We All Global Historians Now? an Interview with David Armitage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2018 Celebrating Our 45Th

Celebrating our 45th Anniversary, p. 2 Stowe Restoration Project, pgs. 3-4 The Trevelyans of Wallington Hall, pgs. 5-6 Spring 2018 1 | From the Executive Director Dear Members & Friends, THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION 20 West 44th Street, Suite 606 New York, New York 10036-6603 2018 marks Royal Oak’s 45th Anniversary. We Churchill’s studio at Chartwell give tangible 212.480.2889 | www.royal-oak.org will celebrate this in many ways—more with a expression to the many new interpretive focus on where we are as an organization today programs that will excite visitors daily just as and what we hope for in the future. the exhibition did 35 years ago. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Honorary Chairman In reviewing some of the histories of Royal Other big news for 2018 is our appeal to help Mrs. Henry J. Heinz II Oak, I was surprised to find an event in 1983 the National Trust finish off a multi-year and Chairman that was noted as pivotal in transforming multi-task restoration effort for Stowe. Stowe Lynne L. Rickabaugh the Foundation’s relationship is one of the leading garden and Vice Chairman with the Trust from one of just landscape properties in England Prof. Susan S. Samuelson growing ‘friendship’ to one of a and has a wide significance in Treasurer serious fundraising partnership. the history of garden design in Renee Nichols Tucei The connections of this historic Europe, Russia and America (see Secretary event with what Royal Oak has pages 3-4). It is among the most Thomas M. Kelly more recently accomplished and visited Trust properties. -

Book Spring 2006.Qxd

Anthony Grafton History’s postmodern fates Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/daed/article-pdf/135/2/54/1829123/daed.2006.135.2.54.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 As the twenty-½rst century begins, his- in the mid-1980s to almost one thousand tory occupies a unique, but not an envi- now. But the vision of a rise in the num- able, position among the humanistic dis- ber of tenure-track jobs that William ciplines in the United States. Every time Bowen and others evoked, and that lured Clio examines her reflection in the mag- many young men and women into grad- ic mirror of public opinion, more voices uate school in the 1990s, has never mate- ring out, shouting that she is the ugliest rialized in history. The market, accord- Muse of all. High school students rate ingly, seems out of joint–almost as bad- history their most boring subject. Un- ly so as in the years around 1970, when dergraduates have fled the ½eld with production of Ph.D.s ½rst reached one the enthusiasm of rats leaving a sinking thousand or more per year just as univer- ship. Thirty years ago, some 5 percent sities and colleges went into economic of all undergraduates majored in histo- crisis. Many unemployed holders of doc- ry. Nowadays, around 2 percent do so. torates in history hold their teachers and Numbers of new Ph.D.s have risen, from universities responsible for years of op- a low of just under ½ve hundred per year pression, misery, and wasted effort that cannot be usefully reapplied in other careers.1 Anthony Grafton, a Fellow of the American Acad- Those who succeed in obtaining ten- emy since 2002, is Henry Putnam University Pro- ure-track positions, moreover, may still fessor of History at Princeton University and ½nd themselves walking a stony path. -

Is There a Future for Italian Microhistory in the Age of Global History?

Is There a Future for Italian Microhistory in the Age of Global History? Francesca Trivellato In the late 1970s and 80s, particularly after the appearance of Carlo Ginzburg’s The Cheese and the Worms (1976) and Giovanni Levi’s Inheriting Power (1985), Italian microhistory shook the ground of established historiographical paradigms and practices. Since then, as Anthony Grafton put it, “Microhistories have captivated readers, won places on syllabi, been translated into many languages – and enraged and delighted their [the authors’] fellow professionals” (2006, 62). Are the questions that propelled Italian microhistory still significant or have they lost impetus? How has the meaning of microhistory changed over the past thirty years? And what can this approach contribute nowadays, when ‘globalization’ and ‘global’ are the dominant keywords in the humanities and the social sciences – keywords that we hardly associate with anything micro? In what follows, I wish to put forth two arguments. I suggest that the potential of a microhistorical approach for global history remains underexploited. Since the 1980s, the encounter between Italian microhistory and global history has been confined primarily to the narrative form. A host of studies of individuals whose lives traversed multiple linguistic, political, and religious boundaries has enjoyed considerable success among scholars and the broad public alike. These are predicated on the idea that a micro- and biographical scale can best portray the entanglement of cultural traditions produced by the growing contacts and clashes between different societies that followed the sixteenth- century European geographical expansion. They also reflect a greater comfort among historians and the general reader, perhaps most pronounced in Anglophone countries, with narration rather than social scientific analysis. -

