European History Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Daskalov R Tchavdar M Ed En

Entangled Histories of the Balkans Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović, University College London Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos, Columbia University Alex Drace-Francis, University of Amsterdam Jasna Dragović-Soso, Goldsmiths, University of London Christian Voss, Humboldt University, Berlin Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic, University of Munich Lenard J. Cohen, Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup, Columbia University Robert M. Hayden, University of Pittsburgh Robert Hodel, Hamburg University Anna Krasteva, New Bulgarian University Galin Tihanov, Queen Mary, University of London Maria Todorova, University of Illinois Andrew Wachtel, Northwestern University VOLUME 9 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Entangled Histories of the Balkans Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover Illustration: Top left: Krste Misirkov (1874–1926), philologist and publicist, founder of Macedo- nian national ideology and the Macedonian standard language. Photographer unknown. Top right: Rigas Feraios (1757–1798), Greek political thinker and revolutionary, ideologist of the Greek Enlightenment. Portrait by Andreas Kriezis (1816–1880), Benaki Museum, Athens. Bottom left: Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864), philologist, ethnographer and linguist, reformer of the Serbian language and founder of Serbo-Croatian. 1865, lithography by Josef Kriehuber. Bottom right: Şemseddin Sami Frashëri (1850–1904), Albanian writer and scholar, ideologist of Albanian and of modern Turkish nationalism, with his wife Emine. Photo around 1900, photo- grapher unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Entangled histories of the Balkans / edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. pages cm — (Balkan studies library ; Volume 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

The Eusebius Lab International Working Papers Series

Series Εργαστήριο Ιστορίας, Πολιτικής, Διπλωματίας και Γεωγραφίας της Εκκλησίας Laboratory of History, Policy, Diplomacy and Geography of the Church Papers The Eusebius Lab International Working Papers Series Eusebius Lab International Working Paper 2020/07 Working The Greek Orthodox Church during the Dictatorship of the Colonels Relations of Church and State in Greece at the seven - year period of military Junta (1967-1974) International Lab Charalampos Μ. Andreopoulos School of Pastoral and Social Theology Eusebius Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Campus GR 54636 Thessaloniki, GREECE http://eusebiuslab.past.auth.gr The ISSN:2585-366X The Greek Orthodox Church during the Dictatorship of the Colonels Relations of Church and State in Greece at the seven - year period of military Junta (1967-1974) Charalampos Μ. Andreopoulos Dr. of Theology AUTH Περίληψη Τό ἐκκλησιαστικό ἦταν τό μοναδικό ἀπό τά θέματα τῆς ζωῆς τοῦ τόπου ὅπου ἡ δικτατορία τῶν Συνταγματαρχῶν εἰς ἀμφότερες τίς φάσεις αὐτῆς (ἐπί Γ. Παπαδοπούλου, 1967-1973 καί ἐπί Δημ. Ἰωαννίδη, 1973-1974) ἐφήρμοσε διαφοροποιημένη πολιτική. Καί στίς δυό περιπτώσεις ὑπῆρχε ἴδια τακτική: Παρέμβαση στά ἐσωτερικά της Ἐκκλησίας τῆς Ἑλλάδος, παραβίαση τῆς κανονικῆς τάξεως (= τῶν ἐκκλησιαστικῶν κανόνων), ἐπιβολή Ἀρχιεπισκόπου τῆς ἐμπιστοσύνης τοῦ κατά περίπτωση πραξικοπηματία (Γ. Παπαδοπούλου-Δ. Ἰωαννίδη), πλαισιωμένου ἀπό δια- φορετική καί παντοδύναμη κάθε φορά ὁμάδα ἀρχιερέων. Κατά τήν πρώτη φάση τῆς δικτατορί- ας ὁ κανονικός καί νόμιμος Ἀρχιεπίσκοπος Χρυσόστομος Β΄ (Χατζησταύρου) ἀρνούμενος -

