Ultimate Guide to Yoga for Healing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rooted Elements a Kinesthetic Approach Connecting Our Children to Their Nnei R and Outer World Alisha Meyer the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 2012 Rooted Elements A Kinesthetic Approach Connecting Our Children to Their nneI r and Outer World Alisha Meyer The University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Recommended Citation Meyer, Alisha, "Rooted Elements A Kinesthetic Approach Connecting Our Children to Their nneI r and Outer World" (2012). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1385. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1385 This Professional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROOTED ELEMENTS A KINESTHETIC APPROACH CONNECTING OUR CHILDREN TO THEIR INNER AND OUTER WORLD By ALISHA BRIANNE MEYER BA Elementary Education, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 2003 Professional Paper presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Fine Arts, Integrated Arts and Education The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2012 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Associate Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Karen Kaufmann, Chair Fine Arts Jillian Campana, Committee Member Fine Arts Rick Hughes, Committee Member Fine Arts © COPYRIGHT by Alisha Brianne Meyer 2012 All Rights Reserved ii Meyer, Alisha, M.A., May 2012 Integrating Arts into Education Rooted Elements Chairperson: Karen Kaufmann Rooted Elements is a thematic naturalistic guide for classroom teachers to design engaging lessons focused in the earth elements. -

Prescribing Yoga to Supplement and Support Psychotherapy

12350-11_CH10-rev.qxd 1/11/11 11:55 AM Page 251 10 PRESCRIBING YOGA TO SUPPLEMENT AND SUPPORT PSYCHOTHERAPY VINCENT G. VALENTE AND ANTONIO MAROTTA As the flame of light in a windless place remains tranquil and free from agitation, likewise, the heart of the seeker of Self-Consciousness, attuned in Yoga, remains free from restlessness and tranquil. —The Bhagavad Gita The philosophy of yoga has been used for millennia to experience, examine, and explain the intricacies of the mind and the essence of the human psyche. The sage Patanjali, who compiled and codified the yoga teachings up to his time (500–200 BCE) in his epic work Yoga Darsana, defined yoga as a method used to still the fluctuations of the mind to reach the central reality of the true self (Iyengar, 1966). Patanjali’s teachings encour- age an intentional lifestyle of moderation and harmony by offering guidelines that involve moral and ethical standards of living, postural and breathing exercises, and various meditative modalities all used to cultivate spiritual growth and the evolution of consciousness. In the modern era, the ancient yoga philosophy has been revitalized and applied to enrich the quality of everyday life and has more recently been applied as a therapeutic intervention to bring relief to those experiencing Copyright American Psychological Association. Not for further distribution. physical and mental afflictions. For example, empirical research has demon- strated the benefits of yogic interventions in the treatment of depression and anxiety (Khumar, Kaur, & Kaur, 1993; Shapiro et al., 2007; Vinod, Vinod, & Khire, 1991; Woolery, Myers, Sternlieb, & Zeltzer, 2004), schizophrenia (Duraiswamy, Thirthalli, Nagendra, & Gangadhar, 2007), and alcohol depen- dence (Raina, Chakraborty, Basit, Samarth, & Singh, 2001). -

Externally Rotated Standing Poses D2

Practice: Externally Rotated Standing Poses D2 Length of Lesson ● 90-120 min Materials ● Mats ● Props (blocks) ● Wall Learning Objectives ● To instruct and clarify the Universal Actions in externally rotated standing poses ● To clearly differentiate standing poses that are neutral in the hip versus poses that are externally rotated in the hip ● To teach the dual actions in an externally rotated pose ● Students will understand that the standing thigh is the thigh that is externally rotated in ardha chandrasana Assessment ● Through participation Practice Notes ● Peak: Ardha Chandrasana ● Emphasize the difference between poses that are working towards neutral the hip and poses that are working one of the legs in external rotation. ● Have students deeply work external rotation in each of these poses. ● Each externally rotated pose should reinforce the external action of the front hip. ● In each pose, teach the Universal Actions - particularly the Universal Paired Actions - in order to help students recognize them in a variety of positions. ● Reinforce the Diagonal Paired Actions in the externally rotated poses. Universal Simple Actions ● Root through the four corners of your feet ● Lengthen through the four sides of your waist ● Lengthen through the crown of your head ● Engage your core ● Spread your chest ● Soften your face © Rachel Scott 2018 1 ● Breath cueing Universal Paired Actions Feet ● Lift your inner arches up ● Hug your outer ankles in Pelvis ● Press the top of your thighs back (creates anterior pelvic tilt) ● Lengthen your sitting -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

