Online Communication Satisfaction in Using an Internet-Based Information Management System Among Employees at Four Research Universities in Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kuok Foundation Berhad (9641-T) Undergraduate Awards 2014 ( Private Universities / Colleges )

KUOK FOUNDATION BERHAD (9641-T) UNDERGRADUATE AWARDS 2014 ( PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES / COLLEGES ) KUOK FOUNDATION BERHAD invites applications for the above awards from Malaysian citizens applying for or currently pursuing full time undergraduate studies at the following institutions :- Private Universities AIMST University, Kedah Asia Pacific University of Technology and Innovation (APU), Kuala Lumpur HELP University, Kuala Lumpur International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur INTI International University, Laureate International Universities, Nilai Monash University Malaysia, Sunway Campus Multimedia University, Cyberjaya & Melaka Campus Nilai University, Nilai Sunway University, Bandar Sunway Taylor’s University, Subang Jaya University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, Semenyih UCSI University, Kuala Lumpur Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Perak / Sg. Long Campus Private University Colleges KDU University College, Petaling Jaya Tunku Abdul Rahman University College, Setapak Private Colleges INTI International College Subang, Subang Jaya KBU International College, Petaling Jaya Stamford College, Petaling Jaya Course Criteria (1) Undergraduate courses undertaken and completed in Malaysia only (including “3+0” foreign degree courses); (2) Accreditation by MQA (Course accreditation can be verified at MQR portal at the MQA website : www.mqa.gov.my); (3) Priority given to science stream courses. Type and Value of Award Loans or half-loan half-grants ranging from RM10,000 to RM30,000 per annum depending on courses undertaken. Eligibility (1) Malaysian Citizenship; (2) Genuine financial need and good academic results. Must possess relevant pre-university qualifications, eg. STPM or equivalent. Application forms can be downloaded from www.kuokfoundation.com or obtained from :- Kuok Foundation Berhad Undergraduate Awards (Private Universities / Colleges), Letter Box No. 110, 16th Floor UBN Tower, No. 10 Jalan P. -

No Nama IPTS Yang Diluluskan Oleh MQA FSI Network Sources From

Nama IPTS yang diluluskan oleh MQA No Nama IPTS yang diluluskan oleh MQA FSI Network Sources from http://www.lan.gov.my/eskp/iptslist.cfm 1 Institut Bina Usahawan (EDI Kuala Lumpur) - Tukar Nama 8/12/2004 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej Pengajian Strategik dan Teknologi (Kuala Lumpur)) 2 Institut Pendidikan Lanjutan Flamingo - Tukar Nama 2/2/05 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej Antarabangsa Flamingo) Yes 3 Ace College 4 AIMST University Yes 5 Akademi Bintang - Tukar Nama 20/9/2005 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej Antarabangsa Westminster) Yes 6 Akademi Digital Animasi dan Media Yes 7 Akademi HELP Yes 8 Akademi Hotel & Pelancongan ITTAR 9 Akademi IBBM 10 Akademi IMH 11 Akademi Infotech MARA 12 Akademi Jaringan Pemasaran 13 Akademi Kejururawatan Gleneagles 14 Akademi Kreatif 15 Akademi Kreatif ALIF - Tukar Nama 10/11/2005 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej ALFA) Yes 16 Akademi Latihan Penerbangan Asia Pacific 17 Akademi Laut Malaysia (ALAM Melaka) 18 Akademi Laut Malaysia (ALAM Terengganu) 19 Akademi Multimedia MTDC 20 Akademi Muzik SIM 21 Akademi Rekabentuk Komunikasi Pertama 22 Akademi Saito - Tukar Nama 3/9/2003 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej Saito) 23 Akademi Seni dan Muzik YAMAHA 24 Akademi Seni Komunikasi Baruvi - Tukar Nama 15/2/2008 (Nama Baru / New Name : Akademi Yes) 25 Akademi Seni Lukis Dasein 26 Akademi Teknologi Maklumat Global NIIT 27 Akademi Teknologi Park Malaysia (TPM Academy) - Tukar Nama 19/03/2007 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej Technology Park Malaysia) 28 Akademi Yes 29 Allianze College of Medical Science (Pulau Pinang) 30 Al-Madinah -

