The Current Rain-Fed and Irrigated Production of Food Crops and Its Potential to Meet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S Ection 2 S Ection 2 Finding S on Th E External Env Ironments Env

S ECTION 2 FINDING S ON TH E EXTERNAL ENV IRONMENTS AND EV ERYDAY FOOD P RACPRACRACTICESRACTICESTICESTICES INTRODUCTION This first section on the findings contains Chapters 4 and 5. In Chapter 4 the external environments of the participants are described. This includes not only an account of the geographical location and physical environment of Mmotla but also refers to important aspects of the socio-cultural environment of the participants. In Chapter 5 the everyday food practices of the participants are contextualised by giving a description of how they view and use food. The contemporary eating patterns as they are followed on weekdays and over weekends are reported on and interpreted. This section comprises two chapters entitled: Chapter 4: External environments of the participants Chapter 5: Everyday food practices CH AP TER 4 EXTERNAL ENV IRONMEIRONMENTSNTS OF TH E P ARTICIP ANTS 4.1 INTRODUCTION Human food choice always takes place within the boundaries of what food is available, accessible and acceptable to people and is primarily determined by the external environments in which they live as described in Chapter 2 (see 2.2.1). Each of these environments, namely the physical, economic, political and socio-cultural, provides both opportunities and constraints for human food consumption (Bryant et al., 2003:10). This exemplifies the contention that where people live contributes to their potential food choices (Kittler & Sucher, 2008:12; Bryant et al., 2003:11). In this first chapter on the findings of the study, the external environments of the participants are sketched to contextualise the contemporary food practices of the Mmotla community. -

Dietary Intake, Physical Activity and Risk for Chronic Diseases of Lifestyle Among Employees at a South African Open-Cast Diamond Mine

DIETARY INTAKE, PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND RISK FOR CHRONIC DISEASES OF LIFESTYLE AMONG EMPLOYEES AT A SOUTH AFRICAN OPEN-CAST DIAMOND MINE Thesis presented to the Department of Human Nutrition of the Stellenbosch University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Nutrition by Karen Stadler Study Leader: Prof. D Labadarios (Head: Department of Human Nutrition, Stellenbosch University) Co-study Leader: Prof MG Herselman (Associate Professor: Department of Human Nutrition, Stellenbosch University) Co-study Leader: Ms N Fredericks (Dietician, Tygerberg Hospital) Statistician: Prof DG Nel (Director: Center for Statistical Consultation, Stellenbosch University) Confidentiality: B April 2006 ii DECLARATION OF AUTHENTICITY Hereby I, Karen Stadler, declare that this thesis is my own original work and that all sources have been accurately reported and acknowledged, and that this document has not previously, in its entirety or in part been submitted at any university in order to obtain an academic qualification. Karen Stadler Date: 21 February 2006 iii ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION: The study investigated dietary intake, physical activity and risk for chronic diseases of lifestyle (CDL) among employees at a South African open-cast diamond mine. OBJECTIVES: The aim of the study was to determine the habits and barriers to a healthy lifestyle in order to determine the need for workplace interventions at De Beers Venetia Mine (DB-VM) to decrease the risk for CDL and optimise employee wellness. DESIGN: An analytical, cross-sectional, observational study. SAMPLING: A representative proportional stratified sample of 88 permanent employees at DB-VM was randomly selected to participate in the study. The sample was stratified according to work-shift configuration and occupational category. -

Student Number: 201477310

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Index?site_name=Research%20Output (Accessed: Date). Metabolomics, Physicochemical Properties and Mycotoxin Reduction of Whole Grain Ting (a Southern African fermented food) Produced via Natural and Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) fermentation A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Science, University of Johannesburg, South Africa In partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of a Doctoral Degree in Food Technology By OLUWAFEMI AYODEJI ADEBO STUDENT NUMBER: 201477310 Supervisor : Dr. E. Kayitesi Co-supervisor: Prof. P. B. Njobeh October 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Drought and challenges related to climate change are some of the issues facing sub-Saharan Africa countries, with dire consequences on agriculture and food security. Due to this prevailing situation, drought and climate resistant crops like sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L) Moench) can adequately contribute to food security. The versatility and importance of sorghum is well reflected in its use as a major food source for millions of people in sub-Saharan Africa. -

