Dancing Gods at Godless Festivals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outdoor Club Japan (OCJ) 国際 アウトドア・クラブ・ジャパン Events

Outdoor Club Japan (OCJ) 国際 アウトドア・クラブ・ジャパン Events Norikuradake Super Downhill 10 March Friday to 12 March Monday If you are not satisfied ski & snowboard in ski area. You can skiing from summit. Norikuradake(3026m)is one of hundred best mountain in Japan. This time is good condition of backcountry ski season. Go up to the summit of Norikuradake by walk from the top of last lift(2000m). Climb about 5 hours and down to bottom lift(1500m) about 50 min. (Deta of last time) Transport: Train from Shinjuku to Matsumoto and Taxi from Matsumoto to Norikura-kogen. Return : Bus from Norikura-kogen to Sinshimashima and train to Shinjuku. Meeting Time & Place : 19:30 Shijuku st. platform 5 car no.1 for super Azusa15 Cost : About Yen30000 Train Shinjuku to matsumoto Yen6200(ow) but should buy 4coupon ticket each coupon Yen4190 or You can buy discount ticket shop in town price is similar. (price is non-reserve seat) Taxi about Yen13000 we will share. Return bus Yen1300 and local train Yen680. Inn Yen14000+tax 2 overnight 2 breakfast 1 dinner (no dinner Friday) Japanese room and hot spring! Necessary equipment : Skiers & Telemarkers need a nylon mohair skin. Snowboarders need snowshoes. Crampons(over 8point!) Clothes: Gore-tex jacket and pants, fleece, hut, musk, gloves, sunglasses, headlamp, thermos, lunch, sunscreen If you do not go up to the summit, you can enjoy the ski area and hot springs. 1 day lift pass Yen4000 Limit : 12persons (priority is downhill from summit) In Japanese : 026m)の頂上からの滑降です。 ゲレンデスキーに物足りないスキーヤー、スノーボーダー向き。 山スキーにいいシーズンですが、天気次第なので一応土、日と2日間の時間をとりました。 -

Race 1 1 1 2 2 3 2 4 3 5 3 6 4 7 4 8

TOKYO SUNDAY,MAY 19TH Post Time 10:05 1 ! Race Dirt 1400m THREE−YEAR−OLDS Course Record:31May.08 1:21.9 F&M DES,WEIGHT FOR AGE,MAIDEN Value of race: 9,550,000 Yen 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th Added Money(Yen) 5,000,000 2,000,000 1,300,000 750,000 500,000 Stakes Money(Yen) 0 0 0 Ow. Dearest 2,750,000 S 40004 Life60105M 20101 1 54.0 Kosei Miura(6.3%,21−17−29−265,20th) Turf10001 I 00000 1 Dear Aspen(JPN) Dirt50104L 00000 .Captain Steve(0.47) .Forty Niner F3,ch. Yasuhito Tamura(9.6%,14−15−20−97,10th) Course20101E 00000 Wht. /Keiai Patra /Sachi George 20May.10 Nonomiya Bokujo Wet 00000 5May.13 TOKYO MDN D1400St 2 2 1:26.7 4th/15 Kosei Miura 54.0 454# Printemps Bijou 1:25.7 <5> Himesakura <1 1/4> Earth the Three 20Apr.13 TOKYO MDN D1400St 3 3 1:26.9 2nd/16 Kosei Miura 54.0 454% Seiyu Smile 1:26.9 <NK> Dear Aspen <2 1/2> Denko Arrows 24Dec.12 NAKAYAMA MDN D1200Go 2 4 1:13.4 7th/16 Masaki Katsuura 54.0 450+ Hayabusa Pekochan 1:12.8 <NS> Nikiya Dia <1/2> Mary’s Mie 11Nov.12 FUKUSHIMA MDN D1150St 7 5 DQ&P 1:11.5 (6)14th/16 Kyosuke Maruta 54.0 448* Land Queen 1:10.2 <HD> Erimo Feather <1 1/2> Asuka Blanche 29Jul.12 SAPPORO MDN D1000St 8 8 1:01.4 7th/11 Yusuke Fujioka 54.0 436( Regis 0:59.9 <2> Passion <NK> Lapisblau Ow. -

Fanning the Flames: Fandoms and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan

FANNING THE FLAMES Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan Edited by William W. Kelly Fanning the Flames SUNY series in Japan in Transition Jerry Eades and Takeo Funabiki, editors Fanning the Flames Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan EDITED BY WILLIAM W. K ELLY STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fanning the f lames : fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan / edited by William W. Kelly. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Japan in transition) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6031-2 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7914-6032-0 (pbk. : alk.paper) 1. Popular culture—Japan—History—20th century. I. Kelly, William W. II. Series. DS822.5b. F36 2004 306'.0952'09049—dc22 2004041740 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Locating the Fans 1 William W. Kelly 1 B-Boys and B-Girls: Rap Fandom and Consumer Culture in Japan 17 Ian Condry 2 Letters from the Heart: Negotiating Fan–Star Relationships in Japanese Popular Music 41 Christine R. -

