Tick-Borne Rickettsioses in International Travellers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution of Tick-Borne Diseases in China Xian-Bo Wu1, Ren-Hua Na2, Shan-Shan Wei2, Jin-Song Zhu3 and Hong-Juan Peng2*

Wu et al. Parasites & Vectors 2013, 6:119 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/6/1/119 REVIEW Open Access Distribution of tick-borne diseases in China Xian-Bo Wu1, Ren-Hua Na2, Shan-Shan Wei2, Jin-Song Zhu3 and Hong-Juan Peng2* Abstract As an important contributor to vector-borne diseases in China, in recent years, tick-borne diseases have attracted much attention because of their increasing incidence and consequent significant harm to livestock and human health. The most commonly observed human tick-borne diseases in China include Lyme borreliosis (known as Lyme disease in China), tick-borne encephalitis (known as Forest encephalitis in China), Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (known as Xinjiang hemorrhagic fever in China), Q-fever, tularemia and North-Asia tick-borne spotted fever. In recent years, some emerging tick-borne diseases, such as human monocytic ehrlichiosis, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and a novel bunyavirus infection, have been reported frequently in China. Other tick-borne diseases that are not as frequently reported in China include Colorado fever, oriental spotted fever and piroplasmosis. Detailed information regarding the history, characteristics, and current epidemic status of these human tick-borne diseases in China will be reviewed in this paper. It is clear that greater efforts in government management and research are required for the prevention, control, diagnosis, and treatment of tick-borne diseases, as well as for the control of ticks, in order to decrease the tick-borne disease burden in China. Keywords: Ticks, Tick-borne diseases, Epidemic, China Review (Table 1) [2,4]. Continuous reports of emerging tick-borne Ticks can carry and transmit viruses, bacteria, rickettsia, disease cases in Shandong, Henan, Hebei, Anhui, and spirochetes, protozoans, Chlamydia, Mycoplasma,Bartonia other provinces demonstrate the rise of these diseases bodies, and nematodes [1,2]. -

Babela Massiliensis, a Representative of a Widespread Bacterial

Babela massiliensis, a representative of a widespread bacterial phylum with unusual adaptations to parasitism in amoebae Isabelle Pagnier, Natalya Yutin, Olivier Croce, Kira S Makarova, Yuri I Wolf, Samia Benamar, Didier Raoult, Eugene V. Koonin, Bernard La Scola To cite this version: Isabelle Pagnier, Natalya Yutin, Olivier Croce, Kira S Makarova, Yuri I Wolf, et al.. Babela mas- siliensis, a representative of a widespread bacterial phylum with unusual adaptations to parasitism in amoebae. Biology Direct, BioMed Central, 2015, 10 (13), 10.1186/s13062-015-0043-z. hal-01217089 HAL Id: hal-01217089 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01217089 Submitted on 19 Oct 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Pagnier et al. Biology Direct (2015) 10:13 DOI 10.1186/s13062-015-0043-z RESEARCH Open Access Babela massiliensis, a representative of a widespread bacterial phylum with unusual adaptations to parasitism in amoebae Isabelle Pagnier1, Natalya Yutin2, Olivier Croce1, Kira S Makarova2, Yuri I Wolf2, Samia Benamar1, Didier Raoult1, Eugene V Koonin2 and Bernard La Scola1* Abstract Background: Only a small fraction of bacteria and archaea that are identifiable by metagenomics can be grown on standard media. -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

