Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

A Set of Japanese Word Cohorts Rated for Relative Familiarity

A SET OF JAPANESE WORD COHORTS RATED FOR RELATIVE FAMILIARITY Takashi Otake and Anne Cutler Dokkyo University and Max-Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT are asked to guess about the identity of a speech signal which is in some way difficult to perceive; in gating the input is fragmentary, A database is presented of relative familiarity ratings for 24 sets of but other methods involve presentation of filtered or noise-masked Japanese words, each set comprising words overlapping in the or faint signals. In most such studies there is a strong familiarity initial portions. These ratings are useful for the generation of effect: listeners guess words which are familiar to them rather than material sets for research in the recognition of spoken words. words which are unfamiliar. The above list suggests that the same was true in this study. However, in order to establish that this was 1. INTRODUCTION so, it was necessary to compare the relative familiarity of the guessed words and the actually presented words. Unfortunately Spoken-language recognition proceeds in time - the beginnings of we found no existing database available for such a comparison. words arrive before the ends. Research on spoken-language recognition thus often makes use of words which begin similarly It was therefore necessary to collect familiarity ratings for the and diverge at a later point. For instance, Marslen-Wilson and words in question. Studies of subjective familiarity rating 1) 2) Zwitserlood and Zwitserlood examined the associates activated (Gernsbacher8), Kreuz9)) have shown very high inter-rater by the presentation of fragments which could be the beginning of reliability and a better correlation with experimental results in more than one word - in Zwitserlood's experiment, for example, language processing than is found for frequency counts based on the fragment kapit- which could begin the Dutch words kapitein written text. -

Nepal Side, We Must Mention Prof

The Journal of Newar Studies Swayambhv, Ifliihichaitya Number - 2 NS 1119 (TheJournal Of Newar Studies) NUmkL2 U19fi99&99 It has ken a great pleasure bringing out the second issue of EdltLlo the journal d Newar Studies lijiiiina'. We would like to thank Daya R Sha a Gauriehankar Marw&~r Ph.D all the members an bers for their encouraging comments and financial support. ivc csp~iilly:-l*-. urank Prof. Uma Shrestha, Western Prof.- Todd ttwria Oregon Univers~ty,who gave life to this journd while it was still in its embryonic stage. From the Nepal side, we must mention Prof. Tej Shta Sudip Sbakya Ratna Kanskar, Mr. Ram Shakya and Mr. Labha Ram Tuladhar who helped us in so many ways. Due to our wish to publish the first issue of the journal on the Sd Fl~ternatioaalNepal Rh&a levi occasion of New Nepal Samht Year day {Mhapujii), we mhed at the (INBSS) Pdand. Orcgon USA last minute and spent less time in careful editing. Our computer Nepfh %P Puch3h Amaica Orcgon Branch software caused us muble in converting the files fm various subrmttd formats into a unified format. We learn while we work. Constructive are welcome we try Daya R Shakya comments and will to incorporate - suggestions as much as we can. Atedew We have received an enormous st mount of comments, Uma Shrcdha P$.D.Gaurisbankar Manandhar PIID .-m -C-.. Lhwakar Mabajan, Jagadish B Mathema suggestions, appreciations and so forth, (pia IcleI to page 94) Puma Babndur Ranjht including some ~riousconcern abut whether or not this journal Rt&ld Rqmmtatieca should include languages other than English. -

Perfect-Traj.Pdf

Aspect shifts in Indo-Aryan and trajectories of semantic change1 Cleo Condoravdi and Ashwini Deo Abstract: The grammaticalization literature notes the cross-linguistic robustness of a diachronic pat- tern involving the aspectual categories resultative, perfect, and perfective. Resultative aspect markers often develop into perfect markers, which then end up as perfect plus perfective markers. We intro- duce supporting data from the history of Old and Middle Indo-Aryan languages, whose instantiation of this pattern has not been previously noted. We provide a semantic analysis of the resultative, the perfect, and the aspectual category that combines perfect and perfective. Our analysis reveals the change to be a two-step generalization (semantic weakening) from the original resultative meaning. 1 Introduction The emergence of new functional expressions and the changes in their distribution and interpretation over time have been shown to be systematic across languages, as well as across a variety of semantic domains. These observations have led scholars to construe such changes in terms of “clines”, or predetermined trajectories, along which expressions move in time. Specifically, the typological literature, based on large-scale grammaticaliza- tion studies, has discovered several such trajectorial shifts in the domain of tense, aspect, and modality. Three properties characterize such shifts: (a) the categories involved are sta- ble across cross-linguistic instantiations; (b) the paths of change are unidirectional; (c) the shifts are uniformly generalizing (Heine, Claudi, and H¨unnemeyer 1991; Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994; Haspelmath 1999; Dahl 2000; Traugott and Dasher 2002; Hopper and Traugott 2003; Kiparsky 2012). A well-known trajectory is the one in (1). -

