JAPANESE COSTUME Author(S): Helen C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Set of Japanese Word Cohorts Rated for Relative Familiarity

A SET OF JAPANESE WORD COHORTS RATED FOR RELATIVE FAMILIARITY Takashi Otake and Anne Cutler Dokkyo University and Max-Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT are asked to guess about the identity of a speech signal which is in some way difficult to perceive; in gating the input is fragmentary, A database is presented of relative familiarity ratings for 24 sets of but other methods involve presentation of filtered or noise-masked Japanese words, each set comprising words overlapping in the or faint signals. In most such studies there is a strong familiarity initial portions. These ratings are useful for the generation of effect: listeners guess words which are familiar to them rather than material sets for research in the recognition of spoken words. words which are unfamiliar. The above list suggests that the same was true in this study. However, in order to establish that this was 1. INTRODUCTION so, it was necessary to compare the relative familiarity of the guessed words and the actually presented words. Unfortunately Spoken-language recognition proceeds in time - the beginnings of we found no existing database available for such a comparison. words arrive before the ends. Research on spoken-language recognition thus often makes use of words which begin similarly It was therefore necessary to collect familiarity ratings for the and diverge at a later point. For instance, Marslen-Wilson and words in question. Studies of subjective familiarity rating 1) 2) Zwitserlood and Zwitserlood examined the associates activated (Gernsbacher8), Kreuz9)) have shown very high inter-rater by the presentation of fragments which could be the beginning of reliability and a better correlation with experimental results in more than one word - in Zwitserlood's experiment, for example, language processing than is found for frequency counts based on the fragment kapit- which could begin the Dutch words kapitein written text. -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

Japanese Costume

-s-t JAPANESE COSTUME BY HELEN C. GUNSAULUS Assistant Curator of Japanese Ethnology WQStTY OF IUR0IS L . MCI 5 1923 FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CHICAGO 1923 >7£ VtT3f 7^ Field Museum of Natural History DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Chicago. 1923 Leaflet Number 12 Japanese Costume Though European influence is strongly marked in many of the costumes seen today in the larger sea- coast cities of Japan, there is fortunately little change to be noted in the dress of the people of the interior, even the old court costumes are worn at a few formal functions and ceremonies in the palace. From the careful scrutinizing of certain prints, particularly those known as surimono, a good idea may be gained of the appearance of all classes of people prior to the in- troduction of foreign civilization. A special selection of these prints (Series II), chosen with this idea in mind, may be viewed each year in Field Museum in Gunsaulus Hall (Room 30, Second Floor) from April 1st to July 1st at which time it is succeeded by another selection. Since surimono were cards of greeting exchanged by the more highly educated classes of Japan, many times the figures portrayed are those known through the history and literature of the country, and as such they show forth the costumes worn by historical char- acters whose lives date back several centuries. Scenes from daily life during the years between 1760 and 1860, that period just preceding the opening up of the coun- try when surimono had their vogue, also decorate these cards and thus depict the garments worn by the great middle class and the military (samurai) class, the ma- jority of whose descendents still cling to the national costume. -

Shigisan Engi Shigisan Engi Overview

Shigisan engi Shigisan engi Overview I. The Shigisan engi or Legends of the Temple on Mount Shigi consists of three handscrolls. Scroll 1 is commonly called “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 2 “The Exorcism of the Engi Emperor,” and Scroll 3 “The Story of the Nun.” These scrolls are a pictorial presentation of three legends handed down among the common people. These legends appear under the title “Shinano no kuni no hijiri no koto” (The Sage of Shinano Province) in both the Uji sh¯ui monogatari (Tales from Uji) and the Umezawa version of the Kohon setsuwash¯u (Collection of Ancient Legends). Since these two versions of the legends are quite similar, one is assumed to be based on the other. The Kohon setsuwash¯u ver- sion is written largely in kana, the phonetic script, with few Chinese characters and is very close to the text of the Shigisan engi handscrolls. Thus, it seems likely that there is a deep connection between the Shigisan engi and the Kohon setsuwash¯u; one was probably the basis for the other. “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 1 of the Shigisan engi, lacks the textual portion, which has probably been lost. As that suggests, the Shigisan engi have not come down to us in their original form. The Shigisan Ch¯ogosonshiji Temple owns the Shigisan engi, and the lid of the box in which the scrolls were stored lists two other documents, the Taishigun no maki (Army of Prince Sh¯otoku-taishi) and notes to that scroll, in addition to the titles of the three scrolls. -

