Department of Defense Roles in Stabilization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formation of the Corps of Engineers

Formation of the U.S. Corps of Engineers Father of the Corps of Engineers At age 16 he was engaged by Lord Fairfax as a surveyor’s helper to survey 1.5 million acres of the Northern Neck of Virginia, which extended into the Shenandoah Valley At 17 he began surveying lots in Alexandria for pay, and became surveyor of Culpepper County later that summer. At age 21 he was given a major’s commission and made Adjutant of Southern Virginia. Six months later he led the first of three English expeditions into the Ohio Valley to initially parlay, then fight the French. Few individuals had a better appreciation of the Allegheny Mountains and the general character of all the lands comprising the American Colonies First Engineer Action Battle of Bunker Hill in Boston in 1775 Washington’s First Chief Engineer In 1775 Putnam entered the Continental Army as a lieutenant colonel. He was involved in the organization of the batteries and fortifications in Boston and New York City in 1776 and 1777, serving as Washington’s first chief Engineer. He went on to greater successes commanding a regiment under General Horatio Gates at the Battle of Saratoga in September 1777. He built new fortifications at West Point in 1778 and in 1779 he served under General Anthony Wayne. He was promoted to brigadier general four years later. Rufus Putnam 1738-1824 Chief Engineer 1777 - 1783 Washington pleaded for more engineers, which began arriving from France in 1776. In late 1777 Congress promoted Louis Duportail to brigadier general and Chief Engineer, a position he held for the duration of the war. -

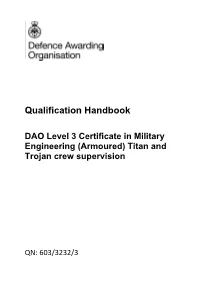

DAO Level 3 Certificate in Military Engineering (Armoured) Titan and Trojan Crew Supervision

Qualification Handbook DAO Level 3 Certificate in Military Engineering (Armoured) Titan and Trojan crew supervision QN: 603/3232/3 The Qualification Overall Objective for the Qualifications This handbook relates to the following qualification: DAO Level 3 Certificate in Military Engineering (Armoured) Titan and Trojan crew supervision Pre-entry Requirements Learners are required to have completed the Class ME (Armd) Class 0-2 course, must be fully qualified AFV crewman and hold full category H driving licence Unit Content and Rules of Combination This qualification is made up of a total of 6 mandatory units and no optional units. To be awarded this qualification the candidate must achieve a total of 13 credits as shown in the table below. Unit Unit of assessment Level GLH TQT Credit number value L/617/0309 Supervise Titan Operation and 3 25 30 3 associated Equipment L/617/0312 Supervise Titan Crew 3 16 19 2 R/617/0313 Supervise Trojan Operation and 3 26 30 3 associated Equipment D/617/0315 Supervise Trojan Crew 3 16 19 2 H/617/0316 Supervise Trojan and Titan AFV 3 10 19 2 maintenance tasks K/617/0317 Carry out emergency procedures and 3 7 11 1 communication for Trojan and Titan AFV Totals 100 128 13 Age Restriction This qualification is available to learners aged 18 years and over. Opportunities for Progression This qualification creates a number of opportunities for progression through career development and promotion. Exemption No exemptions have been identified. 2 Credit Transfer Credits from identical RQF units that have already been achieved by the learner may be transferred. -

18News from the Royal School of Military

RSME MATTERSNEWS FROM THE ROYAL SCHOOL OF MILITARY ENGINEERING GROUP 18 NOVEMBER 2018 Contents 4 5 11 DEMS BOMB DISPOSAL TRAINING UPDATE Defence Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD), It’s the ten-year anniversary of the signing of the Munitions and Search Training Regiment (DEMS RSME Public Private Partnership (PPP) Contract Trg Regt) operates across two sites. The first is and that decade has seen an impressive amount the more established... Read more on page 5 of change. A casual.. Read more on page 11 WELCOME Welcome to issue 18 of RSME Matters. Much has 15 changed across the RSME Group since issue 17 but the overall challenge, of delivering appropriately trained soldiers FEATURE: INNOVATION and military working animals... The Royal School of Military Engineering (RSME) Private Public Partnership (PPP) between the Secretary of State for Defence and... Read more on page 4 Read more on page 15 We’re always looking for new parts of the RSME to explore and share Front cover: Bomb disposal training in action at DEMS Trg Regt – see story on page 9. within RSME Matters. If you’d like us to tell your story then just let us know. Back cover: Royal Engineers approach the Rochester Bridge over the river Medway during a recent night exercise. Nicki Lockhart, Editor, [email protected] Photography: All images except where stated by Ian Clowes | goldy.uk Ian Clowes, Writer and Photographer, 07930 982 661 | [email protected] Design and production: Plain Design | plaindesign.co.uk Printed on FSC® (Forest Stewardship Council) certified paper, which supports the growth of responsible forest management worldwide. -

