Quanah Parker and Comanche Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: the Ih Story and the Legend Booth Library

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Booth Library Programs Conferences, Events and Exhibits Spring 2015 Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: The iH story and the Legend Booth Library Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/booth_library_programs Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Booth Library, "Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: The iH story and the Legend" (2015). Booth Library Programs. 15. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/booth_library_programs/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences, Events and Exhibits at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Booth Library Programs by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Quanah & Cynthia Ann Parker: The History and the Legend e story of Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker is one of love and hate, freedom and captivity, joy and sorrow. And it began with a typical colonial family’s quest for a better life. Like many early American settlers, Elder John Parker, a Revolutionary War veteran and Baptist minister, constantly felt the pull to blaze the trail into the West, spreading the word of God along the way. He led his family of 13 children and their descendants to Virginia, Georgia and Tennessee before coming to Illinois, where they were among the rst white settlers of what is now Coles County, arriving in c. 1824. e Parkers were inuential in colonizing the region, building the rst mill, forming churches and organizing government. One of Elder John’s many grandchildren was Cynthia Ann Parker, who was born c. -

Case Studies of the Early Reservation Years 1867-1901

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1983 Diversity of assimilation: Case studies of the early reservation years 1867-1901 Ira E. Lax The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lax, Ira E., "Diversity of assimilation: Case studies of the early reservation years 1867-1901" (1983). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5390. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5390 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s i s t s . Any further r e p r in t in g of it s contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR, Mansfield Library University of Montana Date : __JL 1 8 v «3> THE DIVERSITY OF ASSIMILATION CASE STUDIES OF THE EARLY RESERVATION YEARS, 1867 - 1901 by Ira E. Lax B.A., Oakland University, 1969 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1983 Ap>p|ov&d^ by : f) i (X_x.Aa^ Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate Sdnool Date UMI Number: EP40854 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Papers the Real Wild West Writings

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis papers The Real Wild West Rev. July 2013 Writings 1:1 Typed draft book proposals, overviews and chapter summaries, prologue, introduction, chronologies, all in several versions. Letter from Wallis to Robert Weil (St. Martin’s Press) in reference to Wallis’s reasons for writing the book. 24 Feb 1990. 1:2 Version 1A: “The Making of the West: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen.” 19p. 1:3 Version 1B, 28p. 1:4 Version 1C, 75p. 1:5 Version 2A, 37p. 1:6 Version 2B, 56p. 1:7 Version 2C, marked as final draft, circa 12 Dec 1990. 56p. 1:8 Version 3A: “The Making of the West: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen. The Story of the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch Empire…” 55p. 1:9 Version 3B, 46p. 1:10 Version 4: “The Read Wild West. Saturday’s Heroes: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen.” 37p. 1:11 Version 5: “The Real Wild West: The Story of the 101 Ranch.” 8p. 1:12 Version 6A: “The Real Wild West: The Story of the Miller Brothers and the 101 Ranch.” 25p. 1:13 Version 6B, 4p. 1:14 Version 6C, 26p. 1:15 Typed draft list of sidebars and songs, 2p. Another list of proposed titles of sidebars and songs, 6p. 1:16 Introduction, a different version from the one used in Version 1 draft of text, 5p. 1:17 Version 1: “The Hundred and 101. The True Story of the Men and Women Who Created ‘The Real Wild West.’” Early typed draft text with handwritten revisions and notations. Includes title page, Dedication, Epigraph, with text and accompanying portraits and references. -

Chapter 7 Comanche Historical Ethnography And

Chapter 7 Comanche Historical Ethnography and Ethnohistory ______________________________________________________ 7.1 Introduction The earliest mention of the Comanche in the historical record date to 1706. Comanche ethnogenesis took place about two centuries earlier, after their separation from the Shoshone near the Wind River region. In a step-wise migration bands left the parent society and moved south along the eastern flank of the Rocky Mountains. Initially Comanche bands inhabited the central plains along the Platte, Republican, and Arkansas rivers in eastern Colorado. According to numerous scholars, the Comanche quickly transitioned from a Great Basin culture to a Great Plains life way, although the Comanche retained many Great Basin cultural beliefs and practices.1 However seeking greater trade opportunities and horses, along with the rapidly changing political economic conditions, Comanche bands migrated southeast. By the latter part of the eighteenth century the Comanche consolidated their position on the southern Great Plains after a series of territorial and economic conflicts various tribes and the Spanish.2 Strategically employing warfare, treaty negotiations, and alliances the Comanche controlled the region between the Arkansas and Pecos rivers, an area comprising present-day western Texas and Oklahoma, eastern New Mexico, southeast Colorado, and southwest Kansas.3 By 1820 the Comanche occupied primarily the territory south of the Arkansas River, while the Cheyenne and Arapaho occupied the lands north of the river.4 They controlled this region until the reservation period. The Comanche were never a tribe, unified under a centralized political structure. Rather Comanche ethnicity and social unity was based on common cultural traditions, 600 language, history, and political economic goals. -

