Boondocks Vs. South Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speaking of South Park

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 3 May 15th, 9:00 AM - May 17th, 5:00 PM Speaking of South Park Christina Slade University Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Slade, Christina, "Speaking of South Park" (1999). OSSA Conference Archive. 53. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA3/papersandcommentaries/53 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title: Speaking of South Park Author: Christina Slade Response to this paper by: Susan Drake (c)2000 Christina Slade South Park is, at first blush, an unlikely vehicle for the teaching of argumentation and of reasoning skills. Yet the cool of the program, and its ability to tap into the concerns of youth, make it an obvious site. This paper analyses the argumentation of one of the programs which deals with genetic engineering. Entitled 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig', the episode begins with the elephant being presented to the school bus driver as 'the new disabled kid'; and opens a debate on the virtues of genetic engineering with the teacher saying: 'We could have avoided terrible mistakes, like German people'. The show both offends and ridicules received moral values. However a fine grained analysis of the transcript of 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig' shows how superficially absurd situations conceal sophisticated argumentation strategies. -

View/Method……………………………………………………9

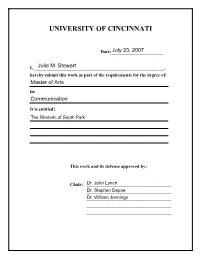

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________July 23, 2007 I, ________________________________________________Julie M. Stewart _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Communication It is entitled: The Rhetoric of South Park This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Dr. John Lynch _______________________________Dr. Stephen Depoe _______________________________Dr. William Jennings _______________________________ _______________________________ THE RHETORIC OF SOUTH PARK A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research Of the University of Cincinnati MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Communication, of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julie Stewart B.A. Xavier University, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. John Lynch Abstract This study examines the rhetoric of the cartoon South Park. South Park is a popular culture artifact that deals with numerous contemporary social and political issues. A narrative analysis of nine episodes of the show finds multiple themes. First, South Park is successful in creating a polysemous political message that allows audiences with varying political ideologies to relate to the program. Second, South Park ’s universal appeal is in recurring populist themes that are anti-hypocrisy, anti-elitism, and anti- authority. Third, the narrative functions to develop these themes and characters, setting, and other elements of the plot are representative of different ideologies. Finally, this study concludes -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review

south park the fractured but whole free download review South park the fractured but whole free download review. South Park The Fractured But Whole Crack Whole, players with Coon and Friends can dive into the painful, criminal belly of South Park. This dedicated group of criminal warriors was formed by Eric Cartman, whose superhero alter ego, The Coon, is half man, half raccoon. Like The New Kid, players will join Mysterion, Toolshed, Human Kite, Mosquito, Mint Berry Crunch, and a group of others to fight the forces of evil as Coon strives to make his team of the most beloved superheroes in history. Creators Matt South Park The Fractured But Whole IGG-Game Stone and Trey Parker were involved in every step of the game’s development. And also build his own unique superpowers to become the hero that South Park needs. South Park The Fractured But Whole Codex The player takes on the role of a new kid and joins South Park favorites in a new extremely shocking adventure. The game is the sequel to the award-winning South Park The Park of Truth. The game features new locations and new characters to discover. The player will investigate the crime under South Park. The other characters will also join the player to fight against the forces of evil as the crown strives to make his team the most beloved South Park The Fractured But Whole Plaza superheroes in history. Try Marvel vs Capcom Infinite for free now. The all-new dynamic control system offers new possibilities to manipulate time and space on the battlefield. -