The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos To cite this version: Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos. The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual mean- ings. Zlatka Guentcheva. Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, pp.375 - 412, 2016, 9789027267610. 10.1075/slcs.172.12don. halshs-01424956 HAL Id: halshs-01424956 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01424956 Submitted on 6 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings, in Guentchéva, Zlatka (ed.), Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, 2016, p. 375-411 (the published paper miss examples written in Armenian) The aorist in Modern Armenian: core values and contextual meanings Anaïd Donabédian (SeDyL, INALCO/USPC, CNRS UMR8202, IRD UMR135) Introduction Comparison between particular markers in different languages is always controversial, nevertheless linguists can identify in numerous languages a verb tense that can be described as aorist. Cross-linguistic differences exist, due to the diachrony of the markers in question and their position within the verbal system of a given language, but there are clearly a certain number of shared morphological, syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic features. -

Shigisan Engi Shigisan Engi Overview

Shigisan engi Shigisan engi Overview I. The Shigisan engi or Legends of the Temple on Mount Shigi consists of three handscrolls. Scroll 1 is commonly called “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 2 “The Exorcism of the Engi Emperor,” and Scroll 3 “The Story of the Nun.” These scrolls are a pictorial presentation of three legends handed down among the common people. These legends appear under the title “Shinano no kuni no hijiri no koto” (The Sage of Shinano Province) in both the Uji sh¯ui monogatari (Tales from Uji) and the Umezawa version of the Kohon setsuwash¯u (Collection of Ancient Legends). Since these two versions of the legends are quite similar, one is assumed to be based on the other. The Kohon setsuwash¯u ver- sion is written largely in kana, the phonetic script, with few Chinese characters and is very close to the text of the Shigisan engi handscrolls. Thus, it seems likely that there is a deep connection between the Shigisan engi and the Kohon setsuwash¯u; one was probably the basis for the other. “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 1 of the Shigisan engi, lacks the textual portion, which has probably been lost. As that suggests, the Shigisan engi have not come down to us in their original form. The Shigisan Ch¯ogosonshiji Temple owns the Shigisan engi, and the lid of the box in which the scrolls were stored lists two other documents, the Taishigun no maki (Army of Prince Sh¯otoku-taishi) and notes to that scroll, in addition to the titles of the three scrolls. -

PDF Generated By

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Dec 07 2015, NEWGEN 3 Vajrayāna Traditions in Nepal Todd Lewis and Naresh Man Bajracarya Introduction The existence of tantric traditions in the Kathmandu Valley dates back at least a thousand years and has been integral to the Hindu– Buddhist civi- lization of the Newars, its indigenous people, until the present day. This chapter introduces what is known about the history of the tantric Buddhist tradition there, then presents an analysis of its development in the pre- modern era during the Malla period (1200–1768 ce), and then charts changes under Shah rule (1769–2007). We then sketch Newar Vajrayāna Buddhism’s current characteristics, its leading tantric masters,1 and efforts in recent decades to revitalize it among Newar practitioners. This portrait,2 especially its history of Newar Buddhism, cannot yet be more than tentative in many places, since scholarship has not even adequately documented the textual and epigraphic sources, much less analyzed them systematically.3 The epigraphic record includes over a thousand inscrip- tions, the earliest dating back to 464 ce, tens of thousands of manuscripts, the earliest dating back to 998 ce, as well as the myriad cultural traditions related to them, from art and architecture, to music and ritual. The religious traditions still practiced by the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley represent a unique, continuing survival of Indic religions, including Mahāyāna- Vajrayāna forms of Buddhism (Lienhard 1984; Gellner 1992). Rivaling in historical importance the Sanskrit texts in Nepal’s libraries that informed the Western “discovery” of Buddhism in the nineteenth century (Hodgson 1868; Levi 1905– 1908; Locke 1980, 1985), Newar Vajrayāna acprof-9780199763689.indd 872C28B.1F1 Master Template has been finalized on 19- 02- 2015 12/7/2015 6:28:54 PM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Dec 07 2015, NEWGEN 88 TanTric TradiTions in Transmission and TranslaTion tradition in the Kathmandu Valley preserves a rich legacy of vernacular texts, rituals, and institutions. -

The Journey of Nepal Bhasa from Decline to Revitalization — Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies May 2018

Center for Sami Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Science and Education The Journey of Nepal Bhasa From Decline to Revitalization — Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies May 2018 The Journey of Nepal Bhasa From Decline to Revitalization A thesis submitted by Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies The Centre of Sami Studies (SESAM) Faculty of Humanities, Social Science and Education UIT The Arctic University of Norway May 2018 Dedicated to My grandma, Nani Maya Dangol & My children, Prathamesh and Pranavi मा車भाय् झीगु म्हसिका ख: (Ma Bhay Jhigu Mhasika Kha) ‘MOTHER TONGUE IS OUR IDENTITY’ Cover Photo: A boy trying to spin the prayer wheels behind the Harati temple, Swoyambhu. The mantra Om Mane Padme Hum in these prayer wheels are written in Ranjana lipi. The boy in the photo is wearing the traditional Newari dress. Model: Master Prathamesh Prakash Shrestha Photo courtesy: Er. Rashil Maharjan I ABSTRACT Nepal Bhasa is a rich and highly developed language with a vast literature in both ancient and modern times. It is the language of Newar, mostly local inhabitant of Kathmandu. The once administrative language, Nepal Bhasa has been replaced by Nepali (Khas) language and has a limited area where it can be used. The language has faced almost 100 years of suppression and now is listed in the definitely endangered language list of UNESCO. Various revitalization programs have been brought up, but with limited success. This main goal of this thesis on Nepal Bhasa is to find the actual reason behind the fall of this language and hesitation of the people who know Nepal Bhasa to use it. -