Stream Monitoring and Educational Program in the Red River Basin

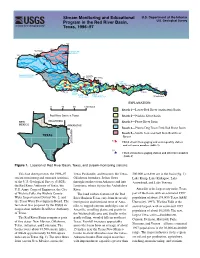

Stream Monitoring and Educational U.S. Department of the Interior Program in the Red River Basin, U.S. Geological Survey Texas, 1996–97 100 o 101 o 5 AMARILLO NORTH FORK 102 o RED RIVER 103 o A S LT 35o F ORK RED R IV ER 1 4 2 PRAIRIE DOG TOWN PEASE 3 99 o WICHITA FORK RED RIVER 7 FALLS CHARLIE 6 RIVE R o o 34 W 8 98 9 I R o LAKE CHIT 21 ED 97 A . TEXOMA o VE o 10 11 R 25 96 RI R 95 16 19 18 20 DENISON 17 28 14 15 23 24 27 29 22 26 30 12,13 LAKE PARIS KEMP LAKE LAKE KICKAPOO ARROWHEAD TEXARKANA EXPLANATION 0 40 80 120 MILES Reach 1—Lower Red River (mainstem) Basin Red River Basin in Texas Reach 2—Wichita River Basin NEW OKLAHOMA Reach 3—Pease River Basin MEXICO ARKANSAS Reach 4—Prairie Dog Town Fork Red River Basin Reach 5—North Fork and Salt Fork Red River TEXAS Basins 12 LOUISIANA USGS streamflow-gaging and water-quality station and reference number (table 1) 22 USGS streamflow-gaging station and reference number (table 1) Figure 1. Location of Red River Basin, Texas, and stream-monitoring stations. This fact sheet presents the 1996–97 Texas Panhandle, and becomes the Texas- 200,000 acre-feet are in the basin (fig. 1): stream monitoring and outreach activities Oklahoma boundary. It then flows Lake Kemp, Lake Kickapoo, Lake of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), through southwestern Arkansas and into Arrowhead, and Lake Texoma. -

American Indians in Texas: Conflict and Survival Phan American Indians in Texas Conflict and Survival

American Indians in Texas: Conflict and Survival Texas: American Indians in AMERICAN INDIANS IN TEXAS Conflict and Survival Phan Sandy Phan AMERICAN INDIANS IN TEXAS Conflict and Survival Sandy Phan Consultant Devia Cearlock K–12 Social Studies Specialist Amarillo Independent School District Table of Contents Publishing Credits Dona Herweck Rice, Editor-in-Chief Lee Aucoin, Creative Director American Indians in Texas ........................................... 4–5 Marcus McArthur, Ph.D., Associate Education Editor Neri Garcia, Senior Designer Stephanie Reid, Photo Editor The First People in Texas ............................................6–11 Rachelle Cracchiolo, M.S.Ed., Publisher Contact with Europeans ...........................................12–15 Image Credits Westward Expansion ................................................16–19 Cover LOC[LC–USZ62–98166] & The Granger Collection; p.1 Library of Congress; pp.2–3, 4, 5 Northwind Picture Archives; p.6 Getty Images; p.7 (top) Thinkstock; p.7 (bottom) Alamy; p.8 Photo Removal and Resistance ...........................................20–23 Researchers Inc.; p.9 (top) National Geographic Stock; p.9 (bottom) The Granger Collection; p.11 (top left) Bob Daemmrich/PhotoEdit Inc.; p.11 (top right) Calhoun County Museum; pp.12–13 The Granger Breaking Up Tribal Land ..........................................24–25 Collection; p.13 (sidebar) Library of Congress; p.14 akg-images/Newscom; p.15 Getty Images; p.16 Bridgeman Art Library; p.17 Library of Congress, (sidebar) Associated Press; p.18 Bridgeman Art Library; American Indians in Texas Today .............................26–29 p.19 The Granger Collection; p.19 (sidebar) Bridgeman Art Library; p.20 Library of Congress; p.21 Getty Images; p.22 Northwind Picture Archives; p.23 LOC [LC-USZ62–98166]; p.23 (sidebar) Nativestock Pictures; Glossary........................................................................ -

