Anusara Yoga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prescribing Yoga to Supplement and Support Psychotherapy

12350-11_CH10-rev.qxd 1/11/11 11:55 AM Page 251 10 PRESCRIBING YOGA TO SUPPLEMENT AND SUPPORT PSYCHOTHERAPY VINCENT G. VALENTE AND ANTONIO MAROTTA As the flame of light in a windless place remains tranquil and free from agitation, likewise, the heart of the seeker of Self-Consciousness, attuned in Yoga, remains free from restlessness and tranquil. —The Bhagavad Gita The philosophy of yoga has been used for millennia to experience, examine, and explain the intricacies of the mind and the essence of the human psyche. The sage Patanjali, who compiled and codified the yoga teachings up to his time (500–200 BCE) in his epic work Yoga Darsana, defined yoga as a method used to still the fluctuations of the mind to reach the central reality of the true self (Iyengar, 1966). Patanjali’s teachings encour- age an intentional lifestyle of moderation and harmony by offering guidelines that involve moral and ethical standards of living, postural and breathing exercises, and various meditative modalities all used to cultivate spiritual growth and the evolution of consciousness. In the modern era, the ancient yoga philosophy has been revitalized and applied to enrich the quality of everyday life and has more recently been applied as a therapeutic intervention to bring relief to those experiencing Copyright American Psychological Association. Not for further distribution. physical and mental afflictions. For example, empirical research has demon- strated the benefits of yogic interventions in the treatment of depression and anxiety (Khumar, Kaur, & Kaur, 1993; Shapiro et al., 2007; Vinod, Vinod, & Khire, 1991; Woolery, Myers, Sternlieb, & Zeltzer, 2004), schizophrenia (Duraiswamy, Thirthalli, Nagendra, & Gangadhar, 2007), and alcohol depen- dence (Raina, Chakraborty, Basit, Samarth, & Singh, 2001). -

—The History of Hatha Yoga in America: The

“The History of Hatha Yoga in America: the Americanization of Yoga” Book proposal By Ira Israel Although many American yoga teachers invoke the putative legitimacy of the legacy of yoga as a 5000 year old Indian practice, the core of the yoga in America – the “asanas,” or positions – is only around 600 years old. And yoga as a codified 90 minute ritual or sequence is at most only 120 years old. During the period of the Vedas 5000 years ago, yoga consisted of groups of men chanting to the gods around a fire. Thousands of years later during the period of the Upanishads, that ritual of generating heat (“tapas”) became internalized through concentrated breathing and contrary or bipolar positions e.g., reaching the torso upwards while grounding the lower body downwards. The History of Yoga in America is relatively brief yet very complex and in fact, I will argue that what has happened to yoga in America is tantamount to comparing Starbucks to French café life: I call it “The Americanization of Yoga.” For centuries America, the melting pot, has usurped sundry traditions from various cultures; however, there is something unique about the rise of the influence of yoga and Eastern philosophy in America that make it worth analyzing. There are a few main schools of hatha yoga that have evolved in America: Sivananda, Iyengar, Astanga, and later Bikram, Power, and Anusara (the Kundalini lineage will not be addressed in this book because so much has been written about it already). After practicing many of these different “styles” or schools of hatha yoga in New York, North Carolina, Florida, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and Paris as well as in Thailand and Indonesia, I became so fascinated by the history and evolution of yoga that I went to the University of California at Santa Barbara to get a Master of Arts Degree in Hinduism and Buddhism which I completed in 1999. -

