Irvingia Spp. from Southern Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Back Grou Di Formatio O the Co Servatio Status of Bubi Ga Ad We Ge Tree

BACK GROUD IFORMATIO O THE COSERVATIO STATUS OF BUBIGA AD WEGE TREE SPECIES I AFRICA COUTRIES Report prepared for the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO). by Dr Jean Lagarde BETTI, ITTO - CITES Project Africa Regional Coordinator, University of Douala, Cameroon Tel: 00 237 77 30 32 72 [email protected] June 2012 1 TABLE OF COTET TABLE OF CONTENT......................................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................................... 4 ABREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................. 5 ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................... 6 0. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................10 I. MATERIAL AND METHOD...........................................................................................11 1.1. Study area..................................................................................................................11 1.2. Method ......................................................................................................................12 II. BIOLOGICAL DATA .....................................................................................................14 2.1. Distribution of Bubinga and Wengé species in Africa.................................................14 -

Étude D'impact Environnemental Et Social

FONDS AFRICAIN DE DÉVELOPPEMENT DÉPARTEMENT DE L’INFRASTRUCTURE RÉPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN CAMEROUN : ROUTE SANGMÉLIMA-FRONTIERE DU CONGO ÉTUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL Aff : 09-01 Avril 2009 Etude d'impact environnemental et social de la route Sangmelima‐frontière du Congo Page i TABLE DES MATIERES I ‐ INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 I.1 ‐Contexte et justification de ce projet d’aménagement routier ....................................................... 1 I.1.1 ‐ Une vue d’ensemble du projet ................................................................................................................. 1 I.1.2 ‐ La justification du projet .......................................................................................................................... 3 I.2 ‐Objectifs de la présente étude ......................................................................................................... 4 I.3 ‐Méthodologie suivie pour la réalisation de l’étude ......................................................................... 5 I.3.1 – La collecte des données sur les enjeux du milieu récepteur .................................................................... 5 I.3.2 – L’analyse des impacts et la proposition d’un PGEIS du projet ................................................................ 6 I.4 ‐Structure du rapport ....................................................................................................................... -

De 45 Adjoints D'administration

AO/CBGI REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix –Travail – Patrie Peace – Work – Fatherland -------------- --------------- MINISTERE DE LA FONCTION PUBLIQUE MINISTRY OF THE PUBLIC SERVICE ET DE LA REFORME ADMINISTRATIVE AND ADMINISTRATIVE REFORM --------------- --------------- SECRETARIAT GENERAL SECRETARIAT GENERAL --------------- --------------- DIRECTION DU DEVELOPPEMENT DEPARTMENT OF STATE HUMAN DES RESSOURCES HUMAINES DE L’ETAT RESSOURCES DEVELOPMENT --------------- --------------- SOUS-DIRECTION DES CONCOURS SUB DEPARTMENT OF EXAMINATIONS ------------------ -------------------- CONCOURS DIRECT POUR LE RECRUTEMENT DE 45 ADJOINTS D’ADMINISTRATION SESSION 2020 CENTRE D’EBOLOWA LISTE DES CANDIDATS AUTORISÉS À SUBIR LES ÉPREUVES ÉCRITES DU 12 SEPTEMBRE 2020 RÉGION DÉPARTEMENT NO MATRICULE NOMS ET PRÉNOMS DATE ET LIEU DE NAISSANCE SEXE LANGUE D’ORIGINE D’ORIGINE 1. AAL4428 ABESSOLO BELINGA MARQUISE 07/07/1998 A EBOLOWA F SU MVILA F 2. AAL1019 ABOMO MINKOULOU MONIQUE AURELIE 28/12/1992 A BENGBIS F SU DJA ET LOBO F 3. AAL5292 ABOSSSOLO MARTHE BRINDA 15/12/2000 A EBOLOWA F SU MVILA F 4. AAL3243 ABOUTOU MEBA CAROLE DEBORA 03/06/1996 A SANGMELIMA F SU DJA ET LOBO F 5. AAL2622 ADA MBEA CHRISTELLE FALONNE 10/06/1995 A MENDJIMI F SU VALLEE DU NTEM F 6. AAL1487 ADJOMO OBAME JOSSELINE 28/08/1993 A YAOUNDE F SU DJA ET LOBO F 7. AAL3807 AFA'A POMBA VALERE GHISLAIN 28/04/1997 A AWAE M SU DJA ET LOBO F 8. AAL4597 AFANE BERTHOLD 15/11/1998 A KONGO-NDONG M SU DJA ET LOBO F MINFOPRA/SG/DDRHE/SDC|Liste générale des candidats Adjoints d’Administration, session 2020_Ebolowa Page 1 9. AAL4787 AFANE MALORY 27/05/1999 A MBILEMVOM F SU DJA ET LOBO F 10. -