Exploring the Healing Effects of Yoga for Trauma in Children and Youth: the Stories of Yoga Instructors

Exploring the Healing Effects of Yoga for Trauma in Children and Youth: The Stories of Yoga Instructors By: Sarah Bonnell BA, University of Victoria, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Child and Youth Care © Sarah Bonnell University of Victoria 2016 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Exploring the Healing Effects of Yoga for Trauma in Children and Youth: The Stories of Yoga Instructors By: Sarah Bonnell BA CYC, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Daniel Scott, School of Child and Youth Care Supervisor Dr. Marie Hoskins, School of Child and Youth Care Department Member iii Abstract Dr. Daniel Scott, School of Child and Youth Care Supervisor Dr. Marie Hoskins, School of Child and Youth Care Department Member Yoga as a therapeutic modality for treating trauma is currently emerging as an important topic of research with several new studies being produced to analyze its effectiveness on varying populations of traumatized individuals. Research is beginning to demonstrate that individuals who suffer the effects of trauma have often experienced several negative events that accumulate over the course of one’s lifetime. It has been displayed that when treated early, the adverse effects of trauma may be much less debilitating. Recent studies indicate traumatic memories are often stored within the body and are difficult to recall through cognition alone. Therefore, somatic therapies such as yoga are proving to be an effective means of working through this unresolved trauma. -

Level 1 Asanas

LEVEL 1 ASANAS Standing Poses Tadasana (Mountain Pose) Vrksasana (Tree Pose) Virabhadrasana II (Warrior Pose 2) Utthita Parsvakonasana (Extended Lateral Flank Stretch) Utthita Trikonasana (Extended Triangle Pose) Virabhadrasasana (Warrior Pose 1) Uttanasana (Standing Forward Bend) Prasarita Padottanasana (Extended Leg Stretch) Parsvottanasana (Intense Side Stretch) Seated Poses Vajasana (Thunderbolt Pose) Virasana (Hero Pose) Sukhasana (Comfortable Seated Pose) Dandasana (Staff Pose) Upavista Konasana (Seated Angle Pose) Baddha Konasana (Bound Angle Pose) Forward Bends Paschimottanasa (Intense Seated Back Stretch) Supta Padangusthasana (Reclining Leg Stretch) Twists Sukhasana Twist (Easy Cross Leg Twists) Bharadvasjasana (Chair Twist) Bharadvasjasana I (Seated Twist) Jathara Parivartanasana ( Supine Adominal Twists) Crocodile Twists Maricyasana III LEVEL 1 ASANAS Hip Openers Supta Padangusthasana II (Reclining Leg Stretch 2) Judith’s Hip Opener Gomukhasana (Face of the Cow Pose) Arm Work Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward Facing Dog Pose) Plank Pose Chaturanga Dandasana (Four Point Staff Pose) Half Handstand Simple Backbends Passive Chest Opener (Lie over a rolled up blanket) Setu Bandha Sarvangasana (Bridge Pose) Ustrasana (Camel Pose) Restorative Poses Supported Uttanasana (Forward bend with head on block - or buttocks on wall) Supported Adho Mukha Svanesana (Dog Pose with head support) Supported Setu Bandha Sarvangasana (Bridge Pose with block under sacrum) Supta Virasana (Reclining Bound Pose) Supta Baddha Konasana (Reclining Bound Angle Pose) Viparita Karani (Two blankets under hips- legs up wall) Savasana (Corpse Pose). -

