Towards a Theory of Postmodern Humour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speaking of South Park

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 3 May 15th, 9:00 AM - May 17th, 5:00 PM Speaking of South Park Christina Slade University Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Slade, Christina, "Speaking of South Park" (1999). OSSA Conference Archive. 53. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA3/papersandcommentaries/53 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title: Speaking of South Park Author: Christina Slade Response to this paper by: Susan Drake (c)2000 Christina Slade South Park is, at first blush, an unlikely vehicle for the teaching of argumentation and of reasoning skills. Yet the cool of the program, and its ability to tap into the concerns of youth, make it an obvious site. This paper analyses the argumentation of one of the programs which deals with genetic engineering. Entitled 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig', the episode begins with the elephant being presented to the school bus driver as 'the new disabled kid'; and opens a debate on the virtues of genetic engineering with the teacher saying: 'We could have avoided terrible mistakes, like German people'. The show both offends and ridicules received moral values. However a fine grained analysis of the transcript of 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig' shows how superficially absurd situations conceal sophisticated argumentation strategies. -

View/Method……………………………………………………9

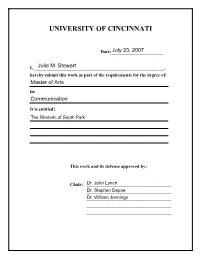

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________July 23, 2007 I, ________________________________________________Julie M. Stewart _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Communication It is entitled: The Rhetoric of South Park This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Dr. John Lynch _______________________________Dr. Stephen Depoe _______________________________Dr. William Jennings _______________________________ _______________________________ THE RHETORIC OF SOUTH PARK A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research Of the University of Cincinnati MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Communication, of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julie Stewart B.A. Xavier University, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. John Lynch Abstract This study examines the rhetoric of the cartoon South Park. South Park is a popular culture artifact that deals with numerous contemporary social and political issues. A narrative analysis of nine episodes of the show finds multiple themes. First, South Park is successful in creating a polysemous political message that allows audiences with varying political ideologies to relate to the program. Second, South Park ’s universal appeal is in recurring populist themes that are anti-hypocrisy, anti-elitism, and anti- authority. Third, the narrative functions to develop these themes and characters, setting, and other elements of the plot are representative of different ideologies. Finally, this study concludes -

South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review

south park the fractured but whole free download review South park the fractured but whole free download review. South Park The Fractured But Whole Crack Whole, players with Coon and Friends can dive into the painful, criminal belly of South Park. This dedicated group of criminal warriors was formed by Eric Cartman, whose superhero alter ego, The Coon, is half man, half raccoon. Like The New Kid, players will join Mysterion, Toolshed, Human Kite, Mosquito, Mint Berry Crunch, and a group of others to fight the forces of evil as Coon strives to make his team of the most beloved superheroes in history. Creators Matt South Park The Fractured But Whole IGG-Game Stone and Trey Parker were involved in every step of the game’s development. And also build his own unique superpowers to become the hero that South Park needs. South Park The Fractured But Whole Codex The player takes on the role of a new kid and joins South Park favorites in a new extremely shocking adventure. The game is the sequel to the award-winning South Park The Park of Truth. The game features new locations and new characters to discover. The player will investigate the crime under South Park. The other characters will also join the player to fight against the forces of evil as the crown strives to make his team the most beloved South Park The Fractured But Whole Plaza superheroes in history. Try Marvel vs Capcom Infinite for free now. The all-new dynamic control system offers new possibilities to manipulate time and space on the battlefield. -

