Analysis of Chinese Investments in Non-Forest Environment Affecting the Forest Land-Use in Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cahiers Du BUCREP Volume 01, Numéro 01

Cahiers du BUCREP Volume 01, Numéro 01 Analyses préliminaires des données communautaires dans la Province du sud Cameroun en 2003 Tome 1 Analyses Bureau Central des Recensements Juin 2008 et des Etudes de Population - BUCREP 1 Cahiers du BUCREPvolume 01,numéro 01 DIRECTEUR DE PUBLICATION Madame Bernadette MBARGA, Directeur Général CONSEILLE EDITORIAL Monsieur ABDOULAYE OUMAROU DALIL, Directeur Général Adjoint Monsieur Raphaël MFOULOU, Conseiller Technique Principal - UNFPA / 3ème RGPH COORDONNATEUR TECHNIQUE YOUANA Jean PUBLICATION MBARGA MIMBOE EQUIPE DE REDACTION DE CE TOME Joseph-Blaise DJOUMESSI, Gérard MEVA’A, Ambroise HAKOUA, Pascal MEKONTCHOU, André MIENGUE, Mme Marthe ONANA, Martin TSAFACK, P. Kisito BELINGA, Hervé Joël EFON, Jules Valère MINYA, Lucien FOUNGA COLLABORATION DISTRIBUTION Cellule de la Communication et des Relations Publiques Imprimerie Presses du BUCREP 2 Analyses préliminaires des données communautaires dans la province du SUD CAMEROUN en 2003 SOMMAIRE UNE NOUVELLE SOURCE DE DONNEES 5 METHODOLOGIE DES TRAVAUX CARTOGRAPHIQUES 7 1- PRODUCTIONS DU VILLAGE 8 2- INFRASTRUCTURES SCOLAIRES 12 3- INFRASTRUCTURES SANITAIRES 18 4- INFRASTRUCTURES SOCIOCULTURELLES 23 5- CENTRES D’ETAT CIVIL 25 6- AUTRES INFRASTRUCTURES 29 7- INFRASTRUCTURES TOURISTIQUES 31 8- RESEAU DE DISTRIBUTION D’EAU ET D’ELECTRICITE 36 9- VIE ASSOCIATIVE 39 3 4 Analyses préliminaires des données communautaires dans la province du SUD CAMEROUN en 2003 UNE NOUVELLE SOURCE DE DONNNEES : LE QUESTIONNAIRE LOCALITE Les travaux de cartographie censitaire déjà -

Étude D'impact Environnemental Et Social

FONDS AFRICAIN DE DÉVELOPPEMENT DÉPARTEMENT DE L’INFRASTRUCTURE RÉPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN CAMEROUN : ROUTE SANGMÉLIMA-FRONTIERE DU CONGO ÉTUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL Aff : 09-01 Avril 2009 Etude d'impact environnemental et social de la route Sangmelima‐frontière du Congo Page i TABLE DES MATIERES I ‐ INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 I.1 ‐Contexte et justification de ce projet d’aménagement routier ....................................................... 1 I.1.1 ‐ Une vue d’ensemble du projet ................................................................................................................. 1 I.1.2 ‐ La justification du projet .......................................................................................................................... 3 I.2 ‐Objectifs de la présente étude ......................................................................................................... 4 I.3 ‐Méthodologie suivie pour la réalisation de l’étude ......................................................................... 5 I.3.1 – La collecte des données sur les enjeux du milieu récepteur .................................................................... 5 I.3.2 – L’analyse des impacts et la proposition d’un PGEIS du projet ................................................................ 6 I.4 ‐Structure du rapport ....................................................................................................................... -

