'The Future of Higher Education' Professor Sir David Cannadine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2018 Celebrating Our 45Th

Celebrating our 45th Anniversary, p. 2 Stowe Restoration Project, pgs. 3-4 The Trevelyans of Wallington Hall, pgs. 5-6 Spring 2018 1 | From the Executive Director Dear Members & Friends, THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION 20 West 44th Street, Suite 606 New York, New York 10036-6603 2018 marks Royal Oak’s 45th Anniversary. We Churchill’s studio at Chartwell give tangible 212.480.2889 | www.royal-oak.org will celebrate this in many ways—more with a expression to the many new interpretive focus on where we are as an organization today programs that will excite visitors daily just as and what we hope for in the future. the exhibition did 35 years ago. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Honorary Chairman In reviewing some of the histories of Royal Other big news for 2018 is our appeal to help Mrs. Henry J. Heinz II Oak, I was surprised to find an event in 1983 the National Trust finish off a multi-year and Chairman that was noted as pivotal in transforming multi-task restoration effort for Stowe. Stowe Lynne L. Rickabaugh the Foundation’s relationship is one of the leading garden and Vice Chairman with the Trust from one of just landscape properties in England Prof. Susan S. Samuelson growing ‘friendship’ to one of a and has a wide significance in Treasurer serious fundraising partnership. the history of garden design in Renee Nichols Tucei The connections of this historic Europe, Russia and America (see Secretary event with what Royal Oak has pages 3-4). It is among the most Thomas M. Kelly more recently accomplished and visited Trust properties. -

JOHN CRICHTON-STUART KBE, JP, MA, Honlld(Glas), Honfistructe, Honfrias, Honfcsd, Fsascot, FRSA, FCIM

JOHN CRICHTON-STUART KBE, JP, MA, HonLLD(Glas), HonFIStructE, HonFRIAS, HonFCSD, FSAScot, FRSA, FCIM John Crichton-Stuart, 6th Marquess of Bute, died on 21 July 1993 at his family home, Mount Stuart, on the Isle of Bute, aged sixty years. He was born on 27 February 1933, fifteen minutes before his twin brother David, as eldest son of the 5th Marquess of Bute and of Eileen, Marchioness of Bute, herself the younger daughter of the 8th Earl of Granard. He was educated at Ampleforth College, and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he read history. From 1947 to 1956 he was styled Earl of Dumfries, and in 1956 succeeded his father as 6th Marquess of Bute. His full titles, with the dates of their creation, were: Lord Crichton (1488), Baronet (1627), Earl of Dumfries, Viscount of Air, Lord Crichton of Sanquhar and Cumnock (1633), Earl of Bute, Viscount Kingarth, Lord Mountstuart, Cumrae and Inchmarnock (1703), Baron Mountstuart of Wortley (1761), Baron Cardiff of Cardiff Castle (1776), Earl of Windsor and Viscount Mountjoy (1796). He was Hereditary Sheriff and Coroner of the County of Bute, Hereditary Keeper of Rothesay Castle, and patron of 9 livings, but being a Roman Catholic could not present. He was Lord-Lieutenant of Bute from 1967 to 1975, and of Argyll and Bute from 1990 until his death. Even a partial list of his appointments indicates the extent of John Bute's public service. He was Convener of Buteshire County Council (1967-70), and member of the Countryside Commission for Scotland (1970-78), the Development Commission (1973-78), the Oil Development Council for Scotland (1973-78), the Council of the Royal Society of Arts (1990-92), and the Board of the British Council (1987-92). -

The Land of Israel Symbolizes a Union Between the Most Modern Civilization and a Most Antique Culture. It Is the Place Where

