Expertcommittee.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2016

BRINGING THE WORLD TO INDIA Annual Report 2016 Observer Research Foundation (ORF) seeks to lead and aid policy thinking towards building a strong and prosperous India in a fair and equitable world. It sees India as a country poised to play a leading role in the knowledge age—a role in which it shall be increasingly called upon to proactively ideate in order to shape global conversations, even as it sets course along its own trajectory of long-term sustainable growth. ORF helps discover and inform India’s choices. It carries Indian voices and ideas to forums shaping global debates. It provides non-partisan, independent, well-researched analyses and inputs to diverse decision-makers in governments, business communities, academia, and to civil society around the world. Our mandate is to conduct in-depth research, provide inclusive platforms and invest in tomorrow’s thought leaders today. Ideas l Forums l Leadership l Impact message from the CHAIRMAN 3 Bharat Goenka message from the DIRECTOR 5 Sunjoy Joshi 9 PROGRAMMES & INITIATIVES 43 FORUMS 51 PUBLICATIONS message from the VICE PRESIDENT 62 Samir Saran Contents 65 FINANCIAL FACTSHEET 68 List of EVENTS 74 List of PUBLICATIONS ANNEX 79 List of FACULTY 67 84 ORF THEMATIC TREE ORF is paying special attention to the intellectual depth of its work and enhancing the ability to deliver products and services efficiently. We are also endeavouring to further extend the reach among the policy makers, academics and business leaders worldwide. —late shri r.k. mishra 1 Message from the Chairman bharat goenka t the end of a journey of over ORF hosted over 240 interactions, a quarter century, even as discussions, roundtables and conferences AI extend my greetings to all on contemporary policy questions. -

समाचार पत्र से चियत अंश Newspapers Clippings

Jan 2021 समाचार पत्र से चियत अंश Newspapers Clippings A Daily service to keep DRDO Fraternity abreast with DRDO Technologies, Defence Technologies, Defence Policies, International Relations and Science & Technology खंड : 46 अंक : 17 23-25 जनवरी 2021 Vol. : 46 Issue : 17 23-25 January 2021 रक्षा िवज्ञान पुतकालय Defence Science Library रक्षा वैरक्षाज्ञािनकिवज्ञानसूचना एवपुतकालयं प्रलेखन क द्र Defence ScientificDefence Information Science & Documentation Library Centre - मेरक्षाटकॉफवैज्ञािनकहाउस,स िदलीूचना एवं 110प्रलेखन 054क द्र Defence ScientificMetcalfe Information House, Delhi & ‐ Documentation110 054 Centre मेटकॉफ हाउस, िदली - 110 054 Metcalfe House, Delhi‐ 110 054 CONTENTS S. No. TITLE Page No. DRDO News 1-17 DRDO Technology News 1-17 1. डीआरडीओ ने �कया �माट� एंट� एयरफ��ड वेपन का सफल उड़ान पर��ण 1 2. Successful flight test of Smart Anti Airfield Weapon 2 3. Visit of Vice Chief of the Air Staff to CAW, DRDO Hyderabad and Air Force 2 Academy 4. वाय ु सेना उप�मुख ने सीएड��य,ू डीआरडीओ हैदराबाद और वाय ु सेना अकादमी का दौरा �कया 3 5. India working on 5th-generation fighter planes: IAF Chief 4 6. DRDO successfully tests smart anti-airfield weapon for 9th time 5 7. भारत ने बनाया एक और खतरनाक और �माट� ह�थयार, द�मनु के हवाई रनवे को पलभर म� कर 6 देगा तबाह 8. Air Marshal HS Arora Param visits DRDO Hyderabad, flies Pilatus PC-7 Trainer 7 Aircraft sortie 9. -

Shalyta Magon Army B.Sc, PGDBA(HR) 10 35 54 Sqn Ldr Simran Kaur Bhasin Air Force B.Sc 10 33 56 Maj Anita Marwah Army B.E