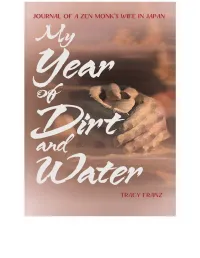

My Year of Dirt and Water

“In a year apart from everyone she loves, Tracy Franz reconciles her feelings of loneliness and displacement into acceptance and trust. Keenly observed and lyrically told, her journal takes us deep into the spirit of Zen, where every place you stand is the monastery.” KAREN MAEZEN MILLER, author of Paradise in Plain Sight: Lessons from a Zen Garden “Crisp, glittering, deep, and probing.” DAI-EN BENNAGE, translator of Zen Seeds “Tracy Franz’s My Year of Dirt and Water is both bold and quietly elegant in form and insight, and spacious enough for many striking paradoxes: the intimacy that arises in the midst of loneliness, finding belonging in exile, discovering real freedom on a journey punctuated by encounters with dark and cruel men, and moving forward into the unknown to finally excavate secrets of the past. It is a long poem, a string of koans and startling encounters, a clear dream of transmissions beyond words. And it is a remarkable love story that moved me to tears.” BONNIE NADZAM, author of Lamb and Lions, co-author of Love in the Anthropocene “A remarkable account of a woman’s sojourn, largely in Japan, while her husband undergoes a year-long training session in a Zen Buddhist monastery. Difficult, disciplined, and interesting as the husband’s training toward becoming a monk may be, it is the author’s tale that has our attention here.” JOHN KEEBLE, author of seven books, including The Shadows of Owls “Franz matches restraint with reflexiveness, crafting a narrative equally filled with the luminous particular and the telling omission. -

Ore Giapponesi: Giorgio Bernari E Adriano Somigli Lia Beretta

COLLANA DI STUDI GIAPPONESI RICErcHE 4 Direttore Matilde Mastrangelo Sapienza Università di Roma Comitato scientifico Giorgio Amitrano Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale” Gianluca Coci Università di Torino Silvana De Maio Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale” Chiara Ghidini Fondazione Bruno Kessler Andrea Maurizi Università degli Studi di Milano–Bicocca Maria Teresa Orsi Sapienza Università di Roma Ikuko Sagiyama Università degli Studi di Firenze Virginia Sica Università degli Studi di Milano Comitato di redazione Chiara Ghidini Fondazione Bruno Kessler Luca Milasi Sapienza Università di Roma Stefano Romagnoli Sapienza Università di Rom COLLANA DI STUDI GIAPPONESI RICErcHE La Collana di Studi Giapponesi raccoglie manuali, opere di saggistica e traduzioni con cui diffondere lo studio e la rifles- sione su diversi aspetti della cultura giapponese di ogni epoca. La Collana si articola in quattro Sezioni (Ricerche, Migaku, Il Ponte, Il Canto). I testi presentati all’interno della Collana sono sottoposti a una procedura anonima di referaggio. La Sezione Ricerche raccoglie opere collettanee e monografie di studiosi italiani e stranieri specialisti di ambiti disciplinari che coprono la realtà culturale del Giappone antico, moder- no e contemporaneo. Il rigore scientifico e la fruibilità delle ricerche raccolte nella Sezione rendono i volumi presentati adatti sia per gli specialisti del settore che per un pubblico di lettori più ampio. Variazioni su temi di Fosco Maraini a cura di Andrea Maurizi Bonaventura Ruperti Copyright © MMXIV Aracne editrice int.le S.r.l. www.aracneeditrice.it [email protected] via Quarto Negroni, 15 00040 Ariccia (RM) (06) 93781065 isbn 978-88-548-8008-5 I diritti di traduzione, di memorizzazione elettronica, di riproduzione e di adattamento anche parziale, con qualsiasi mezzo, sono riservati per tutti i Paesi. -

