Resolving Land-Related Conflicts Through Dialogue: Lessons from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plan D'amenagement De La Foret Communale De Mvangan

REGION DU SUD REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN SOUTH REGION REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Paix – Travail – Patrie Peace – Work ‐ Fatherland DEPARTEMENT DE LA MVILA MVILA DIVISION ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ COMMUNE DE MVANGAN MVANGAN COUNCIL B.P 1 Tél 242 69 44 06 PLAN D’AMENAGEMENT DE LA FORET COMMUNALE DE MVANGAN EFFECTUE PAR : BUREAU D’ETUDES DE PROSPECTIVES ET DE DIAGNOSTICS (BUREDIP) Agrément N°0023/MINFOF du 04 Avril 2013 1 Avantpropos La loi no 94/01 du 20 janvier 1994 portant régime des forêts, de la pêche et de la faune, marque un souci d’implication des acteurs locaux dans la gestion des ressources forestières. Elle permet aux communautés et aux communes d’acquérir et gérer des parties du domaine forestier national La création d’une forêt communale entraîne des avantages considérables pour la commune bénéficiaire. D’abord, des revenus directs seraient générés à son profit à travers la vente du bois et d’autres produits forestiers non ligneux et, éventuellement la promotion de l’écotourisme. Ensuite, des emplois pourraient être crées dans la commune (pisteurs, agents de la cellule technique de foresterie, etc.). Enfin, le bien-être des populations serait atteint car la forêt communale est une surface gérée de commun accord avec les populations locales, citoyens communaux, et bénéficiaires de la foresterie communale. La commune de MVANGAN, pour faire face à ses difficultés économiques et répondre aux sollicitations des populations en matière de développement, s’est saisie des opportunités qu’offre la politique forestière de 1993, de la loi forestière de 1994 qui en découle et des décrets d’application subséquents, notamment en ce qui concerne la gestion participative à travers l’octroi des forêts communale, leur gestion au profit de la commune, opportunités renfoncées par la loi d’orientation sur la décentralisation. -

Étude D'impact Environnemental Et Social

FONDS AFRICAIN DE DÉVELOPPEMENT DÉPARTEMENT DE L’INFRASTRUCTURE RÉPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN CAMEROUN : ROUTE SANGMÉLIMA-FRONTIERE DU CONGO ÉTUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL Aff : 09-01 Avril 2009 Etude d'impact environnemental et social de la route Sangmelima‐frontière du Congo Page i TABLE DES MATIERES I ‐ INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 I.1 ‐Contexte et justification de ce projet d’aménagement routier ....................................................... 1 I.1.1 ‐ Une vue d’ensemble du projet ................................................................................................................. 1 I.1.2 ‐ La justification du projet .......................................................................................................................... 3 I.2 ‐Objectifs de la présente étude ......................................................................................................... 4 I.3 ‐Méthodologie suivie pour la réalisation de l’étude ......................................................................... 5 I.3.1 – La collecte des données sur les enjeux du milieu récepteur .................................................................... 5 I.3.2 – L’analyse des impacts et la proposition d’un PGEIS du projet ................................................................ 6 I.4 ‐Structure du rapport ....................................................................................................................... -

A Companion Journal to Forest Ecology and Management and L

84 Volume 84 November 2017 ISSN 1389-9341 Volume 84 , November 2017 Forest Policy and Economics Policy Forest Vol. CONTENTS Abstracted / indexed in: Biological Abstracts, Biological & Agricultural Index, Current Advances in Ecological Science, Current Awareness in Biological Sciences, Current Contents AB & ES, Ecological Abstracts, EMBiology, Environment Abstracts, Environmental Bibliography, Forestry Abstracts, Geo Abstracts, GEOBASE, Referativnyi Zhurnal. Also covered in the abstract and citation database Scopus®. Full text available on ScienceDirect®. Special Issue: Forest, Food, and Livelihoods Guest Editors: Laura V. Rasmussen, Cristy Watkins and Arun Agrawal Forest contributions to livelihoods in changing Forest ecosystem services derived by smallholder agriculture-forest landscapes farmers in northwestern Madagascar: Storm hazard L.V. Rasmussen , C. Watkins and A. Agrawal (USA) 1 mitigation and participation in forest management An editorial from the handling editor R. Dave , E.L. Tompkins and K. Schreckenberg (UK) 72 S.J. Chang (United States) 9 A methodological approach for assessing cross-site 84 ( Opportunities for making the invisible visible: Towards landscape change: Understanding socio-ecological 2017 an improved understanding of the economic systems ) contributions of NTFPs T. Sunderland (Indonesia, Australia), R. Abdoulaye 1–120 C.B. Wahlén (Uganda) 11 (Indonesia), R. Ahammad (Australia), S. Asaha Measuring forest and wild product contributions to (Cameroon), F. Baudron (Ethiopia), E. Deakin household welfare: Testing a scalable household (New Zealand), J.-Y. Duriaux (Ethiopia), I. Eddy survey instrument in Indonesia (Canada), S. Foli (Indonesia, The Netherlands), R.K. Bakkegaard (Denmark), N.J. Hogarth (Finland), D. Gumbo (Indonesia), K. Khatun (Spain), I.W. Bong (Indonesia), A.S. Bosselmann (Denmark) M. Kondwani (Indonesia), M. Kshatriya (Kenya), and S. -