Contents About IIMA 2 From the Director's Desk 3 Profile of Faculty Members who taught us 4 From the Course Coordinators 5 What they say about us 6 Batch Profile 8 Placement Preferences 9 Participants Profile Index 10 Resume 12 Course Curriculum 67 Previous Recruiters 68 Placement Coordination 69 1 About IIM-A IIMA has evolved from being India's premier management institute to a notable international school of management in just five decades. It all started with Dr. Vikram Sarabhai and a few spirited industrialists realising that agriculture, education, health, transportation, population control, energy and public administration were vital elements in a growing society, and that it was necessary to efficiently manage these industries. The result was the creation of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad in 1961 as an autonomous body with the active collaboration of the Government of India, Government of Gujarat and the industrial sectors. It was evident that to have a vision was not enough. Effective governance and quality education were seen as critical aspects. From the very start, the founders introduced the concept of faculty governance: all members of the faculty play an important role in administering the diverse academic and non-academic activities of the Institute. The empowerment of the faculty has been the propelling force behind the high quality of learning experience at IIMA. The Institute had initial collaboration with Harvard Business School. This collaboration greatly influenced the Institute's approach to education. Gradually, it emerged as a confluence of the best of Eastern and Western values. 2 From the Director's Desk Dear Recruiter, It gives me immense pleasure and pride to introduce the Tenth batch of Armed Forces Programme (AFP) participants who are undergoing six month residential course in Business Management at IIM Ahmedabad. -

Revamping the Military Training System

Revamping the Military Training System Revamping the Military Training System S.K. Saini* “Victory smiles upon those who anticipate changes in the nature of war.” Giulio Douhet Introduction According to Andrew Marshall, former director of the Office of Net Assessments under the US Secretary of Defence, “a revolution in military affairs (RMA) is a major change in the nature of warfare brought about by the innovative application of new technologies which, combined with dramatic changes in the military doctrine and operational and organisational concepts, fundamentally alters the character and conduct of military operations.” RMA has three main constituents, namely, doctrine, technology and tactics.1 The foremost global trend transforming the security framework is the dramatic growth in information technology (IT) and the RMA it has created.2 India has been acknowledged as a major IT base in the world, with a large work force possessing the necessary skills. It also has reasonably well developed civil programmes in satellite, telecommunications, space and nuclear technology. Besides advanced indigenous technologies being available to the armed forces, a major modernisation programme is underway, wherein state-of-the-art technologies are being acquired *Colonel S.K. Saini is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Defence and Strategic Analyses (IDSA), New Delhi. Journal of Defence Studies • Vol. 2 No. 1 Journal of Defence Studies • Summer 2008 65 S.K. Saini from abroad, especially after the Kargil conflict. Thus technology is not a limiting factor in the Indian context any more. The other two components of RMA – doctrine and tactics – are within the capabilities of the armed forces for making significant changes as determined. -

Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE for AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi

AIR POWER Journal of Air Power and Space Studies Vol. 3, No. 3, Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE FOR AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi AIR POWER is published quarterly by the Centre for Air Power Studies, New Delhi, established under an independent trust titled Forum for National Security Studies registered in 2002 in New Delhi. Board of Trustees Shri M.K. Rasgotra, former Foreign Secretary and former High Commissioner to the UK Chairman Air Chief Marshal O.P. Mehra, former Chief of the Air Staff and former Governor Maharashtra and Rajasthan Smt. H.K. Pannu, IDAS, FA (DS), Ministry of Defence (Finance) Shri K. Subrahmanyam, former Secretary Defence Production and former Director IDSA Dr. Sanjaya Baru, Media Advisor to the Prime Minister (former Chief Editor Financial Express) Captain Ajay Singh, Jet Airways, former Deputy Director Air Defence, Air HQ Air Commodore Jasjit Singh, former Director IDSA Managing Trustee AIR POWER Journal welcomes research articles on defence, military affairs and strategy (especially air power and space issues) of contemporary and historical interest. Articles in the Journal reflect the views and conclusions of the authors and not necessarily the opinions or policy of the Centre or any other institution. Editor-in-Chief Air Commodore Jasjit Singh AVSM VrC VM (Retd) Managing Editor Group Captain D.C. Bakshi VSM (Retd) Publications Advisor Anoop Kamath Distributor KW Publishers Pvt. Ltd. All correspondence may be addressed to Managing Editor AIR POWER P-284, Arjan Path, Subroto Park, New Delhi 110 010 Telephone: (91.11) 25699131-32 Fax: (91.11) 25682533 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.aerospaceindia.org © Centre for Air Power Studies All rights reserved. -

