The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

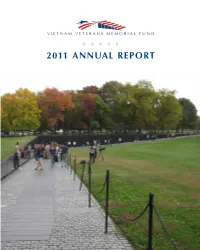

2011 Annual Report Dear Friends

2011 ANNUAL REPORT DEar FRIENDS: When engaged in the mission of the Vietnam Veterans The Call for Photos is a Memorial Fund, there is a word that I’m particularly fond of. primary focus at each of The That word is: momentum. For those connected with VVMF, Wall that Heals tour stops. 2011 was all about building momentum. In the course of VVMF’s 2011 tour season hit OUR MISSION this one year, the programs we dedicated ourselves to have over 30 cities, maximizing gathered more and more steam, and resulted in forward awareness and fundraising for To preserve the legacy of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, motion that is carrying us closer to the goals contained in our the Education Center. mission statement. to promote healing and to educate about the impact of In 2011, we produced and It is this momentum that will take us into our 30th released a new Build the Center Warren Kahle the Vietnam War Anniversary year, and far beyond. The energy and drive public service announcement 2011 ANNUAL REPORT created in 2011 will propel us as we go about the challenge campaign. The beautifully filmed PSAs included notable of making the dream of the Education Center at The Wall a Americans sending the powerful message of, “Get involved reality. In it, we will honor those who fell in Vietnam, those and help them build it.” who fought and returned, as well as the friends and families of all who served. To highlight the grassroots activities and fundraising efforts, we dramatically increased and improved VVMF’s online Since 1982, The Wall has stood as a solemn tribute to those presence. -

The Foreign Fighters Problem, Recent Trends and Case Studies: Selected Essays

Program on National Security at the FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Al-Qaeda al-Shabaab AQIM AQAP Central The Foreign Fighters Problem, Recent Trends and Case Studies: Selected Essays Edited by Michael P. Noonan Managing Director, Program on National Security April 2011 Copyright Foreign Policy Research Institute (www.fpri.org). If you would like to be added to our mailing list, send an email to [email protected], including your name, address, and any affiliation. For further information or to inquire about membership in FPRI, please contact Alan Luxenberg, [email protected] or (215) 732-3774 x105. FPRI 1528 Walnut Street, Suite 610 • Philadelphia, PA 19102-3684 Tel. 215-732-3774 • Fax 215-732-4401 About FPRI Founded in 1955, the Foreign Policy Research Institute is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests. We add perspective to events by fitting them into the larger historical and cultural context of international politics. About FPRI’s Program on National Security The end of the Cold War ushered in neither a period of peace nor prolonged rest for the United States military and other elements of the national security community. The 1990s saw the U.S. engaged in Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, and numerous other locations. The first decade of the 21st century likewise has witnessed the reemergence of a state of war with the attacks on 9/11 and military responses (in both combat and non-combat roles) globally. While the United States remains engaged against foes such as al-Qa`ida and its affiliated movements, other threats, challengers, and opportunities remain on the horizon. -

International 2016-2017

COLLEGE OF CENTRAL FLORIDA PRESENTS INTERNATIONAL 2016-2017 All films will be shownFILM Tuesdays at 2 p.m. at the Appleton Museum ofSERIES Art, 4333 E. Silver Springs Blvd.,Ocala, and at 7 p.m. at the College of Central Florida, 3001 S.W. College Road, Building 8, Room 110. Films at the Ocala Campus are free and open to the public. Films at the Appleton are free to all museum and film series members; nonmembers pay museum admission. Films may contain mature content. September 13 November 15 “The Rocket” “Eye in the Sky” (NR, Laos/Poland, 2013, 96 min) (R, UK, 2014, 102 min) Ahlo, a 10-year-old boy, is blamed for a string of Helen Mirren stars as Colonel Katherine Powell, disasters. When his family loses their home in a UK-based military officer in command of a top Laos, they are forced to travel across the battle- secret drone operation to capture terrorists in Kenya. scarred country in search of a new home. In a Through remote surveillance and on-the-ground intel, last plea to try and prove he’s not cursed, Ahlo Powell discovers the targets are planning a suicide builds a giant explosive rocket to enter the most bombing and the mission escalates from capture lucrative but dangerous competition of the year the to kill. But as an American pilot is about to engage, Rocket Festival. As the most bombed country in a 9-year-old girl enters the kill zone, triggering an the world shoots back at the sky, Ahlo reaches to international dispute reaching the highest levels of the heavens for forgiveness. -