The Journal of Social Sciences Research ISSN(E): 2411-9458, ISSN(P): 2413-6670 Special Issue

The Journal of Social Sciences Research ISSN(e): 2411-9458, ISSN(p): 2413-6670 Special Issue. 2, pp: 800-806, 2018 Academic Research Publishing URL: https://arpgweb.com/journal/journal/7/special_issue Group DOI: https://doi.org/10.32861/jssr.spi2.800.806 Original Research Open Access The Perception of Malaysian Buddhist towards Islam in Malaysia Ahmad Faizuddin Ramli* PhD Candidate, Center for Akidah and Global Peace, Faculty of Islamic Studies, The National University of Malaysia / Lecturer at Department of Social Sciences, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Nilai University, Malaysia Jaffary Awang Assoc. Prof. Dr., Chairman, Center for Akidah and Global Peace, Faculty of Islamic Studies, The National University of Malaysia / Senior Fellow at The Institute of Islam Hadhari, The National University of Malaysia, Malaysia Abstract The existence of Muslim-Buddhist conflicts in the Southeast Asian region such as in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand is based on the perception that Islam is a threat to Buddhism. While in Malaysia, although the relationship between the Muslims and Buddhists remains in harmony, there is a certain perception among Buddhists towards Islam. Hence, this article will discuss the forms of Buddhism's perception of Islam in Malaysia. The study was qualitative using document analysis. The study found that particular group of Buddhists in Malaysia had a negative perception of Islam, particularly on the implementation of Islamization policy by the government and the Islamic resurgence movement in Malaysia. This perception is based on misunderstanding of Islam which is seen as a threat to the survival of Buddhists in practicing their teachings. The study recommends the empowerment of understanding between the religious adherents through Islamic-Buddhist dialogue at various levels of government and NGOs. -

Download Fair Directory

UTP-Sureworks-Directory-V5.pdf 1 13/11/2019 5:02:57 PM C M Y CM MY A CY CMY K 2019_ad_A-Levels_A5_Dec.indd 2 19/11/2019 3:09 PM Inside this fair directory MESSAGE CONTENTS ADVERTISERS in this directory 5 Welcome Message MESSAGE FROM 6-7 Which Pre-U Programme Should DATIN JERCY CHOO You Pursue? ACCA (The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants) 15 A Closer Look at Veterinary Science FROM SUREWORKS 12-13 AIMST University 14 Organiser of the Education & Further Studies Fair, Dec 2019 What is Automotive Engineering? Asia Pacific University 26 16-17 Curtin University 19 Skills to Prepare You for the Falcon Universal 10 20-21 Fourth Industrial Revolution HELP University IFC Kolej Yayasan UEM (KYUEM) 8 Welcome to the Education & Datin Jercy Choo 22-23 What are Green Jobs? Manipal International University CPS Further Studies Fair Series 50! Medic Ed Consultant Sdn Bhd IBC 28-29 Careers in Event Management Methodist College Kuala Lumpur OBC If you are currently searching for the next step to take in your education journey, you are in the Monash University Malaysia 18 right place! Find all the information you need right here at the fair over the weekend. As there are 32-33 Careers in Sports Science MyStudy Education Consulting so many education options available today, it is important to do as much research as possible to Sdn Bhd (Study Abroad) 35 ultimately choose the right course for you. 36-37 Jobs to Expect in 2020 New Era University College 27 Newcastle University The fair features leading universities, colleges, and skills-based institutions in Malaysia and abroad. -

