S Ection 2 S Ection 2 Finding S on Th E External Env Ironments Env

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hilton Istanbul Bomonti Hotel & Conference Center

Hilton Istanbul Bomonti Hotel & Conference Center Silahsor Caddesi No:42 I Bomonti Sisli Istanbul, 34381 Ph: +90 212 375 3000 Fax: +90 212 375 3001 BREAKFAST PLATED MENUS HEALTHY BREAKFAST TURKISH FEAST Baker’s Basket Baker’s Basket Whole-Wheat Rolls, Wasa Bread and Rye Toast with Low- "Simit", "Pide", Somun Bread, "Açma", "Poğaça" Sugar Marmalade, Honey and Becel Butter "Kaşar" Cheese, Feta Cheese, "Van Otlu" Cheese, "Pastırma", Eggs "Sucuk", Tomato, Cucumber, Honey, Clotted Cream, Egg White Frittata with Spinach and Tomato Accompanied by Marinated Green and Black Olives Sliced Oranges "Menemen" Swiss Bircher Muesli with Apricots, Cranberries, Apples and Scrambled Eggs with Peppers, Onion and Tomato Almonds Accompanied by Grilled Turkish "Sucuk" and Hash Browns AMERICAN BREAKFAST Baker’s Basket White and Brown Bread Rolls, Butter and Chocolate Croissants, Danish Pastry Marmalade, Honey, Butter and Margarine Eggs Scrambled Eggs on Toast, Accompanied by Veal and Chicken Sausages, Ham and Hash Browns Yoghurt Topped with Sliced Seasonal Fruits Hilton Istanbul Bomonti Hotel & Conference Center Silahsor Caddesi No:42 I Bomonti Sisli Istanbul, 34381 Ph: +90 212 375 3000 Fax: +90 212 375 3001 BREAKFAST BUFFET MENUS BREAKFAST AT HILTON BOMONTI Assorted Juice Turkish Breakfast Corner: Assorted Turkish Cheese Platter, Dil, Van Otlu, White Cheese Spinach "Börek", Cheese "Börek" Marinated Sun Dried Tomatoes in Olive Oil with Capers Turkish Black Olives Marinated with Spicy Peppers & Rosemary Turkish Green Olives with Roasted Capsicum and Eggplant, -

South African Food-Based Dietary Guidelines

ISSN 1607-0658 Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for South Africa S Afr J Clin Nutr 2013;26(3)(Supplement):S1-S164 FBDG-SA 2013 www.sajcn.co.za Developed and sponsored by: Distribution of launch issue sponsored by ISSN 1607-0658 Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for South Africa S Afr J Clin Nutr 2013;26(3)(Supplement):S1-S164 FBDG-SA 2013 www.sajcn.co.za Table of contents Cited as: Vorster HH, Badham JB, Venter CS. An 9. “Drink lots of clean, safe water”: a food-based introduction to the revised food-based dietary guidelines dietary guideline for South Africa Van Graan AE, Bopape M, Phooko D, for South Africa. S Afr J Clin Nutr 2013;26(3):S1-S164 Bourne L, Wright HH ................................................................. S77 Guest Editorial 10. The importance of the quality or type of fat in the diet: a food-based dietary guideline for South Africa • Revised food-based dietary guidelines for South Africa: Smuts CM, Wolmarans P.......................................................... S87 challenges pertaining to their testing, implementation and evaluation 11. Sugar and health: a food-based dietary guideline Vorster HH .................................................................................... S3 for South Africa Temple NJ, Steyn NP .............................................................. S100 Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for South Africa 12. “Use salt and foods high in salt sparingly”: a food-based dietary guideline for South Africa 1. An introduction to the revised food-based dietary Wentzel-Viljoen E, Steyn K, Ketterer E, Charlton KE ............ S105 guidelines for South Africa Vorster HH, Badham JB, Venter CS ........................................... S5 13. “If you drink alcohol, drink sensibly.” Is this 2. “Enjoy a variety of foods”: a food-based dietary guideline still appropriate? guideline for South Africa Jacobs L, Steyn NP................................................................ -

Visual Consumption: an Exploration of Narrative and Nostalgia in Contemporary South African Cookbooks

