Dorie & Joyce Ladner, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Interview with Dorie Ann Ladner Emilye Crosby

“I Just Had a Fire!”: An Interview with Dorie Ann Ladner Emilye Crosby The Southern Quarterly, Volume 52, Number 1, Fall 2014, pp. 79-110 (Article) Published by The University of Southern Mississippi, College of Arts and Sciences For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/567251 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] VOL. 52, NO. 1 (FALL 2014) 79 “I Just Had a Fire!”: An Interview with Dorie Ann Ladner* EMILYE CROSBY Although I didn’t meet Dorie Ladner until April 2010, she helped shape the world that I grew up in. She and others in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) were the “shock troops,” the cutting edge of the civil rights movement. Founded out of the 1960 sit-ins, the young people in SNCC led the way in challenging and defeating segregation in public accommodations. They also moved into rural southern communities, organizing and working with local residents on registering to vote, trying to breathe life into what was ostensibly a constitutionally-protected right. Born and raised in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, by the time Dorie and her younger sister Joyce Ladner encountered the sit-in movement in their fi rst year of college at Jackson State, they already had years of experience attending meetings of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). They were mentored by three men who would eventually lose their lives as a result of their civil rights activism: Medgar Evers, Clyde Kennard, and Vernon Dahmer.1 Dorie Ladner describes being deeply affected by the murder of Emmett Till, and it seems almost preordained that she would join the emerging student movement at the fi rst opportunity. -

Narratives of Interiority: Black Lives in the U.S. Capital, 1919 - 1942

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2015 Narratives of Interiority: Black Lives in the U.S. Capital, 1919 - 1942 Paula C. Austin Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/843 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] NARRATIVES OF INTERIORITY: BLACK LIVES IN THE U.S. CAPITAL, 1919 – 1942 by PAULA C. AUSTIN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 ©2015 Paula C. Austin All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________ ____________________________ Date Herman L. Bennett, Chair of Examining Committee ________________ _____________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt, Executive Office Gunja SenGupta Clarence Taylor Robert Reid Pharr Michele Mitchell Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract NARRATIVES OF INTERIORITY: BLACK LIVES IN THE U.S. CAPITAL, 1919 – 1942 by PAULA C. AUSTIN Advisor: Professor Herman L. Bennett This dissertation constructs a social and intellectual history of poor and working class African Americans in the interwar period in Washington, D.C. Although the advent of social history shifted scholarly emphasis onto the “ninety-nine percent,” many scholars have framed black history as the story of either the educated, uplifted and accomplished elite, or of a culturally depressed monolithic urban mass in need of the alleviation of structural obstacles to advancement. -

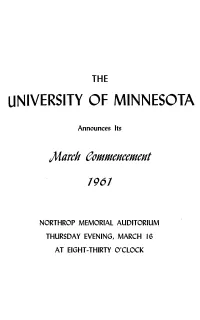

University of Minnesota

THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Announces Its ;Uafclt eommellcemellt 1961 NORTHROP MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 16 AT EIGHT-THIRTY O'CLOCK Univcrsitp uf Minncsuta THE BOARD OF REGENTS Dr. O. Meredith Wilson, President Mr. Laurence R. Lunden, Secretary Mr. Clinton T. Johnson, Treasurer Mr. Sterling B. Garrison, Assistant Sccretary The Honorable Ray J. Quinlivan, St. Cloud First Vice President and Chairman The Honorable Charles W. Mayo, M.D., Rochester Second Vice President The Honorable James F. Bell, Minneapolis The Honorable Edward B. Cosgrove, Le Sueur The Honorable Daniel C. Gainey, Owatonna The Honorable Richard 1. Griggs, Duluth The Honorable Robert E. Hess, White Bear Lake The Honorable Marjorie J. Howard (Mrs. C. Edward), Excelsior The Honorable A. I. Johnson, Benson The Honorable Lester A. Malkerson, Minneapolis The Honorable A. J. Olson, Renville The Honorable Herman F. Skyberg, Fisher As a courtesy to those attending functions, and out of respect for the character of the building, be it resolved by the Board of Regents that there be printed in the programs of all functions held in Cyrus Northrop Memorial Auditorium a request that smoking be confined to the outer lobby on the main floor, to the gallery lobbies, and to the lounge rooms, and that members of the audience be not allowed to use cameras in the Auditorium. r/tis Js VOUf UnivcfsilU CHARTERED in February, 1851, by the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Minnesota, the University of Minnesota this year celebrated its one hundred and tenth birthday. As from its very beginning, the University is dedicated to the task of training the youth of today, the citizens of tomorrow. -

