Émigrés and Anglo-American Intelligence Operations in the Early Cold War Cacciatore, F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ukrainian Weekly 1979, No.21

www.ukrweekly.com I CBOEOAAXSVOBODA І Ж Щ УКРАЇНСЬКИЙ ЩОДЕННИК ^И^7 UKRAINIAN DAILY Щ UkrainiaENGLISH-LANGUAGnE WEEKLY EDITIOWeeN k 25 CENTS VOL. LXXXVI. No. 118 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, MAY 27, 1979 UNA Supreme Assembly concludes annual meeting Adopts new organizing plan, resolutions and recommendations; allocates S25,000 for national causes; awards ^23,800 in scholarships; elects Basil Tershakovec editor-in-chief .of Svoboda; plans future actions KERHONKSON,N.Y. - The Su preme Assembly of the Ukrainian National Association concluded its weeklong annual meeting here at Soyu- zivka on Saturday, May 19, and adopt ed a new organizing plan, resolutions and recommendations, voted to allo cate 525,000 for national causes, award ed 523,800 in scholarships to Ukrainian students, and elected Basil Tershakovec editor-in-chief of Svoboda. The adoption of a new organizing plan proposed by the Special Organiza tional Committee and the election of a new editor-in-chief were considered by Supreme President Dr. John O. Flis the two major topics on the agenda of the meeting. The Supreme Assembly, the associa tion's highest governing body between conventions, meets once a year at the Photo by Ihor Dlaboha UNA estate during its four-year term of Participants of the annual Supreme Assembly meeting, including the Supreme Executive Committee, the Supreme Auditing office. Committee, Supreme Advisors and honorary members. Present at the meeting, in addition to r Lozynskyj - activating more Ukraini Supreme Advisor Repeta, Supreme On Thursday, May 17, Walter Kwas, . Flis, were: Supreme Vice-President the manager of Soyuzivka, gave his Dr. Myron Kuropas, Supreme Director an youths in fraternal affairs. -

H-Diplo Roundtable, Vol. XI, No. 29

2010 H-Diplo H-Diplo Roundtable Review Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Roundtable Web/Production Editor: George Fujii Volume XI, No. 29 (2010) 10 June 2010 Sarah-Jane Corke. U.S. Covert Operations and Cold War Strategy: Truman, Secret Warfare and the CIA, 1945-53. 256 pp. London: Routledge, 2007. ISBN: 978-0-415-42077-8 (hardback, $160.00); 978-0-203-01630-5 (eBook, £80.00). Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XI-29.pdf Contents Introduction by Robert Jervis, Columbia University ................................................................. 2 Review by Betty A. Dessants, Shippensburg University ........................................................... 6 Review by Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones, University of Edinburgh....................................................... 9 Review by Scott Lucas, University of Birmingham .................................................................. 12 Review by Gregory Mitrovich, Columbia University ............................................................... 14 Response by Sarah-Jane Corke, Dalhousie University ............................................................ 20 Copyright © 2010 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For other uses, contact the H-Diplo editorial staff at [email protected]. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. XI, No. 29 (2010) Introduction by Robert Jervis, Columbia University rom the start, the role of psychological warfare and covert action has had a strange place in the historiography of the Cold War. Being surrounded by an air of mystery if F not romance, they have loomed large for the general public and the media, which alternately glamorized and demonized them. -

Memory of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in Post-Soviet Ukraine

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in History 103 Reordering of Meaningful Worlds Memory of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in Post-Soviet Ukraine Yuliya Yurchuk ©Yuliya Yurchuk, Stockholm University 2014 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 101 ISSN: 1652-7399 ISBN: 978-91-87843-12-9 Stockholm Studies in History 103 ISSN: 0491-0842 ISBN 978-91-7649-021-1 Cover photo: Barricades of Euromaidan. July 2014. Yuliya Yurchuk. Printed in Sweden by US-AB, Stockholm 2014 Distributor: Department of History In memory of my mother Acknowledgements Each PhD dissertation is the result of a long journey. Mine was not an exception. It has been a long and exciting trip which I am happy to have completed. This journey would not be possible without the help and support of many people and several institutions to which I owe my most sincere gratitude. First and foremost, I want to thank my supervisors, David Gaunt and Barbara Törnquist-Plewa, for their guidance, encouragement, and readiness to share their knowledge with me. It was a privilege to be their student. Thank you, David, for broadening the perspectives of my research and for encouraging me not to be afraid to tackle the most difficult questions and to come up with the most unexpected answers. Thank you, Barbara, for introducing me to the whole field of memory studies, for challenging me to go further in my interpretations, for stimulating me to follow untrodden paths, and for being a source of inspiration for all these years. Your encouragement helped me to complete this book. -

