Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RABBINIC KNOWLEDGE of BLACK AFRICA (Sifre Deut. 320)

1 [The following essay was published in the Jewish Studies Quarterly 5 (1998) 318-28. The essay appears here substantially as published but with some additions indicated in this color .]. RABBINIC KNOWLEDGE OF BLACK AFRICA (Sifre Deut. 320) David M. Goldenberg While the biblical corpus contains references to the people and practices of black Africa (e.g. Isa 18:1-2), little such information is found in the rabbinic corpus. To a degree this may be due to the different genre of literature represented by the rabbinic texts. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that black Africa and its peoples would be entirely unknown to the Palestinian Rabbis of the early centuries. An indication of such knowledge is, I believe, found imbedded in a midrashic text of the third century. Deut 32:21 describes the punishment God has decided to inflict on Israel for her disloyalty to him: “I will incense them with a no-folk ( be-lo < >am ); I will vex them with a nation of fools ( be-goy nabal ).” A tannaitic commentary to the verse states: ואני אקניאם בלא עם : אל תהי קורא בלא עם אלא בלוי עם אלו הבאים מתוך האומות ומלכיות ומוציאים אותם מתוך בתיהם דבר אחר אלו הבאים מברבריא וממרטניא ומהלכים ערומים בשוק “And I will incense them with a be-lo < >am .” Do not read bl < >m, but blwy >m, this refers to those who come from among the nations and kingdoms and expel them [the Jews] from their homes. Another interpretation: This refers to those who come from barbaria and mr ãny <, who go about naked in the market place. -

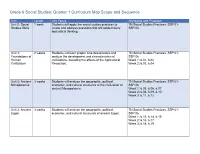

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence Unit Length Unit Focus Standards and Practices Unit 0: Social 1 week Students will apply the social studies practices to TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Studies Skills create and address questions that will guide inquiry SSP.06 and critical thinking. Unit 1: 2 weeks Students will learn proper time designations and TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Foundations of analyze the development and characteristics of SSP.06 Human civilizations, including the effects of the Agricultural Week 1: 6.01, 6.02 Civilization Revolution. Week 2: 6.03, 6.04 Unit 2: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Mesopotamia economic, and cultural structures of the civilization of SSP.06 ancient Mesopotamia. Week 1: 6.05, 6.06, 6.07 Week 2: 6.08, 6.09, 6.10 Week 3: 6.11, 6.12 Unit 3: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Egypt economic, and cultural structures of ancient Egypt. SSP.06 Week 1: 6.13, 6.14, 6.15 Week 2: 6.16, 6.17 Week 3: 6.18, 6.19 Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Map Instructional Framework Course Description: World History and Geography: Early Civilizations Through the Fall of the Western Roman Empire Sixth grade students will study the beginnings of early civilizations through the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Students will analyze the cultural, economic, geographical, historical, and political foundations for early civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel, India, China, Greece, and Rome. -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

Nubian Scenes of Protection from Faras As an Aid to Dating 44 STEFAN JAKOBIELSKI

CENTRE D’ARCHÉOLOGIE MÉDITERRANÉENNE DE L’ACADÉMIE POLONAISE DES SCIENCES ÉTUDES et TRAVAUX XXI 2007 STEFAN JAKOBIELSKI Nubian Scenes of Protection from Faras as an Aid to Dating 44 STEFAN JAKOBIELSKI A feature which is characteristic only of Nubian art (and which evolved typologically in specifi c periods) is the manner of depicting local dignitaries protected by holy fi gures,1 which apart of its iconographic and historic values, can be used as an aid to dating. Of great assistance here is the known sequence of bishops of Pachoras,2 which allows the individual schemes to be sorted in chronological order. Although this type of representation had its precursors both in Coptic and early Byzantine designs,3 in Christian art it was only in Nubia that it endured and became a particularly popular theme of murals from the ninth century up to the Terminal Christian Period. Scenes depicting Nubian dignitaries pro- tected by holy fi gures do not feature in Faras Cathedral’s original eight century mural programme. The oldest known representation associated with this atelier comes from Abdalla-n Irqi4 and appears most closely related in terms of technique to Faras murals representing archangels (Michael – Field Inv. No. 1155 and in the one of scene of Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace – Field Inv. No. a80).6 It depicts an archangel with his right 1 The fi rst attempt at establishing a typology of these representations (see: M. DE GROOTH, Mögliche Ein- fl üsse auf die nubische Protektionsgebärde, in: N. JANSMA and M. DE GROOTH, Zwei Beiträge zur Ikonographie der nubischen Kunst, pp. -