Weekly-Defence-Updates-18.07.2021

WEEKLY DEFENCE UPDATES 18 – 24 JULY 2021 Raksha Mantri Shri Rajnath Singh flags-in Indian Army Skiing Expedition, ARMEX-21, in New Delhi • Army Skiing Expedition is conducted in Himalayan mountain ranges and was flagged off at Karakoram Pass in Ladakh on March 10, 2021, and culminated at Malari in Uttarakhand on July 06, 2021, covering 1,660 kms in 119 days. • During the expedition, the team travelled through several passes of 5,000- 6,500m, glaciers, valleys and rivers. The team also interacted with the local population of the far-flung areas. • The team gathered information about several hitherto unchartered areas along international boundary. • Raksha Mantri commended the courage, dedication and spirit of the Armed Forces. Safety & security of the country is in safe hands, says RM. INS Tabar Arrives at St Petersburg, Russia on Goodwill Visit and to participate in the 325th Russian Navy Day celebrations • Commanded by Captain Mahesh Mangipudi and has a complement of over 300 personnel, this frigate is equipped with a versatile range of weapons and sensors. • During the Russian Navy Day Parade on 25 Jul 21, INS Tabar will join the column of ships that will be reviewed by the President of Russian Federation. DRDO conducts two successful flight tests of Akash-NG • It was tested on July 21, 2021, and then again on July 23, 2021, at ITR Chandipur, Odisha. • This is capable of intercepting high speed & agile aerial threats and is a force multiplier to the defence capabilities of Indian Air Force. About Akash-NG: • It is a new variant of the Akash missile that can strike targets at around 60 km and fly at a speed of up to Mach 2.5. -

Visual Foxpro

Personnel No. Ref. No. Dak Srl.No. Amount Claimed/ Amount Passed/ Memo type/Vr.no Status Name Ref.letter Date Date of receipt Amount disallowed Processing Date Memo No/Dp.no 03606W 409 0000694/2021 7340.00 P VINOD G 22/04/2020 28/04/2020 0 03704T 409 0000693/2021 20615.00 P SUMEET PURI 22/04/2020 28/04/2020 0 03949Z 409/1 0000677/2021 21785.00 P ABHIMANYU S 20/03/2020 28/04/2020 0 04290Z 409/SH 0000683/2021 90265.00 P KISHORE 18/03/2020 28/04/2020 0 04664Z 409/1 0000687/2021 6900.00 P KR BINOY 22/04/2020 28/04/2020 0 04664Z 409/1 0000688/2021 8931.00 P KR BINOY 22/04/2020 28/04/2020 0 04731A 409/3 0000684/2021 6040.00 P HEMANT 21/04/2020 28/04/2020 0 04790K 409/SH 0000680/2021 128533.00 P RAJNEESH 11/03/2020 28/04/2020 0 04834K 409/SH 0000681/2021 89525.00 P MARASANDRA 17/03/2020 28/04/2020 0 04988K 409/1 0000678/2021 2092.00 P ABHILASH 20/03/2020 28/04/2020 0 07513Z 409/3 0000686/2021 43591.00 P PARTH SINGH 22/04/2020 28/04/2020 0 08014N 409 0000692/2021 10890.00 P RAHUL DALAL 22/04/2020 28/04/2020 0 175098A 409/3 0000670/2021 17122.00 P RAM SINGH 22/04/2020 28/04/2020 0 176448W 409/3 0000671/2021 8459.00 P SURENDRA 23/04/2020 28/04/2020 0 177084R 409/3 0000657/2021 16635.00 P MANOJ KUMAR 30/01/2020 28/04/2020 0 177084R 409/3 0000659/2021 62050.00 P MANOJ KUMAR 26/12/2019 28/04/2020 0 179992Z 409/3 0000658/2021 29820.00 P SUNIL KUMAR 05/08/2019 28/04/2020 0 226709Z 409/3 0000673/2021 9414.00 P CHINTHAKAYAL 20/04/2020 28/04/2020 0 227045N 409/3 0000674/2021 9414.00 P RIGZIN ANGDUS20/04/2020 28/04/2020 0 Note : Status 'Y' -> Processing Complete. -