The Land of Israel symbolizes a union between the most modern civilization and a most antique culture. It is the place where intellect and vision, matter and spirit meet. Erich Mendelsohn The Weizmann Institute of Science is one of Research by Institute scientists has led to the develop- the world’s leading multidisciplinary basic research ment and production of Israel’s first ethical (original) drug; institutions in the natural and exact sciences. The the solving of three-dimensional structures of a number of Institute’s five faculties – Mathematics and Computer biological molecules, including one that plays a key role in Science, Physics, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology Alzheimer’s disease; inventions in the field of optics that – are home to 2,600 scientists, graduate students, have become the basis of virtual head displays for pilots researchers and administrative staff. and surgeons; the discovery and identification of genes that are involved in various diseases; advanced techniques The Daniel Sieff Research Institute, as the Weizmann for transplanting tissues; and the creation of a nanobiologi- Institute was originally called, was founded in 1934 by cal computer that may, in the future, be able to act directly Israel and Rebecca Sieff of the U.K., in memory of their inside the body to identify disease and eliminate it. son. The driving force behind its establishment was the Institute’s first president, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, a Today, the Institute is a leading force in advancing sci- noted chemist who headed the Zionist movement for ence education in all parts of society. Programs offered years and later became the first president of Israel. -

Four Corners 58

Ark The North-East Jewish community has celebrated Lord Provost, Aberdeen City the reopening of Britain’s most northerly Councillors, and the Minister for synagogue with a rededication Shabbat and an Local Government, Kevin Stewart open day for visitors. (pictured right), who is the local After the synagogue was badly damaged by a flood MSP, attended the rededication, last year, the Aberdeen community didn’t think and enjoyed the excellent range of they would be able to raise the £10 000 needed for traditional Jewish food from Mark’s repairs, but in fact their appeal raised more than Deli in Glasgow. £25 000 from donors around the world. Visitors to the building To thank the donors and everyone else who assisted were also able to see the the Community in their time of need, a special open new covers for the Bimah day was held at the synagogue following a weekend and Torah scrolls, all of of celebrations to rededicate the building. Rev which had been designed Malcolm Wiseman led the Friday night service and and embroidered by the rededication service on Shabbat. Rev Wiseman synagogue member Debby knows the Aberdeen Community well, having Taylor, and incorporated taken many services in the Synagogue in his role the names of the people and as minister to small communities. Rabbi Robert Ash organisations who helped the also joined the Community for Shabbat. Community over the past nine Members of the public, rabbis and leaders of other months, as well as Scottish Scottish communities, other religious leaders, thistles and tartan. Aberdeen’s Lord Provost Barney Crockett, the Deputy PHOTOS COURTESY OF JENNIE MILNE Enough is Enough In the wake of the unprecedented communal demonstration at Westminster to proclaim that “Enough is Enough” of antisemitism in the Labour party, leading Scottish Labour politicians approached SCoJeC to assure us of their support. -

Some Pages from the Book

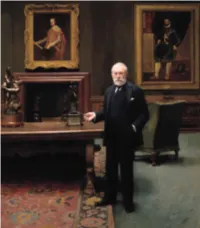

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

'^m^ ^k: UC-NRLF nil! |il!|l|ll|ll|l||il|l|l|||||i!|||!| C E 525 bm ^M^ "^ A \ THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND Of this Volume THREE HUNDRED AND Fifteen Copies have been printed, of which One Hundred and twenty are offered for sale. THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. -

