Julie De Brux Editors Theoretical and Empirical Developments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Membres Du Forum Campus France En Juin 2019 372 ÉTABLISSEMENTS

Liste des établissements membres du Forum Campus France en Juin 2019 372 ÉTABLISSEMENTS • UNiversité Toulouse 2 Jean-Jaurés UNIVERSITÉS • Université Paul Sabatier – Toulouse 3 69 • Université François Rabelais – Tours • Université de Technologie de Troyes • Université Polytechnique Hauts-de-France – Valenciennes • Aix-Marseille Université • Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines • Le Mans Université • Sorbonne Université– Paris • Université de Picardie Jules Verne – Amiens • Université d’Angers COMUEs • Université des Antilles – Pointe-à-Pitre 14 • Université d’Artois – Arras • ComUE d’Aquitaine • Université d’Avignon et des Pays du Vaucluse • ComUE Bretagne Loire • Université de Technologie de Belfort – Montbéliard • ComUE Lille Nord de France • Université de Franche-Comté – Besançon • Languedoc Roussillon Universités • Université de Bordeaux • Normandie Université • Université Bordeaux Montaigne • Université confédérale Léonard de Vinci • Université de Bretagne Occidentale – Brest • Université Côte d’Azur • Université de Caen Basse-Normandie • Université Grenoble Alpes • Université de Cergy-Pontoise • Université de Lyon • Université Savoie Mont Blanc – Chambéry • Université Paris-Est • Université de Technologie de Compiègne • Université Paris-Saclay • Université Clermont Auvergne • Université de Recherche Paris Sciences et Lettres • Université de Corse Pascal Paoli – Corte • Université Sorbonne Paris Cité • Université de Bourgogne – Dijon • Université fédérale de Toulouse-Midi-Pyrénées • Université du Littoral-Côte d’Ôpale -

Implantations Des Établissements D'enseignement Supérieur Français Dans Le Monde

IMPLANTATIONS DES ÉTABLISSEMENTS D'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR FRANÇAIS DANS LE MONDE NATURE DE L’IMPLANTATION DISCIPLINES Établissement multi-sites Établissement délocalisé (hors campus multi-sites) Art / Architecture Droit / Économie Sciences et technologies Établissement créé conjointement avec un établissement français Culture (Cuisine, Hôtellerie, Mode, Tourisme) Management Sciences Humaines et Sociales Établissement créé suite à un accord bilatéral : Établissement français partenaire AMÉRIQUE DU NORD EUROPE - CEI Madrid Roumanie Oufa ASIE Asia-Europe Business School + Institut sino-européen ICARE + ParisTech Allemagne ESCP Europe Bucarest IFP School Chine EM Lyon Canada Saint Petersbourg Institut Franco Chinois NEOMA Confucius Institute for Le Cordon bleu Collège juridique franco-roumain Canton Québec Berlin Collège universitaire français d’Ingénierie et de Management Business Université Paris Dauphine + Université Panthéon Sorbonne Efrei@Canton Institut Vatel ESCP Europe + Ponts Paristech Zhuhai Université Toulouse Jean Jaures Suisse Sino-French Institute for Ottawa Nuremberg Royaume-Uni INSEEC Institut franco-chinois de l'éner Institut Vatel Genève Engineering Education and Le Cordon bleu ICN Business School Londres Sino-French Program in Chemi- gie nucléaire + INP Grenoble + Finlande EDHEC INSEEC/CREA Genève Research + Polytech Nantes États-Unis Arménie cal Sciences and Engineering INSTN + Mines Nantes + Chimie Helsinki ESCP Europe Turquie Chengdu + Fédération Gay Lussac Montpellier + Chimie Paris Blaksburg Erevan ESC La Rochelle -

