Better Things

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S Ection 2 S Ection 2 Finding S on Th E External Env Ironments Env

S ECTION 2 FINDING S ON TH E EXTERNAL ENV IRONMENTS AND EV ERYDAY FOOD P RACPRACRACTICESRACTICESTICESTICES INTRODUCTION This first section on the findings contains Chapters 4 and 5. In Chapter 4 the external environments of the participants are described. This includes not only an account of the geographical location and physical environment of Mmotla but also refers to important aspects of the socio-cultural environment of the participants. In Chapter 5 the everyday food practices of the participants are contextualised by giving a description of how they view and use food. The contemporary eating patterns as they are followed on weekdays and over weekends are reported on and interpreted. This section comprises two chapters entitled: Chapter 4: External environments of the participants Chapter 5: Everyday food practices CH AP TER 4 EXTERNAL ENV IRONMEIRONMENTSNTS OF TH E P ARTICIP ANTS 4.1 INTRODUCTION Human food choice always takes place within the boundaries of what food is available, accessible and acceptable to people and is primarily determined by the external environments in which they live as described in Chapter 2 (see 2.2.1). Each of these environments, namely the physical, economic, political and socio-cultural, provides both opportunities and constraints for human food consumption (Bryant et al., 2003:10). This exemplifies the contention that where people live contributes to their potential food choices (Kittler & Sucher, 2008:12; Bryant et al., 2003:11). In this first chapter on the findings of the study, the external environments of the participants are sketched to contextualise the contemporary food practices of the Mmotla community. -

Wayeka Nokusenzel

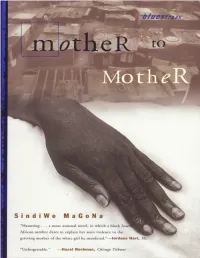

FOR MY FATHER Author’s preface Fulbright scholar Amy Elizabeth Biehl was set upon and killed by a mob of black youth in Guguletu, South Africa, in August 1993. The outpouring of grief, outrage, and support for the Biehl family was unprecedented in the history of the country. Amy, a white American, had gone to South Africa to help black people prepare for the country’s rst truly democratic elections. Ironically, therefore, those who killed her were precisely the people for whom, by all subsequent accounts, she held a huge compassion, understanding the deprivations they had suered. Usually, and rightly, in situations such as this, we hear a lot about the world of the victim: his or her family, friends, work hobbies, hopes and aspirations. The Biehl case was no exception. And yet, are there no lessons to be had from knowing something of the other world? The reverse of such benevolent and nurturing entities as those that throw up the Amy Biehls, the Andrew Goodmans, and other young people of that quality? What was the world of this young women’s killers, the world of those, young as she was young, whose environment failed to nurture them in the higher ideals of humanity and who, instead, became lost creatures of malice and destruction? In my novel, there is only one killer. Through his mother’s memories, we get a glimpse of human callousness of the kind that made the murder of Amy Biehl possible. And here I am back in the legacy of apartheid — a system repressive and brutal, that bred senseless inter- and intra-racial violence as well as other nefarious happenings; a system that promoted a twisted sense of right and wrong, with everything seen through the warped prism of the overarching crime against humanity, as the international community labelled it. -

Exploring Indigenous Knowledge Practices Concerning Health and Well-Being: a Case Study of Isixhosa-Speaking Women in the Rural Eastern Cape

Exploring Indigenous Knowledge Practices Concerning Health and Well-being: A Case Study of isiXhosa-speaking Women in the Rural Eastern Cape. BY: Helen Yolisa Hobongwana-Duley Thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the School of Education Graduate School of Humanities University of Cape Town Supervisors Dr. Linda Cooper UniversityDr. Salma Ismail of Cape Town Professor Crain Soudien July 2014 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. ii iii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Aaron and Monica Hobongwana and to my grandparents Wilson Kulile Hobongwana and Miriam Ntumpuse Hobongwana. iv ABSTRACT This thesis explores, analyzes and conceptualizes the indigenous knowledge practices concerning health and well-being held by different generations of women and how they are reproduced cross-generationally in a rural isiXhosa-speaking community. It also explores how the relationship between concepts of self, personhood and Ubuntu informs women’s agency. Additionally, this thesis explores how the indigenous knowledge practices might have the potential to augment inclusive and relevant tools for learning for young women, girls and youth. -