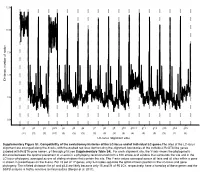

LC-Locus Alignment Sites Distance, Number of Nodes Supplementary

12.5 10.0 7.5 5.0 Distance, number of nodes 2.5 0.0 g1 g2 g3 g3.5 g4 g5 g6 g7 g8 g9 g10 g10.1 g11 g12 g13 g14 g15 (11) (3) (3) (10) (3) (3) (3) (3) (3) (3) (3) (4) (3) (3) (3) (2) (3) LC-locus alignment sites Supplementary Figure S1. Compatibility of the evolutionary histories of the LC-locus and of individual LC genes.The sites of the LC-locus alignment are arranged along the X-axis, with the dashed red lines demarcating the alignment boundaries of the individual RcGTA-like genes (labeled with RcGTA gene names, g1 through g15; see Supplementary Table S4). For each alignment site, the Y-axis shows the phylogenetic distance between the optimal placement of a taxon in a phylogeny reconstructed from a 100 amino-acid window that surrounds the site and in the LC-locus phylogeny, averaged across all sliding windows that contain the site. The Y-axis values averaged across all taxa and all sites within a gene is shown in parentheses on the X-axis. For 15 out of 17 genes, only 2-4 nodes separate the optimal taxon position in the LC-locus and gene phylogeny. The inflated distances for g1 and g3.5 are likely because only 15 and 21 of 95 LCs, respectively, have a homolog of these genes and the SSPB analysis is highly sensitive to missing data (Berger et al. 2011). a. Bacteria Unassigned Thermotogae Tenericutes Synergistetes Spirochaetes Proteobacteria ylum Planctomycetes h p Firmicutes Deferribacteres Cyanobacteria Chloroflexi Bacteroidetes Actinobacteria Acidobacteria 1(11,750) 2(1,750) 3(2,538) 4(168) 5(51) 6(54) 7(43) 8(32) 9(26) 10(40) 11(33) 12(198) 13(173) 14(101) 15(98) 16(43) 17(114) Number of rcc01682−rcc01698 homologs in a cluster b. -

Ohio Department of Health, Bureau of Infectious Diseases Disease Name Class A, Requires Immediate Phone Call to Local Health

Ohio Department of Health, Bureau of Infectious Diseases Reporting specifics for select diseases reportable by ELR Class A, requires immediate phone Susceptibilities specimen type Reportable test name (can change if Disease Name other specifics+ call to local health required* specifics~ state/federal case definition or department reporting requirements change) Culture independent diagnostic tests' (CIDT), like BioFire panel or BD MAX, E. histolytica Stain specimen = stool, bile results should be sent as E. histolytica DNA fluid, duodenal fluid, 260373001^DETECTED^SCT with E. histolytica Antigen Amebiasis (Entamoeba histolytica) No No tissue large intestine, disease/organism-specific DNA LOINC E. histolytica Antibody tissue small intestine codes OR a generic CIDT-LOINC code E. histolytica IgM with organism-specific DNA SNOMED E. histolytica IgG codes E. histolytica Total Antibody Ova and Parasite Anthrax Antibody Anthrax Antigen Anthrax EITB Acute Anthrax EITB Convalescent Anthrax Yes No Culture ELISA PCR Stain/microscopy Stain/spore ID Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus Antibody Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus IgG Antibody Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus IgM Arboviral neuroinvasive and non- Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus RNA neuroinvasive disease: Eastern equine California serogroup virus Antibody encephalitis virus disease; LaCrosse Equivocal results are accepted for all California serogroup virus IgG Antibody virus disease (other California arborviral diseases; California serogroup virus IgM Antibody specimen = blood, serum, serogroup -

Gene Gain and Loss Events in Rickettsia and Orientia Species Kalliopi Georgiades1,2, Vicky Merhej1, Khalid El Karkouri1, Didier Raoult1, Pierre Pontarotti2*