Tribal and House District Boundaries

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribal Boundaries and Oklahoma House Boundaries ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 22 ! 18 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 13 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 20 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 7 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Cimarron ! ! ! ! 14 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 11 ! ! Texas ! ! Harper ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! n ! ! Beaver ! ! ! ! Ottawa ! ! ! ! Kay 9 o ! Woods ! ! ! ! Grant t ! 61 ! ! ! ! ! Nowata ! ! ! ! ! 37 ! ! ! g ! ! ! ! 7 ! 2 ! ! ! ! Alfalfa ! n ! ! ! ! ! 10 ! ! 27 i ! ! ! ! ! Craig ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! h ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 26 s ! ! Osage 25 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! a ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 16 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 21 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 58 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 38 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes by House District ! 11 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Absentee Shawnee* ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Woodward ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2 ! 36 ! Apache* ! ! ! 40 ! 17 ! ! ! 5 8 ! ! ! Rogers ! ! ! ! ! Garfield ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 40 ! ! ! ! ! 3 Noble ! ! ! Caddo* ! ! Major ! ! Delaware ! ! ! ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! Mayes ! ! Pawnee ! ! ! 19 ! ! 2 41 ! ! ! ! ! 9 ! 4 ! 74 ! ! ! Cherokee ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ellis ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 41 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 72 ! ! ! ! ! 35 4 8 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 5 3 42 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 77 -

Stormwater Management Program 2013-2018 Appendix A

Appendix A 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) As required under Sections 303(d) and 304(a) of the federal Clean Water Act, this list identifies the water bodies in or bordering Texas for which effluent limitations are not stringent enough to implement water quality standards, and for which the associated pollutants are suitable for measurement by maximum daily load. In addition, the TCEQ also develops a schedule identifying Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) that will be initiated in the next two years for priority impaired waters. Issuance of permits to discharge into 303(d)-listed water bodies is described in the TCEQ regulatory guidance document Procedures to Implement the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (January 2003, RG-194). Impairments are limited to the geographic area described by the Assessment Unit and identified with a six or seven-digit AU_ID. A TMDL for each impaired parameter will be developed to allocate pollutant loads from contributing sources that affect the parameter of concern in each Assessment Unit. The TMDL will be identified and counted using a six or seven-digit AU_ID. Water Quality permits that are issued before a TMDL is approved will not increase pollutant loading that would contribute to the impairment identified for the Assessment Unit. Explanation of Column Headings SegID and Name: The unique identifier (SegID), segment name, and location of the water body. The SegID may be one of two types of numbers. The first type is a classified segment number (4 digits, e.g., 0218), as defined in Appendix A of the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (TSWQS). -

Application and Utility of a Low-Cost Unmanned Aerial System to Manage and Conserve Aquatic Resources in Four Texas Rivers

Application and Utility of a Low-cost Unmanned Aerial System to Manage and Conserve Aquatic Resources in Four Texas Rivers Timothy W. Birdsong, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744 Megan Bean, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 5103 Junction Highway, Mountain Home, TX 78058 Timothy B. Grabowski, U.S. Geological Survey, Texas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Texas Tech University, Agricultural Sciences Building Room 218, MS 2120, Lubbock, TX 79409 Thomas B. Hardy, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Thomas Heard, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Derrick Holdstock, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 3036 FM 3256, Paducah, TX 79248 Kristy Kollaus, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Stephan Magnelia, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, P.O. Box 1685, San Marcos, TX 78745 Kristina Tolman, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Abstract: Low-cost unmanned aerial systems (UAS) have recently gained increasing attention in natural resources management due to their versatility and demonstrated utility in collection of high-resolution, temporally-specific geospatial data. This study applied low-cost UAS to support the geospatial data needs of aquatic resources management projects in four Texas rivers. Specifically, a UAS was used to (1) map invasive salt cedar (multiple species in the genus Tamarix) that have degraded instream habitat conditions in the Pease River, (2) map instream meso-habitats and structural habitat features (e.g., boulders, woody debris) in the South Llano River as a baseline prior to watershed-scale habitat improvements, (3) map enduring pools in the Blanco River during drought conditions to guide smallmouth bass removal efforts, and (4) quantify river use by anglers in the Guadalupe River. -

