A Companion Journal to Forest Ecology and Management and L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 13 SOUTHERN AFRICA

Chapter 13 Zimbabwe Chapter 13 SOUTHERN AFRICA: ZIMBABWE Taxonomic Inventory Taxa and life stages consumed Coleoptera Buprestidae (metallic woodborers) Sternocera funebris (author?), adult Sternocera orissa Buquet, adult Scarabaeidae (scarab beetles) Lepidiota (= Eulepida) anatine (author?), adult Lepidiota (= Eulepida) masnona (author?), adult Lepidiota (= Eulepida)nitidicollis (author?), adult Miscellaneous Coleoptera Scientific name(s) unreported Hemiptera Pentatomidae (stink bugs) Euchosternum (= Haplosterna; = Encosternum) delegorguei (Spinola) (= delagorguei), adult Pentascelis remipes (author?), adult Pentascelis wahlbergi (author?), adult Miscellaneous Hemiptera Scientific name(s) unreported Homoptera Cicadidae (cicadas) Loba leopardina (author?) Hymenoptera Apidae (honey bees) Trigona spp., larvae Formicidae (ants) Carebara vidua Sm., winged adult Isoptera Termitidae Macrotermes falciger Gerstacker (= goliath), winged adult, soldier, queen Macrotermes natalensis Haviland Lepidoptera Lasiocampidae (eggar moths, lappets) Lasiocampid sp., larva Limacodidae (slug caterpillars) Limacodid sp. Notodontidae (prominents) Anaphe panda (Boisdv.), larva Saturniidae (giant silkworm moths) Bunaea (= Bunea) alcinoe (Stoll), larva Bunaea sp., larva Cirina forda (Westwood), larva 1 of 12 9/20/2012 2:02 PM Chapter 13 Zimbabwe Gonimbrasia belina Westwood, larva Goodia kuntzei Dewitz (?), larva Gynanisa sp. (?), larva Imbrasia epimethea Drury, larva Imbrasia ertli Rebel, larva Lobobunaea sp., larva Microgone sp., (?), larva Pseudobunaea sp. (?), -

Étude D'impact Environnemental Et Social

FONDS AFRICAIN DE DÉVELOPPEMENT DÉPARTEMENT DE L’INFRASTRUCTURE RÉPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN CAMEROUN : ROUTE SANGMÉLIMA-FRONTIERE DU CONGO ÉTUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL Aff : 09-01 Avril 2009 Etude d'impact environnemental et social de la route Sangmelima‐frontière du Congo Page i TABLE DES MATIERES I ‐ INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 I.1 ‐Contexte et justification de ce projet d’aménagement routier ....................................................... 1 I.1.1 ‐ Une vue d’ensemble du projet ................................................................................................................. 1 I.1.2 ‐ La justification du projet .......................................................................................................................... 3 I.2 ‐Objectifs de la présente étude ......................................................................................................... 4 I.3 ‐Méthodologie suivie pour la réalisation de l’étude ......................................................................... 5 I.3.1 – La collecte des données sur les enjeux du milieu récepteur .................................................................... 5 I.3.2 – L’analyse des impacts et la proposition d’un PGEIS du projet ................................................................ 6 I.4 ‐Structure du rapport ....................................................................................................................... -

Traditional Consumption of and Rearing Edible Insects in Africa, Asia and Europe

Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition ISSN: 1040-8398 (Print) 1549-7852 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/bfsn20 Traditional consumption of and rearing edible insects in Africa, Asia and Europe Dele Raheem, Conrado Carrascosa, Oluwatoyin Bolanle Oluwole, Maaike Nieuwland, Ariana Saraiva, Rafael Millán & António Raposo To cite this article: Dele Raheem, Conrado Carrascosa, Oluwatoyin Bolanle Oluwole, Maaike Nieuwland, Ariana Saraiva, Rafael Millán & António Raposo (2018): Traditional consumption of and rearing edible insects in Africa, Asia and Europe, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1440191 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2018.1440191 Accepted author version posted online: 15 Feb 2018. Published online: 15 Mar 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 90 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=bfsn20 CRITICAL REVIEWS IN FOOD SCIENCE AND NUTRITION https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2018.1440191 Traditional consumption of and rearing edible insects in Africa, Asia and Europe Dele Raheema,b, Conrado Carrascosac, Oluwatoyin Bolanle Oluwoled, Maaike Nieuwlande, Ariana Saraivaf, Rafael Millanc, and Antonio Raposog aDepartment for Management of Science and Technology Development, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; bFaculty of Applied Sciences, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; -