Georgiades et al. Biology Direct 2011, 6:6 http://www.biology-direct.com/content/6/1/6 RESEARCH Open Access Gene gain and loss events in Rickettsia and Orientia species Kalliopi Georgiades1,2, Vicky Merhej1, Khalid El Karkouri1, Didier Raoult1, Pierre Pontarotti2* Abstract Background: Genome degradation is an ongoing process in all members of the Rickettsiales order, which makes these bacterial species an excellent model for studying reductive evolution through interspecies variation in genome size and gene content. In this study, we evaluated the degree to which gene loss shaped the content of some Rickettsiales genomes. We shed light on the role played by horizontal gene transfers in the genome evolution of Rickettsiales. Results: Our phylogenomic tree, based on whole-genome content, presented a topology distinct from that of the whole core gene concatenated phylogenetic tree, suggesting that the gene repertoires involved have different evolutionary histories. Indeed, we present evidence for 3 possible horizontal gene transfer events from various organisms to Orientia and 6 to Rickettsia spp., while we also identified 3 possible horizontal gene transfer events from Rickettsia and Orientia to other bacteria. We found 17 putative genes in Rickettsia spp. that are probably the result of de novo gene creation; 2 of these genes appear to be functional. On the basis of these results, we were able to reconstruct the gene repertoires of “proto-Rickettsiales” and “proto-Rickettsiaceae”, which correspond to the ancestors of Rickettsiales and Rickettsiaceae, respectively. Finally, we found that 2,135 genes were lost during the evolution of the Rickettsiaceae to an intracellular lifestyle. Conclusions: Our phylogenetic analysis allowed us to track the gene gain and loss events occurring in bacterial genomes during their evolution from a free-living to an intracellular lifestyle. -

High Prevalence of Rickettsia Africae Variants in Amblyomma Variegatum Ticks from Domestic Mammals in Rural Western Kenya: Implications for Human Health

n Maina, A. N. et al. (2014) High prevalence of Rickettsia africae variants in Amblyomma variegatum ticks from domestic mammals in rural western Kenya: implications for human health. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 14 (10). pp. 693-702. ISSN 1530-3667 Copyright © 2014 The Authors http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/99480/ Deposited on: 17 November 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk VECTOR-BORNE AND ZOONOTIC DISEASES Volume 14, Number 10, 2014 ORIGINAL ARTICLES ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/vbz.2014.1578 High Prevalence of Rickettsia africae Variants in Amblyomma variegatum Ticks from Domestic Mammals in Rural Western Kenya: Implications for Human Health Alice N. Maina,1–3 Ju Jiang,3 Sylvia A. Omulo,2 Sally J. Cutler,4 Fredrick Ade,2 Eric Ogola,2 Daniel R. Feikin,5 M. Kariuki Njenga,5 Sarah Cleaveland,6 Solomon Mpoke,1,2 Zipporah Ng’ang’a,1 Robert F. Breiman,5 Darryn L. Knobel,2,7 and Allen L. Richards3 Abstract Tick-borne spotted fever group (SFG) rickettsioses are emerging human diseases caused by obligate intracel- lular Gram-negative bacteria of the genus Rickettsia. Despite being important causes of systemic febrile illnesses in travelers returning from sub-Saharan Africa, little is known about the reservoir hosts of these pathogens. We conducted surveys for rickettsiae in domestic animals and ticks in a rural setting in western Kenya. Of the 100 serum specimens tested from each species of domestic ruminant 43% of goats, 23% of sheep, and 1% of cattle had immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to the SFG rickettsiae. -

Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2020 Report to Congress

2nd Report Supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services • Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2020 Report to Congress Information and opinions in this report do not necessarily reflect the opinions of each member of the Working Group, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or any other component of the Federal government. Table of Contents Executive Summary . .1 Chapter 4: Clinical Manifestations, Appendices . 114 Diagnosis, and Diagnostics . 28 Chapter 1: Background . 4 Appendix A. Tick-Borne Disease Congressional Action ................. 8 Chapter 5: Causes, Pathogenesis, Working Group .....................114 and Pathophysiology . 44 The Tick-Borne Disease Working Group . 8 Appendix B. Tick-Borne Disease Working Chapter 6: Treatment . 51 Group Subcommittees ...............117 Second Report: Focus and Structure . 8 Chapter 7: Clinician and Public Appendix C. Acronyms and Abbreviations 126 Chapter 2: Methods of the Education, Patient Access Working Group . .10 to Care . 59 Appendix D. 21st Century Cures Act ...128 Topic Development Briefs ............ 10 Chapter 8: Epidemiology and Appendix E. Working Group Charter. .131 Surveillance . 84 Subcommittees ..................... 10 Chapter 9: Federal Inventory . 93 Appendix F. Federal Inventory Survey . 136 Federal Inventory ....................11 Chapter 10: Public Input . 98 Appendix G. References .............149 Minority Responses ................. 13 Chapter 11: Looking Forward . .103 Chapter 3: Tick Biology, Conclusion . 112 Ecology, and Control . .14 Contributions U.S. Department of Health and Human Services James J. Berger, MS, MT(ASCP), SBB B. Kaye Hayes, MPA Working Group Members David Hughes Walker, MD (Co-Chair) Adalbeto Pérez de León, DVM, MS, PhD Leigh Ann Soltysiak, MS (Co-Chair) Kevin R. -