Il Mondo Femminile Nell'arte Giapponese

oggetti per passione il mondo femminile nell’arte giapponese A cura di Anna Maria Montaldo e Loretta Paderni copertina e pagine illustrate Le immagini sono tratte da: Suzuki Harunobu, Ehon seirō bijin awase, “Libro illustrato a paragone delle bellezze delle case verdi”, 1770 Oggetti per passione Scenografia Un sentito ringraziamento Il mondo femminile Sabrina Cuccu per la realizzazione della mostra nell’arte giapponese Progetto e del catalogo alla Soprintendenza Indice Fondazione Teatro Lirico di Cagliari al Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini Cagliari, Palazzo di Città Realizzazione Il museo come luogo di scambio e relazione culturale 7 Museo d’Arte Siamese Francesco di Gennaro 27 giugno – 8 settembre 2013 Progetto grafico Soprintendente L’oriente ad ovest della penisola 9 Subtitle Egidio Cossa Progetto e cura della mostra Responsabile della sezione L’arte giapponese nelle collezioni 11 Anna Maria Montaldo, Loretta Paderni Fotografie Eventi e Mostre di Stefano Cardu e Vincenzo Ragusa Fabio Naccari Grazia Poli I collezionisti 12 Realizzazione della mostra Foto oggetti Sezione Eventi e Mostre L’oriente, la ricerca e la passione 14 Musei Civici Cagliari in collaborazione Chise Saito, Art Research Centre, Mario Mineo Il Museo Civico d’Arte Siamese Stefano Cardu 16 con la Soprintendenza al Museo Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Responsabile del Laboratorio L’arte giapponese nella collezione Stefano Cardu 19 Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico Foto libro Harunobu Fotografico e dell’Archivio Fotografico Luigi Pigorini, Roma Quando fuori “c’era tanto mondo...” 22 © Soprintendenza al Museo Nazionale e Storico Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini Testi su concessione del Ministero per i Si ringraziano inoltre Anna Maria Montaldo, Loretta Paderni Beni e le Attività Culturali Ikuko Kaji e Maria Cristina Gasperini Presentarsi in pubblico 25 Giuseppe Ungari (foto pag. -

Japanese Costume

JAPANESE COSTUME BY HELEN C. GUNSAULUS Assistant Curator of Japanese Ethnology FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CHICAGO 1923 Field Museum of Natural History DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Chicago, 1923 Leaflet Number 12 Japanese Costume Though European influence is strongly marked in many of the costumes seen today in the larger sea- coast cities of Japan, there is fortunately little change to be noted in the dress of the people of the interior, even the old court costumes are worn at a few formal functions and ceremonies in the palace. From the careful scrutinizing of certain prints, particularly those known as surimono, a good idea may be gained of the appearance of all classes of people prior to the in- troduction of foreign civilization. A special selection of these prints (Series II), chosen with this idea in mind, may be viewed each year in Field Museum in Gunsaulus Hall (Room 30, Second Floor) from April 1st to July 1st at which time it is succeeded by another selection. Since surimono were cards of greeting exchanged by the more highly educated classes of Japan, many times the figures portrayed are those known through the history and literature of the country, and as such they show forth the costumes worn by historical char- acters whose lives date back several centuries. Scenes from daily life during the years between 1760 and 1860, that period just preceding the opening up of the coun- try when surimono had their vogue, also decorate these cards and thus depict the garments worn by the great middle class and the military ( samurai ) class, the ma- jority of whose descendents still cling to the national costume. -

Types of Japanese Folktales

Types of Japanese Folktales By K e ig o Se k i CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................ 2 Bibliography ................................... ................................ 8 I. Origin of Animals. No. 1-30 .....................................15 II. A nim al Tales. No. 31-74............................................... 24 III. Man and A n im a l............................................................ 45 A. Escape from Ogre. No. 75-88 ....................... 43 B. Stupid Animals. No. 87-118 ........................... 4& C. Grateful Animals. No. 119-132 ..................... 63 IV. Supernatural Wifes and Husbands ............................. 69 A. Supernatural Husbands. No. 133-140 .............. 69 B. Supernatural Wifes. No. 141-150 .................. 74 V. Supernatural Birth. No. 151-165 ............................. 80 VI. Man and Waterspirit. No. 166-170 ......................... 87 VII. Magic Objects. No. 171-182 ......................................... 90 V III. Tales of Fate. No. 183-188 ............................... :.… 95 IX. Human Marriage. No. 189-200 ................................. 100 X. Acquisition of Riches. No. 201-209 ........................ 105 X I. Conflicts ............................................................................I l l A. Parent and Child. No. 210-223 ..................... I l l B. Brothers (or Sisters). No. 224-233 ..............11? C. Neighbors. No. 234-253 .....................................123 X II. The Clever Man. No. 254-262 -

The Costume of Yamabushi "To Put on the Clothing of Yamabushi, Is to Put on the Personality of the Fudo Buddha" Something Always Practiced by the Shugenjas