Wayeka Nokusenzel

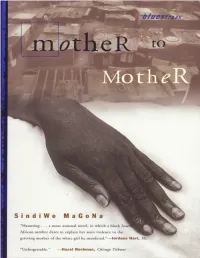

FOR MY FATHER Author’s preface Fulbright scholar Amy Elizabeth Biehl was set upon and killed by a mob of black youth in Guguletu, South Africa, in August 1993. The outpouring of grief, outrage, and support for the Biehl family was unprecedented in the history of the country. Amy, a white American, had gone to South Africa to help black people prepare for the country’s rst truly democratic elections. Ironically, therefore, those who killed her were precisely the people for whom, by all subsequent accounts, she held a huge compassion, understanding the deprivations they had suered. Usually, and rightly, in situations such as this, we hear a lot about the world of the victim: his or her family, friends, work hobbies, hopes and aspirations. The Biehl case was no exception. And yet, are there no lessons to be had from knowing something of the other world? The reverse of such benevolent and nurturing entities as those that throw up the Amy Biehls, the Andrew Goodmans, and other young people of that quality? What was the world of this young women’s killers, the world of those, young as she was young, whose environment failed to nurture them in the higher ideals of humanity and who, instead, became lost creatures of malice and destruction? In my novel, there is only one killer. Through his mother’s memories, we get a glimpse of human callousness of the kind that made the murder of Amy Biehl possible. And here I am back in the legacy of apartheid — a system repressive and brutal, that bred senseless inter- and intra-racial violence as well as other nefarious happenings; a system that promoted a twisted sense of right and wrong, with everything seen through the warped prism of the overarching crime against humanity, as the international community labelled it. -

Exploring Indigenous Knowledge Practices Concerning Health and Well-Being: a Case Study of Isixhosa-Speaking Women in the Rural Eastern Cape

Exploring Indigenous Knowledge Practices Concerning Health and Well-being: A Case Study of isiXhosa-speaking Women in the Rural Eastern Cape. BY: Helen Yolisa Hobongwana-Duley Thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the School of Education Graduate School of Humanities University of Cape Town Supervisors Dr. Linda Cooper UniversityDr. Salma Ismail of Cape Town Professor Crain Soudien July 2014 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. ii iii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Aaron and Monica Hobongwana and to my grandparents Wilson Kulile Hobongwana and Miriam Ntumpuse Hobongwana. iv ABSTRACT This thesis explores, analyzes and conceptualizes the indigenous knowledge practices concerning health and well-being held by different generations of women and how they are reproduced cross-generationally in a rural isiXhosa-speaking community. It also explores how the relationship between concepts of self, personhood and Ubuntu informs women’s agency. Additionally, this thesis explores how the indigenous knowledge practices might have the potential to augment inclusive and relevant tools for learning for young women, girls and youth. -

Musicians Have the Right to Broadcasting on 88.5 FM on 1 Ence at the Same Time

In The Zone Vol 1 April 2020 Who is Zone Radio? From Cape Town to the World South Africa in Lockdown The Do’s and Don’ts of lockdown Kiss my Chumbawamba So how exactly did bands get their names Whatever happened to... Remembering SA’s bands and artists The Voice of the Valley CONTENTS April 2020 Page 28 Page 22 Welcome To Shorties Blue Bottle Noordhoek Blue Bottle Liquors has been operating successfully since the year 2000. We carry huge ranges of wine, malt whiskies, and are geared for all functions. Our emphasis is on personal service in a safe environment, promoting responsible drinking. We pride ourselves in quality products. We haven’t left it there though!! We have now Kiss my Chumbawamba extended our operation and set up a Traders Association involving several very successful Every great band needs a great name. independent liquor stores who understand their customer’s needs and are extremely aware Page 28 of promoting responsible drinking. They have revamped their stores for a better, secure and informative shopping experience. Being part of the Blue Bottle membership means we offer 20 better prices, professional advice and don’t forget the personal touch of the owner. Features 40 Rainbow cuisine Two Grumpy Old Men 6 We look at some of South Afri- Matt and John are complaining So who is Zone Radio? ca’s traditional dishes. yet again. 24 Zone Radio has quickly estab- 42 lished themselves as “the voice Silver lining 10 essential foods of the valley”. But who exactly Click on the link on the left to Sometimes great things happen What you should be eating this is Zone Radio? as a result of terrible disasters. -