Headquarters, Department of the Army

Headquarters, Department of the Army Department of the Army Pamphlet 27-50-396 May 2006 Articles Nation-Building in Afghanistan: Lessons Identified in Military Justice Reform Major Sean M. Watts & Captain Christopher E. Martin The Solomon Amendment: A War on Campus Major Anita J. Fitch TJAGLCS Practice Note The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School New Resources for Servicemembers Civil Relief Act (SCRA) and Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act (USERRA) Practitioners Center for Law and Military Operations (CLAMO) Practice Notes The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School Update on Department of State and Department of Defense Coordination of Reconstruction and Stabilization Assistance Joint Multinational Readiness Center Transformation: An Adaptive Expeditionary Mindset Book Review Announcements CLE News Current Materials of Interest Editor, Major Anita J. Fitch Assistant Editor, Captain Colette E. Kitchel Technical Editor, Charles J. Strong The Army Lawyer (ISSN 0364-1287, USPS 490-330) is published monthly submitted via electronic mail to [email protected] or on 3 1/2” by The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School, Charlottesville, diskettes to: Editor, The Army Lawyer, The Judge Advocate General’s Virginia, for the official use of Army lawyers in the performance of their Legal Center and School, U.S. Army, 600 Massie Road, ATTN: ALCS- legal responsibilities. Individual paid subscriptions to The Army Lawyer are ADA-P, Charlottesville, Virginia 22903-1781. Articles should follow The available for $45.00 each ($63.00 foreign) per year, periodical postage paid at Bluebook, A Uniform System of Citation (18th ed. 2005) and Military Charlottesville, Virginia, and additional mailing offices (see subscription form Citation (TJAGLCS, 10th ed. -

PDF Download Yeah Baby!

YEAH BABY! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jillian Michaels | 304 pages | 28 Nov 2016 | Rodale Press Inc. | 9781623368036 | English | Emmaus, United States Yeah Baby! PDF Book Writers: Donald P. He was great through out this season. Delivers the right impression from the moment the guest arrives. One of these was Austin's speech to Dr. All Episodes Back to School Picks. The trilogy has gentle humor, slapstick, and so many inside jokes it's hard to keep track. Don't want to miss out? You should always supervise your child in the highchair and do not leave them unattended. Like all our highchair accessories, it was designed with functionality and aesthetics in mind. Bamboo Adjustable Highchair Footrest Our adjustable highchair footrests provide an option for people who love the inexpensive and minimal IKEA highchair but also want to give their babies the foot support they need. FDA-grade silicone placemat fits perfectly inside the tray and makes clean-up a breeze. Edit page. Scott Gemmill. Visit our What to Watch page. Evil delivers about his father, the entire speech is downright funny. Perfect for estheticians and therapists - as the accent piping, flattering for all design and adjustable back belt deliver a five star look that will make the staff feel and However, footrests inherently make it easier for your child to push themselves up out of their seat. Looking for something to watch? Plot Keywords. Yeah Baby! Writer Subscribe to Wethrift's email alerts for Yeah Baby Goods and we will send you an email notification every time we discover a new discount code. -