Doctrines Costumes and Tools symbolisme | www.shugendo.fr Page 4 of 12 7. Not to break good manners and to accept insults from the Elders. 8. On level ground, not to have futile conversations (concerning Dharma or women) 9. Not to touch on the frivolous subjects, not to amuse with laughing at useless words or grievances. 10. When in bed, to fall asleep while using the nenju and reciting mantra) 11. Respect and obey the Veterans, Directors and Masters of Discipline, and read sutras aloud (the yamabushi in mountain have as a practice to speak with full lungs and the texts must be understandable) 12. Respect the regulations of the Directors and the Veterans. 13. Not to allow useless discussions. If the discussion exceeds the limits for which it is intended, one cannot allow it. 14. On level ground not to fall asleep while largely yawning (In all Japan the yawn is very badly perceived; a popular belief even says that the heart could flee the body by the yawn). 15. Those which put without care their sandals of straw (Yatsume-waraji, sandals with 8 eyelets) or which leave them in disorder will be punished with exceptional drudgeries. (It is necessary to have to go with sandals to include/understand the importance which they can have for a shugenja, even if during modern time, the "chika tabi" in white fabric replaced the sandals of straw at many shugenja. Kûban inside Kannen cave on Nevertheless certain Masters as Dai Ajari Miyagi Tainen continue to carry them for their comfort and Tomogashima island during 21 days the adherence which they offer on the wet stones. -

Nolife Y a Pas Que La Vraie Vie Dans La Vie !

Nolife Y a pas que la vraie vie dans la vie ! PDF générés en utilisant les outils open source mwlib. Voir http://code.pediapress.com/ pour plus d’informations. PDF generated at: Sun, 09 May 2010 10:48:58 UTC Contenu Articles Nolife 1 Nolife (télévision) 1 Jpop 10 Musique japonaise 13 Culture japonaise 20 Le Staff 24 Sébastien Ruchet 24 Alex Pilot 24 Thomas Guitard 26 Anciens membres et autres 27 Davy Mourier 27 Monsieur Poulpe 30 Didier Richard 32 Ruddy Pomarede 33 Series et Emissions sur Nolife 34 France Five 34 Flander's Company 37 Nerdz 45 Noob (série télévisée) 51 Karekano 57 Chez Marcus 62 101% 65 Les "cas" Nolife et Cie. 66 Nolife 66 Otaku 70 Geek 72 Nerd 78 Hardcore gamer 81 Hikikomori 82 Références Sources et contributeurs de l'article 86 Source des images, licences et contributeurs 88 Licence des articles Licence 89 1 Nolife Nolife (télévision) Création 1er juin 2007 à 21h00 Slogan Y’a pas que la vraie vie dans la vie ! Langue Français Pays d'origine France Statut Thématique nationale privée Siège social Paris [1] Site Web www.nolife-tv.com Diffusion Analogique Non Numérique Non Satellite Non Câble Non ADSL Freebox TV : chaîne n° 123 Alice : chaîne n° 76 Neuf Box TV : chaîne n° 61 Orange TV : chaîne n° 111 Bbox TV: chaîne n° 128 Tele 2 : chaîne n° 61 Nolife est une chaîne de télévision thématique française axée sur les cultures geek et japonaise. Historique La chaîne a fait sa première apparition le 12 février 2007 avec la mise en ligne d'un site web annonçant une future chaîne pour les geeks et otakus, son lancement était annoncé pour fin mars 2007. -

Japanese Folk Tale

The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale Copublished with Asian Folklore Studies YANAGITA KUNIO (1875 -1962) The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale Translated and Edited by FANNY HAGIN MAYER INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington This volume is a translation of Nihon mukashibanashi meii, compiled under the supervision of Yanagita Kunio and edited by Nihon Hoso Kyokai. Tokyo: Nihon Hoso Shuppan Kyokai, 1948. This book has been produced from camera-ready copy provided by ASIAN FOLKLORE STUDIES, Nanzan University, Nagoya, japan. © All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nihon mukashibanashi meii. English. The Yanagita Kunio guide to the japanese folk tale. "Translation of Nihon mukashibanashi meii, compiled under the supervision of Yanagita Kunio and edited by Nihon Hoso Kyokai." T.p. verso. "This book has been produced from camera-ready copy provided by Asian Folklore Studies, Nanzan University, Nagoya,japan."-T.p. verso. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Tales-japan-History and criticism. I. Yanagita, Kunio, 1875-1962. II. Mayer, Fanny Hagin, 1899- III. Nihon Hoso Kyokai. IV. Title. GR340.N52213 1986 398.2'0952 85-45291 ISBN 0-253-36812-X 2 3 4 5 90 89 88 87 86 Contents Preface vii Translator's Notes xiv Acknowledgements xvii About Folk Tales by Yanagita Kunio xix PART ONE Folk Tales in Complete Form Chapter 1.