Chap 16 Newtopia for Guernica to Guggenheim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Human Rights Situation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex People in Europe and Central Asia

OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION OF LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, TRANS AND INTERSEX PEOPLE IN EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA FIND THIS REPORT ONLINE: WWW.ILGA-EUROPE.ORG THIS REVIEW COVERS THE PERIOD OF JANUARY TO DECEMBER 2019. Rue du Trône/Troonstraat 60 Brussels B-1050 Belgium Tel.: +32 2 609 54 10 Fax: + 32 2 609 54 19 [email protected] www.ilga-europe.org Design & layout: Maque Studio, www.maque.it ISBN 978-92-95066-11-3 FIND THIS REPORT ONLINE: WWW.ILGA-EUROPE.ORG Co-funded by the Rights Equality and Citizenship (REC) programme 2014-2020 of the European Union This publication has been produced with the financial support of the Rights Equality and Citizenship (REC) programme 2014-2020 of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of ILGA-Europe and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. ANNUAL REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION OF LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, TRANS, AND INTERSEX PEOPLE COVERING THE PERIOD OF JANUARY TO DECEMBER 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS KAZAKHSTAN INTRODUCTION KOSOVO* A NOTE ON DATA COLLECTION AND PRESENTATION KYRGYZSTAN HIGHLIGHTS, KEY DEVELOPMENTS AND TRENDS LATVIA INSTITUTIONAL REVIEWS LIECHTENSTEIN LITHUANIA EUROPEAN UNION LUXEMBOURG UNITED NATIONS MALTA COUNCIL OF EUROPE MOLDOVA ORGANISATION FOR SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE MONACO MONTENEGRO COUNTRY REVIEWS NETHERLANDS ALBANIA NORTH MACEDONIA ANDORRA NORWAY A ARMENIA POLAND AUSTRIA PORTUGAL AZERBAIJAN ROMANIA BELARUS RUSSIA BELGIUM SAN MARINO BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA SERBIA BULGARIA SLOVAKIA -

Panel Pool 2

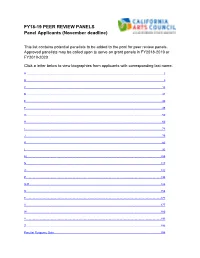

FY18-19 PEER REVIEW PANELS Panel Applicants (November deadline) This list contains potential panelists to be added to the pool for peer review panels. Approved panelists may be called upon to serve on grant panels in FY2018-2019 or FY2019-2020. Click a letter below to view biographies from applicants with corresponding last name. A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 B ............................................................................................................................................................................... 9 C ............................................................................................................................................................................. 18 D ............................................................................................................................................................................. 31 E ............................................................................................................................................................................. 40 F ............................................................................................................................................................................. 45 G ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

The Interface of Religious and Political Conflict in Egyptian Theatre

The Interface of Religious and Political Conflict in Egyptian Theatre Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amany Youssef Seleem, Stage Directing Diploma Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Lesley Ferris, Advisor Nena Couch Beth Kattelman Copyright by Amany Seleem 2013 Abstract Using religion to achieve political power is a thematic subject used by a number of Egyptian playwrights. This dissertation documents and analyzes eleven plays by five prominent Egyptian playwrights: Tawfiq Al-Hakim (1898- 1987), Ali Ahmed Bakathir (1910- 1969), Samir Sarhan (1938- 2006), Mohamed Abul Ela Al-Salamouni (1941- ), and Mohamed Salmawi (1945- ). Through their plays they call attention to the dangers of blind obedience. The primary methodological approach will be a close literary analysis grounded in historical considerations underscored by a chronology of Egyptian leadership. Thus the interface of religious conflict and politics is linked to the four heads of government under which the playwrights wrote their works: the eras of King Farouk I (1920-1965), President Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918-1970), President Anwar Sadat (1918-1981), and President Hosni Mubarak (1928- ). While this study ends with Mubarak’s regime, it briefly considers the way in which such conflict ended in the recent reunion between religion and politics with the election of Mohamed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, as president following the Egyptian Revolution of 2011. This research also investigates how these scripts were written— particularly in terms of their adaptation from existing canonical work or historical events and the use of metaphor—and how they were staged. -