SIM 02 09 01 Nutrition Report 13 Jan 2004

Safety In Mines Research Advisory Committee (SIMRAC) Final Report Nutrition and occupational health and safety in the South African mining industry Part 1 B Dias P Wolmarans JA Laubscher P C Schutte 1 Research Agency : CSIR Miningtek Project number : SIM 02 09 01 Date : December 2003 2 Executive Summary Housing and nutrition have been used as indicators of poverty, and as common targets for intervention to improve public health and reduce health inequalities (Gauldie 1974). The relationship between health, nutrition and housing is well established. The basic human need for shelter and food would appear to make the relationship between poor housing and food, and poor health self evident (Burridge and Omangy, 1993). At the Mine Health and Safety Council meeting in 2001, Mining Occupational Health Advisory Committee (MOHAC) was required to consider the potential impact housing and nutrition has on occupational health and safety in the South African Mining Industry. Historically, miners have been housed and fed in hostels but provisions of both accommodation and nutrition are changing and vary across the industry. There is no recent research to assess whether miners are receiving the proper nutrition and fluid intake for the physical demands of the work they perform in the South African mining industry. Research is therefore needed to assess the nutritional status of mineworkers who live out and those who stay in the hostels and to provide guidelines for a nutritionally adequate diet for mineworkers in various mining environments. The Black labour law was the last law to regulate nutrition in the mines. The regulation was gazetted in 1975 and stipulated the minimum ration scale for “Bantu” employees. -

International Symposium on Sorghum Grain Quality

pji 9- 7 Proceedings of the t5(v-- International Symposium on Sorghum Grain Quality ICRISAT Center Patancheru, India 28-31 October 1981 Sponsored by uSAID Title XII Collaborative Research Suppowt Program on Sorghum and Pearl Millet (INTSORMIL) International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) / Correct citation: ICRISAT (International Crops Research Institute for the Semi- Arid Tropics). 1982. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Sorghum Grain Quality, 28-31 October 1981, Patancheru, A.P., Ind;9. Workshop Coordinators and Scientific Editors L. W. Rooney D. S. Murty Publication Editor J. V. Mertin The International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) is a nonprofit scientific educational institute receiving support from donors through the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research. Donors to ICRISAT include governments and agencies of Australia, Belgium, Canada, Federal Republic of Germany, France, India. Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States, and the following International and private organizations: Asian Development Bank, European Economic Community, Ford Foundation, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, International Development Research Centre, International Fertilizer Development Center, International Fund for Agriculhural Development, the Leverhulme Trust, and the United Nations Developmunt Programme. Responsibility for the information in this publication rests with ICAR, ICRISAT, INTSORMIL, or the individual authors. Where trade names are used this does not constitute endorsement of or discrimination against any product by the Institute. Ii Contents Foreword vii Inaugural Session 1 Welcome Address J. C. Davies 3 Opening Address E.R. Leng 4 Keynote Address-The Importance of Food Quality H. -

Omslag Report V2

The aflatoxin situation in Africa Systematic literature review RIKILT report 2018.010 The aflatoxin situation in Africa Systematic literature review Nathan Meijer 1, Gijs Kleter 1, Rosa Amalia Safitri 1, Monique de Nijs 1, Marie-Luise Rau 2, Ria Derkx 3, Joke Webbink 3, Marijn Post 3, Yuca Waarts 2, Ine van der Fels-Klerx 1 1 RIKILT Wageningen University & Research 2 Wageningen Economic Research 3 Wageningen University & Research - Library This research has been carried out by Wageningen University & Research and financed by Partnership for Aflatoxin Control in Africa (PACA) through funds made available to PACA by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Mars, Incorporated (project number 1277360301). PACA acknowledges the contribution of the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) in producing this report which is a follow up to the CTA/PACA 2016 Working Paper “Improving the evidence base on aflatoxin contamination and exposure in Africa” written by Sheila Okoth. Wageningen, December 2018 RIKILT report 2018.010 RIKILT report 2018.010 | 1 Project number: 1277360301 Project title: The aflatoxin situation in Africa Project leader: Nathan Meijer © 2018 African Union Commission / PACA. This study was financed by Partnership for Aflatoxin Control in Africa (PACA) through funds made available to PACA by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Mars, Incorporated. PACA acknowledges the contribution of the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) in producing this report which is a follow up to the CTA/PACA 2016 Working Paper “Improving the evidence base on aflatoxin contamination and exposure in Africa” written by Sheila Okoth. This report is published by RIKILT Wageningen University & Research, institute within the legal entity Wageningen Research Foundation with the copyright holder’s permission. -