SICAV Digital Funds

SICAV Digital Funds Drescher Webinar April 2021 Chahine Capital - Presentation CHAHINE CAPITAL LAUNCH OF SICAV EUROPEAN PIONEER IN ALPHA PROVIDER ASSETS UNDER MANAGEMENT # EMPLOYEES UCITS FUNDS EX. MANDATES (EUR) DIGITAL FUNDS QUANTITATIVE INVESTMENT SINCE 1998 1.5Bln 17 1998 UCITS EUROPEAN PIONEER IN QUANTITATIVE INVESTMENT STRATEGIES 1998 2004 2017 2019 DIGITAL FUNDS CHAHINE CAPITAL IRIS FINANCE Group CHAHINE CAPITAL Sicav Inception creation becomes principal becomes signatory shareholder of the UN PRI COMPANY 1998 2006 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 DIGITAL STARS DIGITAL STARS DIGITAL STARS DIGITAL STARS DIGITAL STARS LUXFLAG ESG LABEL DIGITAL MARKET EUROPE launch EUROPE EX-UK EUROPE SMALLER US EQUITIES EUROZONE NEUTRAL EUROPE launch COMPANIES launch launch launch launch PRODUCT RANGE 2006 2008 2010 2018 2019 2020 LIPPER AWARD EUROPE LIPPER AWARD EUROPE STANDARD & POOR’S LIPPER AWARD EUROPE LIPPER AWARD EUROPE BEST EUROPEAN EX UK LIPPER AWARD EUROPE BEST EUROPEAN EX UK SICAV OFFSHORE EUROPE BEST EUROPEAN EQUITY BEST EUROPEAN EQUITY EQUITY FUND (3 & 5 BEST EUROPEAN EX UK EQUITY FUND (5 YEARS) AWARD FUND (3 & 5 YEARS) FUND (10 YEARS) YEARS) EQUITY FUND (5 YEARS) 2 Investment Team JULIEN BERNIER o Engineer from École Centrale in Signal Treatment, MBA from IAE Paris o Chahine Capital Lead Portfolio Manager since 2001 CIO o Previously Senior Consultant at JCF in 2000 LEAD PORTFOLIO MANAGER o Civil engineer from ESTP, IAE Paris AYMAR DE LÉOTOING o Chahine Capital Portfolio Manager since 2016 o Previously, Senior Consultant at JCF then FactSet (2000-2007), -

Bachelor Master MBA Ph.D

Among the best programs in Management in France IAE, French University Business Schools Bachelor Master MBA Ph.D IAE, French University Business Schools, are dedicated to research development and graduate education in management. 2 Think and live International Thanks to the quality of the teaching, most IAE, French University Business Schools, have become world-renowned high level education centers. My vision for the IAE, French University Business Schools, is clear, namely to lead business schools in Europe while maintaining our specificity and foothold within the university. Our international strategy is threefold : to be a leader in research in the field of management ; to host a highly reputed faculty, including international scholars from prestigious institutions across the globe ; to increase student mobility and attract the best international students. The internationalization of programs includes courses taught entirely in English and more than 250 international guest teachers. It is also supported by the dynamism of an active network of 1000 first-level partners, some of them AACSB or EQUIS accredited, exchanges of students and teachers in 50 countries. The IAE are part of a French association, named “Réseau IAE” that offers partners the possibility to develop a specific and unique cooperation opportunity with several business schools in France. IAE offers the attend courses from more than 800 programs in French, (undergraduate, graduate and PhD program) or in English. The English offering includes more than 50 undergraduate and graduate programs in Management, Finance, Marketing or Human Resources. Some of these schools or programs benefit from prestigious international accreditation such as EQUIS or EPAS. If you would like to explore the opportunity of collaborating with us, please contact us. -

Georges Hübner, Phd Accounting, Law, Finance and Economics Department Affiliated Professor - Speciality: Finance

