The Story of the Malakand Field Force, by Sir Winston S. Churchill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Db List for 04-02-2020(Tuesday)

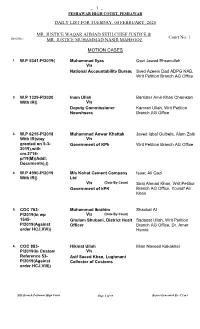

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE MUHAMMAD NASIR MAHFOOZ MOTION CASES 1. W.P 5341-P/2019() Muhammad Ilyas Qazi Jawad Ehsanullah V/s National Accountability Bureau Syed Azeem Dad ADPG NAB, Writ Petition Branch AG Office 2. W.P 1329-P/2020 Inam Ullah Barrister Amir Khan Chamkani With IR() V/s Deputy Commissioner Kamran Ullah, Writ Petition Nowshsera Branch AG Office 3. W.P 6215-P/2018 Muhammad Anwar Khattak Javed Iqbal Gulbela, Alam Zaib With IR(stay V/s granted on 5-3- Government of KPk Writ Petition Branch AG Office 2019),with cm.2715- p/19(M)(Addl: Documents),() 4. W.P 4990-P/2019 M/s Kohat Cement Company Isaac Ali Qazi With IR() Ltd V/s (Date By Court) Siraj Ahmad Khan, Writ Petition Government of kPK Branch AG Office, Yousaf Ali Khan 5. COC 763- Muhammad Ibrahim Shaukat Ali P/2019(in wp V/s (Date By Court) 1545- Ghulam Shubani, District Health Sadaqat Ullah, Writ Petition P/2019(Against Officer Branch AG Office, Dr. Amer order HCJ,XVI)) Hamid 6. COC 883- Hikmat Ullah Mian Naveed Kakakhel P/2019(in Custom V/s Reference 53- Asif Saeed Khan, Lughmani P/2019(Against Collector of Customs order HCJ,VIII)) MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 88 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. -

Accession of the States Had Been the Big Issue After the Division of Subcontinent Into Two Major Countries

Journal of Historical Studies Vol. II, No.I (January-June 2016) An Historical Overview of the Accession of Princely States Attiya Khanam The Women University, Multan Abstract The paper presents the historical overview of the accession of princely states. The British ruled India with two administrative systems, the princely states and British provinces. The states were ruled by native rulers who had entered into treaty with the British government. With the fall of Paramountacy, the states had to confirm their accession to one Constituent Assembly or the other. The paper discusses the position of states at the time of independence and unfolds the British, congress and Muslim league policies towards the accession of princely states. It further discloses the evil plans and scheming of British to save the congress interests as it considered the proposal of the cabinet Mission 1946 as ‘balkanisation of India’. Congress was deadly against the proposal of allowing states to opt for independence following the lapse of paramountancy. Congress adopted very aggressive policy and threatened the states for accession. Muslim league did not interfere with the internal affair of any sate and remained neutral. It respected the right of the states to decide their own future by their own choice. The paper documents the policies of these main parties and unveils the hidden motives of main actors. It also provides the historical and political details of those states acceded to Pakistan. 84 Attiya Khanam Key Words: Transfer of Power 1947, Accession of State to Pakistan, Partition of India, Princely States Introduction Accession of the states had been the big issue after the division of subcontinent into two major countries. -

Auditor General of Pakistan

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS DISTRICT DIR LOWER AUDIT YEAR 2018-19 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ............................................................... i Preface ................................................................................................................. iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................. iv SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ................................................................... viii I: Audit Work Statistics ...................................................................................... viii II: Audit observations Classified by Categories .................................................. viii III: Outcome Statistics ......................................................................................... ix IV: Table of Irregularities pointed out ................................................................... x V: Cost Benefit Ratio ............................................................................................ x CHAPTER-1 ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Local Governments Dir Lower .................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) ........................... 5 1.1.3 Comments on -