Religion and Violence

Religion and Violence Edited by John L. Esposito Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions John L. Esposito (Ed.) Religion and Violence This book is a reprint of the special issue that appeared in the online open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) in 2015 (available at: http://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special_issues/ReligionViolence). Guest Editor John L. Esposito Georgetown University Washington Editorial Office MDPI AG Klybeckstrasse 64 Basel, Switzerland Publisher Shu-Kun Lin Assistant Editor Jie Gu 1. Edition 2016 MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan ISBN 978-3-03842-143-6 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03842-144-3 (PDF) © 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. All articles in this volume are Open Access distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC-BY), which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. However, the dissemination and distribution of physical copies of this book as a whole is restricted to MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. III Table of Contents List of Contributors ............................................................................................................... V Preface ............................................................................................................................... VII Jocelyne Cesari Religion and Politics: What Does God Have To Do with It? Reprinted from: Religions 2015, 6(4), 1330-1344 http://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/6/4/1330 ............................................................................ 1 Mark LeVine When Art Is the Weapon: Culture and Resistance Confronting Violence in the Post-Uprisings Arab World Reprinted from: Religions 2015, 6(4), 1277-1313 http://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/6/4/1277 ......................................................................... -

Nazis Decide to Defer Action More

r ?*■, M m a H n ititt Eafafno BmdA THUB8DAT, AOOUBT14, XtSi ATcroffa Daily Cirenlitien for tbe aMNth sf Joly, te n Dletaion No. «1 of the Oaaaral Dairy Company, BOO n a Waathar ~Walfara Canter, srlU hold Its raffuUr A bout Town School Board On the Watermelon Line Globe Carnival pepalektaa: Popular llarkat. hot *t O. 0. We maetlBff ITIday ersalng at algbt doga and watsnnaloas; Baysr Fruit 6 1 (1 1 o'clock In the EHst Side Raersatlaa HALE'S Member ef ths Audit aad Produce COmpaay, watermelons Shewers toolghtt BotoiWty g m - OalMBbo Soctotjr Center. Alfred Blatter, chairman of Proposal Filed Great Success and bananas; E t^body*s Market, Boraaa ef Clrcolstloas orally fair; aot much -*-ingii la lopt- k ■■>!«> plaw for Ita anauml baa- the advlaory committee, requaata all peanuts; Klttela Markst. water- SELF SERVE ! aad daaea and haa aet tha data members of hla committee to be at msloaa; Maaebtster Public Market, Manchester—-A City of Village Charm peratara, O ■nadajr, Oetobar IS. Tha affair tha Recreation Center by 7:i0 watsrmeloos; Flrat National Stores, sharp. 2:30 TO 5:30 FRIDAY will ba bald la tha Sub Alptna club A. R. Parish Nominated Attendance of 3,500 at watormslons; Hosser’s Market, can- VOL. LVIIL, NO. 278 (UaasUtod AdverttMag oe Page r MANCHESTER, CONN„ FRIDAY, AUGUST 25. 1939 aa B dildfa atxaat John Rota la As Primary Contestant; Pool Enjoyo INxigmin toloupes; Oewald’s Market, cookies; SPECIALS! (SIXTEEN PAGES) tba (taaral chalrmaa and Samuel office Associates Canals’* Market, cookies. PRICE THRBB CENTS S id a o la tha prealdent of the ao- Keating Makes Bid. -

2009 Annual Report MIGA’S Mission

2009 ANNUAL REPORT MIGA’s MISSION To promote foreign direct investment into developing countries to support economic growth, reduce poverty, and improve people’s lives. Guarantees Through its investment guarantees, MIGA offers protection for new cross-border investments, as well as expansions and privatizations of existing projects, against the following types of non-commercial risks:* r Currency inconvertibility and transfer restriction r Expropriation r War and civil disturbance r Breach of contract r Non-honoring of sovereign financial obligations As part of its guarantees program, MIGA provides dispute resolution services for guaranteed investments to prevent disruptions to developmentally beneficial projects. Technical Assistance MIGA helps countries define and implement strategies to promote investment through technical assistance services managed by the World Bank Group’s Foreign Investment Advisory Services (FIAS). Online Knowledge Services MIGA helps investors identify investment opportunities and manage risks through online investment information services—FDI.net and PRI-Center—offering infor- mation on investment opportunities, business operating conditions, and political risk insurance. * This report uses the terms “guarantees” and “insurance” interchangeably. The terms “non- commercial risk” and “political risk” are also used interchangeably throughout the report. CONTENTS MIGA’s Mission Summary of World Bank Group Activities ................................................... 2 Fiscal Year 2009 Highlights ............................................................................ -