Volume - I Ii Issue - Xxviii Jul / Aug 2008

VOLUME - I II ISSUE - XXVIII JUL / AUG 2008 With a worldwide footprint, Rickettsiosis are diseases that are gaining increasing significance as important causes of morbidity and to an extent mortality too. Encompassed within these are two main groups, viz., Rickettsia spotted fever group and the Typhus group (they differ in their surface exposed protein and lipopolysaccharide antigens). A unique thing about these organisms is that, though they are gram-negative bacilli, they 1 Editorial cannot be cultured in the traditional ways that we employ to culture regular bacteria. They Disease need viable eukaryotic host cells and they require a vector too to complete their run up to 2 Diagnosis the human host. Asia can boast of harbouring Epidemic typhus, Scrub typhus, Boutonneuse fever, North Asia Tick typhus, Oriental spotted fever and Q fever. The Interpretation pathological feature in most of these fevers is involvement of the microvasculature 6 (vasculitis/ perivasculitis at various locations). Most often, the clinical presentation initially Trouble is like Pyrexia of Unknown Origin. As they can't be cultured by the routine methods, the 7 Shooting diagnostic approach left is serological assays. A simple to perform investigation is the Weil-Felix reaction that is based on the cross-reactive antigens of OX-19 and OX-2 strains 7 Bouquet of Proteus vulgaris. Diagnosed early, Rickettsiae can be effectively treated by the most basic antibiotics like tetracyclines/ doxycycline and chloramphenicol. Epidemiologically almost omnipresent, the DISEASE DIAGNOSIS segment of this issue comprehensively 8 Tulip News discusses Rickettsiae. Vector and reservoir control, however, is the best approach in any case. -

Wholly Rickettsia! Reconstructed Metabolic Profile of the Quintessential Bacterial Parasite of Eukaryotic Cells

Faculty Scholarship 2017 Wholly Rickettsia! Reconstructed Metabolic Profile of the Quintessential Bacterial Parasite of Eukaryotic Cells Timothy P. Driscoll Victoria I. Verhoeve Mark L. Guillotte Stephanie S. Lehman Sherri A. Rennoll See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/faculty_publications Authors Timothy P. Driscoll, Victoria I. Verhoeve, Mark L. Guillotte, Stephanie S. Lehman, Sherri A. Rennoll, Magda Beier-Sexton, M Sayeedur Rahman, Abdu F. Azad, and Joseph J. Gillespie RESEARCH ARTICLE crossm Wholly Rickettsia! Reconstructed Metabolic Profile of the Quintessential Bacterial Parasite of Eukaryotic Cells Timothy P. Driscoll,a Victoria I. Verhoeve,a Mark L. Guillotte,b Stephanie S. Lehman,b Sherri A. Rennoll,b Magda Beier-Sexton,b Downloaded from M. Sayeedur Rahman,b Abdu F. Azad,b Joseph J. Gillespieb Department of Biology, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia, USAa; Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USAb ABSTRACT Reductive genome evolution has purged many metabolic pathways Received 21 May 2017 Accepted 15 August from obligate intracellular Rickettsia (Alphaproteobacteria; Rickettsiaceae). While some 2017 Published 26 September 2017 aspects of host-dependent rickettsial metabolism have been characterized, the array Citation Driscoll TP, Verhoeve VI, Guillotte ML, of host-acquired metabolites and their cognate transporters remains unknown. This Lehman SS, Rennoll SA, Beier-Sexton M, http://mbio.asm.org/ Rahman MS, Azad AF, Gillespie JJ. 2017. Wholly dearth of information has thwarted efforts to obtain an axenic Rickettsia culture, Rickettsia! Reconstructed metabolic profile of a major impediment to conventional genetic approaches. Using phylogenomics the quintessential bacterial parasite of and computational pathway analysis, we reconstructed the Rickettsia metabolic eukaryotic cells. -