Patanjali Yogsutra & Mantras

THE LITTLE MASTER OF YOGA -2021 (Curriculum for TGMY Yoga) THE POSTURES Basic Level Advance Level (Day-3) (Day-1) (Day-2) 1. Siddhasana 16. Vrikshasana 1. Dhanurasana 11. Shirshana 2. Swastikasan 17. Mandukasana 2. Paschimottanasana 12. Rajkapotsana 3. Padmasana 18. Vrishasana 3. Sankatasana 13. Purn 4. Bhadrasana, 19. Shalabhasana 4. Mayurasana Matsyendrasana 5. Muktasana 20. Makarasana 5. Kukkutasana 14. Tittibhasana 6. Vajrasana 21. Ushtrasana 6. Kurmasana 15. Kaundinyasana 7. Svastikasana, 22. Bhujangasana 7. Uttanakurmakasana 16. Astavakrasana 23. Yogasana 8. Uttanamandukasan 8. Simhasana 17. Eka Pada Free Hand 9. Gomukhasana 24. Utkatasana 9. Garudasana Chakrasana 10. Virasana, 25. Savasana 10. Chakrasan 18. Purn 11. Mritasana Dhanurasana 12. Guptasana 19. Yoganidrasana 13. Matsyasana 20. Vrischikasana 14. Matsyendrasana 15. Gorakshana PATANJALI YOGSUTRA & MANTRAS Understanding of Yoga according to Text Mantras & Prayers - Definition of Yoga in - 5 general benefits of Yoga - Aum Chanting Patanjali - 5 general benefits of Asana - Aum Sahana Bhavtu - Definition of Yoga in Gita - 5 general benefits of - Gayatri Mantra - Definition of Yoga in Vedas Pranayama THE LITTLE MASTER OF YOGA The Little Master of Yoga contest is a great way to celebrate true sense of Yoga among the children for their individual practices, learning, and understanding with the philosophy of Yoga. The Little Master of Yoga contest for children of 9 to 17 years age group. Each phase of contest is taking the Little Masters towards various aspects of yoga and motivating them through proper understanding and its amazing benefits of Yoga. While preparing himself for this contest, the contestants are also advised to go through some other available resources also such as Yoga Literature, YouTube clips, newspaper articles, magazines, Yoga sites, and ancient texts. -

Exploring the Healing Effects of Yoga for Trauma in Children and Youth: the Stories of Yoga Instructors

Exploring the Healing Effects of Yoga for Trauma in Children and Youth: The Stories of Yoga Instructors By: Sarah Bonnell BA, University of Victoria, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Child and Youth Care © Sarah Bonnell University of Victoria 2016 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Exploring the Healing Effects of Yoga for Trauma in Children and Youth: The Stories of Yoga Instructors By: Sarah Bonnell BA CYC, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Daniel Scott, School of Child and Youth Care Supervisor Dr. Marie Hoskins, School of Child and Youth Care Department Member iii Abstract Dr. Daniel Scott, School of Child and Youth Care Supervisor Dr. Marie Hoskins, School of Child and Youth Care Department Member Yoga as a therapeutic modality for treating trauma is currently emerging as an important topic of research with several new studies being produced to analyze its effectiveness on varying populations of traumatized individuals. Research is beginning to demonstrate that individuals who suffer the effects of trauma have often experienced several negative events that accumulate over the course of one’s lifetime. It has been displayed that when treated early, the adverse effects of trauma may be much less debilitating. Recent studies indicate traumatic memories are often stored within the body and are difficult to recall through cognition alone. Therefore, somatic therapies such as yoga are proving to be an effective means of working through this unresolved trauma. -

Notification Pgm-Cet-2014

No.DMER/PGM-CET 2014/Question Paper/Notification No.5/2-A, Date : 28/01/2014. NOTIFICATION PGM-CET-2014 The Common Entrance Test for Postgraduate Medical Courses, PGM-CET-2014 was conducted on Sunday, 5th January, 2014 by Competent Authority appointed by Government of Maharashtra. The provisional result of the same is being declared on 28th January 2014. The subject experts have opined that seven (07) questions in the question paper of the aforesaid examination are defective. The Competent Authority, on the basis of the opinion and advice of the respective subject expert has taken a decision to make these seven (07) questions "non-evaluative / invalid". These questions carried one mark each for a correct answer. Therefore instead of reducing the maximum number of marks from 300 to 293, The Competent Authority has decided to allot one mark each for these defective MCQ to all candidates who appeared in this examination, thus keeping maximum marks as 300; unchanged. The details of "Non-evaluative/ Invalid" MCQ are shown in the Table No. - 1 at respective Sr. No. in each version. Table No. – 1 – Version-wise Sr. No. of Non-evaluative/ Invalid Questions Sr. No. in Sr. No. in Sr. No. Sr. No. Sr. No. Version 11 Version 22 in Version 33 in Version 44 1 54 44 19 294 2 60 75 50 25 3 129 164 139 114 4 157 202 177 152 5 181 21 296 271 6 194 184 159 134 7 199 134 109 84 The subject expert also opined that there is change in Answer Key in Four (04) questions. -