Welcome to Ioannina a Multicultural City…

Welcome to Ioannina The city of Giannina, attraction of thousands of tourists every year from Greece and around the world, awaits the visitor to accommodate him with the Epirus known way, suggesting him to live a unique combination of rich past and impressive present. Built next to the legendary lake Pamvotis at 470 meters altitude, in the northwest of Greece, it is the biggest city of Epirus and one of the most populous in the country. History walks beside you through the places, the impressive landscape that combines mountain and water, museums with unique exhibits and monuments also waiting to lead you from the Antiquity to the Middle Byzantine and Late Byzantine period, the Turks, Modern History. And then ... the modern city with modern structures (University, Hospital, Airport, Modern Highway - Egnatia - Regional, local and long distance transportation, Spiritual and Cultural Centres) offer a variety of events throughout the year. Traditional and modern market, various entertainment options, dining and accommodation. A multicultural city… Ioannina arise multiculturally and multifacetedly not only through narrations. Churches with remarkable architecture, mosques and a synagogue, the largest in Greece, testify the multicultural character of the city. The coexistence of Christians, Muslims and Jews was established during the administration of Ali Pasha. The population exchange after the Minor Asia destruction and annihilation of most Jews by the Germans changed the proportions of the population. Muslims may not exist today and the Jews may be few, only those who survived the concentration camps, but the city did not throw off this part of the identity. Today, there are four mosques, three of them very well preserved, while the Jewish synagogue, built in 1826, continues to exist and be the largest and most beautiful of the surviving religious buildings of the Greek Jews. -

The Revival of Political Hesychasm in Greek Orthodox Thought: a Study of the Hesychast Basis of the Thought of John S

ABSTRACT The Revival of Political Hesychasm in Greek Orthodox Thought: A Study of the Hesychast Basis of the Thought of John S. Romanides and Christos Yannaras Daniel Paul Payne, B.A., M.Div. Mentor: Derek H. Davis, Ph.D. In the 1940s Russian émigré theologians rediscovered the ascetic-theology of St. Gregory Palamas. Palamas’s theology became the basis for an articulation of an Orthodox theological identity apart from Roman Catholic and Protestant influences. In particular the “Neo-Patristic Synthesis” of Fr. Georges Florovsky and the appropriation of Palamas’s theology by Vladimir Lossky set the course for future Orthodox theology in the twentieth century. Their thought had a direct influence upon the thought of Greek theologians John S. Romanides and Christos Yannaras in the late twentieth century. Each of these theologians formulated a political theology using the ascetic-theology of Palamas combined with the Roman identity of the Greek Orthodox people. Both of these thinkers called for a return to the ecclesial-communal life of the late Byzantine period as an alternative to the secular vision of the modern West. The resulting paradigm developed by their thought has led to the formation of what has been called the “Neo- Orthodox Movement.” Essentially, what the intellectual and populist thinkers of the movement have expressed in their writings is “political hesychasm.” Romanides and Yannaras desire to establish an Orthodox identity that separates the Roman aspect from the Hellenic element of Greek identity. The Roman identity of the Greek people is the Orthodox Christian element removed from the pagan Hellenism, which, as they argue, the Western powers imposed on the Greek people in the establishment of the modern nation-state of Greece in 1821. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Archaeology in the community - educational aspects: Greece: a case-study Papagiannopoulos, Konstantinos How to cite: Papagiannopoulos, Konstantinos (2002) Archaeology in the community - educational aspects: Greece: a case-study, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4630/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Konstantinos Papagiannopoulos Archaeology in the community - educational aspects. Greece: a case-study (Abstract) Heritage education in Greece reproduces and reassures the individual, social and national sel£ My purpose is to discuss the reasons for this situation and, by giving account of the recent developments in Western Europe and the new Greek initiatives, to improve the study of the past using non-traditional school education. In particular, Local History projects through the Environmental Education optional lessons allow students to approach the past in a more natural way, that is through the study of the sources and first hand material. -