A Note Towards Quantifying the Medieval Nubian Diaspora

23 A Note towards Quantifying the Medieval Nubian Diaspora Adam Simmons Throughout the Christian medieval period of the kingdoms of Nu- bia (c. sixth–fifteenth centuries), ideas, goods, and peoples traversed vast distances. Judging from primarily external sources, the Nubian diaspora has seldom been thought of as vast, whether in number or geographical scope, both in terms of the relocated and a non- permanently domiciled diaspora. Prior to the Christianisation of the kingdoms of Nobadia, Makuria, and Alwa in the sixth century, likely Nubian delegations, consisting of “Ethiopes,” were received in both Rome and Constantinople alongside ones from neighbouring peoples, such as the Blemmyes and Aksumites. Yet, medieval Nubia is more often seen as inclusive rather than diasporic. This brief dis- cussion will further show that Nubians were an interactive society within the wider Mediterranean, a topic most commonly seen in the debate on Nubian trade.1 Above all, it argues that Nubians had a long relationship with Mediterranean societies that has primarily been overlooked in scholarship. Whilst the evidence presented here is not aimed to be definitive, it does highlight that Nubia’s Mediterranean connections may even have been more diverse than what Giovan- ni Ruffini argued for in his book Medieval Nubia whilst describing Nubia as a “Mediterranean society in Africa.”2 May we even argue for a more developed thesis of interaction? What about the Nubian societies throughout the Mediterranean who interacted with other communities both spiritually and financially? It will be argued here that these questions should be revisited and have potential to fur- ther expand Ruffini’s Mediterranean thesis. -

A Brief Description of the Nobiin Language and History by Nubantood Khalil, (Nubian Language Society)

A brief description of the Nobiin language and history By Nubantood Khalil, (Nubian Language Society) Nobiin language Nobiin (also called Mahas-Fadichcha) is a Nile-Nubian language (North Eastern Sudanic, Nilo-Saharan) descendent from Old Nubian, spoken along the Nile in northern Sudan and southern Egypt and by thousands of refugees in Europe and the US. Nobiin is classified as a member of the Nubian language family along with Kenzi/Dongolese in upper Nubia, Meidob in North Darfur, Birgid in Central and South Darfur, and the Hill Nubian languages in Southern Kordofan. Figure 1. The Nubian Family (Bechhaus 2011:15) Central Nubian Western Northern Nubian Nubian ▪ Nobiin ▪ Meidob ▪ Old Nubian Birgid Hill Nubians Kenzi/ Donglese In the 1960's, large numbers of Nobiin speakers were forcibly displaced away from their historical land by the Nile Rivers in both Egypt and Sudan due to the construction of the High Dam near Aswan. Prior to that forcible displacement, Nobiin was primarily spoken in the region between the first cataract of the Nile in southern Egypt, to Kerma, in the north of Sudan. The following map of southern Egypt and Sudan encompasses the areas in which Nobiin speakers have historically resided (from Thelwall & Schadeberg, 1983: 228). Nubia Nubia is the land of the ancient African civilization. It is located in southern Egypt along the Nile River banks and extends into the land that is known as “Sudan”. The region Nubia had experienced writing since a long time ago. During the ancient period of the Kingdoms of Kush, 1 | P a g e the Kushite/Nubians used the hieroglyphic writing system. -