Yoga Poses for Your Health

2013 Yoga Poses for Your Health Compiled by: Fitness-Health Team Fitness.com Yoga for Your Health Curious about yoga? Yoga is a very popular form of workout that more and more people are starting to get into as they learn about all the different benefits that it can provide. But, if you're brand new to yoga and haven't done your research, you may not be making the most of this type of workout program. There are a number of different variations of yoga that can be performed, so it's essential that you understand what each is about so that you can pick and choose the variety that is going to best benefit you with the goal set that you currently have. Learning some of the top key benefits that you'll get from each yoga class that you perform will also help you stay motivated and committed to doing your sessions and making the physical progress you desire. Yoga is about more than just physical activity however. Those who participate in yoga for an ongoing period of time are going to notice that they benefit from a psychological standpoint as well. While many other variations of exercise as strictly focused on burning fat, improving your strength, or allowing you to have some fun with your physical fitness program, yoga is one that really interconnects you mind and body together. So read through the following series of articles so that you can get all the vital information that you need to know about yoga. A Brief History Of Yoga - If you are considering taking up yoga, or you are new to the practice you might be curious to find out more about yoga’s fascinating history. -

INTERVIEW with B.K.S. IYENGAR on BACKBENDS 12/5/91 Questions Asked by Victor Oppenheimer and Patricia Walden

INTERVIEW WITH B.K.S. IYENGAR ON BACKBENDS 12/5/91 Questions asked by Victor Oppenheimer and Patricia Walden These questions were asked during the teachers’ backbend intensive Mr. Iyengar taught in November-December, 1991. This intensive was videotaped, and some of the questions refer to the videotapes. The interview was transcribed and edited by Francie Ricks. Victor Oppenheimer: Why backbends? B.K.S. Iyengar: In the asana systems, the most advanced postures are the backbends. The human structure is such that the idea does not strike anyone that the spinal vertebrae can be moved backward as well as forward and sideways, without causing injury. In the field of yoga, backbends are not taught at the early stages in the practice of this art, but only when the body is trained and when it is tuned and toned to such an extent that it can accept these poses. Backbends are to be felt more than expressed. The other postures can be expressed and then felt. But in backbends, like meditations, each person has to feel. And that’s why I thought that after fifty years of teaching, at least some of my students should get the background of the right means to perform the backbends. Backbends are not poses meant for exhibitionism. Backbends are meant to understand the back parts of our bodies. The front body can be seen with the eyes. The back body cannot be seen; it can only be felt. That’s why I say these are the most advanced postures, where the mind begins to look at the back, first on the peripheral level, then inwards, towards the core. -

Reduced Size Daily Practice Guide

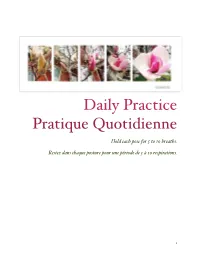

Daily Practice Pratique Quotidienne Hold each pose for 5 to 10 breaths. Restez dans chaque posture pour une période de 5 à 10 respirations. !1 VIRASANA hero pose/ Pose du héros close your eyes, listen to your breath fermez vos yeux, écoutez votre respiration !2 BALASANA child’s pose/ posture de l’enfant - big toes touching - gros orteils ensemble - knees as wide as your ribcage - genoux écartés à largeur du torse - arms overhead, straight with elbows - bras au dessus de la tête, droits et les o# the ground coudes surélevés !3 TABLE table pose / posture de la table - hands aligned with shoulders - mains alignées avec les épaules - knees aligned with hips - genoux alignés avec les hanches - fingers spread, collarbones wide - doigts séparés, clavicules écartées - lower ribs uplifted - cage thoracique levée !4 ADHO MUKHA SHVANASANA downward dog pose / posture du chien face vers le bas - arms and hands outer shoulder-width - bras et mains écartés à largeur des apart, broad collarbones épaules - inner and outer edges of hands rooted - côtés intérieurs et extérieurs des mains et bouts des doigts ancrés - legs hip-width apart, thighs back - jambes écartées à largeur des hanches, - feet parallel cuisses reculées gentle version: knees on ground - pieds parallèles version douce: genoux au sol !5 UTTANASANA deep forward bend / étirement intense vers l’avant - feet parallel - pieds parallèles - knees straight forward, thighs back - genoux face à l’avant, cuisses reculées - hands on ground or blocks by pinky - mains ou doigts au sol ou sur des blocs toe à côté des petits orteils moderate version: legs hip-width apart version moderée: jambes écartées à largeur des hanches. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