How to Make the Most out of University

PROGRAMMES OFFERED PRE-U Pre-University Studies Pharmacy Foundation in Science Pharmacy Foundation in Business Dentistry Medicine and Biomedical Science Dental Technology Medical Laboratory Technology Dental Surgery (DDS) Biomedical Sciences IT IS TIME TO SET YOUR FUTURE Medicine & Surgery (MBBS) Nursing and Midwifery Nursing Health and Sport Sciences Midwifery WITH US Environmental Health Paediatric Nursing Medical Imaging Hospital Management Physiotherapy Health Care Practice Environmental Health and Safety Business, Finance and Engineering & Information S Hospitality S Technology Marketing Mechanical Engineering Restaurant Management Civil Engineering Hotel Management Electrical and Electronic Engineering Human Resource Management Accounting Business Administration PRE-U Islamic Finance WHAT’S AFTER SPM? 1-2 years ? Pre-U (A-Level, STPM, etc.) el v ? e L - Optional Scholarships O M / P for 2018 S 1 year 4 years Foundation Degree Employment Postgraduate Studies are You available Option 1: Option 2: now! Enter 2nd year of degree Straight to work 3 years Diploma 24 1800 88 0300 Follow us on: MAHSA University Bandar Saujana Putra Campus /MAHSAUniversity +603 5102 2200 Jalan SP 2, Bandar Saujana Putra, www.mahsa.edu.my /mahsauniversity [email protected] 42610 Jenjarom Selangor /MAHSAedu 4 Inside this fair directory Visit www.Sureworks.info for more information on courses and careers. 5 CONTENTS ADVERTISERS in this directory Message from 5 Welcome Message Datin Jercy Choo Which Pre-University Programme 6-7 Suits You? ACCA (The Association -

Social Media Monitoring Dashboard for University by Dicken Tan

SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY BY DICKEN TAN A REPORT SUBMITTED TO Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF COMPUTER SCIENCE (HONS) Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus) JAN 2020 UNIVERSITI TUNKU ABDUL RAHMAN REPORT STATUS DECLARATION FORM Title: SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY Academic Session: JAN 2020 I DICKEN TAN (CAPITAL LETTER) declare that I allow this Final Year Project Report to be kept in Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman Library subject to the regulations as follows: 1. The dissertation is a property of the Library. 2. The Library is allowed to make copies of this dissertation for academic purposes. Verified by, _________________________ _________________________ (Author’s signature) (Supervisor’s signature) Address: 146, JALAN PASIR PUTEH 31650 IPOH DR. PRADEEP ISAWASAN PERAK (Supervisor’s name) Date: 24 APRIL 2020 Date: 24 APRIL 2020 TITLE PAGE SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY BY DICKEN TAN A REPORT SUBMITTED TO Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF COMPUTER SCIENCE (HONS) Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus) JAN 2020 i DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this report entitled “SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY” is my own work except as cited in the references. The report has not been accepted for any degree and is not being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signature : _________________________ Name : DICKEN TAN Date : 24 APRIL 2020 BCS (Hons) Computer Science Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus), UTAR. -

Taylors Times

FOLLOW US APRIL 2013 | ISSUE #09 SPOTLIGHT ACHIEVEMENTS & RECOGNITION Promoting Youth A Stylish Way to Volunteerism @ ‘Jemore’ Clothes Taylor’s University A brilliant idea of making a Taylor’s University recently clothes hanger inspired by played host for the 1 Malaysia the vivid reminiscence of for Youth (iM4U) Reach Out traditional papan (wooden) Convention & Concert on March house won Taylor’s 2, 2013, which saw a huge turn- University’s student, Kok out of more than 3,000 youths. Wen Yee, the first prize… The convention and concert was READ MORE launched by Prime Minister, YAB Dato’ Sri Najib Tun Razak, whom called upon Malaysian ALUMNI FEATURES youths to give back to the community by actively taking Khoo Cai Lin – part in volunteerism activities, in his opening speech. National Swimmer If one is interested in sports, one must give it all out as it will not benefit anyone if things are being done half-heartedly… READ MORE READ MORE INDUSTRIAL TEACHING & LEARNING RESEARCH & ENGAGEMENT COMMERCIALISATION Building a Career New TCONSULT Inks with a Masters in Hospitality, First Partnership Communication Tourism and with Thiallan The National Higher Culinary Arts BioHerbs Education Strategic Plan School in Taylor’s Consultancy crafted by the Ministry of Desaru Coast Sdn Bhd (TCONSULT) Higher Education recently signed a Malaysians will soon (MOHE) emphasised Memorandum of be able to benefit that Malaysia needs to Understanding (MOU) from a partnership produce human capital with Thiallan Bioherbs between Destination with a first class mind Sdn Bhd, a company Resorts and Hotels set in order to face involved in the (DRH), established developmental manufacturing of by the Malaysian challenges in today’s vegetarian soft gelatin Government knowledge and (soft-gel) and health investment’s arm, innovation based products. -

