Survey of Economic and Social Developments in the ESCWA Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fossil Fuels………………………………………………

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Relazioni Internazionali Comparate Tesi di Laurea Energy and Environment Between development and sustainability Relatore Ch. Prof. Matteo Legrenzi Correlatore Ch. Prof. Duccio Basosi Laureando Alberto Lora Matricola 987611 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………i Introduction...………………………………………………………….........................................1 PART 1 - ENERGY SECURITY Chapter 1. Energy Security……………………………………………………………………...7 1.1 What is energy security?.......................................................................................................7 1.1.1 Definition of energy security…………………………………………………………………………..7 1.1.2 Elements of energy security………………………………………………………………………….8 1.1.3 Different interpretations of energy security………………………………………………………….9 1.1.4 Theories about energy security……………………………………………………………………..11 1.2 Diversification of the energy mix…………………………………………………………………12 1.2.1 Types of energy sources………………………………..............................................................12 1.2.2 Definition of energy mix……………………………………………………………………………..13 1.3 Growing risks………………………………………………………………………………………16 1.3.1 Energy insecurity……………………………………………………………………………………..16 1.3.2 Geological risk………………………………………………………………………………………..17 1.3.3 Geopolitical risk…………………………………………………………………….........................18 1.3.4 Economic risk…………………………………………………………………………………………22 1.3.5 Environmental risk……………………………………………………………………………………22 1.3.6 Solutions………………………………………………………………………………………………23 -

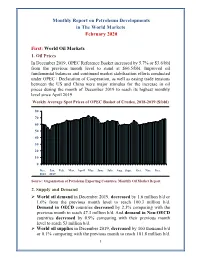

Monthly Report on Petroleum Developments in the World Markets February 2020

Monthly Report on Petroleum Developments in The World Markets February 2020 First: World Oil Markets 1. Oil Prices In December 2019, OPEC Reference Basket increased by 5.7% or $3.6/bbl from the previous month level to stand at $66.5/bbl. Improved oil fundamental balances and continued market stabilization efforts conducted under OPEC+ Declaration of Cooperation, as well as easing trade tensions between the US and China were major stimulus for the increase in oil prices during the month of December 2019 to reach its highest monthly level since April 2019. Weekly Average Spot Prices of OPEC Basket of Crudes, 2018-2019 ($/bbl) 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Dec. Jan. Feb. Mar. April May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec. 2018 2019 Source: Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, Monthly Oil Market Report. 2. Supply and Demand World oil demand in December 2019, decreased by 1.6 million b/d or 1.6% from the previous month level to reach 100.3 million b/d. Demand in OECD countries decreased by 2.3% comparing with the previous month to reach 47.3 million b/d. And demand in Non-OECD countries decreased by 0.9% comparing with their previous month level to reach 53 million b/d. World oil supplies in December 2019, decreased by 100 thousand b/d or 0.1% comparing with the previous month to reach 101.8 million b/d. 1 Non-OPEC supplies remained stable at the same previous month level of 67.2 million b/d. Whereas preliminary estimates show that OPEC crude oil and NGLs/condensates total supplies decreased by 0.6% comparing with the previous month to reach 34.5 million b/d. -

Crude Oil Price Movements

OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report 11 July 2018 Feature article: Oil Market Outlook for 2019 Oil market highlights iii Feature article v Crude oil price movements 1 Commodity markets 8 World economy 11 World oil demand 31 World oil supply 44 Product markets and refinery operations 63 Tanker market 71 Oil trade 76 Stock movements 81 Balance of supply and demand 87 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Helferstorferstrasse 17, A-1010 Vienna, Austria E-mail: prid(at)opec.org Website: www.opec.org Welcome to the Republic of the Congo Welcome to the Republic of the Congo as the 15th OPEC Member The 174th Meeting of the Conference approved the request from the Republic of the Congo to join the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), with immediate effect from 22nd June 2018. In line with this development, data for the Republic of the Congo is now included within the OPEC grouping. As a result, the figures for OPEC crude production, demand for OPEC crude and non-OPEC supply as well as the OPEC Reference Basket have been adjusted to reflect this change. For comparative purposes, related historical data has also been revised. OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report – July 2018 i Welcome the Republic of Congo ii OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report – July 2018 Oil Market Highlights Oil Market Highlights Crude Oil Price Movements The OPEC Reference Basket (ORB) eased by 1.2% month-on-month (m-o-m) in June to average $73.22/b. The ORB ended 1H18 higher at $68.43/b, up more than 36% since the start of the year. -