William Herle's Report of the Dutch Situation, 1573

LIVES AND LETTERS, VOL. 1, NO. 1, SPRING 2009 Signs of Intelligence: William Herle’s Report of the Dutch Situation, 1573 On the 11 June 1573 the agent William Herle sent his patron William Cecil, Lord Burghley a lengthy intelligence report of a ‘Discourse’ held with Prince William of Orange, Stadtholder of the Netherlands.∗ Running to fourteen folio manuscript pages, the Discourse records the substance of numerous conversations between Herle and Orange and details Orange’s efforts to persuade Queen Elizabeth to come to the aid of the Dutch against Spanish Habsburg imperial rule. The main thrust of the document exhorts Elizabeth to accept the sovereignty of the Low Countries in order to protect England’s naval interests and lead a league of protestant European rulers against Spain. This essay explores the circumstances surrounding the occasion of the Discourse and the context of the text within Herle’s larger corpus of correspondence. In the process, I will consider the methods by which the study of the material features of manuscripts can lead to a wider consideration of early modern political, secretarial and archival practices. THE CONTEXT By the spring of 1573 the insurrection in the Netherlands against Spanish rule was seven years old. Elizabeth had withdrawn her covert support for the English volunteers aiding the Dutch rebels, and was busy entertaining thoughts of marriage with Henri, Duc d’Alençon, brother to the King of France. Rejecting the idea of French assistance after the massacre of protestants on St Bartholomew’s day in Paris the previous year, William of Orange was considering approaching the protestant rulers of Europe, mostly German Lutheran sovereigns, to form a strong alliance against Spanish Catholic hegemony. -

| Oxford Literary Festival

OXFORD literary Saturday 30 March to festival Sunday 7 April 2019 Kazuo Ishiguro Nobel Prize Winner Dr Mary Robinson Robert Harris Darcey Bussell Mary Beard Ranulph Fiennes Lucy Worsley Ben Okri Michael Morpurgo Jo Brand Ma Jian Joanne Harris Venki Ramakrishnan Val McDermid Simon Schama Nobel Prize Winner pocket guide Box Office 0333 666 3366 • www.oxfordliteraryfestival.org Welcome to your pocket guide to the 2019 Ft Weekend oxFord literary Festival Tickets Tickets can be booked up to one hour before the event. Online: www.oxfordliteraryfestival.org In person: Oxford Visitor Information Centre, Broad Street, Oxford, seven days a week.* Telephone box office: 0333 666 3366* Festival box office: The box office in the Blackwell’s marquee will be open during the festival. Immediately before events: Last-minute tickets are available for purchase from the festival box office in the marquee in the hour leading up to each event. You are strongly advised to book in advance as the box office can get busy in the period before events. * An agents’ booking fee of £1.75 will be added to all sales at the visitor information centre and through the telephone box office. This pocket guide was correct at the time of going to press. Venues are sometimes subject to change, and more events will be added to the programme. For all the latest times and venues, check our website at www.oxfordliteraryfestival.org General enquiries: 07444 318986 Email: [email protected] Ticket enquiries: [email protected] colour denotes children’s and young people’s events Blackwell’s bookshop marquee The festival marquee is located next to the Sheldonian Theatre. -

Some Pages from the Book

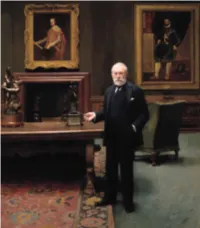

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

Invention, Memory, and Place

!"#$"%&'"()*$+',-()."/)01.2$ 34%5',6789):/;.,/)<=)>.&/ >'4,2$9)?,&%&2.1)!"@4&,-()A'1=)BC()D'=)B)6<&"%$,()BEEE8()FF=)GHIJGKB 04L1&75$/)L-9)The University of Chicago Press >%.L1$)MNO9)http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344120 322$77$/9)EHPEKPBEGE)GE9QE Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Critical Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org Invention, Memory, and Place Edward W. Said Over the past decade, there has been a burgeoning interest in two over- lapping areas of the humanities and social sciences: memory and geogra- phy or, more specifically, the study of human space. -

Hett-Syll-80020-19

The Graduate Center of the City University of New York History Department Hist 80200 Literature of Modern Europe II Thursdays 4:15-6:15 GC 3310A Prof. Benjamin Hett e-mail [email protected] GC office 5404 Office hours Thursdays 2:00-4:00 or by appointment Course Description: This course is intended to provide an introduction to the major themes and historians’ debates on modern European history from the 18th century to the present. We will study a wide range of literature, from what we might call classic historiography to innovative recent work; themes will range from state building and imperialism to war and genocide to culture and sexuality. After completing the course students should have a solid basic grounding in the literature of modern Europe, which will serve as a basis for preparation for oral exams as well as for later teaching and research work. Requirements: In a small seminar class of this nature effective class participation by all students is essential. Students will be expected to take the lead in class discussions: each week one student will have the job of introducing the literature for the week and to bring to class questions for discussion. Over the semester students will write a substantial historiographical paper (approximately 20 pages or 6000 words) on a subject chosen in consultation with me, due on the last day of class, May 13. The paper should deal with a question that is controversial among historians. Students must also submit two short response papers (2-3 pages) on readings for two of the weekly sessions of the course, and I will ask for annotated bibliographies for your historiographical papers on March 28. -

A Workshop with Jürgen Osterhammel and Geoffrey Parker Van Ittersum, Martine; Gottmann, Felicia; Mostert, Tristan