Sacred Heart Parish St

WELCOME To The Regional Parishes of Tacoma March 24, 2019 Third Sunday of Lent Your Pastoral Team Fr. Tuan Nguyen, D. Min. Fr. Patrick McDermott Fr. James Harbaugh Regional Pastor Parochial Vicar Parochial Vicar 253-882-9943 360-556-4111 206-335-8385 [email protected] “I shall [email protected] [email protected] Emergency Contact Sr. Anna: (253) 592-2455 cultivate www.trparishes.org the ground Sacred Heart Parish St. Ann Parish St. John of the Woods 4520 McKinley Avenue 7025 South Park Avenue Parish Tacoma, WA 98404 Tacoma, WA 98408 9903 24th Avenue East around it (253) 472-7738 (253) 472-1360 Tacoma (Midland), WA 98445 Masses / Misas English Masses & (253) 537-8551 Reconciliation Sunday 10:00am English English Masses & Reconciliation: Sat.4:00pm and Mon & Fri 8:00am English Reconciliation Dominical Español Sábado Saturday Mass at 5:00pm Sunday Mass at 9:30am Reconciliation: 7:00pm fertilize it.” Domingo 8:00am y 12:00 Weekdays Mass: Sat. 4:30pm Medodía (Tue/Wed/Thu) 8:00am (E) Saturday Mass at 5:30pm Jueves 7:00pm Español Friday Mass at 7:00pm (V) Sunday Masses at 8:00am & Reconciliation / Con- Vietnamese Mass: 11:00am (Luke 13:9) fesiones Sunday Mass: 7:45 am Weekdays (Tue/Wed/Fri) Thursdays and Saturdays: Reconciliation: Sun. 3:00pm Mass at 9:30am from 6:00pm to 6:45pm Sunday Mass at 4:00pm Pastor’s Letter Dear Parishioners, We are in the Third Weekend of the Lenten journey with the Elects and Candidates. We thank you for continuing to support and pray for them during these Forty Days of their discernment towards the Baptismal Font and towards the Altar of the Eucha- ristic celebration! We thank their godparents and sponsors who are with them at each step of their journey. -

South Park - Winter 2019

Deerfield Park District After School Enrichments South Park - Winter 2019 Register online at register.deerfieldparks.org Registration opens Monday, November 26 at 9 am All Classes meet at South Park School. All students should meet in the multipurpose room for attendance. Please contact Mark Woolums at 847-572-2623 with any questions. WEEK AT A GLANCE Class Instructor Grade Art with Mari Mari Krasney K-5 Thunderbolts Flag Football Fit 4 Kids 1-4 Amazing Minds Amazing Minds K-2 Sticky Fingers Cooking Sticky Fingers Cooking K-5 Monday Class Instructor Grade Triple Play Hot Shot Sports K-3 Cartooning and More Susie Mason K-5 Cooking Taste Buds Kitchen 2-5 Little Footlighters Sarah Hall Theatre Company K-3 Yoga Movement Junkies K-5 Tuesday Class Instructor Grade Fit 4 Kids Fit 4 Kids K-3 Amazing Art Sunshine Crafts K-5 Guitar Sasha Brusin K-5 Spanish Fun Fluency 3-5 (Early) TechStars: Minecraft Mods & Sploder Computer Explorers 1-4 Wednesday Wednesday Cheerleading Soul 2 Soul Dance 3-5 Class Instructor Grade Lacrosse 5 Star Sports 1-4 TechStars: Game Design & Animation Computer Explorers 1-4 in 2D & 3D (Late) RubixFix Mr. Matthews 1-5 Wednesday Wednesday Spanish Fun Fluency 3-5 Class Instructor Grade Ceramics Richard Cohen K-5 Karate Focus Martial Arts K-5 Homework Club Mrs. Keidan 2-5 Sticky Fingers Cooking Sticky Fingers Cooking K-5 Pegasus FC Soccer Clinic Pegasus FC Soccer K-3 Thursday Class Instructor Grade Artopia Tiffany Shaf Plat K-5 Chess Chess Scholars K-5 Lil Dribblers Basketball Hot Shot Sports K-3 Friday Monday 1/14 - 3/18 | Time: 3:35 - 4:35 pm 7 Classes | No class 1/21, 2/18, 3/4 Art with Mari thunderbolts Amazing Activity # 251610-01 Flag Football Minds K-5 Grade | Fee: $120 Students will create multi-media Activity # 251610-02 Activity # 251610-03 projects, introducing them to a 1-4 Grade | Fee: $188 K-2 Grade | Fee: $157 variety of media including pencil, Thunderbolts: Join us this fall for Explore interesting topics and learn to watercolor, and acrylic. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, the Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2009-01-01 South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Dungan, Drew W., "South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism" (2009). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 245. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/245 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan Department of Communication APPROVED: Richard D. Pineda, Ph.D., Chair Stacey Sowards, Ph.D. Robert L. Gunn, Ph.D. Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Drew W. Dungan 2009 Dedication To all who have been patient and kind, most of all Robert, Thalia, and Jesus, thank you for everything... South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies. The Art of Stealthy Conservatism by DREW W. DUNGAN, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2009 Abstract South Park serves as an example of satire and parody lampooning culture war issues in the popular media. -

