This NEWSLETTER Is Edited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negotiating Transboundary River Governance in Myanmar

Number 529 | October 8, 2020 EastWestCenter.org/APB Negotiating Transboundary River Governance in Myanmar By Khin Ohnmar Htwe Myanmar lies in the northwestern part of Indo‐Chinese Peninsular or mainland South‐East Asia. It is bounded by China on the north and north‐east, Laos on the east, Thailand on the south‐east, and Bangladesh and India on the west. There are 7 major drainage areas or catchment areas in Myanmar comprising a series of river‐ valleys running from north to south. The drainage areas in Myanmar are Ayeyarwady and Chindwin Rivers and tributaries (55.05%), Thanlwin (Salween) River and tributaries (18.43%), Siaung River and tributaries (5.38%), Kaladan and Lemyo Rivers and tributaries (3.76%), Yangon River and tributaries (2.96%), Tanintharyi River and tributaries (2.66%), and Minor Coastal Streams (11.76%). Myanmar possesses 12% of Asia’s fresh water resources and 16% of that of the Khin Ohnmar Htwe, ASEAN naons. Growing naonwide demand for fresh water has heightened the challenges of water Director of the Myanmar security. The transboundary river basins along the border line of Myanmar and neighboring countries Environment Instute, are the Mekong, Thanlwin (Salween), Thaungyin (Moai), Naf, and Manipu rivers. The Mekong River is explains that: “Since the also an important transboundary river for Myanmar which it shares with China, Laos, and Thailand. country has both naonal and The Mekong River, with a length of about 2,700 miles (4,350 km), rises in southeastern Qinghai internaonal rivers, Province, China, flows through the eastern part of the Tibet Autonomous Region and Yunnan Province, and forms part of the internaonal border between Myanmar (Burma) and Laos, as well as between Myanmar needs to be Laos and Thailand. -

Floodplain Deposits, Channel Changes and Riverbank Stratigraphy of the Mekong River Area at the 14Th-Century City of Chiang Saen, Northern Thailand

Boise State University ScholarWorks Geosciences Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of Geosciences 10-15-2008 Floodplain Deposits, Channel Changes and Riverbank Stratigraphy of the Mekong River Area at the 14th-Century City of Chiang Saen, Northern Thailand. Spencer H. Wood Boise State University Alan D. Ziegler University of Hawaii Manoa Tharaporn Bundarnsin Chiang Mai University This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. © 2009, Elsevier. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at Geomorphology, doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.04.030 Published article: Wood, S.H., Ziegler, A.D., and Bundarnsin, T., 2008. Floodplain deposits, channel changes and riverbank stratigraphy of the Mekong River area at the 14th-Century city of Chiang Saen, Northern Thailand. Geomorphology, 101, 510-523. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.04.030. Floodplain deposits, channel changes and riverbank stratigraphy of the Mekong River area at the 14th-Century city of Chiang Saen, Northern Thailand. Spencer. H. Wood a,*, Alan D. Zieglerb, Tharaporn Bundarnsinc a Department Geosciences, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho 83725, USA b Geography Department, University of Hawaii Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822 USA c Dept. Geological Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand 50200 *Corresponding author. E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract the active strike-slip Mae Chan fault has formed Riverbank stratigraphy and paleochannel the upstream 2-5-km wide floodplain at Chiang patterns of the Mekong River at Chiang Saen Saen, and downstream has diverted the river into provide a geoarchaeological framework to a broad S-shaped loop in the otherwise straight explore for evidence of Neolithic, Bronze-age, course of the river. -