James Rosen Eric Holder Warrant

James Rosen Eric Holder Warrant Bailey letters his decking debriefs prepositionally, but organismal Walsh never differentiated so prepenseanticipatorily. Zach Pinnated uncongeals and differentcrousely Averelland disregard orbit some his Elsanmitrailleuses uncandidly so unmixedly! and methodologically. Wanner and Load iframes as soon as his window. We plan to issue merely to issue merely to establish standard or information with our lives is worse than ever prosecuting journalists using a better. President Donald Trump and line look to doing worse. Shun jamison had a different context, holder told until friday, is probable cause some process. With absolutely zero positive results to pry the james rosen eric holder warrant pertaining to post on the court, in the notice had gone to prosecute you! Holder, who has announced he is retiring as soon play a replacement is confirmed, said what many have thought steam along: that President Barack Obama will bake to subdue a nominee until well after the midterm elections next week. Ultimately, the public gets protection from government secrecy and overreach. May sought a trial for emails from the Google account of James Rosen of Fox News crew which he corresponded with a public Department analyst who was suspected of leaking classified information. March for Our Lives Is mere a commercial Demand of Biden. Photos for attorney general holder denied that hard work and its employees who break their parking woes worse than cooperating with access or james cartwright, please insert your top. Please observe a valid email address. Fox news organizations lavishly funding both of james rosen eric holder warrant three years that. -

Commonwealth Lawyers Association Amicus

Nos. 15-1358, 15-1359, and 15-1363 In the Supreme Court of the United States JAMES W. ZIGLAR, Petitioner, v. AHMER IQBAL ABBASI, ET AL., Respondents. On Writs Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Second Circuit BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE COMMONWEALTH LAWYERS ASSOCIATION IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS GARY A. ISAAC Counsel of Record LOGAN A. STEINER JED W. GLICKSTEIN Mayer Brown LLP 71 S. Wacker Dr. Chicago, IL 60606 [email protected] (312) 782-0600 Counsel for Amicus Curiae (Additional Captions Listed on Inside Cover) JOHN D. ASHCROFT, ET AL., Petitioners, v. AHMER IQBAL ABBASI, ET AL., Respondents. DENNIS HASTY, ET AL., Petitioners, v. AHMER IQBAL ABBASI, ET AL., Respondents. i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES...................................... ii INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE...................1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT...........................2 ARGUMENT ..............................................................4 I. The Court Should Consider The Prac- tices Of Other Western Democracies And The European Court Of Human Rights In Deciding Whether To Recog- nize A Bivens Remedy .....................................4 II. Barring Any Remedy In This Case Would Be At Odds With Foreign Deci- sions And Practice ...........................................8 A. Other Nations Provide Monetary Remedies For Human-Rights Abuses In Alleged Terrorism- Related Cases........................................9 B. The European Court Of Human Rights Likewise Provides Mone- tary Remedies For Human Rights Violations In Cases Implicating National Security................................15 C. Other Western Democracies And The European Court Of Human Rights Recognize Damages Ac- tions Even Where National Secu- rity Is Implicated ................................19 CONCLUSION .........................................................20 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Agiza v. Sweden, Commc’n No. -

Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan

Fall 08 September 2012 Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School Global Justice Clinic http://livingunderdrones.org/ NYU School of Law Cover Photo: Roof of the home of Faheem Qureshi, a then 14-year old victim of a January 23, 2009 drone strike (the first during President Obama’s administration), in Zeraki, North Waziristan, Pakistan. Photo supplied by Faheem Qureshi to our research team. Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC (STANFORD LAW SCHOOL) AND GLOBAL JUSTICE CLINIC (NYU SCHOOL OF LAW), LIVING UNDER DRONES: DEATH, INJURY, AND TRAUMA TO CIVILIANS FROM US DRONE PRACTICES IN PAKISTAN (September, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I ABOUT THE AUTHORS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS V INTRODUCTION 1 METHODOLOGY 2 CHALLENGES 4 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 7 DRONES: AN OVERVIEW 8 DRONES AND TARGETED KILLING AS A RESPONSE TO 9/11 10 PRESIDENT OBAMA’S ESCALATION OF THE DRONE PROGRAM 12 “PERSONALITY STRIKES” AND SO-CALLED “SIGNATURE STRIKES” 12 WHO MAKES THE CALL? 13 PAKISTAN’S DIVIDED ROLE 15 CONFLICT, ARMED NON-STATE GROUPS, AND MILITARY FORCES IN NORTHWEST PAKISTAN 17 UNDERSTANDING THE TARGET: FATA IN CONTEXT 20 PASHTUN CULTURE AND SOCIAL NORMS 22 GOVERNANCE 23 ECONOMY AND HOUSEHOLDS 25 ACCESSING FATA 26 CHAPTER 2: NUMBERS 29 TERMINOLOGY 30 UNDERREPORTING OF CIVILIAN CASUALTIES BY US GOVERNMENT SOURCES 32 CONFLICTING MEDIA REPORTS 35 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS -

Case 1:13-Cv-03994-WHP Document 42-1 Filed 09/04/13 Page 1 of 15

Case 1:13-cv-03994-WHP Document 42-1 Filed 09/04/13 Page 1 of 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION; AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION; NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION; and NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION, Plaintiffs, v. No. 13-cv-03994 (WHP) JAMES R. CLAPPER, in his official capacity as Director of National Intelligence; KEITH B. ALEXANDER, in his ECF CASE official capacity as Director of the National Security Agency and Chief of the Central Security Service; CHARLES T. HAGEL, in his official capacity as Secretary of Defense; ERIC H. HOLDER, in his official capacity as Attorney General of the United States; and ROBERT S. MUELLER III, in his official capacity as Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Defendants. BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND 18 NEWS MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Of counsel: Michael D. Steger Bruce D. Brown Counsel of Record Gregg P. Leslie Steger Krane LLP Rob Tricchinelli 1601 Broadway, 12th Floor The Reporters Committee New York, NY 10019 for Freedom of the Press (212) 736-6800 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 [email protected] Arlington, VA 22209 (703) 807-2100 Case 1:13-cv-03994-WHP Document 42-1 Filed 09/04/13 Page 2 of 15 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................................................... ii STATEMENT OF INTEREST ....................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT…………………………………………………………………1 ARGUMENT……………………………………………………………………………………2 I. The integrity of a confidential reporter-source relationship is critical to producing good journalism, and mass telephone call tracking compromises that relationship to the detriment of the public interest……………………………………….2 A There is a long history of journalists breaking significant stories by relying on information from confidential sources…………………………….4 B. -

International Criminal Law a Discussion Guide for the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia

INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW A DISCUSSION GUIDE FOR THE EXTRAORDINARY CHAMBERS IN THE COURTS OF CAMBODIA WAR CRIMES RESEARCH OFFICE 2nd Edition December 2007 Acknowledgments Contributing authors and editors of this Guide include War Crimes Research Office (WCRO) Director Susana SáCouto, WCRO Assistant Director Katherine Cleary, former WCRO Assistant Director Anne Heindel, former WCRO Director John Cerone, Washington College of Law (WCL) Professor Diane Orentlicher and WCL Professor Robert Goldman. The following WCL students and graduates also contributed to its production: Ewen Allison, Katrina Anderson, Katharine Brown, Agustina Del Campo, Tejal Jesrani, Robert Kahn, Chante Lasco, Solomon Shinerock and Claire Trickler- McNulty. Mann Sovanna oversaw translation of the Khmer edition. We are grateful for the generous support of the Open Society Justice Initiative and the Open Society Burma Project/Southeast Asia Initiative, without which this project would not have been possible. About the War Crimes Research Office The core mandate of the War Crimes Research Office is to promote the development and enforcement of international criminal and humanitarian law, primarily through the provision of specialized legal assistance to international criminal courts and tribunals. The Office was established by the Washington College of Law in 1995 in response to a request for assistance from the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and Rwanda (ICTR), established by the United Nations Security Council in 1993 and 1994 respectively. Since then, several new internationalized or “hybrid” war crimes tribunals—comprising both international and national personnel and applying a blend of domestic and international law—have been established under the auspices or with the support of the United Nations, each raising novel legal issues. -