De 45 Adjoints D'administration

AO/CBGI REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix –Travail – Patrie Peace – Work – Fatherland -------------- --------------- MINISTERE DE LA FONCTION PUBLIQUE MINISTRY OF THE PUBLIC SERVICE ET DE LA REFORME ADMINISTRATIVE AND ADMINISTRATIVE REFORM --------------- --------------- SECRETARIAT GENERAL SECRETARIAT GENERAL --------------- --------------- DIRECTION DU DEVELOPPEMENT DEPARTMENT OF STATE HUMAN DES RESSOURCES HUMAINES DE L’ETAT RESSOURCES DEVELOPMENT --------------- --------------- SOUS-DIRECTION DES CONCOURS SUB DEPARTMENT OF EXAMINATIONS ------------------ -------------------- CONCOURS DIRECT POUR LE RECRUTEMENT DE 45 ADJOINTS D’ADMINISTRATION SESSION 2020 CENTRE D’EBOLOWA LISTE DES CANDIDATS AUTORISÉS À SUBIR LES ÉPREUVES ÉCRITES DU 12 SEPTEMBRE 2020 RÉGION DÉPARTEMENT NO MATRICULE NOMS ET PRÉNOMS DATE ET LIEU DE NAISSANCE SEXE LANGUE D’ORIGINE D’ORIGINE 1. AAL4428 ABESSOLO BELINGA MARQUISE 07/07/1998 A EBOLOWA F SU MVILA F 2. AAL1019 ABOMO MINKOULOU MONIQUE AURELIE 28/12/1992 A BENGBIS F SU DJA ET LOBO F 3. AAL5292 ABOSSSOLO MARTHE BRINDA 15/12/2000 A EBOLOWA F SU MVILA F 4. AAL3243 ABOUTOU MEBA CAROLE DEBORA 03/06/1996 A SANGMELIMA F SU DJA ET LOBO F 5. AAL2622 ADA MBEA CHRISTELLE FALONNE 10/06/1995 A MENDJIMI F SU VALLEE DU NTEM F 6. AAL1487 ADJOMO OBAME JOSSELINE 28/08/1993 A YAOUNDE F SU DJA ET LOBO F 7. AAL3807 AFA'A POMBA VALERE GHISLAIN 28/04/1997 A AWAE M SU DJA ET LOBO F 8. AAL4597 AFANE BERTHOLD 15/11/1998 A KONGO-NDONG M SU DJA ET LOBO F MINFOPRA/SG/DDRHE/SDC|Liste générale des candidats Adjoints d’Administration, session 2020_Ebolowa Page 1 9. AAL4787 AFANE MALORY 27/05/1999 A MBILEMVOM F SU DJA ET LOBO F 10. -

A Companion Journal to Forest Ecology and Management and L

84 Volume 84 November 2017 ISSN 1389-9341 Volume 84 , November 2017 Forest Policy and Economics Policy Forest Vol. CONTENTS Abstracted / indexed in: Biological Abstracts, Biological & Agricultural Index, Current Advances in Ecological Science, Current Awareness in Biological Sciences, Current Contents AB & ES, Ecological Abstracts, EMBiology, Environment Abstracts, Environmental Bibliography, Forestry Abstracts, Geo Abstracts, GEOBASE, Referativnyi Zhurnal. Also covered in the abstract and citation database Scopus®. Full text available on ScienceDirect®. Special Issue: Forest, Food, and Livelihoods Guest Editors: Laura V. Rasmussen, Cristy Watkins and Arun Agrawal Forest contributions to livelihoods in changing Forest ecosystem services derived by smallholder agriculture-forest landscapes farmers in northwestern Madagascar: Storm hazard L.V. Rasmussen , C. Watkins and A. Agrawal (USA) 1 mitigation and participation in forest management An editorial from the handling editor R. Dave , E.L. Tompkins and K. Schreckenberg (UK) 72 S.J. Chang (United States) 9 A methodological approach for assessing cross-site 84 ( Opportunities for making the invisible visible: Towards landscape change: Understanding socio-ecological 2017 an improved understanding of the economic systems ) contributions of NTFPs T. Sunderland (Indonesia, Australia), R. Abdoulaye 1–120 C.B. Wahlén (Uganda) 11 (Indonesia), R. Ahammad (Australia), S. Asaha Measuring forest and wild product contributions to (Cameroon), F. Baudron (Ethiopia), E. Deakin household welfare: Testing a scalable household (New Zealand), J.-Y. Duriaux (Ethiopia), I. Eddy survey instrument in Indonesia (Canada), S. Foli (Indonesia, The Netherlands), R.K. Bakkegaard (Denmark), N.J. Hogarth (Finland), D. Gumbo (Indonesia), K. Khatun (Spain), I.W. Bong (Indonesia), A.S. Bosselmann (Denmark) M. Kondwani (Indonesia), M. Kshatriya (Kenya), and S. -