Grids and Datumsâšrepublic of Sudan

REPUBLIC OF rchaeological excavation of sites on the Nile above Aswan has confirmed human “Ahabitation in the river valley during the Paleolithic period that spanned more than 60,000 years of Sudanese history. By the eighth millennium B.C., people of a Neolithic culture had settled into a sedentary way of life there in fortified mud-brick villages, where they supplemented hunting and fishing on the Nile with grain gathering and cattle herding. Contact with Egypt probably occurred at a formative stage in the culture’s development because of the steady movement of population along the Nile River. Skeletal remains suggest a blending of negroid and Mediterranean populations during the Neolithic period (eighth to third millenia B.C.) that has remained relatively stable until theDelivered present, by Ingenta despite gradual infiltrationIP: 192.168.39.211by other elements. On: Sat, 25 Sep 2021 12:42:54 Copyright: American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing Northern Sudan’s earliest historical record comes from Egyptian sources, which described the land upstream from the first cataract, called Cush, as “wretched.” For more than 2,000 years after the Old kingdom emerged at Karmah, near present-day Dunqulah. After Egyptian power revived during the New Kingdom (ca. Kingdom (ca. 2700-2180 B.C.), Egyptian political 1570-1100 B.C.), the pharaoh Ahmose I incorporated Cush and economic activities determined the course as an Egyptian province governed by a viceroy. Although of the central Nile region’s history. Even during Egypt’s administrative control of Cush extended only down to intermediate periods when Egyptian political power the fourth cataract, Egyptian sources list tributary districts in Cush waned, Egypt exerted a profound cultural reaching to the Red Sea and upstream to the confluence of the and religious influence on the Cushite people. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521001358 - Reversing Sail: A History of the African Diaspora Michael A. Gomez Excerpt More information Introduction The dawn of the twenty-first century finds persons of varying ethnic and racial and religious backgrounds living together in societies all over the globe. The United Kingdom and France in Europe, together with the United States and Brazil in the Americas, are perhaps only the better known of many such societies, a principal dynamic of which concerns how groups maintain their identities while forming new and viable communities with those who do not share their backgrounds or beliefs. To achieve the latter requires a willingness on the part of all to learn about the histories and cultures of everyone in the society. This book is about people of African descent who found (and find) themselves living either outside of the African continent or in parts of Africa that were territorially quite distant from their lands of birth. It is a history of their experiences, contributions, victories, and struggles, and it is primarily concerned with massive movements and extensive relocations, over long periods of time, resulting in the dispersal of Africans and their descendants throughout much of the world. This phenomenon is referred to as the African Diaspora. Redistributions of European and Asian populations have also marked history, but the African Diaspora is unique in its formation. It is a story, or a collection of stories, like no other. As an undergraduate text, this book is written at a time of con- siderable perplexity, ambiguity, and seeming contradiction. People of African descent, or black people, can be found in all walks of life. -

Two Private Prayers in Wall Inscriptions in the Faras Cathedral

Études et Travaux XXX (2017), 303–314 Two Private Prayers in Wall Inscriptions in the Faras Cathedral A Ł, G O Abstract: The present paper aims at analysing two inscriptions from the Faras Cathedral. Both contain prayers addressed to God by certain individuals. The fi rst of them is in Greek and is modelled on Ps. 85:1–2; the second is an original composition in Old Nubian with information about the protagonist and the author in Greek. The publication gives the descrip- tion of inscriptions, transcript of texts with critical apparatus, translation, and commentary elucidating all signifi cant aspects of the texts. Keywords: Christian Nubia, Faras, wall inscriptions, Greek in Christian Nubia, Old Nubian, Biblical citations Adam Łajtar, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Warszawa; [email protected] Grzegorz Ochała, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Warszawa; [email protected] The present article has come into existence in connection with our work on a catalogue of wall inscriptions in the Faras cathedral.1 It off ers the publication of two inscriptions, which, although they diff er from one another in many respects (a diff erent location within the sacral space, a diff erent technique of execution, and a diff erent language), belong to the same genre of texts, namely prayers addressed to God by individuals. A typical private prayer put into an epigraphic text in Christian Nubia consists of two elements: (1) an invocation of God or a saint, and (2) a request for a favour made in the name of a person. The inscriptions studied here follow this general model but develop it in a diff erent way with respect to both the form and the contents. -