Brazzaville International Corridor Development Project (Mintom-Lele)

Republic of Cameroon: Yaounde – Brazzaville International Corridor Development Project (Mintom-Lele) Republic of Congo: Yaounde – Brazzaville International Corridor Development Project (Sembe-Souanke) Resettlement Due Diligence Report October 2015 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) Table of Contents Page 1. Background 1 1.1 Background and progress of the project 1 1.2 Overview of the project 2 1.3 Purpose of the study 4 2. Result of the Study 4 2.1 Degree of the land acquisition and resettlement 4 2.1.1 Population census 4 2.1.1.1 Cameroon 4 2.1.1.2 Congo 5 2.1.2 Land and asset valuation 6 2.1.2.1 Cameroon 6 2.1.2.2 Congo 7 2.2 The laws and regulations applied to the land acquisition and 8 resettlement 2.2.1 Cameroon 8 2.2.2 Congo 9 2.3 Eligibility of entitled persons for compensation against the loss of 10 property and livelihood 2.4 Responsible organization for the resettlement and their 11 responsibilities 2.4.1 Cameroon 11 2.4.2 Congo 14 2.5 Grievance and redress mechanism and status of implementation 15 2.5.1 Cameroon 15 2.5.2 Congo 16 2.6 Plans and record on compensation against the loss of property and 17 livelihood 2.6.1 Cameroon 17 2.6.1.1 Plans 17 2.6.1.2 Payment records 18 2.6.2 Congo 19 2.6.2.1 Plans 19 2.6.2.2 Payment records 20 2.7 Compensation Cost 21 2.7.1 Cameroon 21 2.7.2 Congo 21 2.8 Considerations to indigenous people 22 2.8.1 Indigenous people in the project impacted area 22 2.8.2 Socio economic characteristics of the indigenous people 23 2.8.3 Impacts associated with this project to Pygmy and measure of -

Protecting and Encouraging Customary Use of Biological

Forest Peoples Programme Protecting and encouraging customary use of biological resources by the Baka in the west of the Dja Biosphere Reserve Contribution to the implementation of Article 10(c) of the Convention on Biological Diversity Belmond Tchoumba and John Nelson with the collaboration of Georges Thierry Handja, Stephen Nounah, Emmanuel Minsolo and Bitoto Gilbert Mokomo Dieudonné Abacha Samuel Djala Luc Movombo Benjamin Alengue Ndengue Djampene Pierre Ndo Joseph Assing Didier Etong Mustapha Ndolo Samuel Claver Evina Reymondi Nsimba Josue Ati Majinot Mama Jean-Bosco Onanas Thomas Atyi Jean-Marie Megata François Sala Mefe Sylvestre Biango Felix Megolo Ze Thierry Protecting and encouraging customary use of biological resources by the Baka in the west of the Dja Biosphere Reserve Contribution to the implementation of Article 10(c) of the Convention on Biological Diversity Belmond Tchoumba and John Nelson with the collaboration of: Georges Thierry Handja, Stephen Nounah, Emmanuel Minsolo and Abacha Samuel Mama Jean-Bosco Alengue Ndengue Megata François Assing Didier Claver Megolo Bonaventure Ati Majinot Mokomo Dieudonné Atyi Jean-Marie Movombo Benjamin Biango Felix Ndo Joseph Bissiang Martin Ndolo Samuel Bitoto Gilbert Nsimba Josue Djala Luc Onanas Thomas Djampene Pierre Sala Mefe Sylvestre Etong Mustapha Ze Thierry Evina Reymondi This project was carried out with the generous support of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGIS) and the Novib-Hivos Biodiversity Fund © Forest Peoples Programme & Centre pour l’Environnement et le Développement -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

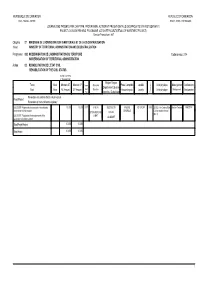

DETAILS DES PROJETS D'investissement) PROJECT LOG-BOOK PER HEAD, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJECT(DETAILS of INVESTMENT PROJECT) Exercice/ Financial Year : 2017