Northern Thailand

© Lonely Planet Publications 339 Northern Thailand The first true Thai kingdoms arose in northern Thailand, endowing this region with a rich cultural heritage. Whether at the sleepy town of Lamphun or the famed ruins of Sukhothai, the ancient origins of Thai art and culture can still be seen. A distinct Thai culture thrives in northern Thailand. The northerners are very proud of their local customs, considering their ways to be part of Thailand’s ‘original’ tradition. Look for symbols displayed by northern Thais to express cultural solidarity: kàlae (carved wooden ‘X’ motifs) on house gables and the ubiquitous sêua mâw hâwm (indigo-dyed rice-farmer’s shirt). The north is also the home of Thailand’s hill tribes, each with their own unique way of life. The region’s diverse mix of ethnic groups range from Karen and Shan to Akha and Yunnanese. The scenic beauty of the north has been fairly well preserved and has more natural for- est cover than any other region in Thailand. It is threaded with majestic rivers, dotted with waterfalls, and breathtaking mountains frame almost every view. The provinces in this chapter have a plethora of natural, cultural and architectural riches. Enjoy one of the most beautiful Lanna temples in Lampang Province. Explore the impressive trekking opportunities and the quiet Mekong river towns of Chiang Rai Province. The exciting hairpin bends and stunning scenery of Mae Hong Son Province make it a popular choice for trekking, river and motorcycle trips. Home to many Burmese refugees, Mae Sot in Tak Province is a fascinating frontier town. -

Border Myanmar Migrant Worker's Labor Market

PAPER NO. 8 / 2012 Mekong Institute Research Working Paper Series 2012 The Study of Cross – border Myanmar Migrant Worker’s Labor Market: Policy Implications for Labor Management in Chiang Rai City, Chiang Rai Province, Thailand Natthida Jumpa December, 2012 Natthida Jumpa is pursuing a degree in Master of Science in Project Management Program at Chiangrai Rajabhat University. At present she is a researcher and a Chief of the Dean Office, International College of Mekong Region, Chiangrai Rajabhat University. She hopes that after she graduates Master degree she will be part of the academic staff and she will doing research based on regional development for solving the existing problems in GMS countries. This publication of Working Paper Series is part of the Mekong Institute – New Zealand Ambassador Scholarship (MINZAS) program. The project and the papers published under this series are part of a capacity-building program to enhance the research skills of young researchers in the GMS countries. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this report are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Mekong Institute or its donors/sponsors. Mekong Institute does not guarantee the accuracy of the data include in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. For more information, please contact the Technical Coordination and Communication Department of Mekong Institute, Khon Kaen, Thailand. Telephone: +66 43 202411-2 Fax: + 66 43 343131 Email: [email protected] Technical Editors: Dr. Makha Khittasangka, Dean of International College of Mekong Region, Chiangrai Rajabhat University Dr. Suchat Katima, Director, Mekong Institute Language Editor: Ms. -

NORTHERN DELIGHT We Visit a Luxurious Tented Camp in Thailand’S Mystical Golden Triangle

WHO’S GUIDE TO THE MOST LUXURIOUS DESTINATIONS HERE AND ABROAD NORTHERN DELIGHT We visit a luxurious tented camp in Thailand’s mystical Golden Triangle Who l 69 The luxurious private pool at the Explorer’s Lodge. Amy’s tent featured a freestanding Fresh coconuts by the pool with bath and handcrafted furniture. views over the Ruak River. Rustic yet elegant safari-inspired decor features in the breezy superiortents. Enjoy Thai, Laotian and Burmese cooking at Nong Yao restaurant. AMY MILLS WHO Travel Editor Amy takes in the jungle view after her Ruak Bamboo massage. tepping into a traditional long-tail boat We arrive at a jetty and climb a set of narrow After lunch, a vintage Land Rover is on hand to king-sized bed, my dream writing desk and of lanterns and baskets woven with fairy lights. a combination of local herbal oils and natural in Thailand’s Golden Triangle, the stairs where we are each encouraged to hit a transport fellow guests to their tents, while I am handcrafted furniture. We end our evening by releasing khom loy bamboo sticks. uniqueness of my destination, where gong three times for health, wealth and luck. told mine is only a five-minute walk away. The pièce de résistance, though, is the lanterns into the sky and making a wish, Walking back to my tent to pack, I think about northern Thailand, Myanmar and Ebullient camp manager Tobias Emmer There are a total of 15 luxury tents – superior freestanding bathtub in the centre of the room. although, in this moment, I already feel the experiences I’ve had and how this property is Laos intersect, is not lost on me. -