Principles of Modern American Counterinsurgency: Evolution And

Terrain, Tribes, and Terrorists: Pakistan, 2006-20081 By David J. Kilcullen, Partner, The Crumpton Group LLC Brookings Counterinsurgency and Pakistan Paper Series. No. 3. “The two main factors for you will be the terrain and the tribes. You have to know their game and learn to play it, which means you first have to understand their environment,” Professor Akbar Ahmed told me in May 2006. In the field, with military and civilian teams and local people in locations across Afghanistan and Pakistan at various times through the next three years, the wisdom of Professor Ahmed’s insight came home to me again and again. The fact is that the terrain and the tribes drive ninety percent of what happens on the Frontier, while the third factor, which accounts for the other ten percent, is the presence of transnational terrorists and our reaction to them. But things seem very different in Washington or London from how they seem in Peshawar, let alone in Bajaur, Khyber or Waziristan—in that great tangle of dust-colored ridges known as the Safed Koh, or “white mountains”. This is a southern limb of the Hindu Kush, the vast range that separates Afghanistan (which lies on the immense Iranian Plateau that stretches all the way to the Arabian Gulf) from the valley of the Indus, the northern geographical limit of the Indian subcontinent. The young Winston Churchill, campaigning here in 1897, wrote that “all along the Afghan border every man’s house is his castle. The villages are the fortifications, the fortifications are the villages. Every house is loopholed, and whether it has a tower or not depends only on its owner’s wealth.”2 “All the world was going ghaza” Churchill was describing the operations of the Malakand Field Force around the village of Damadola, in Bajaur Agency, during the Great Frontier War of 1897— a tribal uprising inspired and exploited by religious leaders who co-opted local tribes’ opposition to the encroachment of government authority (an alien and infidel presence) into their region. -

Db List for 25.02.2020(Tuesday)

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 25 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE MUHAMMAD NASIR MAHFOOZ MOTION CASES 1. W.P 1687- Haseeb ur Rehman Muhammad Saeed Khan P/2020(Detenue V/s Akbar Ali) Government of KPK Deputy Attorney General, Kamran Ullah, Izhar ul Hussain, Shahzad Anjum, Mirza Khalid Mahmood., Writ Petition Branch AG Office, Salman Khan 5259 (Focal Person IGP) 2. COC 79-P/2020(in Kifayat ullah Bashir Khan Wazir wp 4426- V/s P/2018(Against Hayam Hassan Writ Petition Branch AG Office order HCJ,XVI)) 3. COC 83-P/2020(in Imran Khan Jawad khan wp 49- V/s P/2018(Against Khayam Hassan Khan, Writ Petition Branch AG Office order HJ-III,V)) Chairman Workers Welfare Board 4. COC 84-P/2020(in Amirullah Khan Bashir Khan Wazir wp 819- V/s B/2016(Against Hayam Hassan, Secretary Writ Petition Branch AG Office order HCJ,VII)) Labour/ Chairm Workers Wel 5. COC 101- Junaid Ahmad Muhammad Ibrar Khan Afridi P/2020(in wp V/s 5991- Tahir Nadeem, Director General Sadaqat Ullah, Writ Petition P/2018(Against Health Services Branch AG Office, Dr. Amer order HJ- Hamid Exjudge,VIII)) Note: This case will be heard via video link at 10:00 am. 6. Cr.A 1406- Amir Abdullah Malik Immad Azam (Kohat) P/2019(model V/s (Date By Court) court (criminal)) The State Cr Appeal Branch AG Office MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 104 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 25 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. -

Resetting Pakistan's Relations with Afghanistan

Resetting Pakistan’s Relations with Afghanistan Asia Report N°262 | 28 October 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Policy Imperatives and Internal Implications ................................................................. 2 A. Pakistan’s Monroe Doctrine and Pashtun proxies .................................................... 2 B. Interventionist Ambitions and Domestic Implications ............................................. 5 C. Civil-Military Relations and Afghan Policy ............................................................... 8 III. Expanding Economic Ties ................................................................................................ 11 A. Opportunities ............................................................................................................. 11 B. Constraints ................................................................................................................. 12 IV. Afghans in Pakistan .......................................................................................................... 18 A. The Refugee Question ............................................................................................... -

PRELIMINARY DAMAGE and NEEDS ASSESSMENT Immediate Restoration and Medium Term Reconstruction in Crisis Affected Areas

