Militancy in Pakistan's Borderlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Foreign Fighters Problem, Recent Trends and Case Studies: Selected Essays

Program on National Security at the FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Al-Qaeda al-Shabaab AQIM AQAP Central The Foreign Fighters Problem, Recent Trends and Case Studies: Selected Essays Edited by Michael P. Noonan Managing Director, Program on National Security April 2011 Copyright Foreign Policy Research Institute (www.fpri.org). If you would like to be added to our mailing list, send an email to [email protected], including your name, address, and any affiliation. For further information or to inquire about membership in FPRI, please contact Alan Luxenberg, [email protected] or (215) 732-3774 x105. FPRI 1528 Walnut Street, Suite 610 • Philadelphia, PA 19102-3684 Tel. 215-732-3774 • Fax 215-732-4401 About FPRI Founded in 1955, the Foreign Policy Research Institute is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests. We add perspective to events by fitting them into the larger historical and cultural context of international politics. About FPRI’s Program on National Security The end of the Cold War ushered in neither a period of peace nor prolonged rest for the United States military and other elements of the national security community. The 1990s saw the U.S. engaged in Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, and numerous other locations. The first decade of the 21st century likewise has witnessed the reemergence of a state of war with the attacks on 9/11 and military responses (in both combat and non-combat roles) globally. While the United States remains engaged against foes such as al-Qa`ida and its affiliated movements, other threats, challengers, and opportunities remain on the horizon. -

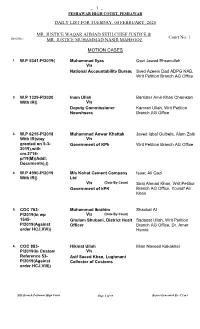

Db List for 04-02-2020(Tuesday)

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE MUHAMMAD NASIR MAHFOOZ MOTION CASES 1. W.P 5341-P/2019() Muhammad Ilyas Qazi Jawad Ehsanullah V/s National Accountability Bureau Syed Azeem Dad ADPG NAB, Writ Petition Branch AG Office 2. W.P 1329-P/2020 Inam Ullah Barrister Amir Khan Chamkani With IR() V/s Deputy Commissioner Kamran Ullah, Writ Petition Nowshsera Branch AG Office 3. W.P 6215-P/2018 Muhammad Anwar Khattak Javed Iqbal Gulbela, Alam Zaib With IR(stay V/s granted on 5-3- Government of KPk Writ Petition Branch AG Office 2019),with cm.2715- p/19(M)(Addl: Documents),() 4. W.P 4990-P/2019 M/s Kohat Cement Company Isaac Ali Qazi With IR() Ltd V/s (Date By Court) Siraj Ahmad Khan, Writ Petition Government of kPK Branch AG Office, Yousaf Ali Khan 5. COC 763- Muhammad Ibrahim Shaukat Ali P/2019(in wp V/s (Date By Court) 1545- Ghulam Shubani, District Health Sadaqat Ullah, Writ Petition P/2019(Against Officer Branch AG Office, Dr. Amer order HCJ,XVI)) Hamid 6. COC 883- Hikmat Ullah Mian Naveed Kakakhel P/2019(in Custom V/s Reference 53- Asif Saeed Khan, Lughmani P/2019(Against Collector of Customs order HCJ,VIII)) MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 88 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

The Jirga: Justice and Conflict Transformation

REPORT Security in South Asia CAMP (Community Appraisal and Motivation Programme) and Saferworld The Jirga: justice and conflict transformation March 2012 The Jirga: justice and conflict transformation COMMUNITY APPRAISAL AND MOTIVATION PROGRAMME and SAFERWORLD MARCH 2012 Acknowledgements This report represents an analysis of primary research commissioned by Community Appraisal and Motivation Programme (CAMP) and Saferworld in Pakistan during 2011. This report was co-authored by Christian Dennys and Marjana. This publication was designed by Jane Stevenson, and prepared under the People’s Peacemaking Perspectives Project. Particular thanks for their inputs into the research process go to Aezaz Ur Rehman, Neha Gauhar, Riaz-ul-Haq, Habibullah Baig, Naveed Shinwari and Fareeha Sultan from CAMP and Rosy Cave, Chamila Hemmathagama, Paul Murphy and Evelyn Vancollie from Saferworld. CAMP and Saferworld would like to thank officials from Government of Pakistan, members of civil society and all those people living in Lower Dir and Swat who shared their views and opinions despite the sensitive nature of the topic. We are grateful to the European Union (EU) for its financial support for this project. The People’s Peacemaking Perspectives project The People’s Peacemaking Perspectives project is a joint initiative implemented by Conciliation Resources and Saferworld and financed under the European Commission’s Instrument for Stability. The project provides European Union institutions with analysis and recommendations based on the opinions and experiences of local people in a range of countries and regions affected by fragility and violent conflict. © Saferworld March 2012. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution. -