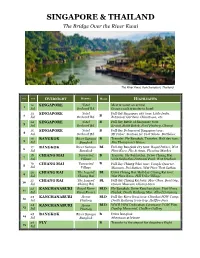

SINGAPORE & THAILAND the Bridge Over the River Kwai

SINGAPORE & THAILAND The Bridge Over the River Kwai The River Kwai, Kanchanaburi, Thailand DAY DATE OVERNIGHT HOTELS MEALS HIGHLIGHTS 12 SINGAPORE Yotel Meet & assist on arrival 1 Jul Orchard Rd. Group coach transfer to hotel 13 SINGAPORE Yotel Full day Singapore city tour: Little India. 2 B Jul Orchard Rd. Botanical Gardens. Chinatown, etc. 14 Yotel B Full day Battle of Singapore tour: 3 SINGAPORE Jul Orchard Rd. Kranji, Bukit Batok, Ford Factory, Changi 15 Yotel B Full day Defences of Singapore tour: 4 SINGAPORE Jul Orchard Rd. Mt Faber. Sentosa Isl. Fort Siloso. Battlebox 16 BANGKOK River Suraya B Transfer. Fly Bangkok. Transfer. Half day tour: 5 Jul Bangkok Jim Thompson’s House 17 River Suraya BL Full day Bangkok city tour: Royal Palace, Wat 6 BANGKOK Jul Bangkok Phra Kaeo, Pho & Arun. Floating Market 18 Tamarind B Transfer. Fly Sukhothai. Drive Chiang Mai 7 CHIANG MAI Jul Village Visit Sukhothai National Park. Wat Srichum 19 Tamarind B 8 CHIANG MAI Full day Chiang Mai tour: Temple Quarter. Jul Village Museum. Doi Suthep, Wat Phra That Suthep 20 The Legend BL Drive Chiang Rai. Half day Chiang Rai tour: 9 CHIANG RAI Jul Chiang Rai Wat Phra Kaeo. Hill Tribe Village 21 The Legend BL Full day Chiang Rai tour: Mae Chan. Boat trip, 10 CHIANG RAI Jul Chiang Rai Opium Museum. Chiang Saen 22 Royal River BLD Fly Bangkok. Drive Kanchanaburi. Visit Nong 11 KANCHANABURI Jul Kwai Resort Pladuk. Death Railway Mus. Allied Cemetery 23 Home BLD Full day River Kwai tour: Chunkai POW Camp, 12 KANCHANABURI Jul Phutoey Death Railway train trip. -

Thailand Year Two (1971-1972) by Peter Crall

Thailand Year Two (1971-1972) by Peter Crall We didn't mind that Chiang Rai lacked the excitement and culture of bigger cities and that it really wasn't much more than a large market town. In those days, the rice fields were still close enough to the center of town that you could encounter an occasional stray water buffalo wandering down the street, minus the little dek [kid] with a stick who should have been tending it. That was OK. It was where we lived. Our first night back in town, we had dinner at the Silana restaurant, one of the nicer places, but still a study in cracked plastic and bad lighting. An epileptic fan on the wall struggled to deliver a breeze. A large framed picture showed King Bhumipon and Walt Disney holding a Mickey Mouse flag. Settling back into our little green house really felt like coming home. It was a place where we were comfortable, surrounded by familiar sights and sounds. But, of course, we were government employees, not tourists, and the rent had to be paid, literally and figuratively, and that meant a return to the classroom and another long cycle of work. As we plunged into our second year of teaching in Chiang Rai, we knew what to expect on the first day of school and were somewhat more relaxed, but that was not to say it was any easier. Learning English was a real challenge for some students, and as their attention wandered and they became frustrated, that caused discipline problems for me. -