EUI Working Papers

ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2009/42 ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES DIASPORA POLITICS AND TRANSNATIONAL TERRORISM: AN HISTORICAL CASE STUDY Mate Nikola Tokić EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES Diaspora Politics and Transnational Terrorism: An Historical Case Study MATE NIKOLA TOKIC EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2009/42 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper, or other series, the year and the publisher. The author(s)/editor(s) should inform the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the EUI if the paper will be published elsewhere and also take responsibility for any consequential obligation(s). ISSN 1028-3625 © 2009 Mate Nikola Tokić Printed in Italy, August 2009 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), directed by Stefano Bartolini since September 2006, is home to a large post-doctoral programme. Created in 1992, it aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research and to promote work on the major issues facing the process of integration and European society. The Centre hosts major research programmes and projects, and a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. -

Revolt and Crisis in Greece

REVOLT AND CRISIS IN GREECE BETWEEN A PRESENT YET TO PASS AND A FUTURE STILL TO COME How does a revolt come about and what does it leave behind? What impact does it have on those who participate in it and those who simply watch it? Is the Greek revolt of December 2008 confined to the shores of the Mediterranean, or are there lessons we can bring to bear on social action around the globe? Revolt and Crisis in Greece: Between a Present Yet to Pass and a Future Still to Come is a collective attempt to grapple with these questions. A collaboration between anarchist publishing collectives Occupied London and AK Press, this timely new volume traces Greece’s long moment of transition from the revolt of 2008 to the economic crisis that followed. In its twenty chapters, authors from around the world—including those on the ground in Greece—analyse how December became possible, exploring its legacies and the position of the social antagonist movement in face of the economic crisis and the arrival of the International Monetary Fund. In the essays collected here, over two dozen writers offer historical analysis of the factors that gave birth to December and the potentialities it has opened up in face of the capitalist crisis. Yet the book also highlights the dilemmas the antagonist movement has been faced with since: the book is an open question and a call to the global antagonist movement, and its allies around the world, to radically rethink and redefine our tactics in a rapidly changing landscape where crises and potentialities are engaged in a fierce battle with an uncertain outcome. -

'Owned' Vatican Guilt for the Church's Role in the Holocaust?

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 4 (2009): Madigan CP 1-18 CONFERENCE PROCEEDING Has the Papacy ‘Owned’ Vatican Guilt for the Church’s Role in the Holocaust? Kevin Madigan Harvard Divinity School Plenary presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Council of Centers on Christian-Jewish Relations November 1, 2009, Florida State University, Boca Raton, Florida Given my reflections in this presentation, it is perhaps appropriate to begin with a confession. What I have written on the subject of the papacy and the Shoah in the past was marked by a confidence and even self-righteousness that I now find embarrassing and even appalling. (Incidentally, this observation about self-righteousness would apply all the more, I am afraid, to those defenders of the wartime pope.) In any case, I will try and smother those unfortunate qualities in my presentation. Let me hasten to underline that, by and large, I do not wish to retract conclusions I have reached, which, in preparation for this presentation, have not essentially changed. But I have come to perceive much more clearly the need for humility in rendering judgment, even harsh judgment, on the Catholic actors, especially the leading Catholic actors of the period. As José Sanchez, with whose conclusions in his book on understanding the controversy surrounding the wartime pope I otherwise largely disagree, has rightly pointed out, “it is easy to second guess after the events.”1 This somewhat uninflected observation means, I take it, that, in the case of the Holy See and the Holocaust, the calculus of whether to speak or to act was reached in the cauldron of a savage world war, wrought in the matrix of competing interests and complicated by uncertainty as to whether acting or speaking would result in relief for or reprisal. -

The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943 Author(S): Timothy Snyder Source: Past & Present, No

The Past and Present Society The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943 Author(s): Timothy Snyder Source: Past & Present, No. 179 (May, 2003), pp. 197-234 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3600827 . Accessed: 05/01/2014 17:29 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Oxford University Press and The Past and Present Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Past &Present. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.110.33.183 on Sun, 5 Jan 2014 17:29:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE CAUSES OF UKRAINIAN-POLISH ETHNIC CLEANSING 1943* Ethniccleansing hides in the shadow of the Holocaust. Even as horrorof Hitler'sFinal Solution motivates the study of other massatrocities, the totality of its exterminatory intention limits thevalue of the comparisons it elicits.Other policies of mass nationalviolence - the Turkish'massacre' of Armenians beginningin 1915, the Greco-Turkish'exchanges' of 1923, Stalin'sdeportation of nine Soviet nations beginning in 1935, Hitler'sexpulsion of Poles and Jewsfrom his enlargedReich after1939, and the forcedflight of Germans fromeastern Europein 1945 - havebeen retrievedfrom the margins of mili- tary and diplomatichistory. -