Pakistan North West Frontier Province and Federally Administered Tribal Areas Public Disclosure Authorized PRELIMINARY DAMAGE AND NEEDS ASSESSMENT Immediate Restoration and Medium Term Reconstruction in Crisis Affected Areas Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared By Asian Development Bank and World Bank for Government of Pakistan Public Disclosure Authorized Islamabad, Pakistan November 2009 CURRENCY AND EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit = Pakistan Rupee US$1 = PKR 80 FISCAL YEAR July 1 - June 30 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank AHQ Agency Headquarter AI Artificial Insemination ATM Automatic Teller Machine BHU Basic Health Unit C&W Communication and Works CERINA Conflict Early Recovery Initial Needs Assessment CH Civil Hospital CNIC Computerized National Identity Card CSR Composite Schedule of Rates DCO District Coordination Officer DFID Department for International Development DHQ District Headquarter DISCO Distribution Company DoE Department of Education DNA Damage and Needs Assessment EIAMF Environmental Impact Assessment and Management Framework FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FCR Frontier Crimes Regulation FDMA FATA Disaster Management Authority FHA Frontier Highway Authority FLCF First Level Care Facility GDP Gross Domestic Product GoNWFP Government of North West Frontier Province GoP Government of Pakistan HC High Court HH Household HIES Household Integrated Economic Survey HT High Tension IDP Internally Displaced Persons IED Improvised Explosive -

Special Issue

II/2015 NAGAARA SPECIAL ISSUE Sikh Warriors in the Great War The Third Annual Conference on the Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, jointly hosted by the Chardi Kalaa Foundation and the San Jose Gurdwara, took place on 13 September 2014 at San Jose in California, USA. One of the largest and arguably most beautiful gurdwaras in North America, the Gurdwara Sahib at San Jose was founded in San Jose, California, USA in 1985 by members of the then-rapidly growing Sikh community in the Santa Clara Valley EEditorialEditorial Sikh Warriors in the Great War he ferocious battles during the Anglo-Sikh First Indian combat troops of the 3rd (Lahore) Wars of 1845-46 and 1848-49 defined for Division sailed from Karachi and Bombay westwards, T all time, if indeed this was ever necessary, these being vanguard of the million more who the indomitable fighting prowess and spirit of the were to follow. Instead of Egypt, however, the Sikh warrior. During the ensuing occupation of Indian Expeditionary Force were diverted to France the Punjab by the expanding colonists, the Khalsa where the British Expeditionary Force (the "Old soldiery was sought to be disbanded and indeed the Contemptibles") were shattered and exhausted after process had begun when the British administration two months of bitter fighting against the German were confronted by the stark reality of policing and Army's overwhelming numbers. The situation was defending the turbulent northwest frontier region perilous and but for the Indian Army, the German with Afghanistan. Kaiser’s grand plan to smash the French and British armies, secure the Channel ports and declare victory Thus, without much ado but certainly some by Christmas 1914, would well have been realised. -

Distribution of Mesopotamia Expeditionary Corps, 18 November 1917

Distribution of Mesopotamia Expeditionary Corps 18 November 1917 TIGRIS FRONT (General HQ in Baghdad) Cavarly Division: (HQ at Sadiya, Tigris right bank) 6th Cavalry Brigade: 14th Hussars 21st Cavalry 22nd Cavalry 15th Machine Gun Squadron No. 2 Field Troop, 2nd Sappers & Miners 6th Cavalry Brigade Supply & Transport Company 7th Cavalry Brigade: 13th Hussars 13th Lancers 14th Lancers 16th Machine Gun Squadron 7th Cavalry Brigade Field Troop,RE 7th Cavalry Brigade Supply & Transport Company Division Troops: HQ, Divisional Artillery "S" Battery RHA (6 guns) "V" Battery, RHA (6 guns) Cavalry Divisional Signal Squadron 1st ANZAC Wireless Signal Squadron (3 pack stations) Cavalry Divisional Troops Supply and Transport Company No. 119 Combined Cavalry Field Ambulance No. 131 Indian Combined Cavalry Field Ambulance No. 30 Sanitary Section No. 4 Mobile Veterinary Section No. 5 Mobile Veterinary Section 11th Cavalry Brigade: (forming) 7th Hussars (not yet arrived from India) 23rd Cavalry Guides Cavalry 25th Machine Gun Squadron (to be formed) "W" Battery, RHA (not yet arrived from India) No. 5 Field Troop, 1st Sappers & Miners (to be formed) 11th Cavalry Brigade Signal Troop (forming) 11th Cavalry Brigade Supply & Transport Company (not yet arrived from India) No. 152 Cavalry Combined Field Ambulance (not yet arrived from India) No. 8 Mobile Veterinary Section (at Basra) 1st Indian Army Corps: (HQ at Samarra) 3rd (Lahore) Division: (HQ at Samarra) 7th Infantry Brigade: 1/Connaught Rangers 27th Punjabis 91st Punjabis 2/7th Gurkhas No. 131 Machine Gun Company 1 7th Brigade Supply & Transport Company 8th Infantry Brigade: 1/Manchester Regiment 47th Sikhs 59th Rifles 2/124th Baluchistan Infantry No. -