KATOVICES” E BE-Së Humor Politik

LEKË 30 VITI III - NR. 291 - E DIEL - 08-12-2013 “RILINDASI” ɽ FAQE 17-24 STUDENTI I DHJETORIT DIPLOMACIA ɽ Faqe 5 At Zef Pllumi për reformat Ja ngjarjet e vitit 1990. Si u spostuan Kuriozitete mbi veprimtarët kryesorë. Azem Hajdari himnet “alternative” të shtetit shqiptarp shërbente më shumë Martir, se Pishtar MYFTAR GJANA: Shtyhet mandati i ambasadorit MARRËVESHJAARRËVESHJA ɽ FAQE 8 , BERISHA AGJENT Arvizu, s’takon Shqipëriahqipëria përpë herë të parë Berishën me Europolin I “KATOVICES” e BE-së Humor politik APELI ɽ FAQE 15 NGA ARBEN DUKA E sëmura 3 vjeç me SIDA, gjyshja kërkon Ç’iaÇ thoshte ndihmë shtetit bilbili..b (Pjesa(Pj e tretë) ɽ FAQE 7 LEGALIZIMI Ç’poÇ ia thotë bilbili, Rama: zogzo me zë të butë, vajtiv puna jonë, ALUIZNI, hiqh e mos këput!... praktikisht ɽ Vijon në faqen 14 në gjendje bashkë me rubrikën “VIP-a dhe Rripa” falimenti KomentK NGA NIKOLLA SUDAR*) “Olldashi nuk duhej ta ShijakuS dhe KORÇË ɽ FAQE 9 pranonte garën në PD” problematikap Arrestohen akutea e tij bankierët, Lulzim Basha? Një ”yll” që do milionamiliona vjetvjet të shkëlqejë.shkëlqejë. hijaku, ky qytet i vogël por vodhën 2.8 Ka ardhur koha për arrestime VIP-ash për korrupsion me histori të madhe (mjafton Stë kujtojmë thënien-lapidar milionë euro ɽ NE FAQE 2-3 të kreshnikut të maleve Bajram Curri:... ɽ vijon në faqen 12 NDËRTIMET PA LEJE ɽ FAQE 6 Pallati i Bashës bosh, Tahiri në Vlorë Gati “goditja” tjetër nga bashkia në hyrje të Durrësit Cyan magenta yellow black 2 Politikë E shtunë, 7 dhjetor 2013 DREJTUESI Studentor jep detaje për lindjen DHJETORI ‘90 e pluralizmit, “të dërguarit’ me pardesy të bardha që shpallën komisionin nismëtar të PD: Dhe ish-gjimnazistët, tani bëjnë si dhjetoristë Gjana: “Katovica” e Alia bënë Berishën kreun e PD “Meksi prishi skemën e të dërguarve të Ramiz Alisë” JAKIN MARENA grup studentësh mes të cilëve Kujtim TIRANE Allaraj, Dritan Çuni, Hajredin Muja kemi shkuar me nxitim atje dhe jemi NË FOTO: përfshirë në protestat e studentëve, Azem Hajdari, ë një intervistë për ku kemi takuar studentët më aktivë që Sali Berisha gazetën “Shqiptarja. -

Modern Greek Translations (1686-1818) of Latin Historical Works Traducciones Griegas Modernas (1686-1818) De Obras Históricas Latinas

Studia Philologica Valentina Vol. 17, n.s. 14 (2015) 257-272 ISSN: 1135-9560 Modern Greek Translations (1686-1818) of Latin Historical Works Traducciones griegas modernas (1686-1818) de obras históricas latinas Vasileios Pappas University of Cyprus Data de recepció: 13/02/2015 Data d’acceptació: 03/06/2015 1. Introduction Even before the Fall of Constantinople (1453), many Latin works have been translated in Greek and Modern Greek language.1 This translative tradition continues in the post-Byzantine era; many scholars with deep knowledge of Latin language and literature are engaged in writing in Latin as well as in translating Latin texts.2 In this paper we will focus our attention especially in translations of Latin historiography. The presentation will be brief; it includes the report of the titles of these works and the attempt to answer – through the authors themselves’s words – to this question: for what reason they treated specifically with translations of Latin historical works? 1 D. Nikitas, «Traduzioni greche di opera latine», in S. Settis (ed.) I Greci. Storia Cultura Arte Società 3, I Greci oltre la Grecia, Turin, 2001, pp. 1035-51. 2 These works exist in the website of anemi (<http://anemi.lib.uoc.gr/?lang=el>). The pages of the passages are given in footnotes. The pages which are without enu- meration are included into parenthesis. For the post-byzantine Latinitas of Greek scholars, see Δ. Νικήτας, «Μεταβυζαντινή Latinitas: Δεδομένα και ζητούμενα», ΕΕΦΣ ΑΠΘ, (Τμήμα Φιλολογίας) 10 (2002-2003), pp. 34-46. For the translations of 18th century of foreign works in Modern Greek, see Γ. -