There Are Other Ossenkos

• TAMPA, FLORIDA TRIBUNE m. 150,478 S. 164,063 Front Edif* 0 that, P.g. Pa :,,,:+91 1, 2 1964 Date: FEB 1. There Are Other Ossenkos . Whether or not Yuri Ivanovich er notable examples are Igor Gou- Ossenko. Russian secret police zenko in Canada, 1947; Nikolay! staff officer who has sought Khokhlov, West Germany, Juri! asylum in the U.S., knows secrets Rastvorov, Japan, Peter Deriabin,' of Soviet nuclear weapons produc- Vienna, and Vadimir Petrov, Aus-: tion, as some Western sources spe- tralia, all in 1954; and Bogdon Sta. culate, his defection is a hard blow shinski, West Germany, in 1961. to Red intelligence. „CIA. Director Allen Dulles, in The idea that he may have in- his recent book, "The Craft of In- formation on atomic weapons telligence," noted that the prin- arises from the fact that Ossenko cipal value of such 'defectors was; was serving as security officer for that "one such intelligence 'volun-J the Red delegation at the Geneva teer' can literally paralyze the disarmament parley at the time of service he left behind for months his defection. to come" because of what he knows. and tells of policies, plans, current. Based on the previous pattern 9perations and secret agents. of Russian delegations to confer- That Ossenko's - value: to the ences in other countries, this meant is even greater than simply that Ossenko was a highly trusted his knOwledge of Soviet nuclear. agent detailed to keep close rein capabilities should be comforting' on the actual members of the dele- to all citizens of the U.S. -

December Layout 1

AMERICAN & INTERNATIONAL SOCIETIES FOR YAD VASHEM Vol. 41-No. 2 ISSN 0892-1571 November/December 2014-Kislev/Tevet 5775 The American & International Societies for Yad Vashem Annual Tribute Dinner he 60th Anniversary of Yad Vashem Tribute Dinner We were gratified by the extensive turnout, which included Theld on November 16th was a very memorable many representatives of the second and third generations. evening. We were honored to present Mr. Sigmund Rolat With inspiring addresses from honoree Zigmund A. Rolat with the Yad Vashem Remembrance Award. Mr. Rolat is a and Chairman of the Yad Vashem Council Rabbi Israel Meir survivor who has dedicated his life to supporting Yad Lau — the dinner marked the 60th Anniversary of Yad Vashem and to restoring the place of Polish Jewry in world Vashem. The program was presided over by dinner chairman history. He was instrumental in establishing the newly Mark Moskowitz, with the Chairman of the American Society opened Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw. for Yad Vashem Leonard A. Wilf giving opening remarks. SIGMUND A. ROLAT: “YAD VASHEM ENSHRINES THE MILLIONS THAT WERE LOST” e are often called – and even W sometimes accused of – being obsessed with memory. The Torah calls on us repeatedly and command- ingly: Zakhor – Remember. Even the least religious among us observe this particular mitzvah – a true corner- stone of our identity: Zakhor – Remember – and logically L’dor V’dor – From generation to generation. The American Society for Yad Vashem has chosen to honor me with the Yad Vashem Remembrance Award. I am deeply grateful and moved to receive this honor. -

Final Report of the Nazi War Crimes & Japanese

Nazi War Crimes & Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group Final Report to the United States Congress April 2007 Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group Final Report to the United States Congress Published April 2007 1-880875-30-6 “In a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people not to be on the side of the executioners.” — Albert Camus iv IWG Membership Allen Weinstein, Archivist of the United States, Chair Thomas H. Baer, Public Member Richard Ben-Veniste, Public Member Elizabeth Holtzman, Public Member Historian of the Department of State The Secretary of Defense The Attorney General Director of the Central Intelligence Agency Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation National Security Council Director of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Nationa5lrchives ~~ \T,I "I, I I I"" April 2007 I am pleased to present to Congress. Ihe AdnllniSlr:lllon, and the Amcncan [JeOplc Ihe Final Report of the Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Rcrords Interagency Working Group (IWG). The lWG has no\\ successfully completed the work mandated by the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act (P.L. 105-246) and the Japanese Imperial Government DisdoSUTC Act (PL 106·567). Over 8.5 million pages of records relaH:d 10 Japanese and Nazi "'ar crimes have been identifIed among Federal Go\emmelll records and opened to the pubhc. including certam types of records nevcr before released. such as CIA operational Iiles. The groundbrcaking release of Lhcse ft:cords In no way threatens lhe Malio,,'s sccurily. -