Georges Hübner, PhD Accounting, Law, Finance and Economics Department Affiliated Professor - Speciality: Finance Phone : (+32) 42324728 / (+31) 433883817 E-mail : [email protected] / [email protected] Georges Hübner (Ph.D., INSEAD) holds the Deloitte Chair of Portfolio Management and Performance at HEC Management School – University of Liège (HEC-ULg), where he is member of the Board of Directors and chairman of the Master in Management Sciences program. He is also Associate Professor of Finance at Maastricht University, an Affiliate Professor at EDHEC (Lille/Nice) and an Invited Professor at the Solvay Brussels School of Economics and Management. He has taught at the executive and postgraduate levels in several countries in Europe, North America, Africa and Asia. Georges Hübner regularly provides executive training seminars for the preparation of the GARP (Global Association of Risk Professionals) certification. Georges has published numerous research articles about credit risk, hedge funds and derivatives in leading scientific journals including Journal of Business Venturing, Review of Finance, Journal of Banking and Finance, Journal of Empirical Finance, Financial Management and Journal of Portfolio Management. He has written and co-edited several books on hedge funds, operational risk and corporate finance. He is the elected Chairman of the French Finance Association (AFFI) in 2016. Georges Hübner was the recipient of the best paper awards of the Journal of Banking and Finance in 2001 and of “Finance” in 2011, and the co-recipient of the Operational Risk & Compliance Achievement Award 2006, hosted by Operational Risk Magazine, in the best academic paper category. He is also the inventor of the Generalized Treynor Ratio, a simple performance measure for managed portfolios that competes with the traditional performance measures used to assess active portfolio managers. -

Some of the Over 100 Universities Promoted on the Spring ACCESS MBA Tour 2008

Some of the over 100 Universities promoted on the Spring ACCESS MBA Tour 2008 "The individual meetings with Business School Representatives as well as the GMAT advisor and Alba Hult the MBA consultant have been amazingly supportive Aston IAE Paris-Sorbonne and enriching." Audencia IE Javier – Madrid candidate, 2007 AUEB IESE Business School Lausanne INSEAD Cass City International Hellenic Chicago GSB Kellogg- WHU UCD Michael Smurfit CNAM Kenan-Flagler Chappell Hill University of Leicester Columbia Business School Kent University of Sheffield Cranfield Kingston UOWD Duke Leeds University Warwick Fuqua London Business School Wharton "I appreciated having the time to explain the Duke- LSBF WU Wien program and speak individually with candidates.” Goethe Manchester Business School Zayed University Sara Dolan, Esade Business School, Lisbon 2007 E.M. MIP – Pol. Di Milano Lyon OU Business School G 80% of Top 50 Full Time MBA EBS Germany Reims Management School G ENPC Robert Gordon University 75% of Top 50 Executive MBA ESADE Rochester Bern ESCP-EAP Rouen Management School ESSEC RSM Fondazione Campus-Edhec Salford HEC Sciences Po HEC Lausanne SDA – Bocconi HEC Montreal Solvay Business School Hellenic American University Strathclyde Henley Thunderbird Not to be discarded on public property Heriott Watt Tias-Nimbas Advent International All - Rights Reserved 2008 - www.advent.fr Tuck at Dartmouth AccessMBA is a part of Bring this Invitation & Register for free entrance at : www.accessmba.com ONE-TO-ONES INVITINVITATION Across Europe & The Middle -

1St Paris Financial Management Conference (PFMC - 2013)

1st Paris Financial Management Conference (PFMC - 2013) Decembre 16-17 2013, Paris, France Ipag Business School - 184 bd Saint-Germain - 75006 Paris Paris Nice Kunming Los Angeles Welcoming Note It is our great pleasure to cordially welcome you to the inaugural Paris Financial Management Conference (PFMC-2013), which is this year organized by the IPAG Business School in the breathtaking and enchanting “Saint-Germain-des-Prés” district of Paris. This conference draws together an exciting array of academics from research institutions and universities around the world who present papers on nearly every branch of financial management. Over the course of two days the participants will have ample opportunity to present and debate the results of their research and to discuss current academic and practical issues in various financial areas. We are very fortunate in this event to have two invited keynote speakers – Prof. David Chambers (Cambridge Judge Business School, United Kingdom) and Prof. Gilles Hilary (INSEAD, France) – two of the world’s leading researchers in the area of accounting and finance. We would like to express our sincere thanks to them for taking the time out of their busy schedules to participate in and support this event. We would like also to extend our appreciation to all those who submitted, reviewed competitive papers, or who participated in the program as paper presenters, session chairs, discussants, and attendees. Special thanks also go to this year’s Scientific Committee whose contribution is significant to the profile and merit of the conference. Our special thanks go to Brian M. Lucey (Editor of International Review of Financial Analysis) and Marie Brière (Editor of Bankers, Markets & Investors), who have agreed to publish a selection of high quality papers in their journals. -