Visual consumption: an exploration of narrative and nostalgia in contemporary South African cookbooks by Francois Roelof Engelbrecht 92422013 A mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium (Information Design) in the Department of Visual Arts at the UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES MAY 2013 Supervisor: Prof J van Eeden © University of Pretoria DECLARATION I declare that Visual consumption: an exploration of narrative and nostalgia in contemporary South African cookbooks is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. __________________ Francois Engelbrecht Student number 92422013 6 May 2013 ii © University of Pretoria “What is patriotism but the love of the food one ate as a child?” – Lin Yutang (Lin Yutang > Quotes [sa]) iii © University of Pretoria SUMMARY AND KEY TERMS This study explores the visual consumption of food and its meanings through the study of narrative and nostalgia in a selection of five South African cookbooks. The aim of this study is to suggest, through the exploration of various cookbook narratives and the role that nostalgia plays in individual and collective identity formation and maintenance, that food, as symbolic goods, can act as a unifying ideology in the construction of a sense of national identity and nationhood. This is made relevant in a South African context through the analysis of a cross-section of five recent South African cookbooks. These are Shiny happy people (2009) by Neil Roake; Waar vye nog soet is (2009) by Emilia Le Roux and Francois Smuts; Evita’s kossie sikelela (2010) by Evita Bezuidenhout (Pieter-Dirk Uys); Tortoises & tumbleweeds (journey through an African kitchen) (2008) by Lannice Snyman; and South Africa eats (2009) by Phillippa Cheifitz. -

Affordable, Tasty Recipes

A JOINT INITIATIVE BY Compiled by Heleen Meyer Photography by Adriaan Vorster Affordable, tasty recipes – good for the whole family Foreword Contents Food is central to the identity of South Africans. How healthily do you eat? ...p2 The recipes in this book were During meals the family meets around the table. Guidelines for healthy eating ...p4 selected from family favourites On holidays and high days we gather around the Planning healthy meals ...p6 contributed by people all over braai and the potjie pot which reflect the diversity Takeaways and eating out ...p8 South Africa. These have been adapted to follow the guide - of our country. Food has many memories associated Frequently asked questions ...p10 lines of the Heart and Stroke with it – the soup that warms our bodies and our Shopping and cooking on a budget ...p12 Easy guide for reading food labels ...p13 Foundation South Africa. Re - souls, the dish for our homecomings, and the member that healthy eating is recipes that take us back to our youth. important for the whole family Recipes Food can also be our enemy. We are seeing rising levels of lifestyle diseases and not only for the person w in South Africa, with terrible impacts on our health – heart disease, stroke, A bowl of soup ...p14 affected by a lifestyle disease. type two diabetes and cancers are all on the rise, due to our increasingly w Salads and veggies ...p22 Teach your children to eat poor diet. w Lunch and supper ...p34 healthily from a young age to protect them from chronic • Fish ...p35 We all know that staying healthy can be difficult. -

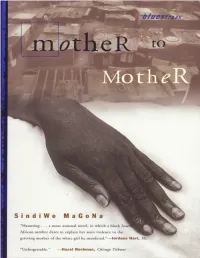

Wayeka Nokusenzel

FOR MY FATHER Author’s preface Fulbright scholar Amy Elizabeth Biehl was set upon and killed by a mob of black youth in Guguletu, South Africa, in August 1993. The outpouring of grief, outrage, and support for the Biehl family was unprecedented in the history of the country. Amy, a white American, had gone to South Africa to help black people prepare for the country’s rst truly democratic elections. Ironically, therefore, those who killed her were precisely the people for whom, by all subsequent accounts, she held a huge compassion, understanding the deprivations they had suered. Usually, and rightly, in situations such as this, we hear a lot about the world of the victim: his or her family, friends, work hobbies, hopes and aspirations. The Biehl case was no exception. And yet, are there no lessons to be had from knowing something of the other world? The reverse of such benevolent and nurturing entities as those that throw up the Amy Biehls, the Andrew Goodmans, and other young people of that quality? What was the world of this young women’s killers, the world of those, young as she was young, whose environment failed to nurture them in the higher ideals of humanity and who, instead, became lost creatures of malice and destruction? In my novel, there is only one killer. Through his mother’s memories, we get a glimpse of human callousness of the kind that made the murder of Amy Biehl possible. And here I am back in the legacy of apartheid — a system repressive and brutal, that bred senseless inter- and intra-racial violence as well as other nefarious happenings; a system that promoted a twisted sense of right and wrong, with everything seen through the warped prism of the overarching crime against humanity, as the international community labelled it. -

The Development of a Musical to Implement the Food

UTILISATION OF TRADITIONAL AND INDIGENOUS FOODS IN THE NORTH WEST PROVINCE OF SOUTH AFRICA SARAH T.P. MATENGE (M. Consumer Sciences) Thesis submitted for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Consumer Sciences at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University Promoter: Prof. A. Kruger Co-promoter: Prof. M. van der Merwe Co-promoter: Dr. H. de Beer POTCHEFSTROOM 2011 DEDICATIONS This thesis is dedicated to: My beloved parents, Johnson Matenge and Tsholofelo Matenge who taught me how to persevere and always have hope for better outcomes in the unpredictable future. Thanks again for your guidance and patience. I love you so much. To my children, Tapiwa and Tawanda, leaving you at a time when you needed me the most was the hardest thing that I had to do in my life, but I thank the omnipresent God who is watching over you and because of him you coped reasonably well. My son Panashe, has given me sincere love and support, has endured well the tough life in Potchefstroom and has been doing a good job at school. Just one look in his eyes gave me hope. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is evident that this thesis is a product of joint efforts from many people. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the following people who have contributed to make this study possible: Prof. A. Kruger, my promoter for her profound knowledge and her ability to see things in a bigger picture. Thanks for the hard work you have done as a supervisor. Prof. M. van der Merwe, co-promoter for her excellent guidance, expertise and selfless dedication. -