Mississippi Freedom Summer: Compromising Safety in the Midst of Conflict

Mississippi Freedom Summer: Compromising Safety in the Midst of Conflict Chu-Yin Weng and Joanna Chen Junior Division Group Documentary Process Paper Word Count: 494 This year, we started school by learning about the Civil Rights Movement in our social studies class. We were fascinated by the events that happened during this time of discrimination and segregation, and saddened by the violence and intimidation used by many to oppress African Americans and deny them their Constitutional rights. When we learned about the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964, we were inspired and shocked that there were many people who were willing to compromise their personal safety during this conflict in order to achieve political equality for African Americans in Mississippi. To learn more, we read the book, The Freedom Summer Murders, by Don Mitchell. The story of these volunteers remained with us, and when this year’s theme of “Conflict and Compromise” was introduced, we thought that the topic was a perfect match and a great opportunity for us to learn more. This is also a meaningful topic because of the current state of race relations in America. Though much progress has been made, events over the last few years, including a 2013 Supreme Court decision that could impact voting rights, show the nation still has a way to go toward achieving full racial equality. In addition to reading The Freedom Summer Murders, we used many databases and research tools provided by our school to gather more information. We also used various websites and documentaries, such as PBS American Experience, Library Of Congress, and Eyes on the Prize. -

Accessions: 2001-2002

The Primary Source Volume 24 | Issue 2 Article 8 2002 Accessions: 2001-2002 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/theprimarysource Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation (2002) "Accessions: 2001-2002," The Primary Source: Vol. 24 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. DOI: 10.18785/ps.2402.08 Available at: https://aquila.usm.edu/theprimarysource/vol24/iss2/8 This Column is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in The rP imary Source by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Preservation Assistance Grants The National Endowment for the Humanities, Division of Preservation and Access, is in its fourth year of awarding small grants, of up to $5000, to help libraries, archives, museums and historical organizations · enhance their capacity to preserve their humanities collections. Applicants may request support for general preservation assessments or consultations with preservation professionals to develop a specific plan for addressing an identified problem. Institutions may also apply for funding to attend prese1vation training workshops and to purchase basic preservation supplies, equipment, and storage furniture. The deadline for the 2003 Preservation Assistance Grants is approaching. Applications are due by May 15, 2003. For more information and updates on the guidelines, see the NEH website http://www.neh.gov/grants/guidelines/presassistance.html 2002-03 NEH Preservation Assistance Grant Recipients Announced In 2000 the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) began awarding these small preservation grants to libraries, archives, museums, and historical organizations. -

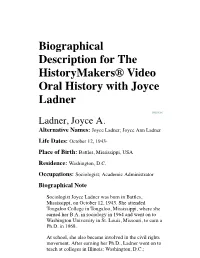

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Joyce Ladner

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Joyce Ladner PERSON Ladner, Joyce A. Alternative Names: Joyce Ladner; Joyce Ann Ladner Life Dates: October 12, 1943- Place of Birth: Battles, Mississippi, USA Residence: Washington, D.C. Occupations: Sociologist; Academic Administrator Biographical Note Sociologist Joyce Ladner was born in Battles, Mississippi, on October 12, 1943. She attended Tougaloo College in Tougaloo, Mississippi, where she earned her B.A. in sociology in 1964 and went on to Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, to earn a Ph.D. in 1968. At school, she also became involved in the civil rights movement. After earning her Ph.D., Ladner went on to teach at colleges in Illinois; Washington, D.C.; Connecticut; and Tanzania. Ladner published her first book in 1971, Tomorrow's Tomorrow: The Black Woman, a study of poor black adolescent girls from St. Louis. In 1973, Ladner joined the faculty of Hunter College at the City University of New York. Leaving Hunter College for Howard University in Washington, D.C., Ladner served as vice president for academic affairs from 1990 to 1994 and as interim president of Howard University from 1994 to 1995. In 1995, President Bill Clinton appointed her to the District of Columbia Financial Control Board, where she oversees the finances and budgetary restructuring of the public school system. She is also a senior fellow in the Governmental Studies Program at the Brookings Institution, a Washington, D.C. think tank and research organization. She has spoken nationwide about the importance of improving education for public school students. She has appeared on nationally syndicated radio and television programs as well. -

Adolescence and Poverty: Challenge for the 1990S. INSTITUTION Center for National Policy, Washington, DC