Musicians Have the Right to Broadcasting on 88.5 FM on 1 Ence at the Same Time

In The Zone Vol 1 April 2020 Who is Zone Radio? From Cape Town to the World South Africa in Lockdown The Do’s and Don’ts of lockdown Kiss my Chumbawamba So how exactly did bands get their names Whatever happened to... Remembering SA’s bands and artists The Voice of the Valley CONTENTS April 2020 Page 28 Page 22 Welcome To Shorties Blue Bottle Noordhoek Blue Bottle Liquors has been operating successfully since the year 2000. We carry huge ranges of wine, malt whiskies, and are geared for all functions. Our emphasis is on personal service in a safe environment, promoting responsible drinking. We pride ourselves in quality products. We haven’t left it there though!! We have now Kiss my Chumbawamba extended our operation and set up a Traders Association involving several very successful Every great band needs a great name. independent liquor stores who understand their customer’s needs and are extremely aware Page 28 of promoting responsible drinking. They have revamped their stores for a better, secure and informative shopping experience. Being part of the Blue Bottle membership means we offer 20 better prices, professional advice and don’t forget the personal touch of the owner. Features 40 Rainbow cuisine Two Grumpy Old Men 6 We look at some of South Afri- Matt and John are complaining So who is Zone Radio? ca’s traditional dishes. yet again. 24 Zone Radio has quickly estab- 42 lished themselves as “the voice Silver lining 10 essential foods of the valley”. But who exactly Click on the link on the left to Sometimes great things happen What you should be eating this is Zone Radio? as a result of terrible disasters. -

Omslag Report V2

The aflatoxin situation in Africa Systematic literature review RIKILT report 2018.010 The aflatoxin situation in Africa Systematic literature review Nathan Meijer 1, Gijs Kleter 1, Rosa Amalia Safitri 1, Monique de Nijs 1, Marie-Luise Rau 2, Ria Derkx 3, Joke Webbink 3, Marijn Post 3, Yuca Waarts 2, Ine van der Fels-Klerx 1 1 RIKILT Wageningen University & Research 2 Wageningen Economic Research 3 Wageningen University & Research - Library This research has been carried out by Wageningen University & Research and financed by Partnership for Aflatoxin Control in Africa (PACA) through funds made available to PACA by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Mars, Incorporated (project number 1277360301). PACA acknowledges the contribution of the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) in producing this report which is a follow up to the CTA/PACA 2016 Working Paper “Improving the evidence base on aflatoxin contamination and exposure in Africa” written by Sheila Okoth. Wageningen, December 2018 RIKILT report 2018.010 RIKILT report 2018.010 | 1 Project number: 1277360301 Project title: The aflatoxin situation in Africa Project leader: Nathan Meijer © 2018 African Union Commission / PACA. This study was financed by Partnership for Aflatoxin Control in Africa (PACA) through funds made available to PACA by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Mars, Incorporated. PACA acknowledges the contribution of the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) in producing this report which is a follow up to the CTA/PACA 2016 Working Paper “Improving the evidence base on aflatoxin contamination and exposure in Africa” written by Sheila Okoth. This report is published by RIKILT Wageningen University & Research, institute within the legal entity Wageningen Research Foundation with the copyright holder’s permission. -

The Current Rain-Fed and Irrigated Production of Food Crops and Its Potential to Meet

THE CURRENT RAIN-FED AND IRRIGATED PRODUCTION OF FOOD CROPS AND ITS POTENTIAL TO MEET THE YEAR-ROUND NUTRITIONAL REQUIREMENTS OF RURAL POOR PEOPLE IN NORTH WEST, LIMPOPO, KWAZULU-NATAL AND THE EASTERN CAPE Report to the WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION and DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY & FISHERIES by SL Hendriks, A Viljoen, D Marais, F Wenhold, AM McIntyre, MS Ngidi, C van der Merwe, J Annandale and M Kalaba Institute for Food, Nutrition and Well-being University of Pretoria with D Stewart Lima Rural Development Foundation WRC Report No. 2172/1/16 ISBN 978-1-4312-0836-4 September 2016 Obtainable from Water Research Commission Private Bag X03 Gezina, 0031 [email protected] or download from www.wrc.org.za DISCLAIMER This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approved it for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC or the University of Pretoria (UP), nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. © Water Research Commission & University of Pretoria ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY While there is not much evidence of widespread starvation and extreme undernutrition in South Africa, national surveys provide evidence of multiple forms of deprivation related to the experience of hunger, widespread manifestation of hidden hunger or micronutrient deficiencies and increasing rates of overweight and obesity. Moreover, the co-existence of adult (especially female) overweight and obesity with hidden hunger and child malnutrition raises serious concerns over household food security. Despite a multitude of state, private sector and non-governmental agency (NGO)-funded food security programmes, South Africa is one of only 12 countries in the world where stunting has increased over the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) period. -