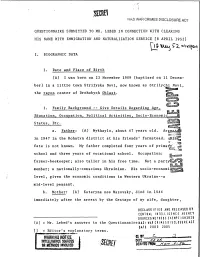

Secret Derived -From � Secret

:SEW NAZI WAR CRIMES DISCLOSURE ACT QUESTIONNAIRE SUBMITTED TO MR. LEBED IN CONNECTION WITH CLEARING HIS NAME WITH IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION SERVICE [8 APRIL 1952] rItital r uVt5iSkst: tY I. BIOGRAPHIC DATA 1. Date and Place of Birth (A) I was born on 23 November 1909 (baptised on 11 Decem- ber) in a little town Strilyska Novi, now known as Strilychi Novi, the rayon center of Drohobych Oblast. e=it fr;,N-L1 2. Family Background -- Give Details Regarding Agel. Eaml Education, Occu ation Political Activities Socio-Economic Status, Etc. afa gagE: a. Father: (A) Mykhaylo, about 67 years old. ArEgsat a.4111 in 1947 in the Rohatyn district at his friends farmstead. Oli051 Alm fate is not known. My father completed four years of primaft, Tia t-,4t. In school and three years of vocational school. Occupation: pmnots farmer-beekeeper; also tailor in his free time. Not a party041 PLihJi member; a nationally-conscious Ukrainian. His socio-economi -1747, 4 level, given the economic conditions in Western Ukraine--a mid-level peasant. b. Mother: (A) Kateryna nee Mazovsky, died in 1944 immediately after the arrest by the Gestapo of my wife, daughter, DECLASSIFIED AND RELEASED BY CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY SOURCESMETHODS EXEMPTION3B2B (A) = Mr. Lebeds answers to the QuestionnaireNAZI WAR CRIMESDISCLOSUREACT DATE 2003 2005 [] = Editors explanatory terms. ..1.10114C.N. WARNING NOTICE Ctrat It INTELLIGENCE SOURCES um OR METHODS INVOLVED ,SECRET DERIVED -FROM SECRET and family. She was about 55 years old. By birth, on her fathers side, my mother was of Polish discent. Her father was a Roman Catholic and was descended from the Polish yeomanry [nobility]; he was Ukrainianized. -

United States Department of Labor Office of Administrative Law Judges Boston, Massachusetts

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGES BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS Issue Date: 12 July 2016 ALJ NO: 2014-SPA-00004 In the Matter of JOHN R. LOFTUS, Complainant, v. HORIZON LINES, INC., Respondent, and MATSON ALASKA, INC., Successor-in-Interest. Before: Jonathan C. Calianos, Administrative Law Judge Appearances: Charles C. Goetsch, Esq., Charles C. Geotsch Law Offices, LLC, New Haven, Connecticut, for the Complainant Kevin S. Joyner, Esq., Ogletree, Deakins, Nash, Smoak & Stewart, P.C., Raleigh, North Carolina, for the Respondent DECISION AND ORDER AWARDING DAMAGES I. Statement of the Case This proceeding arises under the whistleblower protection provisions of the Seaman's Protection Act ("SPA"), 46 U.S.C. § 2114(a), as amended by Section 611 of the Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2010, P.L 111-281, and as implemented by 29 C.F.R. § 1986. On June 20, 2013, John Loftus ("Loftus" or "Complainant") filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Labor's Occupational Safety and Health Administration ("OSHA") alleging his employer, Horizon Lines, Inc. ("Horizon"), unlawfully retaliated against him. Specifically, Loftus alleges Horizon constructively discharged him for reporting to the United States Coast Guard ("USCG") and its agent, the American Bureau of Shipping ("ABS"), what he believed to be violations of maritime safety law and regulations on the ship he worked as Master. On August 6, 2014, OSHA's Assistant Regional Administrator issued an order dismissing Loftus's complaint on behalf of the Secretary of Labor ("Secretary") concluding a prior arbitration proceeding concerning the same allegations correctly resulted in Horizon's favor.