Adolescence and Poverty: Challenge for the 1990S. INSTITUTION Center for National Policy, Washington, DC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narratives of Interiority: Black Lives in the U.S. Capital, 1919 - 1942

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2015 Narratives of Interiority: Black Lives in the U.S. Capital, 1919 - 1942 Paula C. Austin Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/843 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] NARRATIVES OF INTERIORITY: BLACK LIVES IN THE U.S. CAPITAL, 1919 – 1942 by PAULA C. AUSTIN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 ©2015 Paula C. Austin All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________ ____________________________ Date Herman L. Bennett, Chair of Examining Committee ________________ _____________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt, Executive Office Gunja SenGupta Clarence Taylor Robert Reid Pharr Michele Mitchell Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract NARRATIVES OF INTERIORITY: BLACK LIVES IN THE U.S. CAPITAL, 1919 – 1942 by PAULA C. AUSTIN Advisor: Professor Herman L. Bennett This dissertation constructs a social and intellectual history of poor and working class African Americans in the interwar period in Washington, D.C. Although the advent of social history shifted scholarly emphasis onto the “ninety-nine percent,” many scholars have framed black history as the story of either the educated, uplifted and accomplished elite, or of a culturally depressed monolithic urban mass in need of the alleviation of structural obstacles to advancement. -

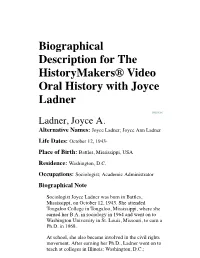

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Joyce Ladner

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Joyce Ladner PERSON Ladner, Joyce A. Alternative Names: Joyce Ladner; Joyce Ann Ladner Life Dates: October 12, 1943- Place of Birth: Battles, Mississippi, USA Residence: Washington, D.C. Occupations: Sociologist; Academic Administrator Biographical Note Sociologist Joyce Ladner was born in Battles, Mississippi, on October 12, 1943. She attended Tougaloo College in Tougaloo, Mississippi, where she earned her B.A. in sociology in 1964 and went on to Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, to earn a Ph.D. in 1968. At school, she also became involved in the civil rights movement. After earning her Ph.D., Ladner went on to teach at colleges in Illinois; Washington, D.C.; Connecticut; and Tanzania. Ladner published her first book in 1971, Tomorrow's Tomorrow: The Black Woman, a study of poor black adolescent girls from St. Louis. In 1973, Ladner joined the faculty of Hunter College at the City University of New York. Leaving Hunter College for Howard University in Washington, D.C., Ladner served as vice president for academic affairs from 1990 to 1994 and as interim president of Howard University from 1994 to 1995. In 1995, President Bill Clinton appointed her to the District of Columbia Financial Control Board, where she oversees the finances and budgetary restructuring of the public school system. She is also a senior fellow in the Governmental Studies Program at the Brookings Institution, a Washington, D.C. think tank and research organization. She has spoken nationwide about the importance of improving education for public school students. She has appeared on nationally syndicated radio and television programs as well. -

Dorie & Joyce Ladner, 2011

Dr. Joyce Ann Ladner and Ms. Doris Ann Ladner, 9-20-11 Page 1 of 73 Civil Rights History Project Interview completed by the Southern Oral History Program under contract to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History & Culture and the Library of Congress, 2011 Interviewee: Miss Dorie Ann Ladner and Dr. Joyce Ann Ladner Interview date: September 20, 2011 Location: Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Interviewer: Joseph Mosnier, Ph.D. Videographer: John Bishop Length: 2:01:26 Note: Ms. Elaine Nichols, Project Curator for the NMAAHC, was present as an observer. Comments: Only text in quotation marks is verbatim; all other text is paraphrased, including the interviewer’s questions. JOSEPH MOSNIER: Today is Tuesday, September 20, 2011. My name is Joe Mosnier of the Southern Oral History program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I’m with videographer John Bishop in Washington, D.C. at the Jefferson Building at the Library of Congress to record an oral history interview for the Civil Rights History Project, which is a joint undertaking of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Library of Congress. And we are really honored and privileged today to have with us Miss Doris Ann Ladner. DORIS ANN LADNER: Dorie. 1 Dr. Joyce Ann Ladner and Ms. Doris Ann Ladner, 9-20-11 Page 2 of 73 JM: Dorie Ladner, and, uh, Dr. Joyce Ladner, sisters, um, originally from Mississippi who have had – JOYCE ANN LADNER: Joyce Ann as well. JM: Joyce Ann as well. Uh, long, long histories of involvement in progressive struggle in the Movement and, uh, let me note as well, we’re delighted to have with us Elaine Nichols, who is the project curator at the museum. -