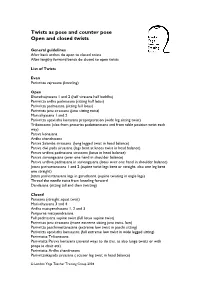

Twists As Pose & Counter Pose

Twists as pose and counter pose Open and closed twists General guidelines After back arches do open to closed twists After lengthy forward bends do closed to open twists List of Twists Even Parivritta vajrasana (kneeling) Open Bharadvajrasana 1 and 2 (half virasana half baddha) Parivritta ardha padmasana (sitting half lotus) Parivritta padmasana (sitting full lotus) Parivritta janu sirsasana (janu sitting twist) Marischyasana 1 and 2 Parivritta upavistha konasana prepreparation (wide leg sitting twist) Trikonasana (also from prasarita padottanasana and from table position twist each way) Parsva konasana Ardha chandrasana Parsva Salamba sirsasana (long legged twist in head balance) Parsva dwi pada sirsasana (legs bent at knees twist in head balance) Parsva urdhva padmasana sirsasana (lotus in head balance) Parsva sarvangasana (over one hand in shoulder balance) Parsva urdhva padmasana in sarvangasana (lotus over one hand in shoulder balance) Jatara parivartanasana 1 and 2 (supine twist legs bent or straight, also one leg bent one straight) Jatara parivartanasana legs in garudasana (supine twisting in eagle legs) Thread the needle twist from kneeling forward Dandasana (sitting tall and then twisting) Closed Pasasana (straight squat twist) Marischyasana 3 and 4 Ardha matsyendrasana 1, 2 and 3 Paripurna matsyendrasana Full padmasana supine twist (full lotus supine twist) Parivritta janu sirsasana (more extreme sitting janu twist, low) Parivritta paschimottanasana (extreme low twist in paschi sitting) Parivritta upavistha konsasana (full extreme -

INTERVIEW with B.K.S. IYENGAR on BACKBENDS 12/5/91 Questions Asked by Victor Oppenheimer and Patricia Walden

INTERVIEW WITH B.K.S. IYENGAR ON BACKBENDS 12/5/91 Questions asked by Victor Oppenheimer and Patricia Walden These questions were asked during the teachers’ backbend intensive Mr. Iyengar taught in November-December, 1991. This intensive was videotaped, and some of the questions refer to the videotapes. The interview was transcribed and edited by Francie Ricks. Victor Oppenheimer: Why backbends? B.K.S. Iyengar: In the asana systems, the most advanced postures are the backbends. The human structure is such that the idea does not strike anyone that the spinal vertebrae can be moved backward as well as forward and sideways, without causing injury. In the field of yoga, backbends are not taught at the early stages in the practice of this art, but only when the body is trained and when it is tuned and toned to such an extent that it can accept these poses. Backbends are to be felt more than expressed. The other postures can be expressed and then felt. But in backbends, like meditations, each person has to feel. And that’s why I thought that after fifty years of teaching, at least some of my students should get the background of the right means to perform the backbends. Backbends are not poses meant for exhibitionism. Backbends are meant to understand the back parts of our bodies. The front body can be seen with the eyes. The back body cannot be seen; it can only be felt. That’s why I say these are the most advanced postures, where the mind begins to look at the back, first on the peripheral level, then inwards, towards the core. -

A Health Style Zine

Pyourist A Health Style Zine Because Your Body is OUR Business October 2019 KEEP AN EYE OUT... Table of Contents 2... Keep An Eye Out... 3-4... 10 Benefits of Pilates Exercise by Marguerite Ogle 5-6... Fight Pesky Colds With Regular Chiropractic Care & The Benefits of Chiropractic for Sinusitis OVER AT CORE OVER AT POUR by Dr. Anthony Lauro 7-8... 10 Ways to Keep Your Fascia Healthy so Your Body Moves Pain-Free by Gabrielle Kassel 2nd location is open! Open Daily 7:30am-3pm! 9-10... The Fitness Benefits of Jumping by Cathe Friedrich PYOUR CORE LITTLE SILVER Pyour Pour Little Silver Juices, Smoothies, Espresso & 11-12... 7 Ways Aerial Yoga Will take Your Workout to the Next Level by Caitlin Carlson Ca 38 Church St Small Bites Little Silver, NJ 07739 732-758-9200 38 Church St 13-14... Intuitive & Mindful Eating by Jessica Lacontrain Carlson Follow us! Little Silver, NJ 07739 732-758-8500 15-16... The Science on Soy by Monica Reinagel Instagram: @pyourcorels Facebook: PYOUR CORE LS 17-18... Food Made Simple Open Seasonally in Surf City 616 Long Beach Blvd Open Year round in surf city! Surf City, NJ 08008 19... Introducing Our Newest Trainer & Class pyour core surf city 609-494-pour 604 Long Beach Blvd Surf City, NJ 08008 20... Thoughts from a Pyourist In-house Sunday Sampler! Follow Us! 609-494-3500 Join us in Little Silver 21... References Intagram: @PyourPour Instagram: @pyourcore October 27, 2019 Facebook: Pyour Pour Facebook: Pyour Core for our Prizes, giveaways, & much more 2 10 Benefits of Pilates Exercise Continued “10 Benefits of Pilates Exercise” by Marguerite Ogle 6. -

