Principles of Modern American Counterinsurgency: Evolution And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar M AY 2014 Above: Behsud Bridge, Nangarhar Province (Photo by TLO) A TLO M A P P I N G R EPORT Justice and Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar May 2014 In Cooperation with: © 2014, The Liaison Office. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, The Liaison Office. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] ii Acknowledgements This report was commissioned from The Liaison Office (TLO) by Cordaid’s Security and Justice Business Unit. Research was conducted via cooperation between the Afghan Women’s Resource Centre (AWRC) and TLO, under the supervision and lead of the latter. Cordaid was involved in the development of the research tools and also conducted capacity building by providing trainings to the researchers on the research methodology. While TLO makes all efforts to review and verify field data prior to publication, some factual inaccuracies may still remain. TLO and AWRC are solely responsible for possible inaccuracies in the information presented. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cordaid. The Liaison Office (TL0) The Liaison Office (TLO) is an independent Afghan non-governmental organization established in 2003 seeking to improve local governance, stability and security through systematic and institutionalized engagement with customary structures, local communities, and civil society groups. -

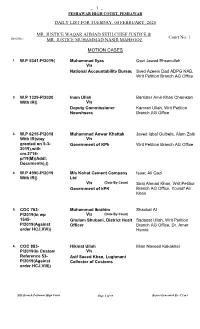

Db List for 04-02-2020(Tuesday)

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE MUHAMMAD NASIR MAHFOOZ MOTION CASES 1. W.P 5341-P/2019() Muhammad Ilyas Qazi Jawad Ehsanullah V/s National Accountability Bureau Syed Azeem Dad ADPG NAB, Writ Petition Branch AG Office 2. W.P 1329-P/2020 Inam Ullah Barrister Amir Khan Chamkani With IR() V/s Deputy Commissioner Kamran Ullah, Writ Petition Nowshsera Branch AG Office 3. W.P 6215-P/2018 Muhammad Anwar Khattak Javed Iqbal Gulbela, Alam Zaib With IR(stay V/s granted on 5-3- Government of KPk Writ Petition Branch AG Office 2019),with cm.2715- p/19(M)(Addl: Documents),() 4. W.P 4990-P/2019 M/s Kohat Cement Company Isaac Ali Qazi With IR() Ltd V/s (Date By Court) Siraj Ahmad Khan, Writ Petition Government of kPK Branch AG Office, Yousaf Ali Khan 5. COC 763- Muhammad Ibrahim Shaukat Ali P/2019(in wp V/s (Date By Court) 1545- Ghulam Shubani, District Health Sadaqat Ullah, Writ Petition P/2019(Against Officer Branch AG Office, Dr. Amer order HCJ,XVI)) Hamid 6. COC 883- Hikmat Ullah Mian Naveed Kakakhel P/2019(in Custom V/s Reference 53- Asif Saeed Khan, Lughmani P/2019(Against Collector of Customs order HCJ,VIII)) MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 88 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. -

Title Changing Gender Relations on Return from Displacement to The

HPG Report/WorkingHPG Working Paper Changing gender relations on return from displacementTitle to the Subtitlenewly merged districts Authorsof Pakistan Simon Levine Date October 2020 About the author Simon Levine is a Senior Research Fellow at the Humanitarian Policy Group (HPG) at ODI. Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without a dedicated team of researchers who did not simply conduct the interviews: they managed the whole process of fieldwork and shaped the analysis in this paper by combining their deep familiarity with the area with a very sharp analysis of the changes they saw happening. They know who they are, and they know how great is my debt to them. Thanks, too, to Megan Daigle, Kerrie Holloway and Sorcha O’Callaghan for comments on earlier drafts; and to the (anonymous) peer reviewers who generously gave up their time to give an incisive critique that helped this to become a better paper. Katie Forsythe worked her editing magic, as always; and Hannah Bass ensured that the report made it swiftly through production, looking perfect. Thanks also to Catherine Langdon, Sarah Cahoon and Isadora Brizolara for facilitating the project. The core of HPG’s work is its Integrated Programme (IP), a two-year body of research spanning a range of issues, countries and emergencies, allowing it to examine critical issues facing humanitarian policy and practice and influence key debates in the sector. This paper is part of HPG’s 2019–2021 IP, ‘Inclusivity and invisibility in humanitarian action’. The author would like to thank HPG’s IP donors, whose funding enables this research agenda. -

Articles Al-Qaida and the Pakistani Harakat Movement: Reflections and Questions About the Pre-2001 Period by Don Rassler