ESTMINSTER UARTERLY Volume X No.4 October 2019

ESTMINSTER Volume X No.4 UARTERLY October 2019 From: The Life and Adventures of Ikey Solomons and his wife By Moses Hebron (1829) Ikey Solomons - The Real Fagin? Licoricia of Winchester The Early Jews of Oxford The Burning of Books Lifecycle events Westminster Welcomes its New Members Inside this issue Lauren Hurwitz & Timothee de Mierry Dar Utnik Yael Selfin Olivia Cohen Louise Lisztman 3 From the Rabbi Andrea Killick Gary & Robyn Mond 4 The Jews of Oxford Tally Koren 6 Justine Nahum & Simon Nicholls Licoricia of Winchester Julie Wilson 7 Simon Waley The Real Fagin? 8 Births Albert Rowe – a son for Anne & Barnaby on 13th June Amusement Arcade 9 Eliora Baroukh – a daughter for Eleanor & Benjamin on 13th July Jewish Calligraphy 10 Infant Blessings The Jewish Music Institute 11 Iris Clarfelt-Gaynor on 25th June Jack Clarfelt on 10th July Book Review 12 Balthazar Isaac Hurwitz de Mierry on 27th July Anti-Semitism in Britain 13 B’nei Mitzvah Solomon J. Solomon 14 Sophie Singer on 8th June Tesa Getter on 6th July Sir Robert Mayer 15 Sophia Matthewson on 13th July The Dorking Refugee Cttee 16 Marriages & Blessings Melisa Schindler & Jake Kahane on 26th May Park House School 17 Sam Feller & Andrea Carta on 2nd June Pioneers of WS - Mr Bradley 18 Johnny Quinn & Laura Rowland on 30th June - in Majorca Poetry Page 19 Deaths Reggie Gourgey on 4th July The Burning of Books 20 Margrit Stern on 21st August Georgina Rhodes on 10th September Editorial 22 Education Report 23 Condolences We offer sincere condolences to Gabrielle Feldman and family on the death of her father Kurt Stern on the death of his wife and to Evelyn Stern Chipperfield on the death of her mother Mark Clarfelt on the death of his sister and to Matthew, James & Emily on the death of their mother 2 From the Rabbi 4. -

The Wolfson Foundation

Thought Leader The Wolfson 65Foundation years of philanthropy An independent grant-making charity based in Central London, Wolfson Foundation has awarded some £1 billion to more than 14,000 projects in the UK from Cornwall to the Shetland Islands since its establishment in the 1950s. Chief Executive Paul Ramsbottom explains how academic decision- making is at the heart of what they do, and how they’ve adapted in the face of a global pandemic. Isaac Wolfson’s family came to Scotland as refugees in the 1890s. To give back to Wolfson Foundation have recently allocated society, the Wolfson family founded the funding to Cardiff University to create a charity in the 1950s. Research Centre on mental health. he Wolfson Foundation is a the Jewish Pale of Settlement in the grant-making charity that has 1890s and built a fortune from more Tbeen funding research and or less nothing. In the 1950s the family education in the United Kingdom for wanted to give back to British society, over 60 years. It is now facing one of and so here we are more than 60 its biggest challenges to date: the years later. What we try to do as an effect of the Coronavirus pandemic on organisation is to have all the rigour educational and cultural organisations and analysis and detachment of a across the country. Research Council but to retain that involvement and colour that comes In this interview with Chief Executive with family involvement. Paul Ramsbottom, Research Outreach found out more about the foundation’s How did you come to be involved in mission, what sort of projects it funds the foundation personally? and why, and how it is helping cultural I have been Chief Executive for Paul Ramsbottom is Chief Executive University of Edinburgh, King’s organisations in particular navigate the just over a decade. -

Cardiff 19Th Century Gameboard Instructions

Cardiff 19th Century Timeline Game education resource This resource aims to: • engage pupils in local history • stimulate class discussion • focus an investigation into changes to people’s daily lives in Cardiff and south east Wales during the nineteenth century. Introduction Playing the Cardiff C19th timeline game will raise pupil awareness of historical figures, buildings, transport and events in the locality. After playing the game, pupils can discuss which of the ‘facts’ they found interesting, and which they would like to explore and research further. This resource contains a series of factsheets with further information to accompany each game board ‘fact’, which also provide information about sources of more detailed information related to the topic. For every ‘fact’ in the game, pupils could explore: People – Historic figures and ordinary population Buildings – Public and private buildings in the Cardiff locality Transport – Roads, canals, railways, docks Links to Castell Coch – every piece of information in the game is linked to Castell Coch in some way – pupils could investigate those links and what they tell us about changes to people’s daily lives in the nineteenth century. Curriculum Links KS2 Literacy Framework – oracy across the curriculum – developing and presenting information and ideas – collaboration and discussion KS2 History – skills – chronological awareness – Pupils should be given opportunities to use timelines to sequence events. KS2 History – skills – historical knowledge and understanding – Pupils should be given -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