The Kingdom of Kush

Age of Empires Kush/ Nubia was an African Kingdom located to the south of Egypt Their close relationship with Egypt is evident on walls of Egyptian tombs and temples Next to Egypt, Kush was the greatest ancient civilization in Africa Kush was known for its rich gold mines Nub = gold in Egyptians Important trading hub Egyptian goods = grain, beer, linen Kush goods = gold, ivory, leather, timber Egypt often raided Kush and took control of parts of its territory Kush paid tribute to the pharaoh While under Egypt’s control, Kush became “Egyptianized” Kushites spoke Egyptian Worshipped same gods/goddesses Hired into the Egyptian Army Kush royal family was educated in Egypt After the collapse of the New Kingdom, there was a serious of weak and ineffective rulers causing Egypt to become extremely weak 730 B.C.E. Kush invaded and Egypt surrendered to King Piye Piye declared himself Pharaoh and “Uniter, of the Two Lands” Kushite pharaohs ruled Egypt for over 100 years Did not destroy Egyptian culture, but adapted Kushites were driven out by the Assyrians Meroe was safe out of Egypt's reach since they destroyed Napata (their previous capital) Important center of trade Production of iron Broke away from Egyptian tradition Had female leadership= kandakes or queen mothers Worshiped an African Lion god instead of Egyptian gods Story of Nubia www.youtube.com This short documentary tells the story of Nubia and the civilization that flourished in the Nile Valley for thousands of years and particularly between 800 BC and 400 .... -

Kush Under the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (C. 760-656 Bc)

CHAPTER FOUR KUSH UNDER THE TWENTY-FIFTH DYNASTY (C. 760-656 BC) "(And from that time on) the southerners have been sailing northwards, the northerners southwards, to the place where His Majesty is, with every good thing of South-land and every kind of provision of North-land." 1 1. THE SOURCES 1.1. Textual evidence The names of Alara's (see Ch. 111.4.1) successor on the throne of the united kingdom of Kush, Kashta, and of Alara's and Kashta's descen dants (cf. Appendix) Piye,2 Shabaqo, Shebitqo, Taharqo,3 and Tan wetamani are recorded in Ancient History as kings of Egypt and the c. one century of their reign in Egypt is referred to as the period of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.4 While the political and cultural history of Kush 1 DS ofTanwetamani, lines 4lf. (c. 664 BC), FHNI No. 29, trans!. R.H. Pierce. 2 In earlier literature: Piankhy; occasionally: Py. For the reading of the Kushite name as Piye: Priese 1968 24f. The name written as Pyl: W. Spiegelberg: Aus der Geschichte vom Zauberer Ne-nefer-ke-Sokar, Demotischer Papyrus Berlin 13640. in: Studies Presented to F.Ll. Griffith. London 1932 I 71-180 (Ptolemaic). 3 In this book the writing of the names Shabaqo, Shebitqo, and Taharqo (instead of the conventional Shabaka, Shebitku, Taharka/Taharqa) follows the theoretical recon struction of the Kushite name forms, cf. Priese 1978. 4 The Dynasty may also be termed "Nubian", "Ethiopian", or "Kushite". O'Connor 1983 184; Kitchen 1986 Table 4 counts to the Dynasty the rulers from Alara to Tanwetamani. -

Egypt and Nubia

9 Egypt and Nubia Robert Morkot THE, EGYPTIAN E,MPIRE,IN NUBIA IN THE LATE, BRONZE AGE (t.1550-l 070B CE) Introdu,ct'ion:sef-def,nit'ion an,d. the ,irnperi.ol con.cept in Egypt There can be litde doubt rhat the Egyptian pharaohs and the elite of the New I(ngdom viewed themselvesas rulers of an empire. This universal rule is clearly expressedin royal imagerv and terminology (Grimal f986). The pharaoh is styied asthe "Ruler of all that sun encircles" and from the mid-f 8th Dynasry the tides "I(ing of kings" and "Ruler of the rulers," with the variants "Lion" or "Sun of the Rulers," emphasizepharaoh's preeminence among other monarchs.The imagery of krngship is of the all-conquering heroic ruler subjecting a1lforeign lands.The lcingin human form smiteshis enemies.Or, asthe celestialconqueror in the form of the sphinx, he tramples them under foot. In the reigns of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten this imagery was exrended to the king's wife who became the conqueror of the female enemies of Egypt, appearing like her husbandin both human and sphinx forms (Morkot 1986). The appropriateter- minology also appeared; Queen Tiye became "Mistress of all women" and "Great of terror in the foreign lands." Empire, for the Egyptians,equals force - "all lands are under his feet." This metaphor is graphically expressedin the royal footstools and painted paths decorated \Mith images of bound foreign rulers, crushed by pharaoh as he walked or sar. This imagery and terminologv indicates that the Egyptian attirude to their empire was universally applied irrespective of the peoples or countries.