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX - TRAVAIL - PATRIE PEACE - WORK - FATHERLAND JOURNAL DES PROJETS PAR CHAPITRE, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJET (DETAILS DES PROJETS D'INVESTISSEMENT) PROJECT LOG-BOOK PER HEAD, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJECT(DETAILS OF INVESTMENT PROJECT) Exercice/ Financial year : 2017 Chapitre 07 MINISTERE DE L'ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION Head MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION AND DECENTRALIZATION Programme 092 MODERNISATION DE L'ADMINISTRATION DU TERRITOIRE Code service: 2004 MODERNISATION OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION Action 02 REHABILITATION DE L’ETAT CIVIL REHABILITATION OF THE CIVIL STATUS En Milliers de FCFA In Thousand CFAF Région/ Region Tache Num Montant AE Montant CP Année Structure Poste Comptable Localité Unité physique Mode gestion Gestionnaire Département/ Division Task Num AE Amount CP Amount Start Structure Accounting sta. Locality Unité physique Management Gestionnaire Year Arrondiss./ Sub-division Paragraphe Rénovation des centres d'état civil principaux Projet/Project Renovation of main civil status registery LOLODORF: Règlement des travaux de rénovation du 10 200 10 200 2017 34 00 20 SUD/ SOUTH PAIERIE LOLODORF 2230 223022 - Un Centre d'Etat Gestion Centrale MINISTRE centre d'état civil secondaire GENERALE Civil secondaire rénové DTION RESS FIN OCEAN [Qté:1] LOLODORF: Regulation of renovation work of the & MAT LOLODORF secondary civil status registery Total Projet/Project 10 200 10 200 Total Action 10 200 10 200 1 REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON -

Décret N° 2007/117 Du 24 Avril 2007 Portant Création Des Communes Le

Décret N° 2007/117 du 24 avril 2007 Portant création des communes Le président de la République décrète: Art 1er : Sont créées, à compter de la date de signature du présent décret, les communes ci-après désignées: PROVINCE DE L'ADAMAOUA Département de la Vina Commune de Nganha Chef-lieu: Nganha Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Nganha. Commune de Ngaoundéré 1er Chef-lieu: Mbideng Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Ngaoundéré 1er. Commune de Ngaoundéré Ile Chef-lieu: Mabanga Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Ngaoundéré Ile. Commune de Ngaoundéré Ille Chef-lieu: Dang Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Ngaoundéré Ille Commune de Nyambaka Chef-lieu: Nyambaka Le ressort territorial de ladite commune, couvre l'arrondissement de Nyambaka Commune de Martap Chef-lieu: Martap Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Martap. PROVINCE DU CENTRE Département du Mbam et Inoubou Commune de Bafia Chef-lieu : Bafia Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Bafia. Commune de Kiiki Chef-lieu: Kiiki Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Kiiki Commune de Kon-Yambetta Chef-lieu: Kom- Yambetta Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de KomYambetta Département du Mfoundi Commune d'arrondissement de Yaoundé VII Chef-lieu : Nkolbisson Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Nkolbisson. La composition de la Communauté Urbaine de Yaoundé et le ressort territorial de la commune d'arrondissement de Yaoundé Ile sont modifiés en conséquence 1 PROVINCE DE L'EST Département du Lom et Djerem Commune de Bertoua 1 er Chef-lieu : Nkolbikon Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Bertoua 1er. -

Plan Communal De Développement De Meyomessala Commune De

Plan Communal de développement de Meyomessala SOMMAIRE RESUME ............................................................................................................................... 4 LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ................................................................................................. 6 LISTE DES PHOTOS ............................................................................................................ 9 LISTE DES CARTES............................................................................................................10 LISTE DES ANNEXES .........................................................................................................12 1. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................13 1.1 Contexte et justification ...............................................................................................14 1.2 Objectifs du PCD ........................................................................................................15 1.3 Structure du PCD .......................................................................................................15 2. METHODOLOGIE ........................................................................................................16 2.1 Préparation de l’ensemble du processus...............................................................17 2.2 Collecte des informations et traitement .......................................................................18 2.3 -