In Yemen, 2012

Updated Food Security Monitoring Survey Yemen Final Report September 2013 Updated Food Security Monitoring Survey (UFSMS), Yemen, Sept. 2013 Foreword Food insecurity and malnutrition are currently among the biggest challenges facing Yemen. Chronic malnutrition in the country is unacceptably high – the second highest rate in the world. Most of Yemen’s governorates are at critical level according to classifications by the World Health Organization. While the ongoing social safety net support provided by the government’s Social Welfare Fund has prevented many poor households from sliding into total destitution, WFP’s continued humanitarian aid operations in collaboration with government and partners have helped more than 5 million severely food insecure people to manage through difficult times in 2012 and 2013. However, their level of vulnerability has remained high, as most of those food insecure people have been forced to purchase food on credit, become more indebted and to use other negative coping strategies - and their economic condition has worsened during the past two years. Currently, about 10.5 million people in Yemen are food insecure, of whom 4.5 million are severely food insecure and over 6 million moderately food insecure. The major causes of the high levels of food insecurity and malnutrition include unemployment, a reduction in remittances, deterioration in economic growth, extreme poverty, high population growth, volatility of prices of food and other essential commodities, increasing cost of living including unaffordable health expenses, and insecurity. While the high level of negative coping strategies being used by food-insecure households continues, the food security outlook does not look better in 2014, as the major causes of current food insecurity are likely to persist in the coming months, and may also be aggravated by various factors such as uncertainties in the political process, declining purchasing power, and continued conflicts and the destruction of vital infrastructure including oil pipelines and electricity power lines. -

Asymmetric Impacts of Oil Price on Inflation: an Empirical Study

energies Article Asymmetric Impacts of Oil Price on Inflation: An Empirical Study of African OPEC Member Countries Umar Bala 1,2 and Lee Chin 2,* 1 Department of Economics, Faculty of Management and Social Sciences, Bauchi State University, P.M.B. 65 Gadau, Nigeria; [email protected] 2 Department of Economics, Faculty of Economics and Management, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +60-603-8946-7769 Received: 14 August 2018; Accepted: 26 October 2018; Published: 2 November 2018 Abstract: This study investigates the asymmetric impacts of oil price changes on inflation in Algeria, Angola, Libya, and Nigeria. Three different kinds of oil price data were applied in this study: the actual spot oil price of individual countries, the OPEC reference basket oil price, and an average of the Brent, WTI, and Dubai oil price. Autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) dynamic panels were used to estimate the short- and long-term impacts. Also, we partitioned the oil price into positive and negative changes to capture asymmetric impacts and found that both the positive and negative oil price changes positively influenced inflation. However, the impact was found to be more significant when the oil prices dropped. We also found that the money supply, the exchange rate, and the gross domestic product (GDP) are positively related to inflation, while food production is negatively related to inflation. Accordingly, policy-makers should be cautious when formulating policies between the positive and negative changes in oil prices, as it was shown that inflation increased when the oil price dropped. -