Resolving Land-Related Conflicts Through Dialogue: Lessons from The

Resolving land-related conflicts through dialogue: Lessons from the outskirts of a protected area in Cameroon Michelle Sonkoue, Romuald Ngono and Anna Bolin Legal tools for citizen empowerment Around the world, citizens’ groups are taking action to change the way investment in natural resources is happening and to protect rights and the environment for a fairer and more sustainable world. IIED’s Legal Tools for Citizen Empowerment initiative develops analysis, tests approaches, documents lessons and shares tools and tactics amongst practitioners (www.iied.org/legal-tools). The Legal Tools for Citizen Empowerment series provides an avenue for practitioners to share lessons from their innovative approaches to claim rights. This ranges from grassroots action and engaging in legal reform, to mobilising international human rights bodies and making use of grievance mechanisms, through to scrutinising international investment treaties, contracts and arbitration. This paper is one of a number of reports by practitioners on their lessons from such approaches. Other reports can be downloaded from www.iied.org/pubs and include: • Rebalancing power in global food chains through a “Ways of Working” approach: an experience from Kenya. 2019. Kariuki, E and Kambo, M • A stronger voice for women in local land governance: effective approaches in Tanzania, Ghana and Senegal. 2019. Sutz, P et al. • Improving accountability in agricultural investments: Reflections from legal empowerment initiatives in West Africa. 2017. Cotula, L and Berger, T (eds.) • Advancing indigenous peoples’ rights through regional human rights systems: The case of Paraguay. 2017. Mendieta Miranda, M. and Cabello Alonso, J • Connected and changing: An open data web platform to track land conflict in Myanmar. -

Protecting and Encouraging Customary Use of Biological

Forest Peoples Programme Protecting and encouraging customary use of biological resources by the Baka in the west of the Dja Biosphere Reserve Contribution to the implementation of Article 10(c) of the Convention on Biological Diversity Belmond Tchoumba and John Nelson with the collaboration of Georges Thierry Handja, Stephen Nounah, Emmanuel Minsolo and Bitoto Gilbert Mokomo Dieudonné Abacha Samuel Djala Luc Movombo Benjamin Alengue Ndengue Djampene Pierre Ndo Joseph Assing Didier Etong Mustapha Ndolo Samuel Claver Evina Reymondi Nsimba Josue Ati Majinot Mama Jean-Bosco Onanas Thomas Atyi Jean-Marie Megata François Sala Mefe Sylvestre Biango Felix Megolo Ze Thierry Protecting and encouraging customary use of biological resources by the Baka in the west of the Dja Biosphere Reserve Contribution to the implementation of Article 10(c) of the Convention on Biological Diversity Belmond Tchoumba and John Nelson with the collaboration of: Georges Thierry Handja, Stephen Nounah, Emmanuel Minsolo and Abacha Samuel Mama Jean-Bosco Alengue Ndengue Megata François Assing Didier Claver Megolo Bonaventure Ati Majinot Mokomo Dieudonné Atyi Jean-Marie Movombo Benjamin Biango Felix Ndo Joseph Bissiang Martin Ndolo Samuel Bitoto Gilbert Nsimba Josue Djala Luc Onanas Thomas Djampene Pierre Sala Mefe Sylvestre Etong Mustapha Ze Thierry Evina Reymondi This project was carried out with the generous support of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGIS) and the Novib-Hivos Biodiversity Fund © Forest Peoples Programme & Centre pour l’Environnement et le Développement -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

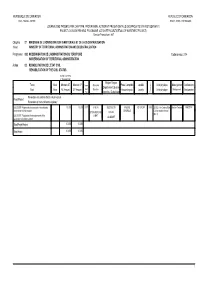

DETAILS DES PROJETS D'investissement) PROJECT LOG-BOOK PER HEAD, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJECT(DETAILS of INVESTMENT PROJECT) Exercice/ Financial Year : 2017