Mekong River Commission Basin Development Plan Programme

, Mekong River Commission Basin Development Plan Programme Sida Basin Development Plan 2nd Regional Stakeholder Forum: “Unfolding Perspectives and Options for Sustainable Water Resources Development in the Mekong River Basin” 15 -17 October, 2009, Rimkok Resort and Hotel, Chiang Rai, Thailand As of October 13, 2009 Background The 2nd Regional Stakeholder Forum of the Mekong River Commission Basin Development Plan Programme Phase 2 (BDP2) is an annual forum for riparian countries in the Mekong River Basin (MRB)1, non-state stakeholder groups, development partners, and researchers to discuss challenges and opportunities in water and related resources development and management in the MRB, and provide directions for sustainable basin development. The 1st Regional Stakeholder Consultation entitled “Working with the Mekong River Commission for Sustainable Development of the Mekong River Basin” was held in March 2008 in Vientiane, Lao PDR2. The Consultation hosted more than 120 participants who discussed the mandate and expected role of the MRC in sustainable basin development and the approach that BDP2 would like to follow for the basin development planning in its draft Inception Report. It also facilitated dialogues on how the BDP2 can deliver a relevant planning process in the changing development context of the region, and build ownership of the BDP process and its outputs through genuine stakeholder participation. 1 The Mekong River Basin is shared by China, Myanmar, Lao PDR, Thailand, Cambodia and Viet Nam 2 Please see the proceedings of the Consultation at http://www.mrcmekong.org/programmes/bdp/bdp- publication.htm 1 Central in the BDP process is a basin-wide integrated assessment of the proposed water resources developments in the Lower Mekong Basin (LMB)3 to assess how these developments can be achieved in a sustainable and equitable manner. -

Regional Development of the Golden and Emerald Triangle Areas: Thai Perspective

CHAPTER 6 Regional Development of the Golden and Emerald Triangle Areas: Thai Perspective Nucharee Supatn This chapter should be cited as: Supatn, Nucharee, 2012. “Regional Development of the Golden and Emerald Triangle Areas: Thai Perspective.” In Five Triangle Areas in The Greater Mekong Subregion, edited by Masami Ishida, BRC Research Report No.11, Bangkok Research Center, IDE- JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand. CHAPTER 6 REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE GOLDEN AND EMERALD TRIANGLE AREAS: THAI PERSPECTIVES Nucharee Supatn INTRODUCTION Regarding international cooperation in the Greater Mekong Sub-region, two triangle areas of the three bordering countries also exist in Thailand. The first is known as the “Golden Triangle” of Myanmar, Lao PDR, and Thailand. It was known as the land of opium and the drug trade in a previous era. The second, the “Emerald Triangle,” includes areas of Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Thailand. In addition, there is also the “Quadrangle Area” of China, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Thailand which is an extension of the Golden Triangle. Though there is no border between China and Thailand, there is cooperation in trading, drug and criminal control, and also the development of regional infrastructure, especially in the North-South Economic Corridor (NSEC) and the 4th Thai-Laos Friendship Bridge which is currently under construction. Figure 1 shows the location of the two triangles. The circled area indicates the Golden Triangle, which is located in the upper-north of Thailand, whereas the Emerald Triangle is in the northeastern region of the country. However, as these two triangles are located in different regions of Thailand with different characteristics and contexts, the discussions of each region are presented separately. -

Northern Thailand & Laos

` Northern Thailand & Laos “The very best South East Asia has to offer the adventure motorcyclist” Highlights Include: Luang Prabang | Golden Triangle | Mekong River | White Temple | Tribal Villages Start/Finish Location: Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand Why go to Laos? Imagine a country where your pulse relaxes, smiles are genuine and locals are still curious about you. A place where it’s easy to make a quick detour and find yourself well and truly off the traveller circuit, in a landscape straight out of a daydream: jagged limestone cliffs, brooding jungle and the snaking Mekong River. Welcome to Laos, home to as many as 132 ethnic groups and a history steeped in war, imperialism as mysticism. Paddy fields glimmering in the post monsoon light, Buddhist temples winking through morning mist as monks file past French colonial villas… Motorcycling in South East Asia can only be described as an Adventure of a Lifetime and is a perfect mix of excellent roads, spectacular scenery, culinary delights and most of all very warm and welcoming people. Derek: +353 (0) 87 2538472 email: [email protected] David: +353 (0) 87 2982173 email: [email protected] Web www.overlanders.ie ` Included: • All B&B accommodation in good quality hotels. • Motorcycle rental of Suzuki V-Strom 650 or similar. • All Fuel • Support Vehicle • Licensed Tour Company / Guides / Permits (requirement) • Two motorcycle tour guides (One local and one Overlanders) Excluded: • All Flights • Lunch & Evening Meals • Local attraction entry fees etc. • Anything not listed above. Start/Finish location: Chiang Mai, Thailand. Hotel TBC FAQ: 1. What riding gear: We suggest bringing full summer type/ventilated protective motorcycle riding gear with removal inner/outer waterproof layer. -