Stream South Park Online Free No Download Stream South Park Online Free No Download

stream south park online free no download Stream south park online free no download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67dbdf08ddb7c40b • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Stream south park online free no download. Watch full episodes of your favorite shows with the Comedy Central app.. Enjoy South Park, The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, Broad City and many more, . New episodes of “South Park” will now go through many windows — on television on Comedy Central, on the web at SouthParkStudios for . How to watch South Park on South Park Studios: · Go to: http://southpark.cc.com/.. · Select “Full episodes” from the top menu.. south park episodes. South Park Zone South Park Season 23.. Watch all South Park episodes from Season 23 online . "Mexican Joker" is the first episode of the twenty-third season of . seasons from many popular shows exclusively streaming on Hulu including Seinfeld, Fargo, South Park and Fear the Walking Dead. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, the Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2009-01-01 South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Dungan, Drew W., "South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism" (2009). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 245. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/245 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan Department of Communication APPROVED: Richard D. Pineda, Ph.D., Chair Stacey Sowards, Ph.D. Robert L. Gunn, Ph.D. Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Drew W. Dungan 2009 Dedication To all who have been patient and kind, most of all Robert, Thalia, and Jesus, thank you for everything... South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies. The Art of Stealthy Conservatism by DREW W. DUNGAN, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2009 Abstract South Park serves as an example of satire and parody lampooning culture war issues in the popular media. -

PDF Download South Park Drawing Guide : Learn To

SOUTH PARK DRAWING GUIDE : LEARN TO DRAW KENNY, CARTMAN, KYLE, STAN, BUTTERS AND FRIENDS! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Go with the Flo Books | 100 pages | 04 Dec 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781519695369 | English | none South Park Drawing Guide : Learn to Draw Kenny, Cartman, Kyle, Stan, Butters and Friends! PDF Book Meanwhile, Butters is sent to a special camp where they "Pray the Gay Away. See more ideas about south park, south park anime, south park fanart. After a conversation with God, Kenny gets brought back to life and put on life support. This might be why there seems to be an air of detachment from Stan sometimes, either as a way to shake off hurt feelings or anger and frustration boiling from below the surface. I was asked if I could make Cartoon Animals. Whittle his Armor down and block his high-powered attacks and you'll bring him down, faster if you defeat Sparky, which lowers his defense more, which is recommended. Butters ends up Even Butters joins in when his T. Both will use their boss-specific skill on their first turn. Garrison wielding an ever-lively Mr. Collection: Merry Christmas. It is the main protagonists in South Park cartoon movie. Climb up the ladder and shoot the valve. Donovan tells them that he's in the backyard. He can later be found on the top ramp and still be aggressive, but cannot be battled. His best friend is Kyle Brovlovski. Privacy Policy.. To most people, South Park will forever remain one of the quirkiest and wittiest animated sitcoms created by two guys who can't draw well if their lives depended on it. -

PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues Through Satire

Colloquy Vol. 12, Fall 2016, pp. 101-114 PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues through Satire Alex Dejean Abstract This study takes an extensive look at the television program South Park episode “Stunning and Brave.” There is limited research that explores the use of satire to create social discourse on concepts related to political correctness. I use framing theory as a primary variable to understand the messages “Stunning and Brave” attempts to convey. Framing theory originated from the theory of agenda setting. Agenda setting explains how media depictions affect how people think about the world. Framing is an aspect of agenda setting that details the organization and structure of a narrative or story. Framing is such an important variable to agenda setting that research on framing has become its own field of study. Existing literature of framing theory, comedy, and television has shown how audiences perceive issues once they have been exposed to media messages. The purpose of this research will review relevant literature explored in this area to examine satirical criticism on the social issue of political correctness. It seems almost unnecessary to point out the effect media has on us every day. Media is a broad term for the collective entities and structures through which messages are created and transmitted to an audience. As noted by Semmel (1983), “Almost everyone agrees that the mass media shape the world around us” (p. 718). The media tells us what life is or what we need for a better life. We have been bombarded with messages about what is better. -