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX - TRAVAIL - PATRIE PEACE - WORK - FATHERLAND JOURNAL DES PROJETS PAR CHAPITRE, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJET (DETAILS DES PROJETS D'INVESTISSEMENT) PROJECT LOG-BOOK PER HEAD, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJECT(DETAILS OF INVESTMENT PROJECT) Exercice/ Financial year : 2017 Chapitre 07 MINISTERE DE L'ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION Head MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION AND DECENTRALIZATION Programme 092 MODERNISATION DE L'ADMINISTRATION DU TERRITOIRE Code service: 2004 MODERNISATION OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION Action 02 REHABILITATION DE L’ETAT CIVIL REHABILITATION OF THE CIVIL STATUS En Milliers de FCFA In Thousand CFAF Région/ Region Tache Num Montant AE Montant CP Année Structure Poste Comptable Localité Unité physique Mode gestion Gestionnaire Département/ Division Task Num AE Amount CP Amount Start Structure Accounting sta. Locality Unité physique Management Gestionnaire Year Arrondiss./ Sub-division Paragraphe Rénovation des centres d'état civil principaux Projet/Project Renovation of main civil status registery LOLODORF: Règlement des travaux de rénovation du 10 200 10 200 2017 34 00 20 SUD/ SOUTH PAIERIE LOLODORF 2230 223022 - Un Centre d'Etat Gestion Centrale MINISTRE centre d'état civil secondaire GENERALE Civil secondaire rénové DTION RESS FIN OCEAN [Qté:1] LOLODORF: Regulation of renovation work of the & MAT LOLODORF secondary civil status registery Total Projet/Project 10 200 10 200 Total Action 10 200 10 200 1 REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON -

CAC Au Niveau Communal Exercice 2003

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Paix-Travail-Patrie Source: FEICOM Yaoundé; le 05/09/2008 CAC au Niveau Communal Exercice 2003 - 2007 en francs CFA Commune 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Total BABESSI 71111420 73201803 52839330 78037678 82768880 357959111 BAFANG 61760230 63575727 45890930 67482231 71884728 310593846 BANKIM 0 0 0 0 0 0 BIBEY 6765501 6964379 5027105 7248353 7874585 33879923 BOKITO 64559463 66457245 47970899 70858006 75142845 324988458 DEUK 16553708 17040319 12300230 18042230 19267397 83203884 DOUALA 1240829221 1639118161 1438080202 2305592049 2523691305 9147310938 DOUALA 5 EME 0 0 0 0 0 0 DOUALA 3 EME 0 0 0 0 0 0 DOUALA 4 EME 0 0 0 0 0 0 ELIG-MFOMO 39728901 40896766 29520554 43767102 46241750 200155073 LEMBE 12415282 12780239 9225172 13585920 14450547 62457160 MBANDJOCK 27406319 67851363 59934264 95904105 130162475 381258526 MFOU 47912880 49599257 35802281 53029037 56081610 242425065 MINTA 16386455 16868211 12175998 17993653 19072796 82497113 NIETE 28141305 108247365 62400084 97220744 131017946 427027444 NKOLMETET 33107416 34080639 24600462 36472585 38534791 166795893 SANGMELIMA 38505581 39637486 28611567 41952802 53638511 202345947 TIBATI 77079032 79344838 57273564 84570425 89714776 387982635 YAOUNDE 755180462 1022432633 897031197 1429940622 1569420934 5674005848 YAOUNDE 1 ER 0 0 0 0 0 0 YAOUNDE 4 EME 0 0 0 0 0 0 YAOUNDE 7 EME 0 0 0 0 0 0 ABONG-MBANG 41384271 42600798 30750577 44977207 48168490 207881343 AFANLOUM 4068902 4188500 3023397 4482480 4735926 20499205 AKO 57010971 58686860 42361995 62612861 66356912 287029599 AKOEMAN 14898338 -