South Africa - Republic Of

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 11/27/2013 GAIN Report Number: South Africa - Republic of Post: Pretoria Food Processing Ingredients Food Processing Ingredients Market Report Approved By: Nicolas Rubio Prepared By: Margaret Ntloedibe Report Highlights: The report remains the same as the 2012 Food Processing Ingredients report; only the 2013 statistics were updated. Executive Summary: South Africa’s agro-food and beverages processing sector, serving a population of about 53 million, remains a significant component of the manufacturing economy. The sector is developed, highly concentrated and competitive, producing high quality and niche products for local and international markets. The agro-processing (food and beverages) industry contributed $2,903 million between January-August 2013, an annual percentage change of 4 percent. The sector has a number of competitive advantages, making it an important trading partner. The establishment of preferential trade agreements such as Customs Union for Southern African Customs Union countries, African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) for the U.S. market, a Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with Southern African Development Community (SADC) and with the European Union (EU), and other agreements which confer generous benefits to South Africa. South Africa largest exports products are grapes, wine, apples, pears, citrus, and food preparations. Other important export products are avocados, pineapples, dates, and preserved fruits and nuts. South Africa January-August 2013 exports of agricultural, fish and forestry products to the United States experienced a 5 percent increase to $207 million as a result of export of edible fruit & nuts, and beverage spirits & vinegar. -

Better Things

BETTER THINGS by Jeanette Malherbe Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA Creative Writing in the School of Language and Literature Studies, University of the Witwatersrand. November 2011 1 Contents Page A Red-letter Day 3 Face to Face 9 Good Eating 14 The Hooks in Jazz 19 The Good Life 27 Seamstresses of Malimode 33 Psalmen en Gezangen 41 A Life Shared 48 Heart’s Blood 54 Uma Casa Portuguesa 61 Ukuhlalisa Umsamo 69 Chief of the Monkeys 78 Tea and Coffee 83 The Paid Piper 88 A Good Day for Loki 95 Running the Gauntlet 102 The Immaculate Character 109 Ash 116 Torn Apart 125 Spiritual Supremacy 138 Homesick 148 Gifts of Fortune 154 2 A Red-letter Day A longhair lilac-point Himalayan walks along the paving under the acacia trees, high-stepping over the mud washed down by the sprinklers and avoiding the thorns. Her coat lifts in the breeze, her tail waves behind her. Anna Purrna of Khorasan has been visiting the shrubbery that lines the driveway. For the rest, this place is paved over and bricked up. Houses front the other side of the road, each in a different style but all equally huge, with only a token garden before each one: four standard roses here, a row of squared-off golden privets there. From somewhere above the cat, a loerie’s creaking call sounds; she looks up, locates the bird on a high branch and sits down to consider it. Her long fur has picked up mud, leaves, twigs. -

African Sorghum-Based Fermented Foods: Past, Current and Future Prospects

nutrients Review African Sorghum-Based Fermented Foods: Past, Current and Future Prospects Oluwafemi Ayodeji Adebo Department of Biotechnology and Food Technology, Faculty of Science, University of Johannesburg (Doornfontein Campus), P.O. Box 17011 Johannesburg, Gauteng 2028, South Africa; [email protected]; Tel.: +27-11-559-6261 Received: 28 February 2020; Accepted: 14 April 2020; Published: 16 April 2020 Abstract: Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) is a well-known drought and climate resistant crop with vast food use for the inhabitants of Africa and other developing countries. The importance of this crop is well reflected in its embedded benefits and use as a staple food, with fermentation playing a significant role in transforming this crop into an edible form. Although the majority of these fermented food products evolve from ethnic groups and rural communities, industrialization and the application of improved food processing techniques have led to the commercial success and viability of derived products. While some of these sorghum-based fermented food products still continue to bask in this success, much more still needs to be done to further explore evolving techniques, technologies and processes. The addition of other affordable nutrient sources in sorghum-based fermented foods is equally important, as this will effectively augment the intake of a nutritionally balanced product. Keywords: sorghum; fermentation; lactic acid bacteria; fermented products; food security; 4th industrial revolution (4IR) 1. Introduction In terms of production quantity, sorghum is the fifth most important cereal crop in the world after rice, wheat, maize and barley, and the most grown cereal in Sub-Saharan Africa, after maize [1–3].