A Companion Journal to Forest Ecology and Management and L

84 Volume 84 November 2017 ISSN 1389-9341 Volume 84 , November 2017 Forest Policy and Economics Policy Forest Vol. CONTENTS Abstracted / indexed in: Biological Abstracts, Biological & Agricultural Index, Current Advances in Ecological Science, Current Awareness in Biological Sciences, Current Contents AB & ES, Ecological Abstracts, EMBiology, Environment Abstracts, Environmental Bibliography, Forestry Abstracts, Geo Abstracts, GEOBASE, Referativnyi Zhurnal. Also covered in the abstract and citation database Scopus®. Full text available on ScienceDirect®. Special Issue: Forest, Food, and Livelihoods Guest Editors: Laura V. Rasmussen, Cristy Watkins and Arun Agrawal Forest contributions to livelihoods in changing Forest ecosystem services derived by smallholder agriculture-forest landscapes farmers in northwestern Madagascar: Storm hazard L.V. Rasmussen , C. Watkins and A. Agrawal (USA) 1 mitigation and participation in forest management An editorial from the handling editor R. Dave , E.L. Tompkins and K. Schreckenberg (UK) 72 S.J. Chang (United States) 9 A methodological approach for assessing cross-site 84 ( Opportunities for making the invisible visible: Towards landscape change: Understanding socio-ecological 2017 an improved understanding of the economic systems ) contributions of NTFPs T. Sunderland (Indonesia, Australia), R. Abdoulaye 1–120 C.B. Wahlén (Uganda) 11 (Indonesia), R. Ahammad (Australia), S. Asaha Measuring forest and wild product contributions to (Cameroon), F. Baudron (Ethiopia), E. Deakin household welfare: Testing a scalable household (New Zealand), J.-Y. Duriaux (Ethiopia), I. Eddy survey instrument in Indonesia (Canada), S. Foli (Indonesia, The Netherlands), R.K. Bakkegaard (Denmark), N.J. Hogarth (Finland), D. Gumbo (Indonesia), K. Khatun (Spain), I.W. Bong (Indonesia), A.S. Bosselmann (Denmark) M. Kondwani (Indonesia), M. Kshatriya (Kenya), and S. -

Resolving Land-Related Conflicts Through Dialogue: Lessons from The

Resolving land-related conflicts through dialogue: Lessons from the outskirts of a protected area in Cameroon Michelle Sonkoue, Romuald Ngono and Anna Bolin Legal tools for citizen empowerment Around the world, citizens’ groups are taking action to change the way investment in natural resources is happening and to protect rights and the environment for a fairer and more sustainable world. IIED’s Legal Tools for Citizen Empowerment initiative develops analysis, tests approaches, documents lessons and shares tools and tactics amongst practitioners (www.iied.org/legal-tools). The Legal Tools for Citizen Empowerment series provides an avenue for practitioners to share lessons from their innovative approaches to claim rights. This ranges from grassroots action and engaging in legal reform, to mobilising international human rights bodies and making use of grievance mechanisms, through to scrutinising international investment treaties, contracts and arbitration. This paper is one of a number of reports by practitioners on their lessons from such approaches. Other reports can be downloaded from www.iied.org/pubs and include: • Rebalancing power in global food chains through a “Ways of Working” approach: an experience from Kenya. 2019. Kariuki, E and Kambo, M • A stronger voice for women in local land governance: effective approaches in Tanzania, Ghana and Senegal. 2019. Sutz, P et al. • Improving accountability in agricultural investments: Reflections from legal empowerment initiatives in West Africa. 2017. Cotula, L and Berger, T (eds.) • Advancing indigenous peoples’ rights through regional human rights systems: The case of Paraguay. 2017. Mendieta Miranda, M. and Cabello Alonso, J • Connected and changing: An open data web platform to track land conflict in Myanmar. -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Ntem