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 11, Issue 6 Articles Al-Qaida and the Pakistani Harakat Movement: Reflections and Questions about the pre-2001 Period by Don Rassler Abstract There has been a modest amount of progress made over the last two decades in piecing together the developments that led to creation of al-Qaida and how the group has evolved over the last 30 years. Yet, there are still many dimensions of al-Qaida that remain understudied, and likely as a result, poorly understood. One major gap are the dynamics and relationships that have underpinned al-Qaida’s multi-decade presence in Pakistan. The lack of developed and foundational work done on the al-Qaida-Pakistan linkage is quite surprising given how long al- Qaida has been active in the country, the mix of geographic areas - from Pakistan’s tribal areas to its main cities - in which it has operated and found shelter, and the key roles Pakistani al-Qaida operatives have played in the group over the last two decades. To push the ball forward and advance understanding of this critical issue, this article examines what is known, and has been suggested, about al-Qaida’s relations with a cluster of Deobandi militant groups consisting of Harakat ul-Mujahidin, Harakat ul-Jihad Islami, Harakat ul-Ansar, and Jaish-e-Muhammad, which have been collectively described as Pakistan’s Harakat movement, prior to 9/11. It finds that each of these groups and their leaders provided key elements of support to al-Qaida in a number of direct and indirect ways. -

Dr Javed Iqbal Introduction IPRI Journal XI, No. 1 (Winter 2011): 77-95

An Overview of BritishIPRI JournalAdministrativeXI, no. Set-up 1 (Winter and Strategy 2011): 77-95 77 AN OVERVIEW OF BRITISH ADMINISTRATIVE SET-UP AND STRATEGY IN THE KHYBER 1849-1947 ∗ Dr Javed Iqbal Abstract British rule in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, particularly its effective control and administration in the tribal belt along the Pak-Afghan border, is a fascinating story of administrative genius and pragmatism of some of the finest British officers of the time. The unruly land that could not be conquered or permanently subjugated by warriors and conquerors like Alexander, Changez Khan and Nadir Shah, these men from Europe controlled and administered with unmatched efficiency. An overview of the British administrative set-up and strategy in Khyber Agency during the years 1849-1947 would help in assessing British strengths and weaknesses and give greater insight into their political and military strategy. The study of the colonial system in the tribal belt would be helpful for administrators and policy makers in Pakistan in making governance of the tribal areas more efficient and effective particularly at a turbulent time like the present. Introduction ome facts of history have been so romanticized that it would be hard to know fact from fiction. British advent into the Indo-Pakistan S subcontinent and their north-western expansion right up to the hard and inhospitable hills on the Western Frontier of Pakistan is a story that would look unbelievable today if one were to imagine the wildness of the territory in those times. The most fascinating aspect of the British rule in the Indian Subcontinent is their dealing with the fierce and warlike tribesmen of the northwest frontier and keeping their land under their effective control till the very end of their rule in India. -

DOSTUM: AFGHANISTAN’S EMBATTLED WARLORD by Brian Glyn Williams

VOLUME VI, ISSUE 8 APRIL 17, 2008 IN THIS ISSUE: DOSTUM: AFGHANISTAN’S EMBATTLED WARLORD By Brian Glyn Williams....................................................................................1 SINO-PAKISTANI DEFENSE RELATIONS AND THE WAR ON TERRORISM By Tariq Mahmud Ashraf................................................................................4 CAPABILITIES AND RESTRAINTS IN TURKEY’S COUNTER-TERRORISM POLICY By Gareth Jenkins...........................................................................................7 AL-QAEDA’S PALESTINIAN INROADS Abdul Rashid Dostum By Fadhil Ali....................................................................................................10 Terrorism Monitor is a publication of The Jamestown Foundation. Dostum: Afghanistan’s Embattled Warlord The Terrorism Monitor is designed to be read by policy- By Brian Glyn Williams makers and other specialists yet be accessible to the general While the resurgence of the Taliban is the focus of interest in the Pashtun south public. The opinions expressed within are solely those of the of Afghanistan, the year started with a different story in the north that many are authors and do not necessarily depicting as one of the greatest challenges to the Karzai government. Namely the reflect those of The Jamestown surreal confrontation between General Abdul Rashid Dostum, the larger-than- Foundation. life Uzbek jang salar (warlord)—who was once described as “one of the best equipped and armed warlords ever”—and one of his former aides [1]. In a move that many critics of the situation in Afghanistan saw as epitomizing Unauthorized reproduction or the Karzai government’s cravenness in dealing with brutal warlords, the Afghan redistribution of this or any government backed away from arresting Dostum after he beat up and kidnapped Jamestown publication is strictly a former election manager and spokesman in Kabul on February 3 (IHT, February prohibited by law. -