De Representatie Van Leraren En Onderwijs in Populaire Cultuur. Een Retorische Analyse Van South Park

Universiteit Gent, Faculteit Psychologie en Pedagogische Wetenschappen Academiejaar 2014-2015 De representatie van leraren en onderwijs in populaire cultuur. Een retorische analyse van South Park Jasper Leysen 01003196 Promotor: Dr. Kris Rutten Masterproef neergelegd tot het behalen van de graad van master in de Pedagogische Wetenschappen, afstudeerrichting Pedagogiek & Onderwijskunde Voorwoord Het voorwoord schrijven voelt als een echte verlossing aan, want dit is het teken dat mijn masterproef is afgewerkt. Anderhalf jaar heb ik op geregelde basis gezwoegd, gevloekt en getwijfeld, maar het overheersende gevoel is toch voldoening. Voldoening om een werk af te hebben waar veel tijd en moeite is ingekropen. Voldoening om een werk af te hebben waar ik toch wel fier op ben. Voldoening om een werk af te hebben dat ik zelfstandig op poten heb gezet en heb afgewerkt. Althans hoofdzakelijk zelfstandig, want ik kan er niet omheen dat ik regelmatig hulp heb gekregen van mensen uit mijn omgeving. Het is dan ook niet meer dan normaal dat ik ze hier even bedank. In de eerste plaats wil ik mijn promotor, dr. Kris Rutten, bedanken. Ik kon steeds bij hem terecht met vragen en opmerkingen en zijn feedback gaf me altijd nieuwe moed en inspiratie om aan mijn thesis verder te werken. Ik apprecieer vooral zijn snelle en efficiënte manier van handelen. Nooit heb ik lang moeten wachten op een antwoord, nooit heb ik vele uren zitten verdoen op zijn bureau. Bedankt! Ten tweede wil ik ook graag Ayna, Detlef, Diane, Katoo, Laure en Marijn bedanken voor deelname aan mijn focusgroep. Hun inzichten hebben ervoor gezorgd dat mijn analyses meer gefundeerd werden, hun enthousiasme heeft ertoe bijgedragen dat ik besefte dat mijn thesis zeker een bijdrage is voor het onderzoeksveld. -

Symbolism and the Thirteenth Amendment: the Injury of Exposure to Governmentally Endorsed Symbols of Racial Superiority

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 25 2020 Symbolism and the Thirteenth Amendment: The Injury of Exposure to Governmentally Endorsed Symbols of Racial Superiority Edward H. Kyle St. John’s University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Edward H. Kyle, Symbolism and the Thirteenth Amendment: The Injury of Exposure to Governmentally Endorsed Symbols of Racial Superiority, 25 MICH. J. RACE & L. 77 (2019). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol25/iss1/5 https://doi.org/10.36643/mjrl.25.1.thirteenth This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYMBOLISM AND THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT: THE INJURY OF EXPOSURE TO GOVERNMENTALLY ENDORSED SYMBOLS OF RACIAL SUPERIORITY By Edward H. Kyle III J.D., St. John’s University School of Law 2019 Acknowledgment: I would like to acknowledge the guidance of Prof. John Q. Barrett in the drafting of this Article and my wife, Christine, and daughter, Gracie Lou, for their love and support during its creation. Table of Contents Table of Authorities..............................................................................78 I. Introduction: The Case of Moore v. Bryant................................81 II. Article III Standing and the Badges of Slavery...........................85 A. -