University of Dundee Writing Global History and Its Challenges - A Workshop with Jürgen Osterhammel and Geoffrey Parker Van Ittersum, Martine; Gottmann, Felicia; Mostert, Tristan Published in: Itinerario DOI: 10.1017/S0165115316000607 Publication date: 2016 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Van Ittersum, M., Gottmann, F., & Mostert, T. (2016). Writing Global History and Its Challenges - A Workshop with Jürgen Osterhammel and Geoffrey Parker. Itinerario, 40(3), 357-376. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0165115316000607 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 ‘Writing Global History and Its Challenges’ A Workshop with Jürgen Osterhammel and Geoffrey Parker University of Dundee 4 June 2016 Martine van Ittersum Felicia Gottmann Tristan Mostert Keywords Global history, history of empire, environmental history, Jürgen Osterhammel, Geoffrey Parker Abstract: On 4 June 2016, Professor Jürgen Osterhammel of the University of Konstanz and Professor Geoffrey Parker of The Ohio State University gave an all-day workshop on Global History for graduate students and junior and senior scholars of the Universities of Dundee and St. -

TRINITY COLLEGE Cambridge Trinity College Cambridge College Trinity Annual Record Annual

2016 TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge trinity college cambridge annual record annual record 2016 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2015–2016 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Contents 5 Editorial 11 Commemoration 12 Chapel Address 15 The Health of the College 18 The Master’s Response on Behalf of the College 25 Alumni Relations & Development 26 Alumni Relations and Associations 37 Dining Privileges 38 Annual Gatherings 39 Alumni Achievements CONTENTS 44 Donations to the College Library 47 College Activities 48 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 53 Field Clubs 71 Students’ Union and Societies 80 College Choir 83 Features 84 Hermes 86 Inside a Pirate’s Cookbook 93 “… Through a Glass Darkly…” 102 Robert Smith, John Harrison, and a College Clock 109 ‘We need to talk about Erskine’ 117 My time as advisor to the BBC’s War and Peace TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 3 123 Fellows, Staff, and Students 124 The Master and Fellows 139 Appointments and Distinctions 141 In Memoriam 155 A Ninetieth Birthday Speech 158 An Eightieth Birthday Speech 167 College Notes 181 The Register 182 In Memoriam 186 Addresses wanted CONTENTS TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 4 Editorial It is with some trepidation that I step into Boyd Hilton’s shoes and take on the editorship of this journal. He managed the transition to ‘glossy’ with flair and panache. As historian of the College and sometime holder of many of its working offices, he also brought a knowledge of its past and an understanding of its mysteries that I am unable to match. -

No Man's Elizabeth: Frances A. Yates and the History of History! Deanne Williams

12 No Man's Elizabeth: Frances A. Yates and the History of History! Deanne Williams "Shall we lay the blame on the war?" Virginia Woolf, A Room arOne's Own Elizabeth I didn't like women much. She had her female cousin killed, banished married ladies-in-waiting (she had some of them killed, too), and dismissed the powers and potential of half the world's population when she famously addressed the troops at Tilbury, "I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach ~f a king."z Of course, being a woman was a disappointment from the day she was born: it made her less valuable in her parents' and her nation's eyes, it diminished the status of her mother and contributed to her downfall, and it created endless complications for Elizabeth as queen, when she was long underestim ated as the future spouse of any number of foreign princes or opportunistic aristocrats and courtiers. Elizabeth saw from a very early age the precarious path walked by her father's successive wives. Under such circumstances, who would want to be female? Feminist scholars have an easier time with figures such as Marguerite de Navarre, who enjoyed a network of female friends and believed strongly in women's education; Christine de Pisan, who addressed literary misogyny head-on; or Margaret Cavendish, who embodies all our hopes for women and the sciences.3 They allow us to imagine and establish a transhistor ical feminist sisterhood. Elizabeth I, however, forces us to acknowledge the opacity of the past and the unbridgeable distance that divides us from our historical subjects. -

Annotated Guide to Secondary Literature on Medieval

THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY HIEU 390 Constantin Fasolt Fall 1999 TU TH 11:00-12:15 POLITICS, SOCIETY, AND SOCIAL THOUGHT IN EUROPE I: 400-1300 A GUIDE TO READING This guide is designed to explain my choice of readings for this course and to lead you to further readings appropriate for you, depending on how much or how little you already know about European history in general and the history of European political thought in particular. It is divided into three parts. The first part deals with general works, background information, and introductory readings of various sorts. The second part is arranged, roughly speaking, according to the topics that will be addressed in the course. The third part is a reference section, in which I simply list the most important books and articles and offer a few comments on some of them. I wrote this guide mostly for beginners. I have therefore placed special emphasis on introductory works and have tried to limit myself to works in English. But where it seemed useful or necessary I have not hesitated to mention works written in other languages. I have also made a special effort to single out books and articles that have struck me as especially telling or informative, never mind how difficult or advanced they may be. I hope that this procedure will make it easy for you to start reading where it will be most profitable for you, and to keep reading for a long time to come once your interest has been awakened. Table of Contents Part one: General works __________________________________________________ 3 A.