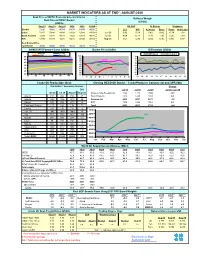

Market Indicators As at End*: August-2020

MARKET INDICATORS AS AT END*: AUGUST-2020 Spot Price of OPEC Basket & Selected Crudes Refiners' Margin Real Price of OPEC Basket (US$/b) (US$/b) Aug-18 Aug-19 Aug-20 2018 2019 2020# US Gulf N. Europe Singapore Basket 72.26 59.62 45.19 69.78 64.04 40.50 LLS WTI A. Heavy Brent Oman Arab Light Dubai 72.47 58.88 43.89 69.68 63.48 41.54 Jun-20 3.92 5.19 0.42 0.42 -0.74 1.02 North Sea Dtd 72.64 58.83 44.79 71.22 64.19 40.88 Jul-20 4.64 6.13 -1.86 1.30 1.26 1.99 WTI 67.99 54.84 42.36 65.16 57.02 38.15 Aug-20 3.67 5.30 -2.05 0.16 0.86 0.87 Real Basket Price Jun01=100 46.86 39.02 28.30 35.22 44.73 26.19 NYMEX WTI Forward Curve (US$/b) Basket Price (US$/b) Differentials (US$/b) May-20 Jun-20 WTI-Brent Brent-Dubai Jul-20 Aug-20 50 100 3 90 2 45 2018 80 1 70 40 0 60 35 2019 -1 50 30 40 -2 2020 -3 25 30 20 -4 20 10 -5 1M 3M 5M 7M 9M 11M J F M A M J J A S O N D 03 05 07 11 13 17 19 21 25 27 31 Crude Oil Production (tb/d) Closing OECD Oil Stocks - Crude/Products Commercial and SPR (Mb) Crude Oil Production (Tb/d) Production: Secondary Sources Change Diff. -

Oil and Security Policies

Oil and Security Policies <UN> International Comparative Social Studies Editor-in-Chief Mehdi P. Amineh (Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research, University of Amsterdam, International Institute for Asian Studies, University of Leiden) Editorial Board Sjoerd Beugelsdijk (Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) Simon Bromley (Open University, uk) Harald Fuhr (University of Potsdam, Germany) Gerd Junne (University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Kurt W. Radtke (International Institute for Asian Studies, The Netherlands) Ngo Tak-Wing (University of Leiden, The Netherlands) Mario Rutten (University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Advisory Board W.A. Arts (University College Utrecht, The Netherlands) G.C.M. Lieten (University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands) H.W. van Schendel (University of Amsterdam/International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam) L.A. Visano (York University, Canada) VOLUME 32 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/icss <UN> Oil and Security Policies Saudi Arabia, 1950–2012 By Islam Y. Qasem LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> Cover illustration: © Ruletkka|Dreamstime.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Qasem, Islam Y., author. Oil and security policies : Saudi Arabia, 1950-2012 / by Islam Y. Qasem. pages cm. -- (International comparative social studies, ISSN 1568-4474 ; volume 32) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-27774-8 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Petroleum industry and trade--Political aspects--Saudi Arabia. 2. Energy consumption--Political aspects--Saudi Arabia. 3. Internal security--Saudi Arabia. 4. National security--Saudi Arabia. 5. Security, International--Saudi Arabia. 6. Saudi Arabia--Foreign relations. I. Title. HD9576.S32Q26 2015 338.2’72820953809045--dc23 2015028649 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. -