“Two Voices:” an Oral History of Women Communicators from Mississippi Freedom Summer 1964 and a New Black Feminist Concept ______

THE TALE OF “TWO VOICES:” AN ORAL HISTORY OF WOMEN COMMUNICATORS FROM MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM SUMMER 1964 AND A NEW BLACK FEMINIST CONCEPT ____________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________________________ by BRENDA JOYCE EDGERTON-WEBSTER Dr. Earnest L. Perry Jr., Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2007 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled: THE TALE OF “TWO VOICES:” AN ORAL HISTORY OF WOMEN COMMUNICATORS FROM MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM SUMMER 1964 AND A NEW BLACK FEMINIST CONCEPT presented by Brenda Joyce Edgerton-Webster, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Earnest L. Perry, Jr. Dr. C. Zoe Smith Dr. Carol Anderson Dr. Ibitola Pearce Dr. Bonnie Brennen Without you, dear Lord, I never would have had the strength, inclination, skill, or fortune to pursue this lofty task; I thank you for your steadfast and graceful covering in completing this dissertation. Of greatest importance, my entire family has my eternal gratitude; especially my children Lauren, Brandon, and Alexander – for whom I do this work. Special acknowledgements to Lauren who assisted with the audio and video recording of the oral interviews and often proved herself key to keeping our home life sound; to my fiancé Ernest Evans, Jr. who also assisted with recording interviews and has supported me in every way possible from beginning to end; to my late uncle, Reverend Calvin E. -

For a PDF Version of the May 2020 Issue, Please Click Here

The Sociologist May 2020 On the Cover: Collage of past and present sociologists and inscription of the aspiration of CONTENTS public sociology. Created by Emily McDonald. 3 The Challenge of Public Sociology – in the Pandemic of 2020 Contributors 5 Aldon Morris The Sociology of W.E.B. Du Bois: Britany Gatewood The Centrality of Historically Alexandra Rodriguez Black Colleges and Universities Marie Plaisime Melissa Gouge Andrea Robles 13 Rutledge M. Dennis Truth and Service: The Hundred- Kimya N. Dennis Year Legacy of Sociology at Howard University 19 The Sociologist is published two times a year by the District of Columbia Sociological Participatory Action Research as Society (DCSS) in partnership with the Public Sociology: Bringing Lived George Mason University Department of Experience Back In Sociology and Anthropology. Editors: Amber Kalb, Emily McDonald, Briana Pocratsky, Yoku Shaw-Taylor, Maria Valdovinos, Margaret Zeddies. 27 W.E.B. Du Bois, the First Public Sociologist thesociologistdc.com dcsociologicalsociety.org 36 Ask Us 2 Colleges and Universities,” Aldon Morris The Challenge of Public highlights the central role played by W.E.B. Sociology – in the Du Bois, other early African American sociologists, and Historically Black Colleges Pandemic of 2020 and Universities (HBCUs) in challenging the blatant and institutional racism that was Amber Kalb foundational to the discipline of sociology. In Emily McDonald “W.E.B. Du Bois, the First Public Briana Pocratsky Sociologist,” Rutledge M. Dennis and Kimya Maria Valdovinos N. Dennis work to reframe our understanding Margaret Zeddies of W.E.B. Du Bois, positioning him as the first public sociologist. This issue is the product of a collaborative Beyond Burawoy, sociologists such effort of doctoral students in the public as Du Bois demonstrate the commitment and sociology PhD program at George Mason tenacity with which the founders of sociology University. -

Academic Program Journal Hallowed Grounds: Sites of African American Memory

101st Annual Meeting and Conference Academic Program Journal Hallowed Grounds: Sites of African American Memory October 5-9, 2016 Richmond Marriott • Richmond, Virginia www.asalh.org Association for the Study of African American Life and History 2017 Call for Papers The Crisis in Black Education 102nd Annual Meeting and Conference September 27 – October 1, 2017 Hilton Cincinnati • Netherland Plaza Hotel The theme for 2017 focuses on the crucial role of education in the history of African Americans. ASALH’s founder Carter G. Woodson once wrote that “if you teach the Negro that he has accomplished as much good as any other race he will aspire to equality and justice without regard to race.” Woodson understood well the implications associated with the denial of access to knowledge, and he called attention to the crisis that resulted from persistently imposed racial barriers to equal education. The crisis in black education first began in the days of slavery when it was unlawful for slaves to learn to read and write. In pre-Civil War northern cities, free blacks were forced as children to walk long distances past white schools on their way to the one school relegated solely to them. Whether by laws, policies, or practices, racially separated schools remained the norm in America from the late nineteenth century well into our own time. Throughout the last quarter of the twentieth century and continuing today, the crisis in black education has grown significantly in urban neighborhoods where public schools lack resources, endure overcrowding, exhibit a racial achievement gap, and confront policies that fail to deliver substantive opportunities. -