Download in PDF Format

In This Issue Since 1909 PRESIDENT’S ADDRESS TO THE NATION India’s 69th Independence Day 4 (Initially published as FAUJI AKHBAR) Vol. 62 No 16 25 Shravana - 9 Bhadrapada, 1937 (Saka) 16-31 August 2015 The journal of India’s Armed Forces published every fortnight in thirteen languages including Hindi & English on behalf of Ministry of Defence. It is not necessarily an organ for the expression of the Government’s defence policy. The published items represent the views of respective writers and correspondents. Editor-in-Chief Independence Day Motto of ‘Unity and Hasibur Rahman 6 11 Editor Editor (Features) Celebrations... Discipline’ Dr Abrar Rahmani Ehsan Khusro Coordination Business Manager Sekhar Babu Madduri Dharam Pal Goswami Our Correspondents DELHI: Dhananjay Mohanty; Capt DK Sharma; Manoj Tuli; Nampibou Marinmai; Wg Cdr Rochelle D’Silva; Col Rohan Anand; Wg Cdr SS Birdi, Ved Pal; ALLAHABAD: Gp Capt BB Pande; BENGALURU: Dr MS Patil; CHANDIGARH: Parvesh Sharma; CHENNAI: T Shanmugam; GANDHINAGAR: Wg Cdr Abhishek Matiman; GUWAHATI: Lt Col Suneet Newton; IMPHAL: Lt Col Ajay Kumar Sharma; JALANDHAR: Naresh Vijay Vig; JAMMU: Lt Col Manish Mehta; JODHPUR: Lt Col Manish Ojha; KOCHI: Cdr Sridhar E Warrier ; KOHIMA: Lt Col E Musavi; KOLKATA: Gp Capt TK Singha; LUCKNOW: Ms Gargi Malik Sinha; MUMBAI: Cdr Rahul Sinha; Narendra Vispute; NAGPUR: Wg Cdr Samir S Gangakhedkar; PALAM: Gp 18 The Indian Navy and 1965 The Battle of Barki 15 Capt SK Mehta; PUNE: Mahesh Iyengar; SECUNDERABAD: MA Khan Shakeel; 20 Air Force Awardees SHILLONG: Gp Capt Amit Mahajan; SRINAGAR: Col NN Joshi; TEZPUR: Lt Col Sombith Ghosh; THIRUVANANTHAPURAM: Suresh Shreedharan; UDHAMPUR: 22 Role of NCC Cadets in 1965 War Col SD Goswami; VISAKHAPATNAM: Cdr CG Raju. -

Air Navigation in the Service

A History of Navigation in the Royal Air Force RAF Historical Society Seminar at the RAF Museum, Hendon 21 October 1996 (Held jointly with The Royal Institute of Navigation and The Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators) ii The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright ©1997: Royal Air Force Historical Society First Published in the UK in 1997 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available ISBN 0 9519824 7 8 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission from the Publisher in writing. Typeset and printed in Great Britain by Fotodirect Ltd, Brighton Royal Air Force Historical Society iii Contents Page 1 Welcome by RAFHS Chairman, AVM Nigel Baldwin 1 2 Introduction by Seminar Chairman, AM Sir John Curtiss 4 3 The Early Years by Mr David Page 66 4 Between the Wars by Flt Lt Alec Ayliffe 12 5 The Epic Flights by Wg Cdr ‘Jeff’ Jefford 34 6 The Second World War by Sqn Ldr Philip Saxon 52 7 Morning Discussions and Questions 63 8 The Aries Flights by Gp Capt David Broughton 73 9 Developments in the Early 1950s by AVM Jack Furner 92 10 From the ‘60s to the ‘80s by Air Cdre Norman Bonnor 98 11 The Present and the Future by Air Cdre Bill Tyack 107 12 Afternoon Discussions and -

Report of TOC Be Accepted by the Authority, Who Constituted the TOC

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS FOR AMENDMENT TO DPP-2013 INCLUDING FORMULATION OF POLICY FRAMEWORK JULY 2015 (i) (ii) The Committee Chairman Shri Dhirendra Singh Former Secretary to the Govt of India Members Shri Satish B Agnihotri, IAS (Retd.) Air Marshal S Sukumar, (Retd.) Lt Gen AV Subramanian (Retd.) Rear Admiral Pritam Lal (Retd.) Dr. Prahlada, DS & CC & RD (Retd.) Col K V Kuber (Retd.) Shri Sujith Haridas, DDG, CII Shri Sanjay Garg, JS (DIP), MoD Shri Subir Mallick, JS & AM(LS), MoD (iii) (iv) Committee of Experts for Amendment To DPP-2013 Including Formulation of Policy Framework presents its Report to the Government of India Shri Dhirendra Singh Chairman Shri Satish B Agnihotri Air Marshal S Sukumar Lt Gen AV Subramanian IAS (Retd.) (Retd.) (Retd.) Rear Admiral Pritam Lal Dr. Prahlada Col K V Kuber (Retd.) DS & CC & RD (Retd.) (Retd.) Shri Sujith Haridas Shri Sanjay Garg Shri Subir Mallick DDG, CII JS (DIP), MoD JS & AM(LS), MoD 23 July 2015 (v) (vi) Contents Chapter No Subject Page No 1. Defence Materiel 1 2. Defence Industry 13 3. Make In India 37 4. Defence Procurement Procedure 67 5. Trust and Oversight 153 6. Beyond DPP 159 7. Enabling Framework and Summary of Observations & Recommendations 213 8. Appendices 243 9. Acknowledgements 263 (vii) (viii) DEFENCE MATERIEL “Now the main foundation of all States, whether new, old or mixed, are good laws and good arms. But since you cannot have the former without the latter, and where you have the latter, are likely to have the former, I shall here omit all discussion on the subject of laws and speak only of arms........” Machiavelli in ‘The Prince’ 1 DEFENCE MATERIEL 2 DEFENCE MATERIEL CHAPTER 1 DEFENCE MATERIEL 1.1. -