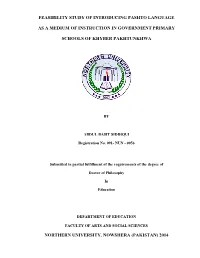

Feasibility Study of Introducing Pashto Language As a Medium of Instruction in the Government Primary Schools of Khyber

FEASIBILITY STUDY OF INTRODUCING PASHTO LANGUAGE AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION IN GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOLS OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA BY ABDUL BASIT SIDDIQUI Registration No. 091- NUN - 0056 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Education DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES NORTHERN UNIVERSITY, NOWSHERA (PAKISTAN) 2014 i ii DEDICATION To my dear parents, whose continuous support, encouragement and persistent prayers have been the real source of my all achievements. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT xv ABSTRACT xvii Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM 2 1.2 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY 3 1.3 HYPOTHESIS OF THE STUDY 3 1.4 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY 3 1.5 DELIMITATION OF THE STUDY 4 1.6 METHOD AND PROCEDURE 4 1.6.1 Population 4 1.6.2 Sample 4 1.6.3 Research Instruments 5 1.6.4 Data Collection 5 1.6.5 Analysis of Data 5 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE 6 2.1 ALL CREATURES OF THE UNIVERSE COMMUNICATE 7 2.2 LANGUAGE ESTABLISHES THE SUPERIORITY OF HUMAN BEINGS OVER OTHER SPECIES OF THE WORLD 8 2.3 DEFINITIONS: 9 2.3.1 Mother Tongue / First Language 9 2.3.2 Second Language (L2) 9 2.3.3 Foreign Language 10 2.3.4 Medium of Instruction 10 iv 2.3.5 Mother Tongue as a Medium of Instruction 10 2.4 HOW CHILDREN LEARN THEIR MOTHER TONGUE 10 2.5 IMPORTANT CHARACTERISTICS FOR A LANGUAGE ADOPTED AS MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION 11 2.6 CONDITIONS FOR THE SELECTION OF DESIRABLE TEXT FOR LANGUAGE 11 2.7 THEORIES ABOUT LEARNING (MOTHER) LANGUAGE 12 2.8 ORIGIN OF PAKHTUN -

Text in Community Study Guide

Text in Community Study Guide I am Malala—Malala Yousafzai w/ Christine Lamb Created by—Dr. Michael K. Cundall, Jr., Darrell Hairston, and Anna Whiteside: University Honors Program Prologue: The Day My World Changed/ Chapter 1: A Daughter is Born 1) Why do so few people in Pakistan celebrate the birth of a baby girl? What is the attitude of Malala’s father’s toward the birth his daughter? 2) After whom is Malala named? 3) What are society’s expectations of girls? What are the attitudes of Malala and her father about the role of girls in society? 4) Before she was shot, did Malala fear for her own life? 5) Why do you think the KPK is independent? Does this cultural and geographical independence from the main part of Pakistan mean anything for the rest of Malala’s story? 6) What did Alexander the Great do when he reached the Swat Valley? 7) What are the various religions that have “ruled” the Swat Valley? The Swat Valley, Malala’ Yousafzai’s hometown, is known for its mountains, meadows, and lakes. Tourists often call it “the Switzerland of the East.” The Swat Valley was the home of Pakistan’s first ski resort. (Map Showing the Location of Swat District, Source: Pahari Sahib, Wikimedia Commons) The SWAT valley’s population is mostly made up of ethnic Gujjar and Pashtuns. The Yousafzais are Pashtuns, a group whose population is located primarily in Afghanistan and northwestern and western parts of Iran. (Ghabral, Swat Valley. Source: Isrum, Wikimedia Commons) (Mahu Dan Swat Valley, Source: Isruma, Wikimedia Commons) (Snow covered mountain in Sway Valley, Source: Isruma, Wikimedia Commons) The Swat valley is home to several relics left over from the Buddhist Reign in the third century BC. -