CFVG HANOI Building 5 & D2, National Economics

CFVG HANOI Building 5 & D2, National Economics University 207 Giai Phong Rd., Tran Dai Nghia St., Tel [84-4] 3 869 10 66 Fax [84-4] 3 869 17 93 CFVG HOCHIMINH CITY University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City 91 Ba Thang Hai St., Dist. 10 Tel [84-8] 3830 01 03 Fax [84-8] 3830 01 14 [email protected] www.cfvg.org EDITORIAL SUPPLY CHAIN AND LOGISTICS IN VIETNAM IS BOOMING. WE GREATLY NEED QUALIFIED PEOPLE WHO HAVE A GLOBAL VISION OF SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT AND LOGISTICS AS WELL AS A GOOD UNDERSTANDING OF ITS VALUE AND IMPACTS ON QUALITY SERVICES AND GOODS MS. NGUYEN THANH NGA HR DIRECTOR, DECATHLON Today, successful companies with European high-ranked rely on the skills of supply chain professors and top industrial management professionals to leaders in Vietnam, which keep their goods and services enable students to obtain a flowing to the marketplace thorough theoretical framework BOLLORE LOGISTICS, HEADQUARTERED IN FRANCE AND quickly, efficiently, and as and practical industrial insights SET UP IN VIETNAM 25 YEARS AGO, IS THE KEY PARTNER OF cost-effective as possible. at the same time. Supply chain management The program is operated is a bright spot among up- MULTINATIONAL AND MEDIUM SIZE COMPANIES WITH IMPORT in Vietnam under a strong Prof. Frédéric Gautier and-coming careers, with SCMM Scientific Director partnership between CFVG / EXPORT ACTIVITIES AND LOCAL LOGISTICS NEEDS. IN A employment opportunities in Business School with a wide variety of industries, in Excellence in Management VERY DYNAMIC VIETNAM MARKET, WE BOLLORE LOGISTICS firms of all sizes. -

Offre De Formation De L'université Psl 2020-2021

OFFRE DE FORMATION DE L’UNIVERSITÉ PSL 2020-2021 Offre de formation de l’Université PSL 1 1 DIPLÔMES AVEC GRADE DE LICENCE Cycle pluridisciplinaire d’études supérieures ............................................................................ 5 Droit ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Économie appliquée ................................................................................................................ 14 Gestion ................................................................................................................................... 14 Sciences sociales .................................................................................................................... 14 Formation du comédien * ......................................................................................................... 41 Informatique des organisations ............................................................................................... 45 Mathématiques appliquées ...................................................................................................... 45 Sciences pour un monde durable ** ......................................................................................... 58 DIPLÔMES AVEC GRADE DE MASTER SCIENCES SOCIALES, ÉCONOMIE, GESTION Master Affaires internationales et développement .................................................................... 64 Master Analyse et politique économiques -