Ritual Period: a Comparative Study of Three Newar Buddhist Menarche Manuals Christoph Emmricha a University of Toronto, Canada Published Online: 27 Mar 2014

This article was downloaded by: [Christoph Emmrich] On: 14 April 2014, At: 13:57 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/csas20 Ritual Period: A Comparative Study of Three Newar Buddhist Menarche Manuals Christoph Emmricha a University of Toronto, Canada Published online: 27 Mar 2014. To cite this article: Christoph Emmrich (2014) Ritual Period: A Comparative Study of Three Newar Buddhist Menarche Manuals, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 37:1, 80-103, DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2014.873109 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2014.873109 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

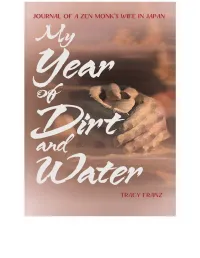

My Year of Dirt and Water

“In a year apart from everyone she loves, Tracy Franz reconciles her feelings of loneliness and displacement into acceptance and trust. Keenly observed and lyrically told, her journal takes us deep into the spirit of Zen, where every place you stand is the monastery.” KAREN MAEZEN MILLER, author of Paradise in Plain Sight: Lessons from a Zen Garden “Crisp, glittering, deep, and probing.” DAI-EN BENNAGE, translator of Zen Seeds “Tracy Franz’s My Year of Dirt and Water is both bold and quietly elegant in form and insight, and spacious enough for many striking paradoxes: the intimacy that arises in the midst of loneliness, finding belonging in exile, discovering real freedom on a journey punctuated by encounters with dark and cruel men, and moving forward into the unknown to finally excavate secrets of the past. It is a long poem, a string of koans and startling encounters, a clear dream of transmissions beyond words. And it is a remarkable love story that moved me to tears.” BONNIE NADZAM, author of Lamb and Lions, co-author of Love in the Anthropocene “A remarkable account of a woman’s sojourn, largely in Japan, while her husband undergoes a year-long training session in a Zen Buddhist monastery. Difficult, disciplined, and interesting as the husband’s training toward becoming a monk may be, it is the author’s tale that has our attention here.” JOHN KEEBLE, author of seven books, including The Shadows of Owls “Franz matches restraint with reflexiveness, crafting a narrative equally filled with the luminous particular and the telling omission. -

Mathias Jenny: the Verb System of Mon

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2005 The verb system of Mon Jenny, Mathias Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-110202 Dissertation Originally published at: Jenny, Mathias. The verb system of Mon. 2005, University of Zurich, Faculty of Arts. Mathias Jenny: The Verb System of Mon Contents Preface v Abbreviations viii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 The Mon people and language 1 1.2 Sources and methodology 8 1.3 Sentence structure 13 1.4 Sentence types 15 1.4.1 Interrogative sentences 15 1.4.2 Imperative sentences 18 1.4.3 Conditional clauses 20 1.5 Phonology of Mon 23 1.5.1 Historical overview 23 1.5.2 From Middle Mon to Modern Mon 26 1.5.3 Modern dialects 30 1.5.4 The phonology of SM 33 1.5.5 Phonology and the writing system 37 2. Verbs in Mon 42 2.1 What are verbs? 42 2.2 The predicate in Mon 43 2.2.1 Previous studies of the verb in Mon 44 2.2.2 Verbs as word class in Mon 47 2.2.3 Nominal predicates and topicalised verbs 49 2.3 Negation 51 2.3.1 Negated statements and questions 51 2.3.2 Prohibitive 58 2.3.3 Summary 59 2.4 Verbal morphology 60 2.4.1 Historical development 60 2.4.2 Modern Mon 65 2.4.3 Summary 67 2.5 Verb classes and types of verbs 67 2.5.1 Transitive and intransitive verbs 68 2.5.2 Aktionsarten 71 2.5.3 Resultative verb compounds (RVC) 75 2.5.4 Existential verbs (Copulas) 77 2.5.4.1 ‹dah› th ‘be something’ 78 2.5.4.2 ‹måï› mŋ ‘be at, stay’ 80 2.5.4.3 ‹nwaÿ› nùm ‘be at, exist, have’ 82 2.5.4.4 ‹(hwa’) seï› (hùʔ) siəŋ ‘(not to) be so’ 86 i Mathias Jenny: The Verb System of Mon 2.5.5 Directionals 88 2.6 Complements of verbs 89 2.6.1 Direct objects 90 2.6.2 Oblique objects 91 2.6.3 Complement clauses 95 3.