Quelques Données Sur Des Points De Culture De Pays Anglophones

Quelques données sur des points de culture de pays anglophones I) Welcome to Australia a) The map Capital city: Canberra b) Australian flag Le drapeau de l'Australie est bleu avec, dans le quart supérieur gauche l'Union Jack. Au-dessous se trouve l'Étoile de la fédération (six branches, une pour chacun des six États : le Queensland, la Nouvelle-Galles du Sud, le Victoria, la Tasmanie, l'Australie-Méridionale et l'Australie-Occidentale, et une branche pour les deux territoires, le Territoire de la capitale australienne et le Territoire du Nord. L'autre moitié du drapeau représente la constellation de la Croix du Sud. c) Currency of Australia 1 Name: Australian Dollar Symbol:$, c Minor Unit: 1/100 = Cent Coins: $1, $2, 5c, 10c, 20c, 50c Banknotes: $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 d) National Anthem English French Australians all let us rejoice, For we are young Australiens réjouissons nous tous, and free; Car nous sommes jeunes et libres ; Nous avons un sol doré et de la richesse pour le We've golden soil and wealth for toil, Our home labeur, is girt by sea; Notre patrie est ceinte par la mer ; Our land abounds in Nature's gifts Notre terre abonde des cadeaux Of beauty rich and rare; de la nature D'une beauté riche et In history's page, let every stage Advance rare ; Australia fair! Dans le livre de l'histoire, qu'à chaque page In joyful strains then let us sing, Avance la belle et juste Australie ! « Advance Australia fair! » Aux tons joyeux chantons alors, « Avance belle et juste Australie ! » Beneath our radiant Southern Cross, We'll toil with -

Cross Border Themed Tourism Routes

CROSS-BORDER THEMED TOURISM ROUTES IN THE SOUTHERN AFRICAN REGION: PRACTICE AND POTENTIAL DEPARTMENT OF HERITAGE AND HISTORICAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA FINAL REPORT MARCH 2019 Table of Contents Page no. List of Abbreviations iii List of Definitions iv List of Tables vii List of Maps viii List of Figures ix SECTION 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT OF THE STUDY 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Background and Context 4 1.3 Problem Statement 6 1.4 Rational of the Study 7 1.5 Purpose of the Study 8 1.6 Research questions 8 1.7 Objectives of the Study 9 SECTION 2: RESEARC H METHOOLODY 10 2.1 Literature Survey 10 2.2 Data Collection 10 2.3 Data Analysis 11 2.4 Ethical Aspects 12 SECTION 3: THEORY ANF LITERATURE REVIEW 13 3.1 Theoretical Framework 13 3.2 Literature Review 15 SECTION 4: STAKEHOLDERS AND CROSS-BORDER TOURISM. 33 4.1 Introduction 33 4.2 Stakeholder Categories and Stakeholders 33 4.3 SADC Stakeholders 34 4.4 Government Bodies 35 4.5 The Tourism Industry 42 4.6 Tourists 53 4.7 Supplementary Group 56 SECTION 5: DIFFICULTIES OR CHALLENGES INVOLVED IN CBT 58 5.1 Introduction 58 i 5.2 Varied Levels of Development 59 5.3 Infrastructure 60 5.4 Lack of Coordination/Collaboration 64 5.5 Legislative/Regulatory Restrictions and Alignment 65 5.6 Language 70 5.7 Varied Currencies 72 5.8 Competitiveness 72 5.9 Safety and Security 76 SECTION 6 – SHORT TERM MITIGATIONS AND LONG TERM SOLUTIONS 77 6.1 Introduction 77 6.2 Collaboration and Partnership 77 6.3 Diplomacy/Supranational Agreements 85 6.4 Single Regional and Regionally Accepted Currency 87 6.5 Investment -

The Aflatoxin Situation in Africa

The aflatoxin situation in Africa Systematic literature review RIKILT report 2018.010 The aflatoxin situation in Africa Systematic literature review Nathan Meijer1, Gijs Kleter1, Rosa Amalia Safitri1, Monique de Nijs1, Marie-Luise Rau2, Ria Derkx3, Joke Webbink3, Marijn Post3, Yuca Waarts2, Ine van der Fels-Klerx1 1 RIKILT Wageningen University & Research 2 Wageningen Economic Research 3 Wageningen University & Research - Library This research has been carried out by Wageningen University & Research and financed by Partnership for Aflatoxin Control in Africa (PACA) through funds made available to PACA by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Mars, Incorporated (project number 1277360301). PACA acknowledges the contribution of the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) in producing this report which is a follow up to the CTA/PACA 2016 Working Paper “Improving the evidence base on aflatoxin contamination and exposure in Africa” written by Sheila Okoth. Wageningen, December 2018 RIKILT report 2018.010 RIKILT report 2018.010| 1 Project number: 1277360301 Project title: The aflatoxin situation in Africa Project leader: Nathan Meijer © 2018 African Union Commission / PACA. This study was financed by Partnership for Aflatoxin Control in Africa (PACA) through funds made available to PACA by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Mars, Incorporated. PACA acknowledges the contribution of the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) in producing this report which is a follow up to the CTA/PACA 2016 Working Paper “Improving the evidence base on aflatoxin contamination and exposure in Africa” written by Sheila Okoth. This report is published by RIKILT Wageningen University & Research, institute within the legal entity Wageningen Research Foundation with the copyright holder’s permission. -