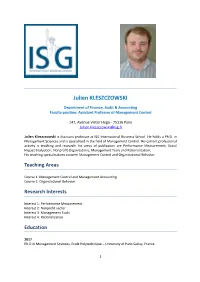

Julien KLESZCZOWSKI

Julien KLESZCZOWSKI Department of Finance, Audit & Accounting Faculty position: Assistant Professor of Management Control 147, Avenue Victor Hugo - 75116 Paris [email protected] Julien Kleszczowski is Assistant professor at ISG International Business School. He holds a Ph.D. in Management Sciences and is specialized in the field of Management Control. His current professional activity is teaching and research: his areas of publication are Performance Measurement, Social Impact Evaluation, Nonprofit Organizations, Management Tools and Rationalization. His teaching specializations concern Management Control and Organizational Behavior. Teaching Areas Course 1: Management Control and Management Accounting Course 2: Organizational Behavior Research Interests Interest 1: Performance Measurement Interest 2: Nonprofit sector Interest 3: Management Tools Interest 4: Rationalization Education 2017 Ph.D in Management Sciences, Ecole Polytechnique – University of Paris Saclay, France. 1 « Construire l’évaluation de l’impact social au sein des organisations non lucratives : instrumentation de gestion et dynamiques de rationalisation ». Supervisor: Nathalie RAULET-CROSET, Professor at IAE Paris (Sorbonne Graduate Business School), Paris Sorbonne University. 2019 Qualification of CNU (French Council of Universities), for the functions of senior Lecturer in Management Sciences (6th section) 2011 Master in solidarity-based economy, Catholic Institute of Paris 2008 Master in management, HEC Paris Teaching Experience Since 2017: Assistant Professor -

Education for Global Citizenship

EDUCATION FOR GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP WWW.INSEEC-U.COM PRESENTATION INSEEC U. is a private multidisciplinary higher education and research institution working in the fields of Management, Engineering, Communication & Design and Political Science, based in Paris, Lyon, Bordeaux, Chambéry-Savoie, London, Geneva, Monaco, San Francisco, Shanghai and Abidjan, which THE INSTITUTION trains 28,000 students and 5,000 executives every year. AT THE HEART OF TRANSITION... A major player in the French educational landscape, INSEEC U. offers a new teaching model adapted to the challenges resulting from ongoing economic, digital, organizational, environmental and societal transition. Building upon research firmly rooted in the realities of today’s world, a capacity for prospective analysis, close ties to business and an international network, INSEEC U. draws on all the talents and all disciplines, allowing its teams, who share its passion for transmitting knowledge, the freedom to undertake projects, design new learning methods and seek out the most promising learning pathways for the future of its students. INSEEC U. deploys innovation to support multiple success stories. 3 LONDON MONACO IN FRANCE PARIS LYON GENEVA SAN FRANCISCO AND IN THE WORLD BORDEAUX SHANGHAI INSEEC U.’s locations in the heart of major cities enable our students to CHAMBÉRY-SAVOIE INSEEC U.’s first campus abroad, the benefit from the economic and cultural drive of the local socio-economic London site in the Marylebone district, context. They also give INSEEC U. the opportunity to contribute to the life INSEEC U. was founded in Bordeaux but paved the way for further international and development of the urban ecosystem and enhance its positioning quickly developed programs in Paris and locations. -

Iae Paris Sorbonne / Almedys

Docteur Karim ZINAI – Président ALMEDYS LIFE MBA Marketing et Communication Santé Executive MBA Healthcare Management and Leadership Lancé en 2014, le MBA Marketing et Communication Santé est un programme académique complet en management de la santé, intensif et professionnalisant, donnant une emphase toute particulière aux disciplines clés de la stratégie, du marketing éthique, de la communication responsable, et de la conduite du changement. Il est issu du partenariat entre l'IAE PARIS SORBONNE et ALMEDYS LIFE. Sa cinquième promotion a intégré le programme en octobre 2019 pour une durée de dix huit mois. Le programme et l’équipe enseignante sont porteurs de l’engagement de vous amener à révéler vos capacités et vos talents de leaders, de managers stratégiques et opérationnels. Un programme Executive Part-time : le MBA Marketing et Communication Santé est ainsi compatible avec un rythme professionnel dense. Un MBA de grade universitaire de Master : l’État a entériné le haut niveau de qualité du diplôme en lui conférant le grade de master dans l’enseignement supérieur. Un équilibre harmonieux entre théorie et pratique professionnelles : l’équipe pédagogique composée d’enseignants-chercheurs et de professionnels de haut niveau insuffle sa passion pour le management en santé, dans toute sa diversité, en privilégiant une approche éthique, responsable et pratique. Les orientations pédagogiques et finalités se déclinent d’une part en stratégies pour anticiper et gérer la complexité en santé, d’autre part en maîtrise opérationnelle des mutations récentes portées notamment par le numérique. En effet, la transformation digitale du monde de la santé et le développement rapide de programmes e-santé au service des patients, des professionnels et du grand public imposent l’appropriation de nouveaux paradigmes.