DISSERTATION O Attribution

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za (Accessed: Date). TEACHERS' EXPERIENCES OF INCORPORATING INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE IN THE LIFE SCIENCES CLASSROOM UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG by LIBRARY ANDJNFORMATION CENTRE campus: ~.t.c;, . MELIDA MODIANE MOTHWJ FacultylOept: :fk.(.;c~l~g,.~ . Selector:.:.:..:;.:.:. Shelf No: •• !.Ii 2eq.:.. ?1.,q.1!.~.f:?~ . /J7o -rr{ Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF SCIENCE EDUCATION to the FACULTY OF EDUCATION at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG SUPERVISOR: DR JJJ DE BEER CO- SUPERVISOR: DR U RAMNARAIN NOVEMBER 2011 DECLARATION I declare that the work contained in this dissertation is my own and all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of references. I also declare that I have not previously submitted this dissertation or any part of it to any university in order to obtain a degree. (Meiida M. Mothwa) Johannesburg November 2011 11 ACNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to dedicate this study to my determined and dedicated husband, Lesiba Edward, who was with me despite all the odds. -

Soweto, the S“ Torybook Place”: Tourism and Feeling in a South African Township Sarah Marie Kgagudi University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Soweto, The s“ torybook Place”: Tourism And Feeling In A South African Township Sarah Marie Kgagudi University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Linguistics Commons, Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Kgagudi, Sarah Marie, "Soweto, The s“ torybook Place”: Tourism And Feeling In A South African Township" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3320. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3320 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3320 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Soweto, The s“ torybook Place”: Tourism And Feeling In A South African Township Abstract This dissertation deals with the role of tour guides in creating and telling the story of Soweto – a township southwest of Johannesburg, South Africa. The ts ory speaks of a place afflicted by poverty because of its history of segregation during apartheid but emerging out of these struggles to lead its nation in a post-apartheid culture. I argue that Soweto’s story was created out of a governmental mandate for the township to become one of Gauteng’s tourism locations, and out of a knowledge that the transformation story from apartheid to a ‘rainbow nation’ would not sell in this context. After being created, Soweto’s story was affirmed through urban branding strategies and distributed to tourism markets across the world. It is a storybook – a narrative with a beginning, a climax, and an ending; it is easily packaged, marketed and sold to individuals from across the world, and this is done through the senses and emotions. -

MEDIA KIT the Mykitchen Brand

MEDIA KIT The MyKitchen brand MyKitchen is a magazine that seeks to inspire your inner chef. Budget-friendly, educational and jam-packed with recipes and added value, MyKitchen is an essential, collectable magazine and a must-read for everyone, from those who already love to cook to those looking for some new inspiration in the kitchen. Each issue is jam-packed with recipes that are easy, cost-efficient and sure to please the whole family, as well as challenging new dishes to master and treats for special occasions. There are also tips on healthy eating, how-tos on tricky cooking methods and news on the latest foodie trends and culinary events. 2019 VISION MyKitchen aims to become the authority in home cooking, becoming the most popular guide to South Africans looking for budget, easy and inspirational dishes. Finding creative ways for readers to save money and cook delicious dishes will remain the core focus. MERIT WINNER (2018) 53RD ANNUAL ONE OF THE SPD AWARDS THE CONTENT COUNCIL THE CONTENT COUNCIL (SOCIETY OF TOP 5 HIGHEST PEARL AWARD PEARL AWARD PUBLICATION CIRCULATING CONSUMER SILVER AWARD: SILVER AWARD: DESIGNERS) BEST COVER 2018 BEST COVER 2017 (THE WORLD’S BEST EDITORIAL MAGAZINES IN SA (INTERNATIONAL DESIGN AWARD) (INTERNATIONAL DESIGN AWARD) DESIGN COMPETITION) (ABC: Q4 2017) The MyKitchen fact sheet Pick n Pay, Spar, RETAIL CALENDAR Key pillars Shoprite/Checkers, ALLOCATION Budget | Home Cooking | Health The following issues of Exclusive Books, MyKitchen will be Educational | Local Food CNA, OK, Friendly available in retail: -