Resolving Land-Related Conflicts Through Dialogue: Lessons from The

Resolving land-related conflicts through dialogue: Lessons from the outskirts of a protected area in Cameroon Michelle Sonkoue, Romuald Ngono and Anna Bolin Legal tools for citizen empowerment Around the world, citizens’ groups are taking action to change the way investment in natural resources is happening and to protect rights and the environment for a fairer and more sustainable world. IIED’s Legal Tools for Citizen Empowerment initiative develops analysis, tests approaches, documents lessons and shares tools and tactics amongst practitioners (www.iied.org/legal-tools). The Legal Tools for Citizen Empowerment series provides an avenue for practitioners to share lessons from their innovative approaches to claim rights. This ranges from grassroots action and engaging in legal reform, to mobilising international human rights bodies and making use of grievance mechanisms, through to scrutinising international investment treaties, contracts and arbitration. This paper is one of a number of reports by practitioners on their lessons from such approaches. Other reports can be downloaded from www.iied.org/pubs and include: • Rebalancing power in global food chains through a “Ways of Working” approach: an experience from Kenya. 2019. Kariuki, E and Kambo, M • A stronger voice for women in local land governance: effective approaches in Tanzania, Ghana and Senegal. 2019. Sutz, P et al. • Improving accountability in agricultural investments: Reflections from legal empowerment initiatives in West Africa. 2017. Cotula, L and Berger, T (eds.) • Advancing indigenous peoples’ rights through regional human rights systems: The case of Paraguay. 2017. Mendieta Miranda, M. and Cabello Alonso, J • Connected and changing: An open data web platform to track land conflict in Myanmar. -

Geo-Eco-Trop., 2014, 38, 2 : 339-372

Geo-Eco-Trop., 2014, 38, 2 : 339-372 Human consumption of Lepidoptera in Africa : an updated chronological list of references (370 quoted!) with their ethnozoological analysis La consommation humaine de Lépidoptères en Afrique : une liste chronologique actualisée des références (370 citées !) avec leur analyse ethnozoologique François MALAISSE1 & Paul LATHAM2 Résumé : La consommation humaine d’insectes ou “lépideroptérophagie” connaît un intérêt croissant. Dans le présent article 370 références abordant ce thème pour l’Afrique sont citées. Des accès à cette information par ordre chronologique ainsi que par ordre alphabétique des noms d’auteurs sont fournies. Une liste systématique des noms scientifiques des espèces consommées en Afrique est encore établie. L’importance de l’information disponible pour divers groupes ethnolinguistiques est signalée. L’évolution des thèmes approchés est analysée et commentée. Mots clés: Consommation, Lépidoptères, Afrique, Campéophagie. Abstract : Human consumption of insects or « lepidopterophagy » is becoming increasingly important. In the present paper 370 references dealing with this subject in Africa are quoted. Access to this information is provided both, by chronological and alphabetic order of authors. A systematic list of scientific names of edible Lepidoptera in Africa is also provided. The importance of the information available for various ethnolinguidstic groups is presented. The evolution of issues covered is analyzed and discussed. Keywords : Consumption, Lepidoptera, Africa, Campeophagy. INTRODUCTION The utilization of insects as a sustainable and secure source of animal-based food for the human diet has continued to increase in popularity in recent years (SHOCKLEY & DOSSEY, 2014). In particular, human consumption of Lepidoptera receives an increasing interest (MALAISSE et al., 2015). Several terms have been suggested to describe this consumption, notably regarding caterpillars, “campeophagy” (MALAISSE, 2002, 2004; MALAISSE et al. -

Protecting and Encouraging Customary Use of Biological

Forest Peoples Programme Protecting and encouraging customary use of biological resources by the Baka in the west of the Dja Biosphere Reserve Contribution to the implementation of Article 10(c) of the Convention on Biological Diversity Belmond Tchoumba and John Nelson with the collaboration of Georges Thierry Handja, Stephen Nounah, Emmanuel Minsolo and Bitoto Gilbert Mokomo Dieudonné Abacha Samuel Djala Luc Movombo Benjamin Alengue Ndengue Djampene Pierre Ndo Joseph Assing Didier Etong Mustapha Ndolo Samuel Claver Evina Reymondi Nsimba Josue Ati Majinot Mama Jean-Bosco Onanas Thomas Atyi Jean-Marie Megata François Sala Mefe Sylvestre Biango Felix Megolo Ze Thierry Protecting and encouraging customary use of biological resources by the Baka in the west of the Dja Biosphere Reserve Contribution to the implementation of Article 10(c) of the Convention on Biological Diversity Belmond Tchoumba and John Nelson with the collaboration of: Georges Thierry Handja, Stephen Nounah, Emmanuel Minsolo and Abacha Samuel Mama Jean-Bosco Alengue Ndengue Megata François Assing Didier Claver Megolo Bonaventure Ati Majinot Mokomo Dieudonné Atyi Jean-Marie Movombo Benjamin Biango Felix Ndo Joseph Bissiang Martin Ndolo Samuel Bitoto Gilbert Nsimba Josue Djala Luc Onanas Thomas Djampene Pierre Sala Mefe Sylvestre Etong Mustapha Ze Thierry Evina Reymondi This project was carried out with the generous support of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGIS) and the Novib-Hivos Biodiversity Fund © Forest Peoples Programme & Centre pour l’Environnement et le Développement -