The Terrorism Trap: the Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2019 The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror John Akins University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Akins, John, "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5624 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by John Akins entitled "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Krista Wiegand, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Brandon Prins, Gary Uzonyi, Candace White Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America’s War on Terror A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville John Harrison Akins August 2019 Copyright © 2019 by John Harrison Akins All rights reserved. -

Washington, DC June 1, 2016 Dear Mr. President, We Are Writing, As

Washington, DC June 1, 2016 Dear Mr. President, We are writing, as Americans committed to the success of our country’s Afghanistan mission, to urge that you sustain the current level of U.S. forces in Afghanistan through the remainder of your term. Aid levels and diplomatic energies should similarly be preserved without reduction. Unless emergency conditions require consideration of a modest increase, we would strongly favor a freeze at the level of roughly 10,000 U.S. troops through January 20. This approach would also allow your successor to assess the situation for herself or himself and make further adjustments accordingly. The broader Middle East is roiled in conflicts that pit moderate and progressive forces against those of violent extremists. As we saw on 9/11 and in the recent attacks in Paris, San Bernardino, and Brussels, the problems of the Middle East do not remain contained within the Middle East. Afghanistan is the place where al Qaeda and affiliates first planned the 9/11 attacks and a place where they continue to operate—and is thus important in the broader effort to defeat the global extremist movement today. It is a place where al Qaeda and ISIS still have modest footprints that could be expanded if a security vacuum developed. If Afghanistan were to revert to the chaos of the 1990s, millions of refugees would again seek shelter in neighboring countries and overseas, dramatically intensifying the severe challenges already faced in Europe and beyond. In the long-term struggle against violent extremists, the United States above all needs allies—not only to fight a common enemy, but also to create a positive vision for the peoples of the region. -

Cultural Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution

Cultural Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution Introduction In his poem, The Second Coming (1919), William Butler Yeats captured the moment we are now experiencing: Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. As we see the deterioration of the institutions created and fostered after the Second World War to create a climate in which peace and prosperity could flourish in Europe and beyond, it is important to understand the role played by diplomacy in securing the stability and strengthening the shared values of freedom and democracy that have marked this era for the nations of the world. It is most instructive to read the Inaugural Address of President John F. Kennedy, in which he encouraged Americans not only to do good things for their own country, but to do good things in the world. The creation of the Peace Corps is an example of the kind of spirit that put young American volunteers into some of the poorest nations in an effort to improve the standard of living for people around the globe. We knew we were leaders; we knew that we had many political and economic and social advantages. There was an impetus to share this wealth. Generosity, not greed, was the motivation of that generation. Of course, this did not begin with Kennedy. It was preceded by the Marshall Plan, one of the only times in history that the conqueror decided to rebuild the country of the vanquished foe. -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert L. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-319-8 doi: 10.2847/639900 © European Asylum Support Office 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: FATA Faces FATA Voices, © FATA Reforms, url, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT PAKISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the Belgian Center for Documentation and Research (Cedoca) in the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, as the drafter of this report. Furthermore, the following national asylum and migration departments have contributed by reviewing the report: The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Hungary, Office of Immigration and Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Office Documentation Centre Slovakia, Migration Office, Department of Documentation and Foreign Cooperation Sweden, Migration Agency, Lifos -

2013 Newsletter

Past, Present & Future THE 2013 REPORT FROM THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY A Week With Writer-In-Residence Robin D.G. Kelley Each year the Department of History brings a writer of national prominence to campus for a weeklong residency. The aim of the visit is to help our students and faculty think more purposefully about how to bring our work to the public in as many ways as we are able. In March the department was thrilled to welcome Robin D.G. Kelley, Gary B. Nash Professor of American History at UCLA, as our spring 2013 Writer-in-Residence. Kelley’s research and teaching interests span the history of labor and radical movements in the U.S., the African Diaspora, and Africa; intellectual and cultural history, particularly music and visual culture; urban studies, and transnational movements. He is perhaps best known for his popular books Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original and Yo Mama’s DisFunktional!: Fighting the Culture Wars in Urban America. Before arriving at UMass, Kelley volunteered to give two major lectures—one at UMass and one at Amherst College— rather than the customary single public talk. Both talks— “The Long Rise and Short Decline of American Democracy” and “Seeking Soul Sister: Grace Halsell and the Quest for a Compassionate World”—played to packed houses. Kelley later shared early insights from his current book project, a biography of Grace Halsell, a white journalist known for her experiments in racial and cultural crossing. (If you missed these great events, not to worry: the lecture given here on campus—an excellent companion to our 2012-13 Feinberg Series, “Truth Robin D.G.