'1 ---~-- OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE REPUBLIQUE FEDERALE SCIENTIFIQUE ET T~CHNIQUE DU OUTRE-MER CAMEROUN CENTRE ORSTOM DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU NTEM 2eme E DillON 1 D'ap,es la documentat;on ,éun;e p-:; la Section de Géographie de l'ORSTOM REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN FASCICULE N° 6 YAOUNDE SH. n° 46 Juin 1968 REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN Fasc. Tableau de la population du Cameroun, 68 p. Fév. 1965 SH. Ne 17 Fasc. 2 Dictionnaire des villages du Dia et Lobo, 89 p. Juin 1965 SH. N° 22 Fasc. 3 Dictionnaire des villages de la Haute-Sanaga, 53 p. Août 1965 SH. N° 23 Fasc. 4 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Mfoumou, 49 p. Octobre 1965 SH. Ne ?4 Fasc. 5 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Soo 45 p. Novembre 1965 SH. N° 25 er Fasc. 6 Dictionnaire des villages du Ntem 102 p. Juin 1968 SH. N° 46 (2 ,e édition) Fasc. 7 Dictionnaire des villages de la Mefou 108 p. Janvier 1966 SH. N° 27 Fasc. 8 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Kellé 51 p. Février 1966 SH. N° 28 Fasc. 9 Dictionnaire des villages de la Lékié 71 p. Mars 1966 SH. Ne ';9 Fasc. 10 Dictionnaire des villages de Kribi P. Mars 1966 SH. N° 30 Fasc. 11 Dictionnaire des villages du Mbam 60 P. Mai 1966 SH. N° 31 Fasc. 12 Dictionnaire des villages de Boumba Ngoko 34 p. Juin 1966 SH. 39 Fasc. 13 Dictionnaire des villages de Lom-et-Diérem 35 p. Juillet 1967 SH. 40 Fasc. -

Protecting and Encouraging Customary Use of Biological

Forest Peoples Programme Protecting and encouraging customary use of biological resources by the Baka in the west of the Dja Biosphere Reserve Contribution to the implementation of Article 10(c) of the Convention on Biological Diversity Belmond Tchoumba and John Nelson with the collaboration of Georges Thierry Handja, Stephen Nounah, Emmanuel Minsolo and Bitoto Gilbert Mokomo Dieudonné Abacha Samuel Djala Luc Movombo Benjamin Alengue Ndengue Djampene Pierre Ndo Joseph Assing Didier Etong Mustapha Ndolo Samuel Claver Evina Reymondi Nsimba Josue Ati Majinot Mama Jean-Bosco Onanas Thomas Atyi Jean-Marie Megata François Sala Mefe Sylvestre Biango Felix Megolo Ze Thierry Protecting and encouraging customary use of biological resources by the Baka in the west of the Dja Biosphere Reserve Contribution to the implementation of Article 10(c) of the Convention on Biological Diversity Belmond Tchoumba and John Nelson with the collaboration of: Georges Thierry Handja, Stephen Nounah, Emmanuel Minsolo and Abacha Samuel Mama Jean-Bosco Alengue Ndengue Megata François Assing Didier Claver Megolo Bonaventure Ati Majinot Mokomo Dieudonné Atyi Jean-Marie Movombo Benjamin Biango Felix Ndo Joseph Bissiang Martin Ndolo Samuel Bitoto Gilbert Nsimba Josue Djala Luc Onanas Thomas Djampene Pierre Sala Mefe Sylvestre Etong Mustapha Ze Thierry Evina Reymondi This project was carried out with the generous support of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGIS) and the Novib-Hivos Biodiversity Fund © Forest Peoples Programme & Centre pour l’Environnement et le Développement -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