S. No Department DDO Code DDO Description Personal No Employee Name Position Code Designation BPS NIC Date of Birth Date Of

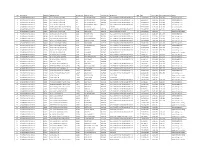

S. No Department DDO Code DDO Description Personal No Employee Name Position code Designation BPS NIC Date of Birth Date of Appointment Remarks 1 ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE AD4021 Sr CIVIL JUDGE ATD (P.S. ESTB) 639 MUHAMMAD YOUNAS. 80005264 AGS DESIGNATION NOT RECONCILED WITH FD 6 1310108501063 12.04.1960 22.04.1985 Incorrect Designation 2 ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE AD4021 Sr CIVIL JUDGE ATD (P.S. ESTB) 645 MUHAMMAD SHARIF. 80005268 AGS DESIGNATION NOT RECONCILED WITH FD 6 12162918521 05.05.1962 17.03.1987 Incorrect Designation 3 ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE AD4021 Sr CIVIL JUDGE ATD (P.S. ESTB) 647 MUHAMMAD ASGHAR. 80005269 AGS DESIGNATION NOT RECONCILED WITH FD 6 1310133885715 20.05.1963 16.05.1981 Incorrect Designation 4 ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE AD4021 Sr CIVIL JUDGE ATD (P.S. ESTB) 655 MUHAMMAD RIAZ KHAN. 80005271 AGS DESIGNATION NOT RECONCILED WITH FD 6 1310109491705 20.04.1967 18.12.1988 Incorrect Designation 5 ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE PR4079 DISTRICT AND SESSION JUDGE PESHAWAR. 26700 RAJ KAPOOR SWEEPER 4 9999901003299 02.10.1973 02.10.1993 Missing/Dummy NIC 6 ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE PR4080 DISTRICT AND SESSION JUDGE PESHAWAR. 37074 MUHAMMAD QASAM 80309540 AGS DESIGNATION NOT RECONCILED WITH FD 6 1730140765203 15.04.1966 14.09.1991 Incorrect Designation 7 ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE SW7201 Anti Terrorism Courts-III, Swat. 37087 SHAHID KHAN 80586017 DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE 21 1710103525845 25.09.1962 Appointment Date missing 8 ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE SW4038 SR.CIVIL JUDGE SWAT(P.S.ESTAB) 65826 HAROON RASHID 80235493 AGS DESIGNATION -

Masterly Inactivity’: Lord Lawrence, Britain and Afghanistan, 1864-1879

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ ‘Masterly inactivity’: Lord Lawrence, Britain and Afghanistan, 1864-1879 Wallace, Christopher Julian Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 1 ‘Masterly inactivity’: Lord Lawrence, Britain and Afghanistan, 1864-1879 Christopher Wallace PhD History June 2014 2 Abstract This dissertation examines British policy in Afghanistan between 1864 and 1879, with particular emphasis on Sir John Lawrence’s term as governor-general and viceroy of India (1864-69). -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Tehsil Municipal Administrations in District Dir Upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Audit Year 2016-17 Au

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF TEHSIL MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATIONS IN DISTRICT DIR UPPER KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA AUDIT YEAR 2016-17 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................................... i PREFACE ........................................................................................................................ ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. iii SUMMARY TABLES AND CHARTS .......................................................................... vi I: Audit Work Statistics .......................................................................................... vi II: Audit observations classified by Categories ...................................................... vi III: Outcome Statistics ........................................................................................... vii IV: Irregularities pointed out ................................................................................viii V: Cost-Benefit ....................................................................................................viii CHAPTER-1 .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Tehsil Municipal Administrations in District Upper Dir ......................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 1.1.2