Charity Art Auction in Favor of the CS Hospiz Rennweg in Cooperation with the Rotary Clubs Wien-West, Vienna-International, Köln-Ville and München-Hofgarten

Rotary Club Wien-West, Vienna-International, Our Auction Charity art Köln-Ville and München-Hofgarten in cooperation with That‘s how it‘s done: Due to auction 1. Register: the current, Corona- related situation, BenefizAuktion in favor of the CS Hospiz Rennweg restrictions and changes 22. February 2021 Go to www.cs.at/ charityauction and register there; may occur at any time. please register up to 24 hours before the start of the auction. Tell us the All new Information at numbers of the works for which you want to bid. www.cs.at/kunstauktion Alternatively, send us the buying order on page 128. 2. Bidding: Bidding live by phone: We will call you shortly before your lots are called up in the auction. You can bid live and directly as if you were there. Live via WhatsApp: When registering, mark with a cross that you want to use this option and enter your mobile number. You‘re in. We‘ll get in touch with you just before the auction. Written bid: Simply enter your maximum bid in the form for the works of art that you want to increase. This means that you can already bid up to this amount, but of course you can also get the bid for a lower value. Just fill out the form. L ive stream: at www.cs.at/kunstauktion you will find the link for the auction, which will broadcast it directly to your home. 3. Payment: You were able to purchase your work of art, we congratulate you very much and wish you a lot of pleasure with it. -

Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim

Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim Beyond Art and Politics from a Comparative Perspective a Comparative from Art and Politics Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim This book brings together experts from different fields of study, including sociology, anthropology, art history Art and Politics from a Comparative Perspective and art criticism to share their research and direct experience on the topic of art and politics. How art and politics relate with each other can be studied from numerous perspectives and standpoints. The book is structured according to three main themes: Part 1, on Valuing Art, broadly concerns the question of who, how and what value is given to art, and how this may change over time and circumstance, depending on the social and political situation and motivation of different interest groups. Part 2, on Artistic Political Engagement, reflects on another dimension of art and politics, that of how artists may be intentionally engaged with politics, either via their social and political status and/or through the kind of art they produce and how they frame it in terms of meaning. Part 3, on Exhibitions and Curating, focuses on yet another aspect of the relationship between art and politics: what gets exhibited, why, how, and with what political significance or consequence. A main focus is on the politics of art in the Basque Country, complemented by case studies and reflections from other parts of the world, both in the past and today. This book is unique by gathering a rich variety of different viewpoints and experiences, with artists, curators, art historians, sociologists and anthropologists talking to each other with sometimes quite different epistemological bases and methodological approaches. -

In Partnership With

In partnership with The United World College in Mostar 48 School year 2017/2018 News Contents 48 NEWS COLLEGE EVENTS A word from 3 International Day of Tolerance - a 13 UWC Mostar – the lighthouse of cooperation with OSCE Mission to education the editor... BiH 13 Promotion at the Education Fair 4 Šantić Residence and Diplomatic Winter Bazaar in am pleased to introduce the 4 €1 Alumni Giving Campaign Sarajevo first 2018 edition of the UWC 4 Cooperation with Booking.com - 14 Successful international Mostar Newsletter. This edition going on holiday and supporting cooperation continues the tradition of shar- UWC Mostar 14 History, Culture and Politics of ing UWC values and mission, INTERNATIONAL DAY OF TOLERANCE Switzerland at UWC Mostar Ipresenting articles on topics of inter- 5 Project weeks 2017 est related to the academic and ex- 6 Praise for organization of the 14 Workshops for Mostar Student - A COOPERATION WITH OSCE MISSION TO BIH tracurricular activities and projects at European Researchers’ Night in Council UWC Mostar. You can enjoy stories mostar 15 Supporting a good cause related to student organized events, SCE Mission to Bosnia and promotion of tolerance, multiculturalism of Mostar” said Valentina Mindoljević, success of our alumni as well as the 8 Helping people in need – UWCiM x Herzegovina in cooperation and respect. UWC Mostar Headmistress. Head Adviser great impact UWC Mostar brings to Refugees in Serbia ALUMNI STORIES with civil society coalitions and UWC Mostar students participated in of the City of Mostar Radmila Komadina the local community with organiza- 10 UWC X Campus Volunteers in 16 Interview: Learn, Earn and Return organizations marked the Inter- the event with traditional dances from stated that our city can be a great example tion of events intended for both Onational Day of Tolerance in Mostar. -

