1973 RP Crooked Lake Provincial Park 1986 PAA 2018 HP Cumberland House Provincial Park 1986 PR Anderson Island 1975 RP Danielson Provincial Park 1971 PAA 2018 HP Fort Carlton Provincial Park 1986 PR Bakken - Wright Bison Drive 1974 RP Echo Valley Provincial Park 1960 HP Fort Pitt Provincial Park 1986 PR Besant Midden 1974 RP Great Blue Heron Provincial Park 2013 HP Last Mountain House Provincial Park 1986 PR Brockelbank Hill 1992 RP Katepwa Point Provincial Park 1931 HP St. Victor Petroglyphs Provincial Park 1986 PR Christopher Lake 2000 PAA 2018 RP Pike Lake Provincial Park 1960 HP Steele Narrows Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Black 1974 RP Rowan’s Ravine Provincial Park 1960 HP Touchwood Hills Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Livingstone 1986 RP The Battlefords Provincial Park 1960 HP Wood Mountain Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Glen Ewen Burial Mound 1974 RS Amisk Lake Recreation Site 1986 HS Buffalo Rubbing Stone Historic Site 1986 PR Grasslands 1994 RS Arm River Recreation Site 1966 HS Chimney Coulee Historic Site 1986 PR Gray Archaeological Site 1986 RS Armit River Recreation Site 1986 HS Fort Pelly #1 Historic Site 1986 PR Gull Lake 1974 RS Beatty -

Saskatchewan 2015

seescenic SaSkatchewan 2015 get ready for fun Music festivals - heap on Spa serenity - the art of Scenic drives and forest the talent | P. 4 relaxation | P. 12 jewels | P. 34 TOuRism areas SaSkatoon what’s inside 08 | Local treasures, openly shared mooSe JaW 16 | Surprisingly unexpected central 20 | Remarkable places to discover NORTH 28 | Always more to explore REGINA 36 | There’s a lot to love SOUTh 40 | A destination for every imagination EVENTs 48 | 2015 Saskatchewan calendar 4 28 34 36 Publisher: Shaun Jessome Advertising director: Kelly Berg MArketing MAnAger: Jack Phipps music Festivals scenic drives and Art director: Michelle Houlden Heap on the talent for forest jewels Layout designer: Shelley Wichmann Production suPervisor: Robert Magnell 2015 | 4 Narrow Hills | 34 freelAnce And editoriAl content: spa serenity Golfing Cheryl Krett, Jesse Green, Amy Stewart-Nunn, The art of relaxation. | 12 Alison Barton, Candis Kirkpatrick, Robin and Juniors, seniors, novices, Arlene Karpan duffers or even scratch golfers can find plenty of venues in Photography: Christalee Froese, Robin and Saskatchewan. | 46 Arlen Karpan, Candis Kirkpatrick, David Venne Photography, Cheryl Krett, JazzFest Regina, Tourism Saskatoon Tourism Saskatchewan Greg Huszar Photography Douglas E. Walker Eric Lindberg Paul Austring J. F. Bergeron/Enviro Fotos Rob Weitzel Graphic Productions Kevin Hogarth Larry Goodfellow Cheryl Chase Hans Gerard-Pfaff Manitou Springs Resort & Mineral Spa Advertising: 1-888-820-8555 Western Producer Co-op Sales: Neale Buettner Ext 4 Laurie Michalycia Ext 1 Catherine Wrennick Ext 3 Fax: 306-653-8750 See Scenic Saskatchewan is a supplement to ON THE COVER: Wakeboarding at Great Blue The Western Producer, PO Box 2500 Station Heron Provincial Park | Tourism saskaTchewan/GreG Main, 2310 Millar Ave. -

Les Michif Aski ~ Métis and the Land. Perceptions of the Influence of Space and Place on Aging Well in Île-À-La-Crosse

Les Michif Aski ~ Métis and the Land. Perceptions of the Influence of Space and Place on Aging Well in Île-à-la-Crosse A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of Geography and Planning University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Canada By Boabang Owusu ©Copyright Boabang Owusu, December 2020. All Rights Reserved. Unless otherwise noted, copyright of the material in this thesis belongs to the author PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in the partial fulfillment of the requirement for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the head of the Department of Geography and Planning or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use, which may be made of any material in my thesis. I certify that the version I submitted is the same as that approved by my advisory committee. Requests for permission to copy