Panel Institutes

PANEL INSTITUTES COUNTRY LOCATION AUSTRALIA Universities AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY CANBERRA UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE MELBOURNE MONASH UNIVERSITY MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES SYDNEY UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY SYDNEY UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA PERTH UNIVERSIT OF QUEENSLAND BRISBANE UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE ADELAIDE ATN (Australian Technology Network) Universities Curtin University of Technology Perth QUT ( Queensland University of Technology) Brisbane RMIT (Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology) Melbourne UniSA ( University of South Australia) Adelaide UTS ( University of Technology of Sydney ) Sydney Other Australian Unviersities Australian Catholic University Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane Bond University Brisbane Central Queensland University Melbourne, Sydney, Gold Coast, Rockhampton PANEL INSTITUTES Charles Sturt University Sydney Deakin University Melbourne ECU (Edith Cowan University) Perth Griffith University Brisbane, Gold Coast James Cook University Brisbane La Trobe University Melbourne, Bendigo Southern Cross University Lismore, Sydney Swinburne University of Technology Melbourne University of Ballarat University of Southern Queensland Sydney Toowoomba/Sydney Sydney University of Tasmania Hobart University of Western Sydney (UWS) Sydney VU ( Victoria University) Melbourne TAFE / Colleges: Australian School of Tourism & Hotel Management Perth Basair Aviation College - Australia Kaplan Business School Sydney Curtin International College Perth Holmes Institute Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane Holmesglen Institute of TAFE -

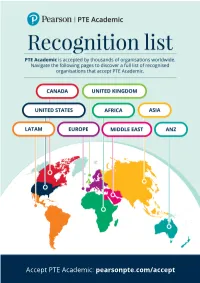

Global Recognition List August

Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept Africa Egypt • Global Academic Foundation - Hosting university of Hertfordshire • Misr University for Science & Technology Libya • International School Benghazi Nigeria • Stratford Academy Somalia • Admas University South Africa • University of Cape Town Uganda • College of Business & Development Studies Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept August 2021 Africa Technology & Technology • Abbey College Australia • Australian College of Sport & Australia • Abbott School of Business Fitness • Ability Education - Sydney • Australian College of Technology Australian Capital • Academies Australasia • Australian Department of • Academy of English Immigration and Border Protection Territory • Academy of Information • Australian Ideal College (AIC) • Australasian Osteopathic Technology • Australian Institute of Commerce Accreditation Council (AOAC) • Academy of Social Sciences and Language • Australian Capital Group (Capital • ACN - Australian Campus Network • Australian Institute of Music College) • Administrative Appeals Tribunal • Australian International College of • Australian National University • Advance English English (AICE) (ANU) • Alphacrucis College • Australian International High • Australian Nursing and Midwifery • Apex Institute of Education School Accreditation Council (ANMAC) • APM College of Business and • Australian Pacific College • Canberra Institute of Technology Communication • Australian Pilot Training Alliance • Canberra. Create your future - ACT • ARC - Accountants Resource -

Garis Panduan Permohonan Application Guideline

APPLICATION GUIDELINE/REQUIREMENT GARIS PANDUAN PERMOHONAN TERTIARY EDUCATION SPONSORSHIP PROGRAMME (TESP 2020) Open to all full-time student who are currently pursuing First Degree Programme at selected field and selected Local Higher Learning Institution. APPLICATIONS REQUIREMENTS • Application must be made online thru MARA Portal via: www.mara.gov.my starting 13th April 2020 (Monday) 10.00am until 4th May 2020 (Monday) 12.00pm. • Applicant must meet the general requirements and academic requirements. • If false information given by the applicant, MARA reserves the right to terminate or withdraw the loan offer. GENERAL REQUIREMENTS • Malaysian. • Applicant and either one parents is Bumipuera. • Meet the family Sosio Economy Status (SES) eligibility requirements set by MARA. • Parents total taxable income is not more than RM180,000 a year. If parents are self- employed or work at oversea, their average gross income must be less than RM 15,000 per month • Parents/Guardians and applicant are not blacklisted by MARA. • Applicant do not receive any financial support/sponsorship from any agency for current study programme (double sponsor). • Sponsorship is not given to applicant taking same programme level. • Free from any chronic/ contagious disease/ disease that require follow-up treatment. • Applicant age limit should not exceed 40 years old at the time of application. ACADEMIC REQUIREMENTS New Student • Obtain CGPA > 3.0 in Asasi/ Matriculation/ Persediaan/ STPM and equivalent. Existing Student • Obtain CGPA > 3.0 in previous semester; AND • Their balance study is not less than a year. Others • Pass SPM with credit Bahasa Melayu. • Academic requirement for medicine, dentistry and pharmacy programme must be meet the criteria set by professional board. -