“Epidemiology of Rickettsial Infections”

6/19/2019 I have got 45 min…… First 15 min… •A travel medicine physician… •Evolution of epidemiology of rickettsial diseases in brief “Epidemiology of rickettsial •Expanded knowledge of rickettsioses vs travel medicine infections” •Determinants of Current epidemiology of Rickettsialinfections •Role of returning traveller in rickettsial diseaseepidemiology Ranjan Premaratna •Current epidemiology vs travel health physician Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya Next 30 min… SRI LANKA •Clinical cases 12 Human Travel & People travel… Human activity Regionally and internationally Increased risk of contact between Bugs travel humans and bugs Deforestation Regionally and internationally Habitat fragmentation Echo tourism 34 This man.. a returning traveler.. down Change in global epidemiology with fever.. What can this be??? • This is the greatest challenge faced by an infectious disease / travel medicine physician • compared to a physician attending to a well streamlined management plan of a non-communicable disease……... 56 1 6/19/2019 Rickettsial diseases • A travel medicine physician… • Represent some of the oldest and most recently recognizedinfectious • Evolution of epidemiology of rickettsial diseases in brief diseases • Expanded knowledge of rickettsioses vs travel medicine • Determinants of Current epidemiology of Rickettsialinfections • Athens plague described during 5th century BC……? Epidemic typhus • Role of returning traveller in rickettsial diseaseepidemiology • Current epidemiology vs travel health physician • Clinical cases 78 In 1916.......... By 1970s-1980s four endemic rickettsioses; a single agent unique to a given geography !!! • R. prowazekii was identified as the etiological agent of epidemic typhus • Rocky Mountain spotted fever • Mediterranean spotted fever • North Asian tick typhus • Queensland tick typhus Walker DH, Fishbein DB. Epidemiology of rickettsial diseases. Eur J Epidemiol 1991 910 Family Rickettsiaceae Transitional group between SFG and TG Genera Rickettsia • R. -

Laboratory Diagnostics of Rickettsia Infections in Denmark 2008–2015

biology Article Laboratory Diagnostics of Rickettsia Infections in Denmark 2008–2015 Susanne Schjørring 1,2, Martin Tugwell Jepsen 1,3, Camilla Adler Sørensen 3,4, Palle Valentiner-Branth 5, Bjørn Kantsø 4, Randi Føns Petersen 1,4 , Ole Skovgaard 6,* and Karen A. Krogfelt 1,3,4,6,* 1 Department of Bacteria, Parasites and Fungi, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (M.T.J.); [email protected] (R.F.P.) 2 European Program for Public Health Microbiology Training (EUPHEM), European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), 27180 Solnar, Sweden 3 Scandtick Innovation, Project Group, InterReg, 551 11 Jönköping, Sweden; [email protected] 4 Virus and Microbiological Special Diagnostics, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] 5 Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] 6 Department of Science and Environment, Roskilde University, 4000 Roskilde, Denmark * Correspondence: [email protected] (O.S.); [email protected] (K.A.K.) Received: 19 May 2020; Accepted: 15 June 2020; Published: 19 June 2020 Abstract: Rickettsiosis is a vector-borne disease caused by bacterial species in the genus Rickettsia. Ticks in Scandinavia are reported to be infected with Rickettsia, yet only a few Scandinavian human cases are described, and rickettsiosis is poorly understood. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of rickettsiosis in Denmark based on laboratory findings. We found that in the Danish individuals who tested positive for Rickettsia by serology, the majority (86%; 484/561) of the infections belonged to the spotted fever group.