Sweating the Small Stuff Inner-City Schools and the New Paternalism

Sweating the Small Stuff Inner-City Schools and the New Paternalism Sweating the Small Stuff Inner-City Schools and the New Paternalism David Whitman Thomas B. Fordham Institute June 2008 Copyright © 2008 by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute Published by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute Press 1016 16th Street NW, 8th Floor Washington, D.C. 20036 www.edexcellence.net [email protected] (202) 223-5452 The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is a nonprofit organization that conducts research, issues publications, and directs action projects in elementary/secondary education reform at the national level and in Ohio, with special emphasis on our hometown of Dayton. It is affiliated with the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. Further information can be found at www.edexcellence.net, or by writing to the Institute at 1016 16th St. NW, 8th Floor, Washington, D.C. 20036. The report is available in full on the Institute’s website; additional copies can be ordered at www.edexcellence.net. The Institute is neither connected with nor sponsored by Fordham University. ISBN: 978-0-615-21408-5 Text set in Adobe Garamond and Scala Design by Alton Creative, Inc. Printed and bound by Chroma Graphics in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Lynn and Lily Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................. ix Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Chapter One: The Achievement Gap and Education Reform -

American Sociological Association 1722 N Street, NW Washington, DC

Lester F. Ward Ellsworth Faris Everett C. Hughes William G. Sumner Frank H. Hankins George C. Homans Franklin H. Giddings Edwin H. Sutherland Pitirim A. Sorokin Albion W. Small Robert M. Maciver Wilbert E. Moore Edward A. Ross Stuart A. Queen Charles P. Loomis George E. Vincent Dwight Sanderson Philip M. Hauser George E. Howard George A. Lundberg Arnold M. Rose Charles H. Cooley Rupert B. Vance Ralph H. Turner Frank W. Blackmar Kimball Young Reinhard Bendix James Q. Dealey Carl C. Taylor William H. Sewell Edward C. Hayes Louis Wirth William J. Goode James P. Lichtenberger E. Franklin Frazier Mirra Komarovsky Ulysses G. Weatherly Talcott Parsons Peter M. Blau Charles A. Ellwood Leonard S. Cottrell, Jr. Lewis M. Coser Robert E. Park Robert C. Angell Alfred McClung Lee John L Gillin Dorothy Swaine Thomas J. Milton Yinger William I. Thomas Samuel A. Stouffer Amos H. Hawley John M. Gillette Florian Znaniecki Hubert M. Blalock, Jr. William F. Ogburn Donald Young Peter H. Rossi Howard W. Odum Herbert Blumer William Foote Whyte Emory S. Borgardus Robert K. Merton Erving Goffman Luther L. Bernard Robin M. Williams, Jr. Alice S. Rossi Edward B. Reuter Kingsley Davis James F. Short, Jr. Ernest W. Burgess Howard Becker Kai Erikson F. Stuart Chapin Robert E. L. Faris Matilda White Riley Henry P. Fairchild Paul F. Lazarsfeld American Sociological Association 1722 N Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20036 (202) 833-341 0 (Printed in the USA.) COVER DESIGN by Karen Gray Edwards Th~ time has long passed, if it ever existed, when it is sensible to generalize from findings based on studies done entirely within the · UnitEid States, without asking whether our findings are descriptive only of the U.S: or would apply as well to other developed countries, to other Western countries, to other capitalist countries, to other countries in gene~al. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E2384 HON

E2384 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks December 20, 2001 our civil servants taught us anything on Sep- accomplished residents of the District of Co- rowing and clean audits has been achieved. tember 11, 2001, it is that this badge is a sym- lumbia. The huge task of restructuring and reforming bol of heroism and honor. I know that he will This year, the Authority completed six years each city agency is proceeding with many no- wear it with pride. that have brought the District of Columbia out table improvements. The Authority, working f of the worst financial crisis in a century. To with elected officials has improved the most cope with this crisis, Congress passed the critical agencies, including public safety and HONORING COPELAND AND WI- District of Columbia Financial Responsibility education, where resident concern was pro- NONA GRISWOLD ON THEIR 50TH and Management Assistance Authority Act in nounced. These financial and management WEDDING ANNIVERSARY 1995. The city had followed several others— improvements are among the many rich fea- Philadelphia, New York, and Cleveland among tures of the Authority’s legacy, HON. JEFF MILLER them—to junk bond status indicating an inabil- However, the Authority also left an important OF FLORIDA ity to borrow, or insolvency. As with the cities warning not only for the city but for Congress IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES that preceded them, the District required a about the future of the city. Despite remark- ‘‘control board’’ or Authority in order to con- able city improvements and the Revitalization Thursday, December 20, 2001 tinue to borrow the necessary money to func- Act’s assumption of $5 billion in pension liabil- Mr. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Joyce Ladner