Public Opinion of Regional Cooperation and the Formation of the Asean Community: a Comparative Study in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305992732 PUBLIC OPINION OF REGIONAL COOPERATION AND THE FORMATION OF THE ASEAN COMMUNITY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY IN MALAYSIA, INDONESIA AND SINGAPORE Thesis · July 2012 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.3671.3205 CITATIONS READS 0 270 1 author: Guido Benny Taylor's University 45 PUBLICATIONS 173 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Reflexive Stocktaking: IR Research and Teaching Trends in Southeast Asia View project Malaysian response and attitude toward Daesh/IS View project All content following this page was uploaded by Guido Benny on 08 August 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. PUBLIC OPINION OF REGIONAL COOPERATION AND THE FORMATION OF THE ASEAN COMMUNITY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY IN MALAYSIA, INDONESIA AND SINGAPORE GUIDO BENNY THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES UNIVERSITI KEBANGSAAN MALAYSIA BANGI 2012 PENDAPAT AWAM MENGENAI KERJASAMA SERANTAU DAN PENUBUHAN KOMUNITI ASEAN: KAJIAN PERBANDINGAN DI MALAYSIA, INDONESIA DAN SINGAPURA GUIDO BENNY THESIS YANG DIKEMUKAKAN UNTUK MEMPEROLEH IJAZAH DOKTOR FALSAFAH FAKULTI SAINS SOSIAL DAN KEMANUSIAAN UNIVERSITI KEBANGSAAN MALAYSIA BANGI 2012 11 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the work in this dissertation is my own except for quotations and summaries which have been duly acknowledged. 13 December 2012 GUIDO BENNY P48998 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Such a conducive community enable me to complete my doctoral dissertation. Many people advised, supported, and encourage me throughout the process of writing. First of all, I had an amazing dissertation committee, which include Prof. -

Bwlxhvbjyw5y5ytux3bjjhuqz

FAOL_A5 Flyer.pdf 1 11/07/2019 4:25 PM C M Y CM Foundation Foundation MY CY in Arts in Science CMY K Receive a 100% Bursary* for your Foundation Programme when you join our Foundation-Degree Pathway! Intake: September 2019 • Foundation in Arts – available in Damansara Heights and Subang 2 campuses • Foundation in Science – available in Damansara Heights campus *Terms and Conditions Apply. FOUNDATION IN ARTS: KPT/JPS (R2/010/3/0224) (A10668) 07/24 KPT/JPS (R2/010/3/0225) (A10667) 07/24 603- 2716 2000 www.help.edu.my facebook.com/HELPUniversity HELP University Sdn Bhd No. 15, Jalan Sri Semantan 1, Off Jalan Semantan, Bukit Damansara, 50490 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia JPT/BPP(D)1000-701/507 DU028(W) 2019_ad_HMC_A5_color2.indd 1 05/07/2019 12:18 PM “Perdana University Graduate School of Medicine (PUGSOM)’s emphasis on research prepares you to excel as a clinician later.” – Alvin Lee (Doctor of Medicine, 2017 Intake) The course modules are more in depth compared to Foundation courses in other universities.” - Diviya Eswary (Foundation in Science, 2018 Intake) “Perdana University is leading the bioinformatics effort in the country.” – Siti Safura Jaapar (Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Intake) “A globally recognized medical curriculum tailored for a local setting.” – Rajwin Raja (PU-RCSI Medical Degree Programme, 2018 Alumni) “All my lecturers were very enthusiastic and experienced in their field and the C curriculum were holistic enough to prepare me to be a competent occupational therapist.” M – Nur Nadirah binti Ruzaimi (BSc (Hons) in Occupational