Exploring Indigenous Knowledge Practices Concerning Health and Well-Being: a Case Study of Isixhosa-Speaking Women in the Rural Eastern Cape

Exploring Indigenous Knowledge Practices Concerning Health and Well-being: A Case Study of isiXhosa-speaking Women in the Rural Eastern Cape. BY: Helen Yolisa Hobongwana-Duley Thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the School of Education Graduate School of Humanities University of Cape Town Supervisors Dr. Linda Cooper UniversityDr. Salma Ismail of Cape Town Professor Crain Soudien July 2014 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. ii iii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Aaron and Monica Hobongwana and to my grandparents Wilson Kulile Hobongwana and Miriam Ntumpuse Hobongwana. iv ABSTRACT This thesis explores, analyzes and conceptualizes the indigenous knowledge practices concerning health and well-being held by different generations of women and how they are reproduced cross-generationally in a rural isiXhosa-speaking community. It also explores how the relationship between concepts of self, personhood and Ubuntu informs women’s agency. Additionally, this thesis explores how the indigenous knowledge practices might have the potential to augment inclusive and relevant tools for learning for young women, girls and youth. -

The Association of General and Central Obesity with Dietary Patterns and Socioeconomic Status in Adult Women in Botswana

Hindawi Journal of Obesity Volume 2020, Article ID 4959272, 10 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4959272 Research Article The Association of General and Central Obesity with Dietary Patterns and Socioeconomic Status in Adult Women in Botswana Boitumelo Motswagole ,1 Jose Jackson,2 Rosemary Kobue-Lekalake,3 Segametsi Maruapula,4 Tiyapo Mongwaketse,1 Lemogang Kwape,1,5 Tinku Thomas,6 Sumathi Swaminathan,6 Anura V. Kurpad,6 and Maria Jackson7 1National Food Technology Research Centre, Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Private Bag 8, Kanye, Botswana 2Michigan State University, Alliance for African Partnership, 427 N Shaw Lane, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA 3Botswana University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Department of Food Science and Technology, Private Bag, 0027 Gaborone, Botswana 4University of Botswana, Department of Family and Consumer Sciences, Private Bag, 0022 Gaborone, Botswana 5Ministry of Health & Wellness, Private Bag, 0038 Gaborone, Botswana 6St Johns Research Institute, Koramangala, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India 7University of the West Indies, Department of Community Health and Psychiatry, Kingston, Jamaica Correspondence should be addressed to Boitumelo Motswagole; [email protected] Received 9 August 2019; Revised 31 March 2020; Accepted 5 August 2020; Published 1 September 2020 Academic Editor: Aron Weller Copyright © 2020 Boitumelo Motswagole et al. )is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Dietary patterns and their association with general and central obesity among adult women were studied using a cross-sectional survey with multistage cluster sampling in urban and rural areas nationwide in Botswana. -

Master Menus

The Bayside Pantry Truly South African Buffet Experience Every Wednesday in September from 18h00 - 22h00 The Bayside Pantry Buffet Menu We regret no under 18's Book Now! Per Person R140.00 Soup of the Day Isophu (Samp and Bean Soup) Beef and Green Split Pea Soup Freshly Baked Breads and Rolls Roosterkoek Vetkoek Salads Build Your Own Salad Tossed leafy greens Cocktail tomato Feta cheese Sliced cucumber Red onion rings Diced beetroot Cajun chicken strips Sliced assorted peppers Diced cheddar cheese Diced mozzarella 4 Dressings Greek French Ranch Blue cheese Potato Salad Mpokoqo and Amasi (African Salad) Pasta Salad Coleslaw Chakalaka Salad with Beans Cape Malay Pickle Fish Peppered Mackerel Smoersnoek South African Cape Stir Fry Shrimp Sliced Onions Sliced Green Peppers Egg Noodles Fried Rice Chicken Strips Beef Ox Liver Seafood Mix Spinach Pineapple Julienne Carrots Stir Fry Vegetables Chicken Stock Garlic Oil Chilli Oil Soya Sauce Ginger Oil Bunny Chow Station Boneless Chicken Ccurry in a Quarter Loaf 3 Bean Curry in a Quarter Loaf Lamb Curry on a Quarter Loaf Braai Station Boerewors Skilpadjies Beef Chuck Carvery Station Roasted Whole Bird Lemon and Thyme Sticky Chicken Leg Quarters Roast Beef Topside Roast Potatoes Sauces: Mushroom sauce Plain gravy (jus) Apple sauce/mint sauce Horseradish From The Pots Umngqusho (Samp and Beans) Umfino (Spinach, Cabbage and Mielie Meal) Ithanga (Butternut with Cinnamon) Pap and Tomato Bistro Corn on the Cob Umsila Wenkomo (Oxtail Potjie with Waterblommetjies) Chicken Chakalaka Beef with Amadombolo