8 Core Strengthening Moves with the Yoga Wheel

8 Core Strengthening Moves with the Yoga Wheel Got a yoga wheel? Looking for ways to use it, instead of letting it accumulate dust in your prop corner? I was guilty of this until I took my first yoga wheel workshop and got comfortable playing around with it, and now I use my wheel for a lot more than just draping myself over top in a yummy backbend (which IS really nice, I’m not gonna lie). But, there are TONS of other ways to use your yoga wheel, and it’s super fun to get creative. This accumulation of poses focuses on strength building through the center of the body. Yes, the core. There, I said it. I almost hate to use the word “core” because I feel like it’s so fitness-based and overused. But….I do think core strength is actually really important to overall strength and staying out of pain. As I’ve entered my 40s, my low back pays the price if I neglect good-old-fashioned core work, as I’ll collapse into my lumbar curve. Also, I am a bit obsessed with arm balances and inversions, and core work is KEY to developing the strength to tackle these postures. When I practice these, I feel strong, free, and balanced…like I can take on the world. I hope these yoga wheel moves help you feel the same way! If you don’t have a wheel yet, I prefer the original Dharma Yoga Wheel, which you can get here. (Just FYI, this is an affiliate link, which means if you make a purchase using the link I may receive some love in return!) Without further ado, below are 8 postures using your yoga wheel to strengthen your core (and more). -

TEACHING HATHA YOGA Teaching Hatha Yoga

TEACHING HATHA YOGA Teaching Hatha Yoga ii Teaching Hatha Yoga TEACHING HATHA YOGA ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Daniel Clement with Naomi Clement Illustrations by Naomi Clement 2007 – Open Source Yoga – Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada iii Teaching Hatha Yoga Copyright © 2007 Daniel Clement All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written consent of the copyright owner, except for brief reviews. First printing October 2007, second printing 2008, third printing 2009, fourth printing 2010, fifth printing 2011. Contact the publisher on the web at www.opensourceyoga.ca ISBN: 978-0-9735820-9-3 iv Teaching Hatha Yoga Table of Contents · Preface: My Story................................................................................................viii · Acknowledgments...................................................................................................ix · About This Manual.................................................................................................ix · About Owning Yoga................................................................................................xi · Reading/Resources................................................................................................xii PHILOSOPHY, LIFESTYLE & ETHICS.........................................................................xiii -

Ajna Vishuddhi Anahata Manipura Swadhisthana Moo I Ad Hara

Ajna Vishuddhi Anahata Manipura Swadhisthana Moo I adhara Chapter 7 : Chakras Chakras The invisible yet powerful core centers of consciousness, eager to receive prana in abundance The scriptures describing the chakras belong uniquely to Indian Tantra. Chakras are invisible core centers of the different planes of psychic consciousness and lie along the sushumna in the spinal column. The chakras whirl and radiate, when prana, the vibrating life force, freely flows through them, and takes on the form of a vortex of energy Before we can come to a better understanding of chakras, we need to look at the body from its subtle levels first. From time immemorial yogis and other great spiritual practitioners discovered through direct experience that the body consists of five different sheaths or divides, knows as koshas. These sheaths or divides, as previously mentioned, are seen as different dimensions of energy substances, from the subtle to the gross. Each kosha is permeated with prana. The gross visible sheat is the physical body. The four invisible sheaths, two astral and two causal in nature, are together often referred to as the subtle body. The five koshas coexist together. They protect each other against premature breakthroughs, meaning psychological or spiritual breakthroughs that are not yet desirable. In the physical body lies the visible nervous system. In the astral body, formed by the pranic and mental koshas lies the invisible system of energy channels and centers of consciousness known as nadis and chakras. This system cannot be seen through the naked eye. Chakra is often translated as wheel, which refers to a circular object or formation.