2) Economy, Business

2) Economy, Business : The majority of tribes' economies rely on Casinos. There are a huge amount of Casinos in Oklahoma, more than in any other state in the USA. But they also rely on the soil resources, there are tribes who are very rich thanks to their oil resources. Natural resources After 1905 deposits of lead and zinc in the Tri-State Mining District made the Quapaws of Ottawa County some of the richest Indians of the USA. Zinc mines also left hazardous waste that still poisons parts of their lands. The Osages became known as the world's richest Indians because their “head right” system distributed the royalties from their “underground reservation” equally to the original allottees. The Osage's territory was full of oil. Gaming revenues The Chickasaw are today the richest tribe in Oklahoma thanks to their Casinos they make a lot of profit. On their website you can read : “From Bank2, Bedre Chocolates, KADA and KYKC radio stations and the McSwain Theatre to the 13 gaming centers, travel plazas and tobacco stores, the variety and prosperity of the Chickasaw Nation's businesses exemplifies the epitome of economic success!”. The Comanche Tribe derives revenue from four casinos. The Comanche Nation Casino in Lawton features a convention center and hotel and has a surface of 45,000 square feet. The others are the Red River Casino at Devol north of the Red River, and two small casinos : Comanche star casino east of Walters and Comanche Spur Casino near Elgin. Enlargements of the casinos are planned . There are smoke shops and convenience stores in the casinos. -

Ed 380 362 Title Institution Pub Date Note Available From

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 380 362 SO 024 456 TITLE North American Indians: Smithsonian Institution Teacher's Resource Guide. INSTITUTION National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC. PUB DATE [93] NOTE 58p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560. PUB TYPE Guidas Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indians; Elementary Secondary Education; Instructional Materials; Library Materials; Museums; *North American Culture; *North American History; *North Americans; Photographs; Social Studies; Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS Smithsonian Institution ABSTRACT This teacher's resource guide produced by the National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian Institution) is a collection of materials about North American Indians covering 3 categories, including an introduction, selected bibliographies, and a listing photographs and portraits. Additionally, there is a collecting of answers to questions that visitors often ask when they explore this Museum's American Indian exhibition galleries. The introduction consists of teaching activities with background information on North American Indian myths and legends; methods to eliminate American Indian stereotypes; and origins of the American Indians. In the selected bibliographies, there are teacher and student bibliographies and teaching kits and other materials; native American resources: books, magazines, and guides for kindergarten through ninth -

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’S Impact on the Western

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’s Impact on the Western Jacob A. Williams A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies University of Washington 2012 Committee: Claudia Gorbman E. Joseph Sharkey Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Dedication ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction 1 Section I The Anti-Hero: Newborn or Reborn Hero? 4 Section II A Greek Tradition: Violence as Catharsis 11 Section III The Theseus Theory 21 Section IV A Modern Greek Tale: The Outlaw Josey Wales 31 Section V The Euripides Effect: Bringing the Audience on Stage 40 Section VI The Importance of the Western Myth 47 Section VII Conclusion: The Immortality of the Western 49 Bibliography 53 Sources Cited 62 i Dedication To my wife and children, whom I cherish every day: To Brandy, for always being the one person I can always count on, and for supporting me through this entire process. You are my love and my life. I couldn’t have done any of this without you. To Andrew, for always being so responsible, being an awesome big brother to your siblings, and always helping me whenever I need you. You are a good son, and I am proud of the man you are becoming. To Tristan, for always being my best friend, and my son. You never cease to amaze and inspire me. Your creativity exceeds my own. To Gracie, for being my happy “Pretty Princess.” Thank you for allowing me to see the world through the eyes of a nature-loving little girl.