Mr. Ahmed Rashid Journalist Current Afghanistan-Pakistan Affairs

JIIA Forum Summary of Lecture Friday, April 2, 2010 “Aso” Hall, The Tokai University Club, 35th Floor, Kasumigaseki Bldg Mr. Ahmed Rashid Journalist Current Afghanistan-Pakistan Affairs Introduction I would like to take this opportunity today to speak on three topics: the situation in Afghanistan, developments in Pakistan, and Japan’s policy toward Afghanistan. I will also include some policy suggestions with each of these. 1.The current situation in Afghanistan Recent years have seen a striking expansion of Taliban power in Afghanistan, and independent authoritative bodies that might well be termed “shadow governments” have been formed in 30 of the country’s 34 states. In fact, the situation differs greatly from that of the 1990s in that the Taliban have incited actions by Islamic fundamentalist groups across the region and that similar terrorist acts are being committed even in Central Asia and India. However, this expansion of Taliban power relies more on oppression, fear and terror than on popular support, reflecting the Karzai government’s limited capacity to implement policy as well as reduced aid from overseas. In other words, adequately thwarting the resurgence of the Taliban depends on Western strategy. Today’s situation could be seen as the cumulative result of strategic blunders, including the cut in aid and the slowdown in economic reconstruction in the wake of the war in Iraq, the greater effort focused by the Bush administration on bringing down Al Qaeda than the Taliban, the provision of safe havens to the Taliban by Pakistan, and the adverse impact of hasty implementation of the peace process on domestic and international confidence. -

AFGHANISTAN La Situation Sécuritaire À Jalalabad

COMMISSARIAT-GÉNÉRAL AUX RÉFUGIÉS ET AUX APATRIDES COI Focus AFGHANISTAN La situation sécuritaire à Jalalabad 20 février 2018 (Mise à jour) Cedoca Langue du document original: néerlandais DISCLAIMER: Ce document COI a été rédigé par le Centre de documentation et de This COI-product has been written by Cedoca, the Documentation and recherches (Cedoca) du CGRA en vue de fournir des informations pour le Research Department of the CGRS, and it provides information for the traitement des demandes d’asile individuelles. Il ne traduit aucune politique processing of individual asylum applications. The document does not contain ni n’exprime aucune opinion et ne prétend pas apporter de réponse définitive policy guidelines or opinions and does not pass judgment on the merits of quant à la valeur d’une demande d’asile. Il a été rédigé conformément aux the asylum application. It follows the Common EU Guidelines for processing lignes directrices de l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information country of origin information (April 2008) and is written in accordance with sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008). the statutory legal provisions. Ce document a été élaboré sur la base d’un large éventail d’informations The author has based the text on a wide range of public information selected publiques soigneusement sélectionnées dans un souci permanent de with care and with a permanent concern for crosschecking sources. Even recoupement des sources. L’auteur s’est efforcé de traiter la totalité des though the document tries to cover all the relevant aspects of the subject, the aspects pertinents du sujet mais les analyses proposées ne visent pas text is not necessarily exhaustive. -

Genetic Analysis of the Major Tribes of Buner and Swabi Areas Through Dental Morphology and Dna Analysis

GENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE MAJOR TRIBES OF BUNER AND SWABI AREAS THROUGH DENTAL MORPHOLOGY AND DNA ANALYSIS MUHAMMAD TARIQ DEPARTMENT OF GENETICS HAZARA UNIVERSITY MANSEHRA 2017 I HAZARA UNIVERSITY MANSEHRA Department of Genetics GENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE MAJOR TRIBES OF BUNER AND SWABI AREAS THROUGH DENTAL MORPHOLOGY AND DNA ANALYSIS By Muhammad Tariq This research study has been conducted and reported as partial fulfillment of the requirements of PhD degree in Genetics awarded by Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan Mansehra The Friday 17, February 2017 I ABSTRACT This dissertation is part of the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (HEC) funded project, “Enthnogenetic elaboration of KP through Dental Morphology and DNA analysis”. This study focused on five major ethnic groups (Gujars, Jadoons, Syeds, Tanolis, and Yousafzais) of Buner and Swabi Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan, through investigations of variations in morphological traits of the permanent tooth crown, and by molecular anthropology based on mitochondrial and Y-chromosome DNA analyses. The frequencies of seven dental traits, of the Arizona State University Dental Anthropology System (ASUDAS) were scored as 17 tooth- trait combinations for each sample, encompassing a total sample size of 688 individuals. These data were compared to data collected in an identical fashion among samples of prehistoric inhabitants of the Indus Valley, southern Central Asia, and west-central peninsular India, as well as to samples of living members of ethnic groups from Abbottabad, Chitral, Haripur, and Mansehra Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and to samples of living members of ethnic groups residing in Gilgit-Baltistan. Similarities in dental trait frequencies were assessed with C.A.B. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Kurram Agency