Hellenism and the Making of Modern Greece: Time, Language, Space

8. Hellenism and the Making of Modern Greece: Time, Language, Space Antonis Liakos Ξύπνησα με το μαρμάρινο τούτο κεφάλι στα χέρια που μου εξαντλεί τους αγκώνες και δεν ξέρω που να τ᾿ακουμπήσω. Έπεφτε στο όνειρο καθώς έβγαινα από το όνειρο έτσι ενώθηκε η ζωή μας και θα είναι δυσκολο να ξαναχωρίσει. I awoke with this marble head in my hands it exhausts my elbows and I do not know where to put it down. It was falling into the dream as I was coming out of the dream. So our life became one and it will be very difficult for it to separate again. George Seferis, Mythistórima 1. Modern Greek History 1.1. The Construction of National Time Just as the writing of modern history developed within the context of national historiography since the nineteenth century, so the concept of “nation” has become one of the essential categories through which the imagination of space and the notion of time are constructed.1 This is the tradition and the institutional environment within which contemporary historians conduct their research and write their texts, reconstructing and reinforcing the structures of power that they experience. Historically, the concept of the nation has been approached from two basically different perspectives, despite internal variations. The first is that of the nation builders and the advocates of nationalism. Despite the huge differences among the multifarious cases of nation formation, a common denominatorCopyright can be recognized: the nation Material exists and the issue is how it is to be represented in the modern world. But representation means performance, and through it the nation learns how to conceive itself and 1 Sheeham 1981. -

Stvdia Philologica Valentina

STVDIA PHILOLOGICA VALENTINA Número 17, n.s. 14 Any 2015 Via ad sapientiam: latín, griego y transmisión del conocimiento DEPARTAMENT DE FILOLOGIA CLÀSSICA UNIVERSITAT DE VALÈNCIA STVDIA PHILOLOGICA VALENTINA Departament de Filologia Clàssica - Universitat de València CONSELL DE REDACCIÓ Director: Jaime Siles Ruiz (Universitat de València) Secretari: Josep Lluís Teodoro Peris (Universitat de València) Vocals: Carmen Bernal Lavesa (Universitat de València), Marco A. Coronel Ramos (Universitat de València), Maria Luisa del Barrio Vega (Universidad Conplutense de Madrid), Jorge Fernández López (Universidad de la Rioja), Concepción Ferragut Domínguez (Universitat de València), Carmen González Vázquez (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid), Ferran Grau Codina (Universitat de València), Mikel Labiano Ilundain (Universitat de València), Mari Paz López Martínez (Universitat d’Alacant), Mercedes López Salvà (Universidad Complutensa de Madrid), Antonio Melero Bellido (Universitat de València), Matteo Pellegrino (Università degli Studi di Foggia), Violeta Pérez Custodio (Universidad de Cádiz), Elena Redondo Moyano (Universidad del País Vasco), Lucía Rodríguez-Noriega Guillen (Universidad de Oviedo), Juana María Torres Prieto (Universidad de Cantabria) Coordinadors del volum: Concepción Ferragut Domínguez (Universitat de València) y María Teresa Santamaría Hernández (Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha) CONSELL ASSESSOR Trinidad Arcos Pereira Marc Mayer Olivé Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria Universitat de Barcelona † Máximo Brioso Sánchez † Carles -

Rrenjet Prill 2014.Indd

Anno 12 Distribuzione gratuita in: Mensile di attualità e cultura italo-albanese Albania, Australia, Numero 1 Belgio, Canada, Germania, Direttore editoriale: Hasan Aliaj Grecia, Francia, Italia, Aprile 2014 Stati Uniti e Svizera L’Albania dipinta e HHylli,ylli, mbretimbreti i parëparë i ilirëveilirëve dhedhe raccontata da Mary Adelaide Walker (1820-1905) mmisteriisteri i kafkëskafkës sësë kristaltëkristaltë L’Albania ha sempre esercitato un gran- de fascino sulle donne: fin dai secoli Nga ALBERT HITOALIAJ është thërrmuar!” Por nuk ka rëndësi se scorsi, quando l’interesse per le antiche sa e çuditshme dhe e pabesueshme mund culture mediterranee cominciò a porta- ë maj të vitit 2008, Harrison Ford e të duket ajo kafkë. Kushdo mund ta shohë re in giro per l’Europa scrittori, artisti gjeti veten përsëri në xhirimet e një atë të ekspozuar në Muzeun e Indianëve të e intellettuali di ogni paese, i Balcani in Nprej roleve më klasikë të aventurës, Amerikës. Kërkuesit panë se kristali ishte generale e l’Albania in particolare sono Indiana Jones. Drejtuesi i këtij filmi ishte i gdhendur kundër aksit natyral të kristalit. stati fra le mete preferite da donne in famshmi Steven Spielberg dhe në qendër Skulptorët modernë të kristalit, gjithmonë viaggio di piacere o di ricerca o, per me- të aksionit ishte beteja që zhvillohej për kujdesen që të dinë sesi është aksi ose glio dire, che viaggiavano per il piacere zotërimin e një kafke të kristaltë, e cila simetria e orientimit molekular të kristalit, della ricerca. kishte fuqi të mbinatyrshme. Filmi, duke pasi nëse ata do të gdhendnin në drejtim të qenë se trajtonte edhe një prej çështjeve kundërt me këtë aks, atëherë kristali do të Page 8 më misterioze reale ekzistuese, atë të thyhej, madje edhe nëse do të përdornin kafkave të kristalta, për vitin që shkoi u lazer apo teknika të tjera të avancuara rendit në vend të dytë në radhën e fitimeve për gdhendje. -