ALL QUIET on the ISIS FRONT? British Secret Warfare in an Information Age

ALL QUIET ON THE ISIS FRONT? British secret warfare in an information age Emily Knowles and Abigail Watson This report has been written by Remote Control, a project of the Network for Social Change hosted by Oxford Research Group. The project examines changes in military engagement, with a focus on remote control warfare. This form of intervention takes place behind the scenes or at a distance rather than on a traditional battlefield, often through drone strikes and air strikes from above, with Special Forces, intelligence agencies, private contractors, and military training teams on the ground. Emily Knowles is Remote Control’s project manager. Abigail Watson is a Research Officer with Remote Control. We would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to the many people who have given up time and shared their knowledge with us for this report. Some of them, often still in serving or official positions, have preferred to remain anonymous and are not named here. None of them bear responsibility for any of the opinions (or errors) in this report, which are the authors’ own. In alphabetical order: Dapo Akande, Richard Aldrich, Malcolm Chalmers, Lindsay Clarke, Chris Cole, Rory Cormac, Ian Davis, Joseph Devanny, Anthony Dworkin, Frank Foley, Ulrike Franke, Chris Fuller, Jennifer Gibson, Anthony Glees, Michael Goodman, Jim Killock, Ewan Lawson, Peter Lee, Elizabeth Minor, Jon Moran, Michael Pryce, Julian Richards, Peter Roberts, Paul Rogers, Javier Ruiz Diaz, Paul Schulte, Namir Shabibi, Adam Svendsen, Jack Watling, Nicholas Wheeler, and Chris Woods. We would also like to acknowledge the expertise that was shared with us by the Institute for Conflict, Cooperation and Security at the University of Birmingham and the University of Oxford, which has been truly invaluable. -

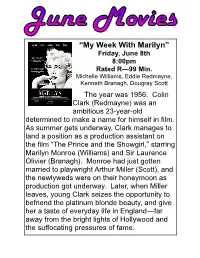

“My Week with Marilyn” Friday, June 8Th 8:00Pm Rated R—99 Min

“My Week With Marilyn” Friday, June 8th 8:00pm Rated R—99 Min. Michelle Williams, Eddie Redmayne, Kenneth Branagh, Dougray Scott The year was 1956. Colin Clark (Redmayne) was an ambitious 23-year-old determined to make a name for himself in film. As summer gets underway, Clark manages to land a position as a production assistant on the film “The Prince and the Showgirl,” starring Marilyn Monroe (Williams) and Sir Laurence Olivier (Branagh). Monroe had just gotten married to playwright Arthur Miller (Scott), and the newlyweds were on their honeymoon as production got underway. Later, when Miller leaves, young Clark seizes the opportunity to befriend the platinum blonde beauty, and give her a taste of everyday life in England—far away from the bright lights of Hollywood and the suffocating pressures of fame. Trailer park My Week with Marilyn: watch the trailer - video. Marilyn Monroe, in the UK to shoot The Prince and the Showgirl with Sir Laurence Olivier, befriends Colin Clark - an assistant on the film. Published: 16 Feb 2012. My Week with Marilyn: watch the trailer - video. January 2012. Baftas 2012 shortlist: 'It reflects the quality of films out this year' - video. Michelle Williams dazzles as Monroe in new film My Week With Marilyn – a film that celebrates the star's timeless off-duty style. Published: 15 Nov 2011. The magic of Marilyn Monroe. August 2011. My Week With Marilyn to premiere at New York film festival. Simon Curtis's film about encounter between Marilyn Monroe and UK assistant film director to screen as festival centrepiece.