Overview - Kurram Agency Legend !^! Toymela ! National Toi Mela ! Rekhmin Dhand !!! ! Durrani Durani Province ! Sobha Mala Sooha Mela Bughak Uhand ! ! Mirmai ! Bughak Gujarghuna Ghujarghunda ! ! ! Paiki ! Dinga Mela Dhand Hussain !! ! ! Ana Mela Khairwa Mela ! Darwekkai ! District Chrungo ! ! Khair-ud-din Watagh Shapoabad ! ! ! Chhapri Landi Ragha Mela Babi Kotkai Mela ! Shafu Kheradin ! ! Nari Khewas Mela Khan Shah ! ! ! ! Mandakai Gulab Mela ! Ad Mela ! Kas ! Mela Jiwan Shian Jabe Mela Kotkai Mandalai ! ! ! Ismail Mela Maikai ! Maikai RH Mela ! ! Kas ! Chapri Khalil Mela Mela ! ! ! Lali Mela Settlements Mullano Kili ! Mullano Kalai Kabuli Mela ! ! ! Zarnao Mela ! Cherai Gobazana Tutki Mela ! ! ! Gido ! Kambar ! Kotri Teri Ghundi Khel Chapri ! Chinanao ! ! Ali Rabuli Mela ! Maikai Kili Qliinanao Alizai Kili Chhapri Duparzai ! ! ! ! Kambar Ali Landikas ! Ali Mangal Sorai Mela Ali Kalai Azizo Mela Rest House Ganda Kili ! Ganda Kalai Luqman Kel Khanai ! ! Mangal ! ! ! Chhapri Kili Kotkai ! Khamzai ! Wasai Ali Kotkar Dargah Kili Luqman ! ! Bar Dap Mullah Mulla Post Kulalano Kili ! ! Darawai Landiwan ! Mangal ! Khel Bagh ! Bagh Administartive Boundaries Sursurang ! Karpachi Kulalano All Sheri ! Lar Dap ! ! Kaskai Kili ! Tarsi Kalai Tarsi Kili ! Karezgai Malana ! Karpachi Arghania Khunekai Kalai Ali Sheri ! ! Raju Karezgal ! Jalamzokot Kili ! Bara Darra Khunekal Fuladai Arghanja Kili ! ! Mela ! ! Khaurai ! ! Amad Shah Kali ! Daradar Haqdarra Yusuf Kili Yusuf Kalai ! Lara Darra Shinesar ! Dagoi Shalozan ! ! ! Alimanza ! Sahra Qubad Shah Khel -

Strange Victory: a Critical Appraisal of Operation Enduring Freedom and the Afghanistan War

30 JANUARY 2002 RESEARCH MONOGRAPH #6 Strange Victory: A critical appraisal of Operation Enduring Freedom and the Afghanistan war Carl Conetta PROJECT ON DEFENSE ALTERNATIVES COMMONWEALTH INSTITUTE, CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS Contents Introduction 3 1. What has Operation Enduring Freedom accomplished? 4 1.1 The fruits of victory 4 1.1.1 Secondary goals 5 1.2 The costs of the war 6 1.2.1 The humanitarian cost of the war 7 1.2.2 Stability costs 7 2. Avoidable costs: the road not taken 9 3. War in search of a strategy 10 3.1 The Taliban become the target 10 3.2 Initial war strategy: split the Taliban 12 3.2.1 Romancing the Taliban 13 3.2.2 Pakistan: between the devil and the red, white, and blue 14 3.3 The first phase of the air campaign: a lever without a fulcrum 15 3.3.1 Strategic bombardment: alienating hearts and minds 15 3.4 A shift in strategy -- unleashing the dogs of war 17 4. A theater redefined 18 4.1 Reshuffling Afghanistan 19 4.2 Regional winners and losers 20 4.3 The structure of post-war Afghan instability 21 4.3.1 The Bonn agreement: nation-building or “cut and paste”? 22 4.3.2 Peacekeepers for Afghanistan: too little, too late 24 4.4 A new game: US and Afghan interests diverge 25 4.4.1 A failure to adjust 26 5. The tunnel at the end of the light 28 5.1 The path charted by Enduring Freedom 28 5.2 The triumph of expediency 29 5.3 The ascendancy of Defense 29 5.4 Realism redux 31 5.5 Bread and bombs 32 5.6 The fog of peace 34 Appendix 1.