The Cuban Missile Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albert Wohlstetter's Legacy: the Neo-Cons, Not Carter, Killed

SPECIAL REPORT: NUCLEAR SABOTAGE ALBERT WOHLSTETTER’S LEGACY Wohlstetter was even stranger than the “Dr. Strangelove” depicted in the 1964 movie of that name. An early draft of the film was titled “The Delicate Balance of Terror,” the same title as Wohlstetter’s best-known unclassified work. Here, a still from the film. tives—Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, and Zalmay Khalilzad, to name a few. In Wohlstetter’s circle of influence were also Ahmed Chalabi (whom Wohlstetter championed), Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D-Wash.), Sen. Robert Dole (R- Kan.), and Margaret Thatcher. Wohlstetter himself was a follower of Bertrand Russell, not only in mathematics, but in world outlook. The pseudo-peacenik Russell had called for a preemptive strike against the Soviet Union, after World War II and before the Soviets developed the bomb, as a prelude to his plan for bully- ing nations into a one-world government. Russell, a raving Malthusian, opposed economic development, especially in the Third World. Admirer Jude Wanniski wrote of Wohlstetter in an obituary, “[I]t is no exaggeration, I think, to say that Wohlstetter was the most influential unknown man in the world for the past half century, and easily in the top ten in importance of all men.” “Albert’s decisions were not automat- ically made official policy at the White House,” Wanniski wrote, “but Albert’s The Neo-Cons, Not Carter, genius and his following were such in the places where it counted in the Establishment that if his views were Killed Nuclear Energy resisted for more than a few months, it -

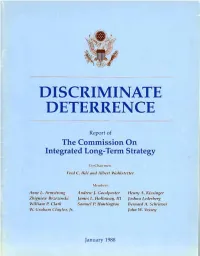

Discriminate Deterrence

DISCRIMINATE DETERRENCE Report of The Commission On Integrated Long-Term Strategy Co -C. I lairmea: Fred C. lkle and Albert Wohlstetter Moither, Anne L. Annsinmg Andrew l. Goodraster flenry /1 Kissinger Zbign ei Brzezinski fames L. Holloway, Ur Joshua Lederberg William P. Clark Samuel P. Huntington Bernard A. Schriever tV. Graham Ciaytor, John W. Vessey January 1988 COMMISSION ON INTEGRATED LONG-TERM STRATEGY January 11. 1988 MEMORANDUM FOR: THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE THE ASSISTANT TO THE PRESIDENT FOR NATIONAL SECURITY AFFAIRS We are pleased to present this final report of Our Commission. Pursuant to your initial mandate, the report proposes adjustments to US. military strategy in view of a changing security environment in the decades ahead. Over the last fifteen months the Commission has received valuable counsel from members of Congress, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Service Chiefs. and the Presdent's Science Advisor, Members of the National Security Council Staff, numerous professionals in the Department of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency, and a broad range of specialists outside the government provided unstinting support. We are also indebted to the Commission's hardworking staff. The Commission was supported generously by several specialized study groups that closely analyzed a number of issues, among them: the security environment for the next twenty years, the role of advanced technology in military systems, interactions between offensive and defensive systems on the periphery of the Soviet Union, and the U.S, posture in regional conflicts around the world. Within the next few months, these study groups will publish detailed findings of their own. -

Émigrés and Anglo-American Intelligence Operations in the Early Cold War Cacciatore, F

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch “Their Need Was Great”: Émigrés and Anglo-American Intelligence Operations in the Early Cold War Cacciatore, F. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr Francesco Cacciatore, 2018. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] “Their Need Was Great”: Émigrés and Anglo-American Intelligence Operations in the Early Cold War Francesco Alexander Cacciatore March 2018 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract Covert action during the Cold War has been the subject of much historiography. This research, however, is based for the most part on primary sources, specifically on the records declassified in the United States in 2007 as a consequence of the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act. The majority of the historiography on this topic either predates or neglects these records. The study of covert operations inside the Iron Curtain during the early Cold War, sponsored by Western states using émigré agents, usually ends with the conclusion that these operations were a failure, both in operational terms and from the point of view of the intelligence gathered. -