7. Insects As Animal Feed

89 7. Insects as animal feed 7.1 OVErviEW In 2011, combined world feed production was estimated at 870 million tonnes, with revenue from global commercial feed manufacturing generating approximately US$350 billion globally. FAO estimates that production will have to increase by 70 percent to be able to feed the world in 2050, with meat outputs (poultry, pork and beef) expected to double (IFIF, 2012). Despite this, little has been said about the opportunities insects offer as feed sources (Box 7.1). At present, ingredients for both animal and fish feed include fishmeal, fish oil, soybeans and several other grains. A major constraint to further development are the prohibitive costs of feed, including meat meal, fishmeal and soybean meal, which represent 60–70 percent of production costs. Another problem is manure disposal, which is becoming a serious environmental problem; it is not uncommon for large amounts of manure to be stockpiled in open-air lots, swarming with flies. BOX 7.1 International Feed Industry Federation and FAO: looking for new, safe proteins The International Feed Industry Federation (IFIF) is a global organization mandated to play a coordinating role in promoting the sustainable supply of safe, healthy feed in the global feed industry. Its function is fundamentally important in developing countries, especially where national feed associations and sectors are weak or non-existent. In the late 1990s, the IFIF received Codex Alimentarius non-governmental organization (NGO) status, which was a first step towards improving the ways in which government regulates the industry. During this time, the IFIF began developing a close working relationship with FAO. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

Contribution Des Insectes De La Forêt Á La Sécurité

Produits forestiers non ligneux Document de TravailTravail N° 11 DEPARTEMENT DES FORETS CONTRIBUTION DESDES INSECTESINSECTES DE LA FORÉTFORET ÀA LA LA SÉCURITÉSECURITE ALIMENTAIRE L'EXEMPLE DESDES CHENILLES D'AFRIQUE CENTRALE 2004 PROGRAMME DESDES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX CONTRIBUTION DES INSECTES DE LALA FoRETFORÉT ... ~ ~ ÀA LA SECURITESÉCURITÉ ALIMENTAIRE L'EXEMPLE DESDES CHENILLESCHENILLES D'AFRIQUED' AFRIQUE CENTRALE Par Michel Philippe Balinga Paul Monzambe Mapunzu Jean-Baptiste MoussaMoussa Georges N'gasse 2004 Ce document est leIe premier numéronumero d'une sérieserie de documents de travail sur les produits forestiers non ligneux produits par leIe Programme des produits forestiers non ligneux. L'objectif de ces documents de travailtravail estest dede foumirfournir desdes informationsinformations sur lesles activitésactivites et programmes en cours ainsi que de stimuler les debatsdébats sur ces thematiques. Les appellations employéesemployees dans cette publication et la presentationprésentation des donnéesdonnees qui y figurent n'impliquent de la part de l'Organisation des Nations Unies pour l'alimentationI'alimentation et l'agricultureI'agriculture aucune prise de position quantQuant au statut juridique ou au stade de developpementdéveloppement des pays, territoires, villes ou zones ou dede leursleurs autorités,autorites, ni quantQuant au tracétrace de leurs frontièresfrontieres ou limites. Pour recevoir des copies de ce document, veuillez contacter: Paul Vantomme Non-wood News Forestry Officer (NWFP) Forest Products -

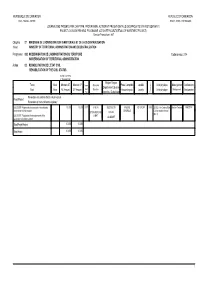

DETAILS DES PROJETS D'investissement) PROJECT LOG-BOOK PER HEAD, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJECT(DETAILS of INVESTMENT PROJECT) Exercice/ Financial Year : 2017