'The Wealth of Nations: the Health of Society': 60 Years of the Wolfson

‘The Wealth of Nations: the Health of Society’: 60 Years of the Wolfson Foundation Neil MacGregor OM, Director, The British Museum Lecture given at Wolfson College, Oxford, 8 June 2015, on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the Wolfson Foundation Janet thank you very much indeed for that generous introduction, and thank you above all for inviting me to pay tribute to the Foundation and to your father and grandfather, and what the Foundation has done and what it represents. This is as you all know a year of anniversaries, and indeed June the month of anniversaries: 800 years of Magna Carta and two hundred years since the Battle of Waterloo, which has also cast along historical shadow. It is also, and for this evening’s purposes, above all, the 60th anniversary of the creation of the Wolfson Foundation, and the history of that Foundation is in the excellent booklet that has just been published, but I would like to pay tribute to its two founding figures, its founding Chairmen: the grandfather and the father of the current Chairman, Janet Wolfson de Botton. Isaac Wolfson, who was born in poverty in Glasgow in 1897, came to London to make a fortune with Great Universal Stores, and used that fortune, as you know, to endow the Foundation. And his son, Leonard Wolfson, who continued not just GUS, but also the Foundation, developed it remarkably. I never knew Isaac Wolfson, but I did frequently meet Leonard, and was the recipient of enormous generosity and encouragement, and also extremely testing conversations. It was always the first thing: this extraordinarily generous man, already committed to helping the institution that one was trying to ask for money for, always began with a very firm and ringing endorsement that the one thing he would not pay was VAT. -

Israel, 1956-1983

MS-763: Rabbi Herbert A. Friedman Collection, 1930-2004. Series F: Life in Israel, 1956-1983. Box Folder 18 20 Keren Hayesod. British Joint Palestine Appeal. 1970-1973. For more information on this collection, please see the finding aid on the American Jewish Archives website. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 513.487.3000 AmericanJewishArchives.org British Jewry's Salute to Israel 14th December 1972 Rabbi Herb ?riedman, 15 Ibn Gvirol Street, Jerusaleo, Israel. 'l) '-". - Thank you for your kind note . Belatedly, but nonetheless wholeheartedly, I would li~:e to thank you for your help and guidance in i::iaking tb.e visit o:f our Delegation to Yad Vashe~ the most perfect and moving event I have ever been associated with. I only reGI'et that I did not have a little nore time at the Din..l'ler to exchange a few words with Frances anJ yourself. I hop e you understand. _,_,._.,, • Barzilay 0. ':> JPA, Rex House, 4-12 Regent Street, London, S.W.1. Telephone: 01 -930 5152 FOUNDER. THE LATE LORD II ARKS OF BROUGHTON tlon Pr • w"nt~. ':"Ii .. VERY REV, THE CHIEF RABB , OR. IMMANU_l o1AKOl.-"' ·"'• e.,., THE VERY REV. DR. S. GAON, B.A SIR ISAAC WOLFSON, Ban Pre$ dent. J, EDWARD SIEFF Vlce·Prasident. HYAM MORRISON Cha rman. MICHAEL M. SACHER, M.A. Deputy Chairman. I. JACK LYONS, C.B.E Vic..Clla1rnien: ROSSER CHINN, TREVOR CHINN, HAROLD H. POSTER. JOHN B. RUBENS. CYRIL STEIN Hon Treasurer· STUART YOUNG, F.C.A Director 1.AICHAEL BARZILAY. 8 Comm Exec'1t1•0 Oir&etor.