MAYBE SOMEONE WILL CARE Politics Between Art and Space

MAYBE SOMEONE WILL CARE Politics between art and space Picture 1. Borgerink Kris, ‘Whatever you will write on a wall, people won’t care’, 2008., Maybe someone will care Politics between art and space By Danijela Dugandžić, 2015 Originally published: in BHS language, publication “Šta da napišem na zidu”, Gradologija izdanje 03, 2015 Publisher: Association for Culture and Art CRVENA www.crvena.ba key words: #public space #art #politics #resistance #commons #politicalaction 2 A space open and available to all Public space is the space available to all. Local authorities rule the public space as a public good that includes: parks, streets, libraries, government institutions and the nature that surrounds us. It is the backbone of the identity of a city but, since ancient times, it represents the space for public discourse about everything that the citizens recognized as a political, economic or social problem. The ancient idea of public space as the arena for political liberation and participation as the foundation of democracy today is in conflict with the fact that public spaces are becoming places that are shaped by capital, which then creates means of perception and communication, thus creating more of a scenography, but also a place of potential resistance. Public space and public debate are using and forming signs, symbols and images to create what Lefevbre (1991) defines as representational space. Art, as a practice that, when presented in the public space, primarily deals with representation, can create a framework for political action. We have seen in many examples, such as the artworks of Banksy, Shepard Fairey, Alexandra Clotfelter and many others, how art uses the public space as the platform for a different politics, and how it turns out to be a sort of «public art». -

Citizenship Performance and Urban Social Space in Bogotá, 1985-2015

Confronting Violence: Citizenship Performance and Urban Social Space in Bogotá, 1985-2015 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Geoffrey Eugene Wilson B.A., M.F.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Ana Elena Puga, D.F.A., Advisor Jennifer Schlueter, Ph.D. Shilarna Stokes, Ph.D. Copyrighted by Geoffrey Eugene Wilson 2019 Abstract This dissertation combines performance analysis, cultural materialism, and theory on urban social space to develop a theory of citizenship performance. I analyze three performances that occurred in public spaces in Bogotá, Colombia each of which responds to violence resulting from Colombia’s long civil war and challenges dominant notions of who belongs to the cultural community, as well as how the community behaves collectively. I argue that citizenship performances respond to violence within Colombian culture in three ways: first, they remap community behavior by modelling alternative modes of public moral comportment; second, they destabilize and recode the symbolic languages of the cultural community; third, they assert the cultural citizenship of marginalized communities by presencing their lives, struggles, and histories in public social space. The first chapter analyzes a performance project by Bogotá’s alternative theatre company Mapa Teatro, that maps out the social histories of the former barrio Santa Inés, also known as El Cartucho. Beginning in 2001, Mapa Teatro began work on a series of performances and installations which documented the demolition of the barrio, culminating in a multimedia production called Witness to the Ruins, a citizenship performance that staged the lives of the former residents of Santa Inés on the rubble of the barrio itself, before it was transformed and gentrified into the Parque Tercer Milenio (Third Millennium Park). -

2010-2011 Financial Year Funding Recipients

2010-2011 Financial Year Funding Recipients NEGOTIATED Organisation Purpose/Program Name Funding $ Accessible Arts year 3 of triennial program funding A peak national body for NSW, providing a range of project and advocacy $240,875 (2009-2011) services within the arts and disability sectors. Arts Law Centre of Australia year 2 of triennial program funding Arts Law Centre of Australia is a specialist centre for artists and creators $123,000 (2010-2012) throughout Australia with arts-related queries including contracts, copyright, business structures, defamation etc. Where appropriate, provides free or low-cost telephone legal advice and referral services, professional development resources such as publications and presentations, and advocates for law reform. Arts Mid North Coast year 2 of triennial program funding Arts Mid North Coast is one of 14 Regional Arts Boards across NSW, $102,500 (2010-2012) each providing strategic direction for sustainable arts and cultural development in their region. The local councils in each area, together with the State Government, contribute financially to each Board to employ a Regional Arts Development Officer (RADO) and other support staff. This structure enables people who live in the regions to manage their own arts and cultural priorities for their own region. Mid North Coast services the people and communities of the Mid North Coast region, including the Coffs Harbour, Bellingen, Great Lakes, Kempsey, Nambucca, Greater Taree and Port Macquarie-Hastings local government areas. Arts North West Inc year 2 of triennial program funding Arts North West is one of 14 Regional Arts Boards across NSW, each $102,500 (2010-2012) providing strategic direction for sustainable arts and cultural development in their region.