Diplomacy for the 21St Century: Transformational Diplomacy

Order Code RL34141 Diplomacy for the 21st Century: Transformational Diplomacy August 23, 2007 Kennon H. Nakamura and Susan B. Epstein Foreign Policy Analysts Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Diplomacy for the 21st Century: Transformational Diplomacy Summary Many foreign affairs experts believe that the international system is undergoing a momentous transition affecting its very nature. Some, such as former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, compare the changes in the international system to those of a century ago. Secretary of State Rice relates the changes to the period following the Second World War and the start of the Cold War. At the same time, concerns are being raised about the need for major reform of the institutions and tools of American diplomacy to meet the coming challenges. At issue is how the United States adjusts its diplomacy to address foreign policy demands in the 21st Century. On January 18, 2006, in a speech at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., Secretary Rice outlined her vision for diplomacy changes that she referred to as “transformational diplomacy” to meet this 21st Century world. The new diplomacy elevates democracy-promotion activities inside countries. According to Secretary Rice in her February 14, 2006 testimony before Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the objective of transformational diplomacy is: “to work with our many partners around the world to build and sustain democratic, well-governed states that will respond to the needs of their people and conduct themselves responsibly in the international system.” Secretary Rice’s announcement included moving people and positions from Washington, D.C., and Europe to “strategic” countries; it also created a new position of Director of Foreign Assistance, modified the tools of diplomacy, and changed U.S. -

Fm 3-34.400 (Fm 5-104)

FM 3-34.400 (FM 5-104) GENERAL ENGINEERING December 2008 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online (www.us.army.mil) and General Dennis J. Reimer Training and Doctrine Digital Library at (www.train.army.mil). *FM 3-34.400 (FM 5-104) Field Manual Headquarters No. 3-34.400 (5-104) Department of the Army Washington, DC, 9 December 2008 General Engineering Contents Page PREFACE ............................................................................................................ vii INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... ix PART ONE GENERAL ENGINEERING IN THE OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT Chapter 1 GENERAL ENGINEERING AS AN ENGINEER FUNCTION ............................ 1-1 Full Spectrum General Engineering ................................................................... 1-1 Employment Considerations For General Engineering ...................................... 1-6 Assured Mobility Integration ............................................................................... 1-8 Full Spectrum Operations ................................................................................... 1-9 Homeland Security Implications For General Engineering .............................. 1-12 Chapter 2 OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT ...................................................................... 2-1 Operational Environment ................................................................................... -

Inspection of the Bureau of African Affairs' Foreign Assistance Program

UNCLASSIFIED ISP-I-18-02 Office of Inspections October 2017 Inspection of the Bureau of African Affairs’ Foreign Assistance Program Management BUREAU OF AFRICAN AFFAIRS UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED October 2017 OFFICE OF INSPECTIONS Bureau of African Affairs Inspection of the Bureau of African Affairs’ Foreign Assistance Program Management ISP-I-18-02 What OIG Found What OIG Inspected The Bureau of African Affairs led or participated in at least OIG inspected the Bureau of African Affairs 25 distinct political, security, and economic initiatives on from April 12 to May 12, 2017. the continent, which created a complex planning and program management environment. What OIG Recommended The bureau had not conducted a strategic review of its OIG made 10 recommendations to improve foreign assistance programs to reduce administrative the Bureau of African Affairs’ management of fragmentation and duplication among offices and ensure foreign assistance programs, including that programs were clearly aligned with current policy recommendations to consolidate duplicative priorities. administrative functions, standardize foreign The bureau returned $4.96 million in canceled foreign assistance business processes, and improve assistance funds to the U.S. Department of the Treasury in risk management. FY 2016 despite having statutory authority to extend the period of availability for most foreign assistance In its comments on the draft report, the appropriations. Bureau of African Affairs concurred with all 10 The bureau had not established policy and procedures for recommendations. OIG considers the identifying, assessing, and mitigating terrorist financing recommendations resolved. The bureau’s risks for its programs in countries where terrorist response to each recommendation, and OIG’s organizations, such as Al-Shabaab and Boko Haram, reply, can be found in the Recommendations operate. -