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Paul Harold Rubinson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War Committee: —————————————————— Mark A. Lawrence, Supervisor —————————————————— Francis J. Gavin —————————————————— Bruce J. Hunt —————————————————— David M. Oshinsky —————————————————— Michael B. Stoff Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War by Paul Harold Rubinson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Acknowledgements Thanks first and foremost to Mark Lawrence for his guidance, support, and enthusiasm throughout this project. It would be impossible to overstate how essential his insight and mentoring have been to this dissertation and my career in general. Just as important has been his camaraderie, which made the researching and writing of this dissertation infinitely more rewarding. Thanks as well to Bruce Hunt for his support. Especially helpful was his incisive feedback, which both encouraged me to think through my ideas more thoroughly, and reined me in when my writing overshot my argument. I offer my sincerest gratitude to the Smith Richardson Foundation and Yale University International Security Studies for the Predoctoral Fellowship that allowed me to do the bulk of the writing of this dissertation. Thanks also to the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy at Yale University, and John Gaddis and the incomparable Ann Carter-Drier at ISS. -

New Exhibit Explores John F. Kennedy's Early Life

ISSUE 20 H WINTER 2016 THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND PUBLIC PROGRAMS AT THE JOHN F. KENNEDY PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM New Exhibit Explores John F. Kennedy’s Early Life efore he was president, John F. Kennedy was known simply as “Jack” to his friends and family. Young Jack, a new permanent exhibit at the BJohn F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, features documents, photographs, and objects that provide an intimate look at his childhood and family life, intellectual development, foreign travels, and military service. Through engagement with these primary sources, students may explore how a somewhat Senator John F. Kennedy signs a copy of Profiles rebellious, fun-loving and academically under-achieving teenager took a serious in Courage for a young fan, ca.1956–1957. interest in international affairs and started on the path of leadership that would Profiles in Courage one day lead to the White House. Turns 60! School Years In 1954, John F. Kennedy took a A wooden desk from Choate, the private boarding school he attended from leave of absence from the Senate 1931-35, evokes the time Jack spent there as a spirited high school student to undergo back surgery. During struggling to keep his grades up. Accompanying the desk are revealing excerpts his recuperation, he set to work researching and writing the stories from correspondence between Jack and his father, along with this quote from of US senators whom he considered a report by his housemaster: to have shown great courage under “Jack studies at the last minute, keeps appointments late, has little enormous pressure from their parties and their constituents: John Quincy sense of material value, and can seldom locate his possessions.” Adams, Daniel Webster, Thomas Hart Young people who are experiencing their own challenges, Benton, Sam Houston, Edmund G. -

Index to the US Department of State Documents Collection, 2010

Description of document: Index to the US Department of State Documents Collection, 2010 Requested date: 13-May-2010 Released date: 03-December-2010 Posted date: 09-May-2011 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Officer Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL US Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Notes: This index lists documents the State Department has released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) The number in the right-most column on the released pages indicates the number of microfiche sheets available for each topic/request The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

There Are Other Ossenkos

• TAMPA, FLORIDA TRIBUNE m. 150,478 S. 164,063 Front Edif* 0 that, P.g. Pa :,,,:+91 1, 2 1964 Date: FEB 1. There Are Other Ossenkos . Whether or not Yuri Ivanovich er notable examples are Igor Gou- Ossenko. Russian secret police zenko in Canada, 1947; Nikolay! staff officer who has sought Khokhlov, West Germany, Juri! asylum in the U.S., knows secrets Rastvorov, Japan, Peter Deriabin,' of Soviet nuclear weapons produc- Vienna, and Vadimir Petrov, Aus-: tion, as some Western sources spe- tralia, all in 1954; and Bogdon Sta. culate, his defection is a hard blow shinski, West Germany, in 1961. to Red intelligence. „CIA. Director Allen Dulles, in The idea that he may have in- his recent book, "The Craft of In- formation on atomic weapons telligence," noted that the prin- arises from the fact that Ossenko cipal value of such 'defectors was; was serving as security officer for that "one such intelligence 'volun-J the Red delegation at the Geneva teer' can literally paralyze the disarmament parley at the time of service he left behind for months his defection. to come" because of what he knows. and tells of policies, plans, current. Based on the previous pattern 9perations and secret agents. of Russian delegations to confer- That Ossenko's - value: to the ences in other countries, this meant is even greater than simply that Ossenko was a highly trusted his knOwledge of Soviet nuclear. agent detailed to keep close rein capabilities should be comforting' on the actual members of the dele- to all citizens of the U.S. -