Celtic Rumours (The White Zulu)

In The Zone Vol 1 April 2020 Who is Zone Radio? From Cape Town to the World South Africa in Lockdown The Do’s and Don’ts of lockdown Kiss my Chumbawamba So how exactly did bands get their names Whatever happened to... Remembering SA’s bands and artists The Voice of the Valley CONTENTS April 2020 Page 28 Page 22 Welcome To Shorties Blue Bottle Noordhoek Blue Bottle Liquors has been operating successfully since the year 2000. We carry huge ranges of wine, malt whiskies, and are geared for all functions. Our emphasis is on personal service in a safe environment, promoting responsible drinking. We pride ourselves in quality products. We haven’t left it there though!! We have now Kiss my Chumbawamba extended our operation and set up a Traders Association involving several very successful Every great band needs a great name. independent liquor stores who understand their customer’s needs and are extremely aware Page 28 of promoting responsible drinking. They have revamped their stores for a better, secure and informative shopping experience. Being part of the Blue Bottle membership means we offer 20 better prices, professional advice and don’t forget the personal touch of the owner. Features 40 Rainbow cuisine Two Grumpy Old Men 6 We look at some of South Afri- Matt and John are complaining So who is Zone Radio? ca’s traditional dishes. yet again. 24 Zone Radio has quickly estab- 42 lished themselves as “the voice Silver lining 10 essential foods of the valley”. But who exactly Click on the link on the left to Sometimes great things happen What you should be eating this is Zone Radio? as a result of terrible disasters. -

Analysis of the Bacterial Microbiome from Prostate Tissue of South African Men

Analysis of the Bacterial Microbiome from Prostate Tissue of South African Men Pieter Hendrik Bouwman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of M.Sc. Genetics in the Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, Department of Genetics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria July 2019 Supervisor: Prof DA Cowan Co-Supervisors: Dr A Valverde Prof MS Bornman Prof VM Hayes Abstract Cancer is a major cause of death globally and the incidence of the disease is expected to increase in coming years. It is predicted that 20 million new cases of cancer will be observed annually as early as 2025, rising from 14.1 million new cases in 2012. Prostate Cancer (PCa) was found to have the second highest incidence among male cancers globally, and it is expected that the absolute number of men with PCa will increase. Contrary to global trends, PCa has a higher incidence and mortality rate than lung cancer in Sub- Saharan African men. According to the National Cancer Registry of South Africa, the incidence of PCa was three times greater than the incidence of lung cancer amongst men in 2010. Furthermore, disparities have been reported in the presentation and outcomes of PCa between racial groups. PCa has been found to be more common amongst men with African ancestry, and Black South African men have been shown to present a more aggressive disease phenotype. The South African Prostate Cancer Study (SAPCS) was established in 2008 to investigate clinical presentation, epidemiological risk factors, and associated microbial pathogenic contributions to PCa within Black South Africans from rural and urban localities. -

Tshwane Travel Guide

Tshwane TravelGuide Journey in the footsteps of leaders and legends … Contents Welcome to the capital Compass to the capital Destination with a difference Journey of discovery of historical sites Giants of the past Meeting place of the world Lions roaming in this city! Let our rhythm move your soul Sport in our veins The terminus of global trade and travel Diplomatic capital Tourist information Safety tips 1 WelcometotheCapital “Panoramic” is the most appropriate word for the wide, Be warned that you will leave her embrace with a open vistas of Tshwane, the third largest city in the world yearning for her mesmerising hold on you – this city with with its whopping 6 368 km² lled with magnicent city the sparkle of the Cullinan diamond mine and village, and countryside views. the stateliness of the Union Buildings, the mysterious charm and spirit of freedom of Freedom Park, the depth Only 45 minutes after landing at OR Tambo Inter- of character anchored in her deep-rooted heritage, but national Airport the beauty of the capital will welcome most of all her colourful and hospitable people who you in her a green embrace. And should you be might have found a home in your heart. fortunate to visit her during spring she will wear her royal garment of purple jacaranda blooms. She will invite you Facts about Tshwane to stand on her historic hills and charm you with her scenic views from Freedom Park, the Voortrekker • The largest metropolitan municipality in South Monument, Fort Schanskop or Fort Klapperkop, to Africa mention only a few of her glorious sites.