Defence Against Terrorism

Centre of Excellence - Defence Against Terrorism Osman AYTAÇ Col TUR ARMY Chief Education & Training Department [email protected] NATO SPS INFORMATION DAY 4 February 2010 İstanbul / TURKEY UNCLASSIFIED 1/25 Agenda * Centre of Excellence Defence Against Terrorism * COEDAT Activities Supported by SPS Programme UNCLASSIFIED 2/25 Prague Summit * Transformation of NATO should continue, * Capabilities against the contemporary threats must be addressed: − Defence against terrorism, − Strengthen capabilities to defend against cyber attacks, − Augment and improve CBRN defence capabilities, − Examine options for addressing the increasing missile threat . UNCLASSIFIED 3/25 Centres of Excellence New NATO command arrangements should be supported by a network of Centres of Excellence (COEs) UNCLASSIFIED 4/25 Milestones Centre of Excellence Defence Against Terrorism Declaration of Intention : 01 December 2003 Inauguration of the Centre : 28 June 2005 New Allies Join the Centre : Fall 2005-Fall 2006 NATO Accreditation : 14 August 2006 UNCLASSIFIED 5/25 Centre of Excellence (COE) COE is a nationally or multinationally sponsored entity which offers recognized expertise & experience to the benefit of the alliance especially in support of transformation process*. * Reference: MCM-236-03 MC Concept for Centers of Excellence, 04 December ‘03 UNCLASSIFIED 6/25 Centres of Excellence in NATO * Joint Air Power Competence (DEU) * Defence Against Terrorism (TUR) * Naval Mine Warfare (BEL) * Combined Joint Ops. from the Sea (USA) * Cold Weather Ops. (NOR) -

Background and Congressional Action on the Civilian Response/Reserve Corps and Other Civilian Stabilization and Reconstruction Capabilities

Peacekeeping/Stabilization and Conflict Transitions: Background and Congressional Action on the Civilian Response/Reserve Corps and other Civilian Stabilization and Reconstruction Capabilities Nina M. Serafino Specialist in International Security Affairs July 23, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32862 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Peacekeeping/Stabilization and Conflict Transitions Summary The 111th Congress will face a number of issues regarding the development of civilian capabilities to carry out stabilization and reconstruction activities. In September 2008, Congress passed the Reconstruction and Stabilization Civilian Management Act, 2008, as Title XVI of the Duncan Hunter National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2009 (S. 3001, P.L. 110-417, signed into law October 14, 2008). This legislation codified the existence and functions of the State Department Office of the Coordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization (S/CRS) and authorized new operational capabilities within the State Department, a Civilian Response Corps of government employees with an active and a standby component, and a Civilian Reserve Corps. S/CRS was established in 2004 to address longstanding concerns, both within Congress and the broader foreign policy community, over the perceived lack of the appropriate capabilities and processes to deal with transitions from conflict to stability. These capabilities and procedures include adequate planning mechanisms for stabilization and reconstruction operations, efficient interagency coordination structures and procedures in carrying out such tasks, and appropriate civilian personnel for many of the non-military tasks required. Effectively distributing resources among the various executive branch actors, maintaining clear lines of authority and jurisdiction, and balancing short- and long-term objectives are major challenges for designing, planning, and conducting post-conflict operations, as is fielding the appropriate civilian personnel. -

Military Engineering 5-6 Syllabus

Fairfax Collegiate 703 481-3080 · www.FairfaxCollegiate.com Military Engineering 5-6 Syllabus Course Goals 1 Physics Concepts and Applications Students learn the basics of physics, including Newton’s laws and projectile motion. They will apply this knowledge through the construction of miniature catapult structures and subsequent analysis of their functions. 2 History of Engineering Design Students learn about the progression of military and ballistics technology starting in the ancient era up until the end of the Middle Ages. Students will identify the context that these engineering breakthroughs arose from, and recognize the evolution of this technology as part of the engineering design process. 3 Design, Fabrication, and Testing Students work in small teams to build and test their projects, including identifying issues and troubleshooting as they arise. Students will demonstrate their understanding of this process through the design, prototyping, testing, and execution of an original catapult design. Course Topics 1 Ancient Era Siege Weapons 1.1 Brief History of Siege Warfare 1.2 Basic Physics 2 The Birth of Siege Warfare 2.1 Ancient Greece 2.2 Projectile Motion 3 Viking Siege! 3.1 History of the Vikings 3.2 Building with Triangles 4 Alexander the Great and Torsion Catapults Fairfax Collegiate · Have Fun and Learn! · For Rising Grades 3 to 12 4.1 The Conquests of Alexander the Great 4.2 The Torsion Spring and Lithobolos 5 The Romans 6 Julius Caesar 7 The Crusades 8 The Middle Ages 9 Castle Siege Course Schedule Day 1 Introduction and Ice Breaker Students learn about the course, their instructor, and each other. -