INTERACTIVE FOREST ATLAS of CAMEROON Version 3.0 | Overview Report

INTERACTIVE FOREST ATLAS OF CAMEROON Version 3.0 | Overview Report WRI.ORG Interactive Forest Atlas of Cameroon - Version 3.0 a Design and layout by: Nick Price [email protected] Edited by: Alex Martin TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Foreword 4 About This Publication 5 Abbreviations and Acronyms 7 Major Findings 9 What’s New In Atlas Version 3.0? 11 The National Forest Estate in 2011 12 Land Use Allocation Evolution 20 Production Forests 22 Other Production Forests 32 Protected Areas 32 Land Use Allocation versus Land Cover 33 Road Network 35 Land Use Outside of the National Forest Estate 36 Mining Concessions 37 Industrial Agriculture Plantations 41 Perspectives 42 Emerging Themes 44 Appendixes 59 Endnotes 60 References 2 WRI.org F OREWORD The forests of Cameroon are a resource of local, Ten years after WRI, the Ministry of Forestry and regional, and global significance. Their productive Wildlife (MINFOF), and a network of civil society ecosystems provide services and sustenance either organizations began work on the Interactive Forest directly or indirectly to millions of people. Interac- Atlas of Cameroon, there has been measureable tions between these forests and the atmosphere change on the ground. One of the more prominent help stabilize climate patterns both within the developments is that previously inaccessible forest Congo Basin and worldwide. Extraction of both information can now be readily accessed. This has timber and non-timber forest products contributes facilitated greater coordination and accountability significantly to the national and local economy. among forest sector actors. In terms of land use Managed sustainably, Cameroon’s forests consti- allocation, there have been significant increases tute a renewable reservoir of wealth and resilience. -

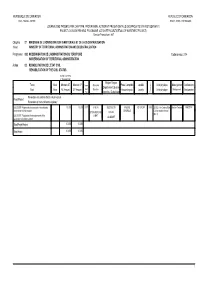

DETAILS DES PROJETS D'investissement) PROJECT LOG-BOOK PER HEAD, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJECT(DETAILS of INVESTMENT PROJECT) Exercice/ Financial Year : 2017

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX - TRAVAIL - PATRIE PEACE - WORK - FATHERLAND JOURNAL DES PROJETS PAR CHAPITRE, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJET (DETAILS DES PROJETS D'INVESTISSEMENT) PROJECT LOG-BOOK PER HEAD, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJECT(DETAILS OF INVESTMENT PROJECT) Exercice/ Financial year : 2017 Chapitre 07 MINISTERE DE L'ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION Head MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION AND DECENTRALIZATION Programme 092 MODERNISATION DE L'ADMINISTRATION DU TERRITOIRE Code service: 2004 MODERNISATION OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION Action 02 REHABILITATION DE L’ETAT CIVIL REHABILITATION OF THE CIVIL STATUS En Milliers de FCFA In Thousand CFAF Région/ Region Tache Num Montant AE Montant CP Année Structure Poste Comptable Localité Unité physique Mode gestion Gestionnaire Département/ Division Task Num AE Amount CP Amount Start Structure Accounting sta. Locality Unité physique Management Gestionnaire Year Arrondiss./ Sub-division Paragraphe Rénovation des centres d'état civil principaux Projet/Project Renovation of main civil status registery LOLODORF: Règlement des travaux de rénovation du 10 200 10 200 2017 34 00 20 SUD/ SOUTH PAIERIE LOLODORF 2230 223022 - Un Centre d'Etat Gestion Centrale MINISTRE centre d'état civil secondaire GENERALE Civil secondaire rénové DTION RESS FIN OCEAN [Qté:1] LOLODORF: Regulation of renovation work of the & MAT LOLODORF secondary civil status registery Total Projet/Project 10 200 10 200 Total Action 10 200 10 200 1 REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON -

Est Centre Sud Littoral Ouest Est

Bazou IBRD 32132 5˚ 5˚ NDE NOUN 11˚ 12˚ 13˚ CAMEROON Tonga Nkongsamba OUEST PETROLEUMHAUT- DEVELOPMENT Bélabo AND PIPELINE PROJECT NKAM Nkongjok LOM-ET- Nginda Sanaga Towns and Villages Mentioned in Request Bafia DJEREM Ndikiniméki Mougué Rivers Mentioned in Request Pipeline Route Nanga Eboko Bakola Territory Nginda Ombessa MBAM Bakola Camps (1983 study, LOUNG, 1996) Ngamba Minta Bokito Rivers Wouri Yingui HAUTE-SANAGA YabassiMajor Rivers Nkoteng Paved Roads Ntuj All-Weather Roads Mbandjok Dim NKAM Ndom Nguélémendouka Unsurfaced Roads Saa Tracks/Trails Doume Railroads LITTORAL Monatélé Selected Towns/Villages Ngambé Department Capitals Obala Province Capital Nkon Ngok CENTRE National Capital LEKIE Essé Evodoula Abong Department Boundaries Sanaga Okola Mbang 4˚ 4˚ Province Boundaries Bot Makak Ngog Mapubi MEFOU Awaé NYONG-ET MFOUMOU Ayos 10˚ EST Pouma YAOUNDÉ Edéa Matomb Mbankomo Akonolinga Dzeng HAUT-NYONG SANAGA-MARITIME NYONG-ET-KELLE Mfou Messaména Messondo MFOUNDI Eséka Bikok Ngoumou Makak Nkongzok 1 Akono Mbalmayo Nyong Endom 10° 12° Lake 16° Elogbatindi Bengbis Chad ° 12 12° Nkoala'a CHAD CHAD Mvengué CAMEROON NYONG-ET-SO 10° 10° Ngovayang 2 Ngomedzap Bakola or Saballi Zoétélé Fifinda Bagyeli Bili-bi- Tchop Lolodorf Mbikiliki 8° 8° Bidjouka NIGERIA Lokoundjé Mougué Bikoui Gulf of Kouambo DJA-ET-LOBO CAMEROON Guinea Bandevouri Bipindi Ngoulemakong CENTRAL 6° Makouré 1 AFRICAN Dja 3˚ REPUBLIC 3˚ Kour Loundabele Tchangué Kribi Mintoum Sangmélima Area of Map Nkaga Zalé Ebolowa 4° 4° This map was produced by the YAOUNDE Mpango 0204060 80 100 Map Design Unit of The World Bank. OCEAN SUD The boundaries, colors, denominations Ebomé Kienké and any other information shown on this map do not imply, on the part of ATLANTIC For Detail, see Pembo River/swamp KILOMETERS The World Bank Group, any judgment OCEAN 10˚ Akom II 11˚ 12˚ on the legal status of any territory, or 13˚ IBRD 32148 any endorsement or acceptance of 2° NTEM such boundaries. -

Plan Communal De Développement De Meyomessala Commune De

Plan Communal de développement de Meyomessala SOMMAIRE RESUME ............................................................................................................................... 4 LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ................................................................................................. 6 LISTE DES PHOTOS ............................................................................................................ 9 LISTE DES CARTES............................................................................................................10 LISTE DES ANNEXES .........................................................................................................12 1. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................13 1.1 Contexte et justification ...............................................................................................14 1.2 Objectifs du PCD ........................................................................................................15 1.3 Structure du PCD .......................................................................................................15 2. METHODOLOGIE ........................................................................................................16 2.1 Préparation de l’ensemble du processus...............................................................17 2.2 Collecte des informations et traitement .......................................................................18 2.3