Entre La Inestabilidad Y El Colapso, Yemen, El Fracaso Del Proyecto Republicano

MASTER EN RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES Departamento de Derecho Internacional Público y Relaciones Internacionales Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociología UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Entre la inestabilidad y el colapso, Yemen, el fracaso del proyecto republicano Moisés García Corrales Trabajo de investigación de final de Máster dirigido por la profesora Paloma González del Miño Yemen, el fracaso del proyecto republicano__________________________________________________ ENTRE LA INESTABILIDAD Y EL COLAPSO: YEMEN, EL FRACASO DEL PROYECTO REPUBLICANO Introducción metodológica Identificación del objeto de investigación Motivación del tema de estudio Delimitación temporal Formulación del tema de estudio Formulación de la hipótesis de partida I. El sistema político y la gobernanza en la República de Yemen 1. INTRODUCCIÓN HISTÓRICA 1.1. La división de Yemen: un país, dos naciones 1.2. La unificación de Yemen: el proyecto republicano 2. LA REALIDAD TRIBAL FRENTE A LA REALIDAD ESTATAL 3. EL PROYECTO REPUBLICANO Y SU DERIVA POLÍTICA 3.1. El constitucionalismo en la República de Yemen 3.1.1. El sistema constitucional y sus reformas 3.1.2. Los derechos y deberes ciudadanos 3.2. El Gobierno y la gobernanza en la República de Yemen 3.2.1. El sistema de partidos 3.2.2. La sucesión presidencial Yemen, el fracaso del proyecto republicano__________________________________________________ 3.2.3. El papel de las Fuerzas Armadas 3.2.4. La descentralización 3.2.5. La lucha contra la corrupción II. El fracaso del proyecto republicano de unificación 4. LOS CONFLICTOS DESEQUILIBRANTES DE LA REPÚBLICA DE YEMEN 4.1. El borde del colapso 4.2. Disidencias y rebeliones internas 4.2.1. Insurgencia huthi en la gobernación de Saada (a) Las causas pendientes del zaydismo (b) Al Qaeda e Irán: la sombra de la duda (c) Desarrollo del conflicto 4.2.2. -

Monthly Oil Market Report

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries OMonthlyP Oil MEarket CReport March 2005 Feature Article: Relationship between commercial crude inventories and oil prices Oil Market Highlights 1 Feature Article 3 Outcome of the 135th Meeting of the Conference 5 Highlights of the world economy 7 Crude oil price movements 11 Product markets and refinery operations 15 The oil futures market 19 The tanker market 21 World oil demand 23 World oil supply 28 Rig count 31 Stock movements 32 Balance of supply and demand 34 Obere Donaustrasse 93, A-1020 Vienna, Austria Tel: +43 1 21112 Fax: +43 1 2164320 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.opec.org ____________________________________________________________________Monthly Oil Market Report Oil Market Highlights For the first time since the summer of 2004, Japan and Europe appear to have begun to share in the growth of the world economy. The outlook for Japan is particularly encouraging as both domestic and corporate demand look to have made a good start to 2005. The indications for Europe are more modest but early data for Germany, at least, suggest that improving investment demand and consumer spending should produce meaningful GDP growth in the first quarter. Nevertheless the main growth engines of the world economy remain the USA and China. US consumer and investment spending continued to grow strongly in February and the first quarter may see growth of about 4%. Data for China confirms a slight slowdown in the growth rates for retail sales in January and February but industrial production growth accelerated, rising to 16.9% year-on-year. There are risks on the sustainability of world economic growth in 2005. -

February 2016

OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report 10 February 2016 Feature article: Review and outlook of global demand Oil market highlights 1 Feature article 3 Crude oil price movements 5 Commodity markets 11 World economy 16 World oil demand 35 World oil supply 44 Product markets and refi nery operations 58 Tanker market 65 Oil trade 69 Stock movements 77 Balance of supply and demand 85 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Helferstorferstrasse 17, A-1010 Vienna, Austria E-mail: prid(at)opec.org Website: www.opec.org Oil market highlights Crude Oil Price Movements The OPEC Reference Basket (ORB) declined by around 21% to average $26.50/b in January. Ongoing excess supply, the weakening Chinese economy and lower seasonal heating demand continued to weigh on the market. Crude oil futures prices also declined significantly, with ICE Brent down $6.98 to average $31.93/b and Nymex WTI losing $5.67 to average $31.66/b. The Brent-WTI spread narrowed to just 15¢/b. World Economy World economic growth has been revised down to 2.9% for 2015 and 3.2% for 2016. OECD growth in 2016 has been revised lower to 2.0%, the same pace as in the previous year. In the emerging economies, China’s growth in 2016 has been revised down slightly to 6.3% while India’s growth has been revised lower to 7.5%. Meanwhile, increasing difficulties in both Brazil and Russia are seen pushing both economies into recession for the second consecutive year. World Oil Demand World oil demand growth in 2015 is expected to increase by 1.54 mb/d, unchanged from the previous report, to average 92.96 mb/d. -