Drawing on the Full Strength of America

A POWERFUL VOICE FOR LIFESAVING ACTION DRAWING ON THE FULL STRENGTH OF AMERICA SEEKING GREATER CIVILIAN CAPACITY IN U.S. FOREIGN AffAIRS SEPTEMBER 2009 RON CAPPS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank the many people both inside and outside of government who graciously shared their personal and professional insights for this paper. Sadly, having promised them anonymity in return for candor I cannot single out those who were particularly helpful. I also thank my colleagues at Refugees International for their support and confidence. Finally, Refugees International recognizes the generous financial support of the Connect US Fund for making this research possible. U.S. service members ABOUT REFUGEES INTERNATIONAL construct a school in Wanrarou, Benin, June Refugees International advocates for lifesaving assistance and protection for displaced people 14, 2009. The school and promotes solutions to displacement crises. Based on our on-the-ground knowledge of project was being key humanitarian emergencies, Refugees International successfully pressures governments, conducted as part of a international agencies and nongovernmental organizations to improve conditions for combined U.S.-Beninese military training exercise displaced people. with humanitarian projects scheduled to run Refugees International is an independent, non-profit humanitarian advocacy organization concurrently. based in Washington, DC. We do not accept government or United Nations funding, relying instead on contributions from individuals, foundations and corporations. Learn more at Credit: U.S. Marine www.refugeesinternational.org. Corps/Master Sgt. Michael Q. Retana sePtemBer 2009 DRAWING ON THE FULL STRENGTH OF AMERICA: SeeKing Greater CIVilian CAPacitY in U.S. Foreign Affairs TaBLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary. i Introduction. 1 Part I: “The Eclipse of the State Department”. -

Peacekeeping/Stabilization and Conflict Transitions

Peacekeeping/Stabilization and Conflict Transitions: Background and Congressional Action on the Civilian Response/Reserve Corps and other Civilian Stabilization and Reconstruction Capabilities Nina M. Serafino Specialist in International Security Affairs October 2, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32862 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Peacekeeping/Stabilization and Conflict Transitions Summary In November 2011, the Obama Administration announced the creation of a new State Department Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO) to provide the institutional focus for policy and “operational solutions” to prevent, respond to, and stabilize crises in priority states. This bureau integrates the former Office of the Coordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization (S/CRS). In December 2011, the Administration nominated Frederick D. Barton to two posts: the Assistant Secretary for Conflict and Stabilization Operations and the Coordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization. The second session of the 112th Congress may wish to follow the progress of the CSO Bureau in furthering the work of S/CRS as part of appropriations and oversight functions. Congress established S/CRS by law in the Reconstruction and Stabilization Civilian Management Act, 2008, as Title XVI of the Duncan Hunter National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2009 (S. 3001, P.L. 110-417, signed into law October 14, 2008). This legislation codified the existence and functions of S/CRS and authorized new operational capabilities within the State Department, a Civilian Response Corps (CRC) of government employees with an active and a standby component, and a reserve component. Earlier, in 2004, the George W. Bush Administration had stood up S/CRS to address long-standing concerns, both within Congress and the broader foreign policy community, over the perceived lack of the appropriate capabilities and processes to deal with transitions from conflict to stability. -

Military Aspects of Hydrogeology: an Introduction and Overview

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Military aspects of hydrogeology: an introduction and overview JOHN D. MATHER* & EDWARD P. F. ROSE Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: The military aspects of hydrogeology can be categorized into five main fields: the use of groundwater to provide a water supply for combatants and to sustain the infrastructure and defence establishments supporting them; the influence of near-surface water as a hazard affecting mobility, tunnelling and the placing and detection of mines; contamination arising from the testing, use and disposal of munitions and hazardous chemicals; training, research and technology transfer; and groundwater use as a potential source of conflict. In both World Wars, US and German forces were able to deploy trained hydrogeologists to address such problems, but the prevailing attitude to applied geology in Britain led to the use of only a few, talented individuals, who gained relevant experience as their military service progressed. Prior to World War II, existing techniques were generally adapted for military use. Significant advances were made in some fields, notably in the use of Norton tube wells (widely known as Abyssinian wells after their successful use in the Abyssinian War of 1867/1868) and in the development of groundwater prospect maps. Since 1945, the need for advice in specific military sectors, including vehicle mobility, explosive threat detection and hydrological forecasting, has resulted in the growth of a group of individuals who can rightly regard themselves as military hydrogeologists.