DOCUMSNT RESUME ED 347 229 UD 028 687 AUTHOR Edelman, Peter B., Ed.; Ladner, Joyce, Ed. TITLE Adolescence and Poverty: Challenge for the 1990s. INSTITUTION Center for National Policy, Washington, DC. REPORT NO ISBN-0-944237-32-0 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 167p. AVAILABLE FrOM University Press of America, Inc., 4720 Boston Way, Lanham, ND 20706 (paperISBN-0-944237-32-0; ISBN-0-944237-31-2--hardback). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Collected WOrks - General (020) -- Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Development; *Adolescents; Black Youth; Cultural Background; *Disadvantaged Youth; Early Parenthood; *Economically Disadvantaged; Educational Policy; Elementary Secondary Education; Futures (of Society); Minority Group Children; *Poverty; Sex Differences; Social Change; *Social Problems; *Urban Youth ABSTRACT The current situation for poor adolescents in the United States is reviewed in this collection of essays, and some strategies and insights for policymakers are presented. The essays of this volume cover the basic interactions of adolescence and poverty from theoretical and anecdotal perspectives. Critical issues of education and employment are discussed, and separate assessments of the difficulties facing poor girls and poor boys in adolescence are provided. After an introduction by Peter B. Edelman and Joyce Ladner, the following essays are included: !I) "Growing Up in America" (R. Coles); (2) "The Logic of Adolescence" (L. Streinberg); (3) "The Adolescent Poor and the Transition to Early Adulthood" (A. M. Sum and W. N. Fogg); (4) "The High-Stakes Challenge of Programs for Adolescent Mothers" (J. S. Musick); and (5) "Poverty and Adolescent Black Males: The Subculture of Disengagement" (R. -

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid 5.20

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid 5.20 OFFICE OF SECRETARY OF STATE COMMISSIONS PARDONS, 1836- Abstract: Pardons (1836-2018), restorations of citizenship, and commutations for Missouri convicts. Extent: 66 cubic ft. (165 legal-size Hollinger boxes) Physical Description: Paper Location: MSA Stacks ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Alternative Formats: Microfilm (S95-S123) of the Pardon Papers, 1837-1909, was made before additions, interfiles, and merging of the series. Most of the unmicrofilmed material will be found from 1854-1876 (pardon certificates and presidential pardons from an unprocessed box) and 1892-1909 (formerly restorations of citizenship). Also, stray records found in the Senior Reference Archivist’s office from 1836-1920 in Box 164 and interfiles (bulk 1860) from 2 Hollinger boxes found in the stacks, a portion of which are in Box 164. Access Restrictions: Applications or petitions listing the social security numbers of living people are confidential and must be provided to patrons in an alternative format. At the discretion of the Senior Reference Archivist, some records from the Board of Probation and Parole may be restricted per RSMo 549.500. Publication Restrictions: Copyright is in the public domain. Preferred Citation: [Name], [Date]; Pardons, 1836- ; Commissions; Office of Secretary of State, Record Group 5; Missouri State Archives, Jefferson City. Acquisition Information: Agency transfer. PARDONS Processing Information: Processing done by various staff members and completed by Mary Kay Coker on October 30, 2007. Combined the series Pardon Papers and Restorations of Citizenship because the latter, especially in later years, contained a large proportion of pardons. The two series were split at 1910 but a later addition overlapped from 1892 to 1909 and these records were left in their respective boxes but listed chronologically in the finding aid. -

Index to Applicants in Marriage Application Books for Hendricks County, Indiana (1905-1950)

Index to Applicants in Marriage Application Books for Hendricks County, Indiana (1905-1950) Indexed by Meredith Thompson Avon, Indiana 2015 NOTE: This index is not meant to be a comprehensive listing of all the information that was included in the marriage application—you should always consult the actual entry in the marriage application book. BACKGROUND: In May 1905, a new Indiana law took effect, requiring the recording of detailed information about the bride and groom (such as their birthdates and birthplaces, as well as their occupations and information about any previous marriages) as well as information about their parents. In Hendricks County, the information from the marriage applications was initially kept in a separate set of books from the marriage record (which only recorded the names of the bride and groom, the date the marriage was performed, and the name of the person who performed the marriage). This separate set of marriage application books was used in Hendricks County from May 1905 through May 1950; then beginning in June 1950, the application information was recorded in the same set of books as the marriage record. The Archives section of the Hendricks County Government website (www.co.hendricks.in.us) has digital versions of these 1905-1950 marriage application books. The digital versions are also available as part of an Indiana marriage database on FamilySearch (www.familysearch.org). Additionally, these marriage application books have been microfilmed, and that microfilm is available locally at the Plainfield library, as well as the Indiana State Library in Indianapolis and the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah. -