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX - TRAVAIL - PATRIE PEACE - WORK - FATHERLAND JOURNAL DES PROJETS PAR CHAPITRE, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJET (DETAILS DES PROJETS D'INVESTISSEMENT) PROJECT LOG-BOOK PER HEAD, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJECT(DETAILS OF INVESTMENT PROJECT) Exercice/ Financial year : 2017 Chapitre 07 MINISTERE DE L'ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION Head MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION AND DECENTRALIZATION Programme 092 MODERNISATION DE L'ADMINISTRATION DU TERRITOIRE Code service: 2004 MODERNISATION OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION Action 02 REHABILITATION DE L’ETAT CIVIL REHABILITATION OF THE CIVIL STATUS En Milliers de FCFA In Thousand CFAF Région/ Region Tache Num Montant AE Montant CP Année Structure Poste Comptable Localité Unité physique Mode gestion Gestionnaire Département/ Division Task Num AE Amount CP Amount Start Structure Accounting sta. Locality Unité physique Management Gestionnaire Year Arrondiss./ Sub-division Paragraphe Rénovation des centres d'état civil principaux Projet/Project Renovation of main civil status registery LOLODORF: Règlement des travaux de rénovation du 10 200 10 200 2017 34 00 20 SUD/ SOUTH PAIERIE LOLODORF 2230 223022 - Un Centre d'Etat Gestion Centrale MINISTRE centre d'état civil secondaire GENERALE Civil secondaire rénové DTION RESS FIN OCEAN [Qté:1] LOLODORF: Regulation of renovation work of the & MAT LOLODORF secondary civil status registery Total Projet/Project 10 200 10 200 Total Action 10 200 10 200 1 REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON -

Improving Forest Conservation and Community Livelihoods Through Income Generation from Commercial Insects in Three Kenyan Forests

CommerCial inseCts and Forest Conservation Improving Forest Conservation and Community Livelihoods through Income Generation from Commercial Insects in Three Kenyan Forests CommerCial inseCts and Forest Conservation Improving Forest Conservation and Community Livelihoods through Income Generation from Commercial Insects in Three Kenyan Forests Compiled by: Suresh K. Raina, Esther N. Kioko, Ian Gordon and Charles Nyandiga Lead Scientists: Elliud Muli, Everlyn Nguku and Esther Wang’ombe Sponsored by: UNDP/GEF and co-financed by IFAD, Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, USAID, British High Commission and Toyota Environmental Grant Facility 2009 Acknowledgements The principal authors of this report are Suresh Raina and Esther Kioko. It also draws on technical materials especially provided by Vijay Adolkar, Ken Okwae Fening, Norber Mbahin, Boniface Ngoka, Joseph Macharia, Nelly Ndung’u, Alex Munguti and Fred Barasa. The final text benefitted from Charles Nyandiga and Ian Gordon’s editorial advice and contribution. Exceptional scientific, livelihood and market research assistance on qualitative and quantitative issues has been provided by Elliud Muli, Everlyn Nguku and Esther Wang’ombe. Peer review for the study was done by Oliver Chapayama. The final editing was completed by Dolorosa Osogo and Susie Wren and typesetting and cover design by Irene Ogendo and Sospeter Makau. Thanks also for the helpful comments received from members of the stakeholders committees and advisory groups, i.e. Christopher Gakahu, Jennifer Ngige, Rose Onyango and Bernard Masiga. Thanks for the field and laboratory assistance provided by Andrew Kitheka, Anthony Maina, Beatrice Njunguna, Daniel Muia, Florence Kiilu, Gladys Mose, Jael Lumumba, James Ng’ang’a, Loise Kawira, Mary Kahinya, Newton Ngui, Regina Macharia, Stephen Amboka, Caroline Mbugua, Emily Kadambi, Joseph Kilonzo and Martin Onyango. -

Cultural Significance of Lepidoptera in Sub-Saharan Africa Arnold Van Huis

van Huis Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2019) 15:26 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-019-0306-3 RESEARCH Open Access Cultural significance of Lepidoptera in sub-Saharan Africa Arnold van Huis Abstract Background: The taxon Lepidoptera is one of the most widespread and recognisable insect orders with 160,000 species worldwide and with more than 20,000 species in Africa. Lepidoptera have a complete metamorphosis and the adults (butterflies and moths) are quite different from the larvae (caterpillars). The purpose of the study was to make an overview of how butterflies/moths and caterpillars are utilised, perceived and experienced in daily life across sub-Saharan Africa. Method: Ethno-entomological information on Lepidoptera in sub-Saharan Africa was collected by (1) interviews with more than 300 people from about 120 ethnic groups in 27 countries in the region; and (2) library studies in Africa, London, Paris and Leiden. Results: Often the interviewees indicated that people from his or her family or ethnic group did not know that caterpillars turn into butterflies and moths (metamorphosis). When known, metamorphosis may be used as a symbol for transformation, such as in female puberty or in literature regarding societal change. Vernacular names of the butterfly/moth in the Muslim world relate to religion or religious leaders. The names of the caterpillars often refer to the host plant or to their characteristics or appearance. Close to 100 caterpillar species are consumed as food. Wild silkworm species, such as Borocera spp. in Madagascar and Anaphe species in the rest of Africa, provide expensive textiles. Bagworms (Psychidae) are sometimes used as medicine.