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Joyce Ladner Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Ladner, Joyce A. Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Joyce Ladner, Dates: June 11, 2003 and June 9, 2003 Bulk Dates: 2003 Physical 13 Betacame SP videocasettes (6:18:51). Description: Abstract: Sociologist and academic administrator Joyce Ladner (1943 - ) is the former vice president of academic affairs and interim president of Howard University, and a senior fellow for the Brookings Institute in Governmental Affairs. She has served on the District of Columbia Financial Control Board, overseeing budgetary restructuring of the public school system. Ladner was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on June 11, 2003 and June 9, 2003, in Washington, District of Columbia. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2003_128 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Sociologist Joyce Ladner was born in Battles, Mississippi, on October 12, 1943. She attended Tougaloo College in Tougaloo, Mississippi, where she earned her B.A. in sociology in 1964 and went on to Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, to earn a Ph.D. in 1968. At school, she also became involved in the civil rights movement. After earning her Ph.D., Ladner went on to teach at colleges in Illinois; Washington, D.C.; Connecticut; and Tanzania. Ladner published her first book in 1971, Tomorrow's Tomorrow: The Black Woman, a study of poor black adolescent girls from St. -

The Hilltop 4-8-1994

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University The iH lltop: 1990-2000 The iH lltop Digital Archive 4-8-1994 The iH lltop 4-8-1994 Hilltop Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_902000 Recommended Citation Staff, Hilltop, "The iH lltop 4-8-1994" (1994). The Hilltop: 1990-2000. 112. https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_902000/112 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The iH lltop Digital Archive at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH lltop: 1990-2000 by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I,.; "~) t~ ~ ~ ,ta. ii" . [ ,,l~ '•~411 \C, ""~'' ume 77, No.25 Serving the Howard University community since 1924 April 8, 1994 ---- _: '.THE HILLTOP.. Howard University 1nourns death .. ' ---- ; . I ·, •. \' ' ' THIS WEEK of 1n11rdered engineering student ~--- By Shunl OuBone dayi, before Sansbury's death. WHO Y()U CALLIN A ... ? HdltOp Staff 'M'rter .. I begged her to leave htm. alone. He w·.i., withdrawn and never look~'d lrina Ch.1nel San.'ibUI); a 22-year O\VARD UNIVERSITY ATHLETIC you in !he face. I le \\'al, a very jealous old I Inward Uni,1:r.i1y student. had person, c.xtremcly jealous." she said. ~~.,raECTOR CAUGHT IN VERBAL high hope,, of becoming an electrical 8~: David Simmons has been accused of engineer al Pep<."O Power Company Sarn,bury·~ aunt Francina described lhng members of the cheerling team a nexl year. San.,t,w-y wa., one !-Cme~ter her niece as a "high-spirited person ,hy ofgr.1dualing when all her dreams who nc\'er torgot birlhdays or C'hri,1- -:-.. -

C-SPAN3 Features Civil Rights Pioneers in Their

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture C-SPAN3 Features Civil Rights Pioneers In Their Own Words As Recorded by the National Museum of African American History and Culture August 19-23, 2013 at 8pm ET on C-SPAN3’s American History TV In collaboration with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, C-SPAN3’s American History TV presents the eyewitness accounts of the men and women who carried the civil rights movement forward through the tumultuous decades of the 1950s and 1960s. Their stories are televised for the first time on C-SPAN3. As the country marks the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington this August, American History TV brings the voices and stories of the civil rights movement to a national audience with five nights of prime time programming starting at 8pm on August 19. Hear from… August 19 at 8pm ET Joseph Lowery who describes how he was forced to hide in a Montgomery, Alabama hotel from the Ku Klux Klan just as he, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and others worked to create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in hopes of taking the civil rights movement nationwide. August 20 at 8pm ET Freeman Hrabowski – now the president of the University of Maryland Baltimore County – who recalls Dr. King’s 1963 appeal to children to march for civil rights and how, at 12, he answered the call only to be forced into a police wagon, detained behind bars in a juvenile facility and separated for five days from his parents.