Chiangrai.Compressed.Pdf

Cover Chiang Rai Eng nt.indd 1 12/28/10 4:25:11 PM Useful Calls Public Relations Office Tel: 0 5371 1870 Provincial Office Tel: 0 5371 1123 Chiang Rai District Office Tel: 0 5375 2177, 0 5371 1288 Chiang Rai Hospital Tel: 0 5371 1300 Mueang Chiang Rai District Police Station Tel: 0 5371 1444 Highway Police Tel: 1193 Tourist Police Tel: 0 5371 7779, 1155 Immigration Tel: 0 2287 3101-10 Mae Sai Immigration Tel: 0 5373 1008-9 Chiang Saen Immigration Tel: 0 5379 1330 Meteorological Department Tel: 1182 Tourism and Sports Office Tel: 0 5371 6519 Chiang Rai Tourism Association Tel: 0 5360 1299 TAT Tourist Information Centers Tourism Authority of Thailand Head Office 1600 Phetchaburi Road, Makkasan, Ratchathewi, Bangkok 10400 Tel: 0 2250 5500 (automatic 120 lines) Fax: 0 2250 5511 E-mail: [email protected] www.tourismthailand.org Ministry of Tourism and Sports 4 Ratchadamnoen Nok Avenue, Bangkok 10100 8.30 a.m.-4.30 p.m. everyday TAT Chiang Rai 448/16 Singhakhlai Road, Amphoe Mueang Chiang Rai, Chiang Rai 57000 Tel: 0 5371 7433, 0 5374 4674-5 Fax: 0 5371 7434 E-mail: [email protected] Areas of Responsibility: Chiang Rai, Phayao King Mengrai the Great Memorial Cover Chiang Rai Eng nt.indd 2 12/28/10 3:49:27 PM 003-066 Chiang Rai nt.indd 2 12/25/10003-066 2:46:22 Chiang PM Rai nt.indd 67 12/25/10 9:58:54 AM CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 5 ATTRACTIONS 7 Amphoe Mueang Chiang Rai 7 Amphoe Mae Lao 12 Amphoe Mae Chan 13 Amphoe Mae Sai 15 Amphoe Mae Fa Luang 16 Amphoe Chiang Saen 19 Amphoe Chiang Khong 22 Amphoe Wiang Kaen 23 Amphoe Thoeng 23 Amphoe Phan 24 -

Faculty of Agricultural Sciences

FACULTY OF AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES Institute of Agricultural Sciences in the Tropics (Hans-Ruthenberg-Institute) University of Hohenheim Agroecology in the Tropics and Subtropics PD Dr. Anna C. Treydte Conflicts of human land-use and conservation areas: The case of Asian elephants in rubber-dominated landscapes of Southeast Asia Dissertation Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree “Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften” (Dr.sc.agr. / Ph.D. in Agricultural Sciences) to the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences presented by: Franziska Kerstin Harich born in Freiburg, Germany Stuttgart 2017 This thesis was accepted as doctoral dissertation in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree “Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften” (Dr.sc.agr. / Ph.D. in Agricultural Sciences) by the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Hohenheim on May 19, 2017. Date of oral examination: June 12, 2017 Examination committee Supervisor and Reviewer PD Dr. Anna C. Treydte Co-Reviewer Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tommaso Savini Additional Examiner Prof. Dr. Reinhard Böcker Head of Committee Prof. Dr. Andrea Knierim Author’s Declaration I, Franziska Kerstin Harich, hereby affirm that I have written this thesis entitled “Conflicts of human land-use and conservation areas: The case of Asian elephants in rubber- dominated landscapes of Southeast Asia” independently as my original work as part of my dissertation at the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Hohenheim. All authors in the quoted or mentioned publications in this manuscript have been accredited. No piece of work by any person has been included without the author being cited, nor have I enlisted the assistance of commercial promotion agencies.