Listado Obras Reparto Extraordinario SOGECABLE Emisión Analógica.Xlsx

Listado de obras audiovisuales Reparto Extraordinario SOGECABLE (Emisión Analógica) Canal Plus 1995 - 2005 Cuatro 2005 - 2009 Dossier informativo Departamento de Reparto Página 1 de 818 Tipo Código Titulo Tipo Año Protegida Obra Obra Obra Producción Producción Globalmente Actoral 20021 ¡DISPARA! Cine 1993 Actoral 17837 ¡QUE RUINA DE FUNCION! Cine 1992 Actoral 201670 ¡VAYA PARTIDO!- Cine 2001 Actoral 17770 ¡VIVEN!- Cine 1993 Actoral 136956 ¿DE QUE PLANETA VIENES?- Cine 2000 Actoral 74710 ¿EN VIVO O EN VITRO? Cine 1996 Actoral 53383 ¿QUE HAGO YO AQUI, SI MAÑANA ME CASO? Cine 1994 Actoral 175 ¿QUE HE HECHO YO PARA MERECER ESTO? Cine 1984 Actoral 20505 ¿QUIEN PUEDE MATAR A UN NIÑO? Cine 1976 Actoral 12776 ¿QUIEN TE QUIERE BABEL? Cine 1987 Actoral 102285 101 DALMATAS (MAS VIVOS QUE NUNCA)- Cine 1996 Actoral 134892 102 DALMATAS- Cine 2000 Actoral 99318 12:01 TESTIGO DEL TIEMPO- Cine 1994 Actoral 157523 13 CAMPANADAS Cine 2001 Actoral 135239 15 MINUTOS- Cine 2000 Actoral 256494 20.000 LEGUAS DE VIAJE SUBMARINO I- Cine 1996 Actoral 256495 20.000 LEGUAS DE VIAJE SUBMARINO II- Cine 1996 Actoral 102162 2013 RESCATE EN L.A.- Cine 1995 Actoral 210841 21 GRAMOS- Cine 2003 Actoral 105547 28 DIAS Cine 2000 Actoral 165951 28 DIAS DESPUES Cine 2002 Actoral 177692 3 NINJAS EN EL PARQUE DE ATRACCIONES- Cine 1998 Actoral 147123 40 DIAS Y 40 NOCHES- Cine 2002 Actoral 126095 60 SEGUNDOS- Cine 2000 Actoral 247446 69 SEGUNDOS (X) Cine 2004 Actoral 147857 8 MILLAS- Cine 2002 Actoral 157897 8 MUJERES Cine 2002 Actoral 100249 8 SEGUNDOS- Cine 1994 Página 2 de 818 -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised. -

The Governor – Issue 16

ESTABLISHED 1959 May 6, 2016 WWW.THEGOVERNORNEWSPAPER.COM WorldNews NO CHANGE IS GOOD CHANGE? HeatherSkinner ‘17 Andrew Jackson’s When the Red Stick Indians point out that not every Indian transfer federal funds to state economic disaster. Her accom- being replaced on the twen- returned home they found that cried. The 4,000 Indians who banks. Two Secretaries of the plishments can be summed up ty-dollar bill is an outrage. Jackson had created a fort on did die were the weak, who Treasury opposed this idea, but by her looks, and they are cer- Jackson was a war hero and a their holy ground. He then couldn’t handle a little bit of they weren’t as fiscally edu- tainly lacking. Jackson helped president, an essential part of seized 22 million acres of their walking and hunger. Jackson’s cated as Jackson. He trans- to expand our land; all Harriet our nation’s glorious history. land. Jackson’s war tactics Indian removal plans were a ferred $10 million (that’s a Tubman ever did was to fuel In 1828 Jackson was elected earned him the title as a hero, “gentle” push to expand our lot of twenties) to state funds, the abolitionist movement and President of this great nation and rightfully so. During his nation. which precipitated an inflation singlehandedly bring 70 slaves and in 1928, a 100 years later, presidency Jackson worked to The idea that Jackson of land prices and a flood of to freedom. Tubman wasn’t we commemorated his presi- expand our great nation with a almost single handedly de- paper money, which even the even a President; we haven’t dency by slapping his face on plan of “forcible relocation” of stroyed the US banking system smartest economist couldn’t had a woman President (ob- the twenty-dollar bill.