Irvingia Spp. from Southern Cameroon

FORPOL-01522; No of Pages 9 Forest Policy and Economics xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Policy and Economics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/forpol Challenges to governing sustainable forest food: Irvingia spp. from southern Cameroon Verina Ingram a,b,⁎,MarcusEwanec, Louis Njie Ndumbe d, Abdon Awono a a Center for International Forestry Research, BP 2008, Messa, Yaoundé, Cameroon b Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Group, Wageningen UR, P.O. Box 47, 6708 PB Wageningen, The Netherlands c Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine School of Pharmacy, 1858 West Grandview Boulevard, Erie, PA 16509 – 1025, USA d University of Dschang, Faculty of Agronomy and Agricultural Sciences, BP 222, Dschang, Cameroon article info abstract Article history: Across the Congo Basin, bush mango (Irvingia spp.) nuts have been harvested from forest landscapes for consump- Received 16 May 2016 tion, sold as a foodstuff and for medicine for centuries. Data on this trade however are sparse. A value chain approach Received in revised form 21 December 2016 was used to gather information on stakeholders in the chain from the harvesters in three major production areas in Accepted 22 December 2016 Cameroon to traders in Cameroon, Nigeria, and Equatorial Guinea, the socio-economic values, environmental Available online xxxx sustainability and governance. Around 5190 people work in the complex chain in Cameroon with an estimated 4109 tons harvested on average annually in the period 2007 to 2010. Bush mango incomes contribute on average Keywords: Irvingia spp. to 31% of harvester's annual incomes and dependence increases for those further from the forest. -

Palm Oil Development in Cameroon

THIS PUBLICATION HAS BEEN PUBLISHED IN PARTNERSHIP WITH: REPORT APRIL 2012 Oil Palm Development in Cameroon An ad hoc working paper prepared by David Hoyle (WWF Cameroon) and Patrice Levang (IRD/CIFOR) C r e d i t : P . L e v a n g Smallholder palm oil production provides many job opportunities (Mbongo, Littoral, Cameroon) Biography David Hoyle is the Conservation Director for WWF Cameroon. A trained socio- economist; he has been working in natural resource management in Cameroon for WWF and also WCS for over 7 years. www.panda.org Patrice Levang is a researcher at IRD (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, France), presently seconded to CIFOR (Centre for International Forestry Research) in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Agro-economist by training, his research has mainly been focusing on the agricultural colonization –organized and spontaneous- of the forest margins of the Indonesian archipelago. Since October 2010 he relocated to Cameroon where he studies the livelihoods impacts of forest conversion. www.ird.fr www.cifor.org CONTEXT Palm oil ( Elæis Palm oil, with an annual global production of 50 million tons, equating to 39% of world production of vegetable oils, has become the most important guineensis ) is a plant vegetable oil globally, greatly exceeding soybean, rapeseed and sunflower native to the (USDA, 2011). More than 14 million hectares of oil palm have been planted countries bordering across the tropics. Palm oil is a highly profitable product for the producers; the Gulf of Guinea. the industry is worth at least USD 20 billion annually. Palm oil is a common Extracted from the cooking ingredient in the tropical belt of Africa, Southeast Asia and parts of Brazil. -

Programmation De La Passation Et De L'exécution Des Marchés Publics

PROGRAMMATION DE LA PASSATION ET DE L’EXÉCUTION DES MARCHÉS PUBLICS EXERCICE 2021 JOURNAUX DE PROGRAMMATION DES MARCHÉS DES SERVICES DÉCONCENTRÉS ET DES COLLECTIVITÉS TERRITORIALES DÉCENTRALISÉES RÉGION DU SUD EXERCICE 2021 SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de Montant des N° Désignation des MO/MOD N° page Marchés Marchés 1 Services Réconcentrés Régionaux 15 764 034 000 3 2 Communauté Urbaine d'Ebolowa 3 445 822 672 5 3 Communauté Urbaine de Kribi 1 20 000 000 6 Département du Dja et Lobo 4 Services Déconcentrés Départementaux 8 426 000 000 7 5 Commune de Sangmelima 9 278 550 000 8 6 Commune de Bengbis 13 280 500 000 9 7 Commune d'Oveng 15 353 500 000 10 8 Commune de Meyomessala 27 529 260 000 12 9 Commune de Meyomessi 29 393 260 000 14 10 Commune de Djoum 9 226 100 000 17 11 Commune de Zoétélé 12 722 126 446 18 12 Commune de Mintom 9 234 150 000 19 TOTAL Département 131 3 443 446 446 Département de la Mvila 13 Services Déconcentrés Départementaux 4 230 662 992 21 14 Commune d'Ebolowa I 12 182 973 567 21 15 Commune d'Ebolowa II 14 246 429 999 22 16 Commune de Bowong-Bané 11 215 500 000 23 17 Commune de Biwong-Bulu 16 275 350 000 24 18 Commune de Mengong 8 188 000 000 25 19 Commune de Ngoulemakong 14 228 499 568 26 20 Commune de Mvangan 11 255 100 000 27 21 Commune d'Efoulan 6 152 250 000 28 TOTAL Département 96 1 974 766 126 MINMAP/Division de la Programmation et du Suivi des Marchés Publics Page 1 sur 42 SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de Montant des N° Désignation des