TRAINING the YOUNG ACTOR: a PHYSICAL APPROACH a Thesis

TRAINING THE YOUNG ACTOR: A PHYSICAL APPROACH A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Anthony Lewis Johnson December, 2009 TRAINING THE YOUNG ACTOR: A PHYSICAL APPROACH Anthony Lewis Johnson Thesis Approved: Accepted: __________________________ __________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Mr. James Slowiak Dr. Dudley Turner __________________________ __________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Durand Pope Dr. George R. Newkome __________________________ __________________________ School Director Date Mr. Neil Sapienza ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION TO TRAINING THE YOUNG ACTOR: A PHYSICAL APPROACH...............................................................................1 II. AMERICAN INTERPRETATIONS OF STANISLAVSKI’S EARLY WORK .......5 Lee Strasberg .............................................................................................7 Stella Adler..................................................................................................8 Robert Lewis...............................................................................................9 Sanford Meisner .......................................................................................10 Uta Hagen.................................................................................................11 III. STANISLAVSKI’S LATER WORK .................................................................13 Tension -

8 Core Strengthening Moves with the Yoga Wheel

8 Core Strengthening Moves with the Yoga Wheel Got a yoga wheel? Looking for ways to use it, instead of letting it accumulate dust in your prop corner? I was guilty of this until I took my first yoga wheel workshop and got comfortable playing around with it, and now I use my wheel for a lot more than just draping myself over top in a yummy backbend (which IS really nice, I’m not gonna lie). But, there are TONS of other ways to use your yoga wheel, and it’s super fun to get creative. This accumulation of poses focuses on strength building through the center of the body. Yes, the core. There, I said it. I almost hate to use the word “core” because I feel like it’s so fitness-based and overused. But….I do think core strength is actually really important to overall strength and staying out of pain. As I’ve entered my 40s, my low back pays the price if I neglect good-old-fashioned core work, as I’ll collapse into my lumbar curve. Also, I am a bit obsessed with arm balances and inversions, and core work is KEY to developing the strength to tackle these postures. When I practice these, I feel strong, free, and balanced…like I can take on the world. I hope these yoga wheel moves help you feel the same way! If you don’t have a wheel yet, I prefer the original Dharma Yoga Wheel, which you can get here. (Just FYI, this is an affiliate link, which means if you make a purchase using the link I may receive some love in return!) Without further ado, below are 8 postures using your yoga wheel to strengthen your core (and more). -

TEACHING HATHA YOGA Teaching Hatha Yoga

TEACHING HATHA YOGA Teaching Hatha Yoga ii Teaching Hatha Yoga TEACHING HATHA YOGA ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Daniel Clement with Naomi Clement Illustrations by Naomi Clement 2007 – Open Source Yoga – Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada iii Teaching Hatha Yoga Copyright © 2007 Daniel Clement All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written consent of the copyright owner, except for brief reviews. First printing October 2007, second printing 2008, third printing 2009, fourth printing 2010, fifth printing 2011. Contact the publisher on the web at www.opensourceyoga.ca ISBN: 978-0-9735820-9-3 iv Teaching Hatha Yoga Table of Contents · Preface: My Story................................................................................................viii · Acknowledgments...................................................................................................ix · About This Manual.................................................................................................ix · About Owning Yoga................................................................................................xi · Reading/Resources................................................................................................xii PHILOSOPHY, LIFESTYLE & ETHICS.........................................................................xiii