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique Vol. 8, 2011 Establishing the Discipline of Classical Philology in Nineteenth-century Greece Matthaiou Sophia Institute for Neohellenic Research/ NHRF http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/hr.279 Copyright © 2011 To cite this article: Matthaiou, S. (2012). Establishing the Discipline of Classical Philology in Nineteenth-century Greece. The Historical Review/La Revue Historique, 8, 117-148. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/hr.279 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 12/12/2018 10:14:06 | ESTABLISHING THE DISCIPLINE OF CLASSICAL PHILOLOGY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY GREECE Sophia Matthaiou Abstract: This paper outlines the process of establishing the discipline of classical philology in Greece in the nineteenth century. During the period shortly before the Greek War of Independence, beyond the unique philological expertise of Adamantios Korais, there is additional evidence of the existence of a fledging academic discussion among younger scholars. A younger generation of scholars engaged in new methodological quests in the context of the German school of Alterthumswissenschaft. The urgent priorities of the new state and the fluidity of scholarly fields, as well as the close association of Greek philology with ideology, were some of the factors that determined the “Greek” study of antiquity during the first decades of the Greek state. The rise of classical philology as an organized discipline during the nineteenth century in Greece constitutes a process closely associated with the conditions under which the new state was constructed. This paper will touch upon the conditions created for the development of the discipline shortly before the Greek War of Independence, as well as on the factors that determined its course during the first decades of the Greek State.1 Although how to precisely define classical philology as an organized discipline is subject to debate, our basic frame of reference will be the period’s most advanced “school of philology”, the German school. -

Newsletter 2014-2015

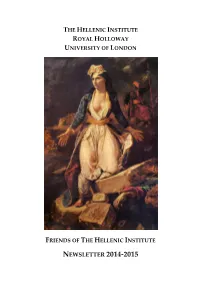

THE HELLENIC INSTITUTE ROYAL HOLLOWAY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON FRIENDS OF THE HELLENIC INSTITUTE NEWSLETTER 2014-2015 FRONTISPIECE: La Grèce sur les ruines de Missolonghi by Eugène Delacroix (1826). Oil on canvas, 208×147cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, France. Reproduced from http://www.lacma.org/art/exhibition/delacroixs-greece- ruins-missolonghi © The Hellenic Institute, Royal Holloway, University of London International Building, Room 237, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK Tel: +44 (0) 1784 443791/443086, fax: +44 (0) 1784 433032 E-mail: [email protected] and [email protected] Web site: http://www.rhul.ac.uk/hellenic-institute/ TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Director 4 About The Hellenic Institute 9 The Hellenic Institute News 10 Student News 10 Studentships, bursaries and prizes awarded to students (2013-2015) 12 Grants awarded to students by the College and other institutions (2013-2015) 13 Grants and donations to the Institute 13 Appointment of Lecturer in Modern Greek History 14 Visiting Scholars 16 Events (April 2013-present) 16 Forthcoming Events 39 The Hellenic Institute Studentships, Bursaries and Prizes (2015/16) 40 Courses in Modern Greek Language and Culture (2015/16) 42 Major Research Projects 44 News of members, associated staff, former students and visiting scholars 49 Recent and forthcoming publications by members, associated staff, 70 former students and visiting scholars Five-Year Plan (2015-2020) 96 Obituary of Chrysoula Nandris (née Alvanou) 97 Letter from Mr Edward Young, Deputy Private Secretary to 100 H.M. The Queen The Hellenic Institute Steering Group, Associated Staff and Visiting 101 Scholars Friends of The Hellenic Institute Membership and Donation Form 103 Gift Aid Declaration 104 4 FRIENDS OF THE HELLENIC INSTITUTE Letter from the Director 8th June 2015 Dear Friend, Since my last communication there have been exciting developments at The Hellenic Institute.