Extensions of Remarks E1629 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

September 6, 2006 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1629 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS HONORING VICTORIA GRAY ADAMS HONORING LOUIS LAFAYETTE PAYING TRIBUTE TO NEVADA CIVIL RIGHTS LEGEND HUNTLEY STATE COLLEGE AND DR. FRED MARYANSKI HON. BENNIE G. THOMPSON OF MISSISSIPPI HON. ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN HON. JON C. PORTER IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF FLORIDA OF NEVADA Wednesday, September 6, 2006 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Mr. THOMPSON of Mississippi. Mr. Speak- Wednesday, September 6, 2006 er, I would like to recognize the life of an Afri- Wednesday, September 6, 2006 Mr. PORTER. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to can-American civil rights legend, Mrs. Victoria Ms. ROS-LEHTINEN. Mr. Speaker, I would honor the students, faculty and administrators Gray Adams. Victoria Gray Adams, civil rights of Nevada State College’s School of Nursing activist, co-founded the Mississippi Freedom like to honor a great man whose life rep- resents an American success story. Sadly, in Henderson, Nevada, for their tremendous Democratic Party. achievements with their accelerated nursing Victoria Gray Adams and fellow civil rights Louis Lafayette Huntley passed away, but he program. Their achievements are a reflection activist Fannie Lou Hamer and Annie Devine left behind a legacy of service for generations of their commitment to our community. Dr. were chosen as the national spokespersons to follow. Mr. Huntley’s life is a testament to Fred Maryanski, President of Nevada State for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party commitment, faith and perseverance. College, has been instrumental in Nevada and attended the 1964 Democratic Convention Louis Huntley grew up in a large family in State College’s early success as Nevada’s in Atlantic City, New Jersey. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Dorie Ladner

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Dorie Ladner PERSON Ladner, Dorie, 1942- Alternative Names: Dorie Ladner; Life Dates: June 28, 1942- Place of Birth: Hattiesburg, Mississippi, USA Residence: Washington, D.C. Occupations: Civil Rights Activist; City Social Service Worker Biographical Note Civil rights activist Dorie Ann Ladner was born on June 28, 1942, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. As an adolescent, she became involved in the NAACP Youth Chapter where Clyde Kennard served as advisor. Ladner got involved in the Civil Rights Movement and wanted to be an activist after hearing about the murder of Emmitt Till. After graduating from Earl Travillion High School as salutatorian, alongside her sister, Joyce Ladner, she went on to enroll at Jackson State University. Dedicated to the fight for civil rights, Ladner, she went on to enroll at Jackson State University. Dedicated to the fight for civil rights, during their freshmen year at Jackson State, she and her sister attended state NAACP meetings with Medgar Evers and Eileen Beard. That same year, Ladner was expelled from Jackson State for participating in a protest against the jailing of nine students from Tougaloo College. In 1961, Ladner enrolled at Tougaloo College where she became engaged with the Freedom Riders. During the early 1960s, racial hostilities in the South caused Ladner to drop out of school three times to join the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In 1962, she was arrested along with Charles Bracey, a Tougaloo College student, for attempting to integrate the Woolworth’s lunch counter. She joined with SNCC Project Director Robert Moses and others from SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to register disenfranchised black voters and integrate public accommodations. -

The African-American Freedom Movement Through the Lens of Gandhian Nonviolence

The African-American Freedom Movement Through the Lens of Gandhian Nonviolence Chris Moore-Backman May 2011 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Self-Designed Masters Degree Program Lesley University Specialization: Nonviolence and Social Change FREEDOM MOVEMENT THROUGH GANDHIAN LENS i Abstract This thesis explores the meaning and application of the three definitive aspects of the Gandhian approach to nonviolence—personal transformation, constructive program (work of social uplift and renewal), and political action, then details the African-American Freedom Movement’s unique expression of and experimentation within those three spheres. Drawing on an in-depth review of historical, theoretical, and biographical literature, and an interview series with six living contemporaries of Martin Luther King Jr., the study highlights key similarities between the nonviolence philosophies and leadership of Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., as well as similarities between the movements of which these leaders were a part. Significant differences are also noted, such as the African-American Freedom Movement’s relative lack of focused and systematized implementation of a constructive program along Gandhian lines. The study illustrates the degree to which the African-American Freedom Movement manifested Gandhian principles and practices, while also suggesting that contemporary nonviolence practitioners can identify ways in which the Gandhian approach can be more fully adopted. FREEDOM MOVEMENT THROUGH GANDHIAN