Companies Involved in Oilfield Services from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Companies Involved in Oilfield Services From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Diversified Oilfield Services Companies These companies deal in a wide range of oilfield services, allowing them access to markets ranging from seismic imaging to deep water oil exploration. Schlumberger Halliburton Baker Weatherford International Oilfield Equipment Companies These companies build rigs and supply hardware for rig upgrades and oilfield operations. Yantai Jereh Petroleum Equipment&Technologies Co., Ltd. National-Oilwell Varco FMC Technologies Cameron Corporation Weir SPM Oil & Gas Zhongman Petroleum & Natural Gas Corpration LappinTech LLC Dresser-Rand Group Inc. Oilfield Services Disposal Companies These companies provide saltwater disposal and transportation services for Oil & Gas.. Frontier Oilfield Services Inc. (FOSI) Oil Exploration and Production Services Contractors These companies deal in seismic imaging technology for oil and gas exploration. ION Geophysical Corporation CGG Veritas Brigham Exploration Company OYO Geospace These firms contract drilling rigs to oil and gas companies for both exploration and production. Transocean Diamond Offshore Drilling Noble Hercules Offshore Parker Drilling Company Pride International ENSCO International Atwood Oceanics Union Drilling Nabors Industries Grey Wolf Pioneer Drilling Co Patterson-UTI Energy Helmerich & Payne Rowan Companies Oil and Gas Pipeline Companies These companies build onshore pipelines to transport oil and gas between cities, states, and countries. -

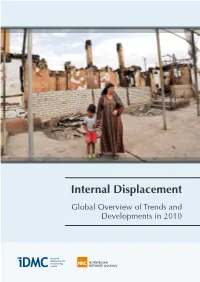

Internal Displacement Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2010 Internally Displaced People Worldwide December 2010

Internal Displacement Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2010 Internally displaced people worldwide December 2010 Turkey FYR Macedonia 954,000– Russian Federation Armenia Azerbaijan Uzbekistan Turkmenistan 650 1,201,000 6,500–78,000 At least 8,000 Up to About 3,400 Undetermined 593,000 Serbia Kyrgyzstan About About 75,000 225,000 Georgia Kosovo Up to Afghanistan 18,300 258,000 At least 352,000 Croatia 2,300 Bosnia and Herzegovina 113,400 Cyprus Pakistan Up to 208,000 At least 980,000 Israel Nepal Undetermined About 50,000 Occupied Palestinian Territory At least 160,000 India At least 650,000 Algeria Undetermined Chad Bangladesh 171,000 Undetermined Iraq Senegal 2,800,000 Laos 10,000–40,000 Undetermined Mexico Syria Sri Lanka About 120,000 Liberia At least At least Undetermined 327,000 The Philippines 433,000 At least 15,000 Côte d´Ivoire Lebanon Undetermined At least 76,000 Guatemala Togo Yemen Myanmar Undetermined Undetermined About 250,000 At least 446,000 Eritrea Indonesia Niger About 10,000 About 200,000 Timor-Leste Colombia Undetermined Undetermined 3,600,000–5,200,000 Ethiopia Nigeria About Undetermined CAR 300,000 192,000 Peru Sudan Somalia About 150,000 4,500,000– Republic of About 1,500,000 5,200,000 the Congo Kenya Up to 7,800 About 250,000 DRC Uganda About At least 166,000 1,700,000 Rwanda Undetermined Angola Burundi Undetermined Up to 100,000 Zimbabwe 570,000–1,000,000 Internal Displacement Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2010 March 2011 Children at the displace- ment camp of Karehe.