Listado Obras Reparto Extraordinario SOGECABLE Emisión Analógica.Xlsx

Listado de obras audiovisuales Reparto Extraordinario SOGECABLE (Emisión Analógica) Canal Plus 1995 - 2005 Cuatro 2005 - 2009 Dossier informativo Departamento de Reparto Página 1 de 818 Tipo Código Titulo Tipo Año Protegida Obra Obra Obra Producción Producción Globalmente Actoral 20021 ¡DISPARA! Cine 1993 Actoral 17837 ¡QUE RUINA DE FUNCION! Cine 1992 Actoral 201670 ¡VAYA PARTIDO!- Cine 2001 Actoral 17770 ¡VIVEN!- Cine 1993 Actoral 136956 ¿DE QUE PLANETA VIENES?- Cine 2000 Actoral 74710 ¿EN VIVO O EN VITRO? Cine 1996 Actoral 53383 ¿QUE HAGO YO AQUI, SI MAÑANA ME CASO? Cine 1994 Actoral 175 ¿QUE HE HECHO YO PARA MERECER ESTO? Cine 1984 Actoral 20505 ¿QUIEN PUEDE MATAR A UN NIÑO? Cine 1976 Actoral 12776 ¿QUIEN TE QUIERE BABEL? Cine 1987 Actoral 102285 101 DALMATAS (MAS VIVOS QUE NUNCA)- Cine 1996 Actoral 134892 102 DALMATAS- Cine 2000 Actoral 99318 12:01 TESTIGO DEL TIEMPO- Cine 1994 Actoral 157523 13 CAMPANADAS Cine 2001 Actoral 135239 15 MINUTOS- Cine 2000 Actoral 256494 20.000 LEGUAS DE VIAJE SUBMARINO I- Cine 1996 Actoral 256495 20.000 LEGUAS DE VIAJE SUBMARINO II- Cine 1996 Actoral 102162 2013 RESCATE EN L.A.- Cine 1995 Actoral 210841 21 GRAMOS- Cine 2003 Actoral 105547 28 DIAS Cine 2000 Actoral 165951 28 DIAS DESPUES Cine 2002 Actoral 177692 3 NINJAS EN EL PARQUE DE ATRACCIONES- Cine 1998 Actoral 147123 40 DIAS Y 40 NOCHES- Cine 2002 Actoral 126095 60 SEGUNDOS- Cine 2000 Actoral 247446 69 SEGUNDOS (X) Cine 2004 Actoral 147857 8 MILLAS- Cine 2002 Actoral 157897 8 MUJERES Cine 2002 Actoral 100249 8 SEGUNDOS- Cine 1994 Página 2 de 818 -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised. -

Full Brief (.Pdf)

No. 15-1293 In the Supreme Court of the United States __________ Michelle K. Lee, Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director, United States Patent and Trademark Office, Petitioner, v. Simon Shiao Tam, Respondent. __________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit __________ BRIEF OF THE CATO INSTITUTE AND A BASKET OF DEPLORABLE PEOPLE AND ORGANIZATIONS AS AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING RESPONDENT __________ Ilya Shapiro Counsel of Record Thomas A. Berry CATO INSTITUTE 1000 Mass. Ave., N.W. Washington, DC 20001 (202) 842-0200 [email protected] [email protected] December 16, 2016 i QUESTION PRESENTED Does the government get to decide what’s a slur? ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTION PRESENTED .......................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... iv INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................... 1 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 7 I. “DISPARAGING” LANGUAGE SERVES AN IMPORTANT ROLE IN OUR SOCIETY ........... 7 A. Reclaiming Slurs Has Played a Big Part in Personal Expression and Cultural Debate ... 7 B. Rock Music Has a Proud Tradition of Pushing the Boundaries of Expression ...... 10 II. THE GOVERNMENT SHOULD NOT BE DECIDING WHAT’S A SLUR .......................... 12 A. It Is Impossible to Draw an Objective Line as to What Is Disparaging .......................... 12 B. Brands That Do Not Wish to Offend Can Change Their Names Voluntarily .............. 19 III. THE DISPARAGEMENT CLAUSE VIOLATES THE FIRST AMENDMENT ......... 22 A. The Disparagement Clause Is a Viewpoint-Based Unconstitutional Condition ..................................................... 22 B. A Trademark Is Neither a Subsidy Nor an Endorsement .......................................... 23 1. Choosing which artists and speakers to fund with limited resources is different than trademark registration.