Cameroon Periodic Report 2010

United Nations E/C.12/CMR/2-3 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 19 July 2010 English Original: French Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Combined second and third periodic reports submitted by States parties under articles 16 and 17 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Cameroon *, ** [26 November 2008] * In accordance with the information transmitted to States parties regarding the processing of their reports, the present document was not edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. ** Annexes are available for consultation from the secretariat. GE.10-43750 (EXT) E/C.12/CMR/2-3 Contents Paragraphs Page Acronyms and abbreviations............................................................................................................ 3 I. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1−8 7 II. General presentation of the legal framework for the protection and promotion of human rights in Cameroon.................................................................................. 9−40 8 A. Normative framework..................................................................................... 11−19 8 B. Institutional framework................................................................................... 20−40 12 III. Government-encouraged processes for a closer regulation of economic, social and -

Plan Communal De Développement De Meyomessala Commune De

Plan Communal de développement de Meyomessala SOMMAIRE RESUME ............................................................................................................................... 4 LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ................................................................................................. 6 LISTE DES PHOTOS ............................................................................................................ 9 LISTE DES CARTES............................................................................................................10 LISTE DES ANNEXES .........................................................................................................12 1. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................13 1.1 Contexte et justification ...............................................................................................14 1.2 Objectifs du PCD ........................................................................................................15 1.3 Structure du PCD .......................................................................................................15 2. METHODOLOGIE ........................................................................................................16 2.1 Préparation de l’ensemble du processus...............................................................17 2.2 Collecte des informations et traitement .......................................................................18 2.3 -

Draft Final Report Icam Cameroon May 2011

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURE PROTECTION (MINEP) FFINALINAL DRAFT REPORT MAIN TEXT THE IMPLEMENTATION OF INTEGRATED COASTAL MANAGEMENT ((ICM)ICM) FOR THE KRIBIKRIBI---- CAMPO AREA IN CAMEROON Presented by: Environment and Resource Protection Cameroon May 2011 Draft final Report Project GP/RAF/04 on the implementation of the ICZM for the Kribi-Campo Area in Cameroon Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENT LIST OF ACRONYMS ………………………………………………. 8 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY …………………………………………… 11 CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION …………………………………….. 14 1.1 INTEGRATED COASTAL AREA MANAGEMENT APPROACH ……………………… 14 1.2 CONTEXT OF INTEGRATED COASTAL AREA MANAGEMENT WITHIN THE KRIBI CAMPO AREA ………………………………………………………………………………… 16 1.3 OBJECTIVE …………………………………………………………………………… 17 1.4 TASKS TO BE PERFORMED BY ENVI- REP CAMEROON ……………………………… 17 CHAPTER II: INSTITUTIONAL AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORK RELATED TO THE KRIBI CAMPO COASTAL ZONE SUSTAINABLE 19 DEVELOPMENT2.1 BACKGROUND AND C ONTEXT KRIBI………………………………………………………….. CAMPO COAST AL ZONE 19 2.2 INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR SUSTAINABLE COASTAL ZONE MANAGEMENT IN CAMEROON …………………………………………………………………………... 24 2.2.1 Key Institutional tools …………………………………………………………………. 24 2.2.2 Ocean Division Development Authority (MEAO)…………………………………….. 27 2.2.3 Other Local Institutions and bodies involved in coastal zone management………….... 28 2.2.4 Institutional arrangement for successful implementation of the integrated management for the Kribi Campo Coastal Area in Cameroon………………………... 29 2.2.5 Establishment of a Project Steering Committee (PSC)………………………………… 31 2.2.6 Role and responsibility of each stakeholder …………………………………………... 33 2.3 REGULATORY FRAMEWORK …………………………………………………….. 33 2.3.1 General regulatory framework for the sustainable coastal development ……………… 33 CHAPTER III: NATURAL ENVIRONMENT OF THE KRIBI CAMPO COASTAL ZONE ……………………………………………………………………………… 40 3.1 DEFINITION OF THE COASTAL ZONE BOUNDARIES …………………………………….... 40 3.2 DELIMITATION OF THE PROJECT AREA ………………………………………………….