US-Soviet Summit November-December 1987

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Ermarth, Fritz W.: Files Folder Title: US-Soviet Summit November 1987 - December 1987 (5) Box: RAC Box 1 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name ERMATH, FRITZ: FILES Withdrawer MID 4/19/2013 File Folder US - SOVIET SUMMIT: NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 1987 (5) FOIA F02-073/5 Box Number RAC BOX 1 COLLINS 85 ID Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions Pages 157588 MEMO ROBERT RISCASSI TO GRANT GREEN 2 11/20/1987 Bl RE SUMMIT 157589 MEMO FRANK CARLUCCI TO THE PRESIDENT 5 11/20/1987 B 1 RE SCOPE PAPER 157590 SCOPE PAPER RE KEY ISSUES FOR THE SUMMIT 7 ND Bl 157591 MEMO FRITZ ERMARTH TO FRANK CARLUCCI 1 11/19/1987 Bl RE SCOPE PAPER 157592 MEMO WILLIAM MATZ TO GRANT GREEN RE 3 11/23/1987 B 1 SUMMIT (W/ATTACHMENTS) The above documents were not referred for declassification review at time of processing Freedom of Information Act• (5 U.S.C. 552(b)J B-1 Natlonal aecurlty claaalfled Information [(b)(1) of the FOIAJ B-2 Releaae would dlacloae Internal personnel rulea and practices of an agency [(b)(2) of the FOIAJ B-3 Releaae would -

Interview with Ted Sorensen, President Kennedy's Speechwriter by Sherry and Jenny Thompson, February 2010

Sorensen interview with Jenny and Sherry February 2010 Q. Your relationship to Thompson and his to Kennedy When John F. Kennedy was elected president in 1960, one of the reasons he ran was because at the height of the Cold War he was fearful that the Eisenhower/Dulles foreign policy of massive retaliation might only lead to nuclear war. Your father, Llewellyn Thompson, who had been US ambassador in Moscow during those late 50’s years was I’m quite certain a career a foreign service officer who was appointed I’m not sure what his title was counselor or maybe Ambassador at Large in the State Department. When CMC broke, (and more details in my new book called Councilor: Life at the Edge of History) on Oct. 16 the first of 13 memorable days of 1962. Historians still call them the 13 most dangerous days in the history of mankind. Because a misstep a wrong move could have started a war which would have turned very quickly into a nuclear exchange. And if the first step were Soviets firing tactical nuclear weapons, The United States, would have responded at least with tactical nuclear weapons and once both sides were on that nuclear escalator, they would have moved up to strategic weapons and then to all-out warfare, and the scientists say that the explosion of so many large nuclear weapons in both eastern Europe and in North America would have produced, in addition to the bombardment of 100s of thousands and millions of people in both countries, would have resulted in radioactive poisoning of the atmosphere and in time of every dimension of our planet and would be speed via wind and water and even soil to the far reaches of the planet until that planet was uninhabitable: no plant life, no animal life, no human life, and we you and I would not be talking right now. -