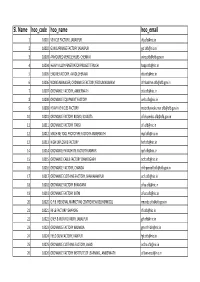

Sl. Name Hoo Code Hoo Name Hoo Email

Sl. Name hoo_code hoo_name hoo_email 1 10001 VEHICLE FACTORY, JABALPUR [email protected] 2 10002 GUN CARRIAGE FACTORY JABALPUR [email protected] 3 10003 ARMOURED VEHICLE HQRS. CHENNAI [email protected] 4 10004 HEAVY ALLOY PENETRATOR PROJECT TIRUCHI [email protected] 5 10005 ENGINE FACTORY, AVADI,CHENNAI [email protected] 6 10006 WORKS MANAGER, ORDNANCE FACTORY,YEDDUMAILARAM [email protected] 7 10007 ORDNANCE FACTORY, AMBERNATH [email protected] 8 10008 ORDNANCE EQUIPMENT FACTORY [email protected] 9 10009 HEAVY VEHICLES FACTORY [email protected] 10 10010 ORDNANCE FACTORY BOARD, KOLKATA [email protected] 11 10011 ORDNANCE FACTORY ITARSI [email protected] 12 10012 MACHINE TOOL PROTOTYPE FACTORY AMBERNATH [email protected] 13 10013 HIGH EXPLOSIVE FACTORY [email protected] 14 10014 ORDNANCE PARACHUTE FACTORY KANPUR [email protected] 15 10015 ORDNANCE CABLE FACTORY CHANDIGARH [email protected] 16 10016 ORDNANCE FACTORY, CHANDA [email protected] 17 10017 ORDNANCE CLOTHING FACTORY, SHAHJAHANPUR [email protected] 18 10018 ORDNANCE FACTORY BHANDARA [email protected] 19 10019 ORDNANCE FACTORY KATNI [email protected] 20 10020 O.F.B. REGIONAL MARKETING CENTRE NEW DELHI(RMCDL) [email protected] 21 10021 RIFLE FACTORY ISHAPORE [email protected] 22 10022 GREY & IRON FOUNDRY, JABALPUR [email protected] 23 10023 ORDNANCE FACTORY NALANDA gm‐ofn‐[email protected] 24 10024 FIELD GUN FACTORY, KANPUR [email protected] 25 10025 ORDNANCE CLOTHING FACTORY, AVADI [email protected] 26 10026 ORDNANCE FACTORY INSTITUTE OF LEARNING , AMBERNATH ofilam‐[email protected] 27 10027 OFB, -

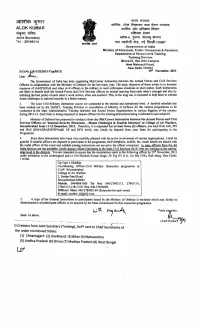

3'116Th" Cg+Ti'i!

3'11 6th" cg+t I'I! m«l~ ~. ~ fllCflI~d o~ ~ ~ ALOK KUMAR CfiTfifCfl 3tR IDflafUJ fcNrrr ~~ IDflafUJ ~ Joint Secretary ~-4,gurn~~ Tel. : 26106314 ~ +15:f1J\ ~. ~ ~'110067 Government of India Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances & Pensions Department of Personnel & Training Training Division Block-IV, Old JNU Campus New Mehrauli Road, New Delhl-110067 D.O.No. ~Oll1S2l2013- Trg(MCI) 19" November, 2013 Dear )I..,v, .The Government of India has been organising Mid-Career Interaction between the Armed Forces and Civil Services Officers in collaboration with the Ministry of Defence for the last many year. The basic objective of these events is to increase exposure of IASIIPSJIFoS and other civil officers to the military to meet unforeseen situations at short notice. Such interactions are likely to benefit both the Armed Forces and Civil Services officers by mutual learning from each other's strength and also by imbibing the best points of each other's work culture, ethos and customs. This, in the long run, is expected to help them to combat future challenges to national security in a better manner. 2. The Joint Civil-Military interaction course are conducted at the tactical and operational level. A detailed schedule has been worked out by the DoP&T, Training Division in consultation of Ministry of Defence for the various programmes to be conducted at the State Administrative Training Institutes and Armed Forces Organisations in various Regions of the country during 2013-14. Each State is being requested to depute officers for the training/interactions being conducted in and around it. 3.