July-August 2017

July-August 2017 A Monthly Publication of the U.S. Consulate Krakow Volume VIII. Issue 5. President John F. Kennedy and his son, John Jr., 1963 (AP Photo) In this issue: President John F. Kennedy Zoom in on America The Life of John F. Kennedy John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born in Brookline, Massa- During WWII John applied and was accepted into the na- chusetts, on May 29, 1917 as the second of nine children vy, despite a history of poor health. He was commander of born into the family of Joseph Patrick Kennedy and Rose PT-100, which on August 2, 1943, was hit and sunk by a Fitzgerald Kennedy. John was often called “Jack”. The Japanese destroyer. Despite injuries to his back, an ail- Kennedys had a powerful impact on America. John Ken- ment that would haunt him to the end of his life, Kennedy nedy’s great-grandfather, Patrick Kennedy, emigrated managed to rescue his surviving crew members and was from Ireland to Boston in 1849 and worked as a barrel declared a “hero” by the New York Times. A year later Joe maker. His grandfather, Patrick Joseph (P.J.) Kennedy, was killed on a volunteer mission in Europe when his air- achieved success first in the saloon and liquor-import craft exploded. businesses, and then in banking. His father, Joseph Pat- Joseph Patrick now placed all his hopes on John. In 1946, rick Kennedy, made investments in banking, ship building, John F. Kennedy successfully ran for the same seat in real estate, liquor importing, and motion pictures and be- Congress, which his grandfather held nearly five decades came one of the richest men in America. -

Suspected Soviet Cell Wrote Reagan's Long-Term Strategy

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 15, Number 23, June 3, 1988 �TIillFeature Suspected Soviet cell wrote Reagan's long-tenn strategy by Jeffrey Steinberg A tightly organized cell of suspected Soviet moles wrote the Reagan administra tion's "semi-official" long-term strategy for dealing with the U.S.S.R. and also played a major hand in drafting the disastrous Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force (INF) treaty that a deluded President Reagan now hopes will earn him and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachov the Nobel Peace Prize. As shocking as this may sound, Dr. Albert Wohlstetter and Dr. Fred Ikle, the two principal authors of the presidential report, Discriminate Deterrence. have beenidentified to this news service by highly reliabJe U.S. intelligence sources as prime suspects in a Soviet-Israeli "false flag" spy ring first exposed with the November 1985 arrest of Jonathan Jay Pollard and the December 1987 arrest of Shabtai Kalmanowitch. On Feb. 19, 1988, Washington Post associate editor Bob Woodwardpublished a front-page story detailing the Pentagon and CIA's futile search for "Mr. X," the designation for a high-level intelligence community mole who was believed to be providing Pollard with top secret code numbers of classified military documents that Pollard, a counterterrorist analyst at a Naval Investigative Service facility in Suitland, Md., would then pilfer and pass on to Israeli and Soviet intelligence. Shabtai Kalmanowitch, a Russian-born Israeli multi-millionaire, soon to be tried in Israel as a KGB spy, is widely believed to have been one of the Israel-Soviet "back channels" through which the "Mr. -

1961–1963 First Supplement

THE JOHN F. KENNEDY NATIONAL SECURITY FILES USSRUSSR ANDAND EASTERNEASTERN EUROPE:EUROPE: NATIONAL SECURITY FILES, 1961–1963 FIRST SUPPLEMENT A UPA Collection from National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963 USSR and Eastern Europe First Supplement Microfilmed from the Holdings of The John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Nicholas P. Cunningham A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road • Bethesda, MD 20814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. USSR and Eastern Europe. First supplement [microform] / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels ; 35 mm. — (National security files) “Microfilmed from the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts.” Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Nicholas P. Cunningham. ISBN 1-55655-876-7 1. United States—Foreign relations—Soviet Union—Sources. 2. Soviet Union—Foreign relations—United States—Sources. 3. United States—Foreign relations—1961–1963— Sources. 4. National security—United States—History—Sources. 5. Soviet Union— Foreign relations—1953–1975—Sources. 6. Europe, Eastern—Foreign relations—1945– 1989. I. Lester, Robert. II. Cunningham, Nicholas P. III. University Publications of America (Firm) IV. Title. V. Series. E183.8.S65 327.73047'0'09'046—dc22 2005044440 CIP Copyright © 2006 LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-876-7.