Radicalizing Romance: Subculture, Sex, and Media at the Margins

RADICALIZING ROMANCE: SUBCULTURE, SEX, AND MEDIA AT THE MARGINS By ANDREA WOOD A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Andrea Wood 2 To my father—Paul Wood—for teaching me the value of independent thought, providing me with opportunities to see the world, and always encouraging me to pursue my dreams 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Kim Emery, my dissertation supervisor, for her constant encouragement, constructive criticism, and availability throughout all stages of researching and writing this project. In addition, many thanks go to Kenneth Kidd and Trysh Travis for their willingness to ask me challenging questions about my work that helped me better conceptualize my purpose and aims. Finally, I would like to thank my friends and family who provided me with emotional and financial support at difficult stages in this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................7 ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................9 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................11 -

Elementi Bonaventura Ruperti Storia Del Teatro Giapponese Dalle Origini All’Ottocento Dalle Origini All’Ottocento

elementi Bonaventura Ruperti Storia del teatro giapponese dalle origini all’Ottocento Dalle origini all’Ottocento frontespizio provvisorio Marsilio Indice 9 Introduzione 9 Alternanza di aperture e chiusure 11 Continuità e discontinuità 12 Teatro e spettacolo in Giappone 16 Scrittura e scena 17 Trasmissione delle arti 22 Dal rito allo spettacolo 22 Miti, rito e spettacolo 25 Kagura: musica e danza divertimento degli dei 29 Riti e festività della coltura del riso: tamai, taasobi, dengaku 34 Dal continente all’arcipelago, dai culti locali alla corte imperiale 34 Forme di musica e spettacolo di ascendenza continentale. L’ingresso del buddhismo: gigaku 36 La liturgia buddhista: shōmyō 39 Il repertorio 40 L’universo delle musiche e danze di corte: gagaku 43 Il repertorio 43 Bugaku in copertina 45 Kangen Sakamaki/Tsukioka Kōgyo (1869-1927), 46 Canti e danze Sahoyama, 1901 48 Gli strumenti 49 I dodici suoni e le dodici tonalità 50 Il grande territorio dello spettacolo e lo sviluppo del teatro di rappresentazione: sangaku e sarugaku 53 Jushi 53 Okina © 2015 by Marsilio Editori® s.p.a. in Venezia 54 Ennen 55 Furyuˉ Prima edizione mese 2015 ISBN 978-88-317-xxxx-xx 57 Il nō 57 Definizione e genesi www.marsilioeditori.it 58 Origini e sviluppo storico 61 I trattati di Zeami Realizzazione editoriale Studio Polo 1116, Venezia 61 La poetica del fiore 5 Indice Indice 63 L’estetica della grazia 128 Classicità e attualità - Kaganojō e Tosanojō 65 La prospettiva di un attore 129 Il repertorio 68 Il dopo Zeami: Zenchiku 130 Il palcoscenico 69 L’epoca Tokugawa 131 L’avvento di Takemoto Gidayū - I teatri Takemoto e Toyotake 71 Hachijoˉ Kadensho 131 Un maestro della scrittura: Chikamatsu Monzaemon 71 Palcoscenico e artisti 133 L’opera di Chikamatsu Monzaemon 72 Testo drammatico e struttura 133 I drammi di ambientazione storica (jidaimono) 73 Dialogo rivelatore 134 I drammi di attualità (sewamono): adulteri e suicidi d’amore 75 Tipologie di drammi 136 Ki no Kaion e il teatro Toyotake 82 Il senso del ricreare 136 Testo drammatico e struttura 84 Musica 139 Dopo Chikamatsu. -

Japanese Costume

-s-t JAPANESE COSTUME BY HELEN C. GUNSAULUS Assistant Curator of Japanese Ethnology WQStTY OF IUR0IS L . MCI 5 1923 FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CHICAGO 1923 >7£ VtT3f 7^ Field Museum of Natural History DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Chicago. 1923 Leaflet Number 12 Japanese Costume Though European influence is strongly marked in many of the costumes seen today in the larger sea- coast cities of Japan, there is fortunately little change to be noted in the dress of the people of the interior, even the old court costumes are worn at a few formal functions and ceremonies in the palace. From the careful scrutinizing of certain prints, particularly those known as surimono, a good idea may be gained of the appearance of all classes of people prior to the in- troduction of foreign civilization. A special selection of these prints (Series II), chosen with this idea in mind, may be viewed each year in Field Museum in Gunsaulus Hall (Room 30, Second Floor) from April 1st to July 1st at which time it is succeeded by another selection. Since surimono were cards of greeting exchanged by the more highly educated classes of Japan, many times the figures portrayed are those known through the history and literature of the country, and as such they show forth the costumes worn by historical char- acters whose lives date back several centuries. Scenes from daily life during the years between 1760 and 1860, that period just preceding the opening up of the coun- try when surimono had their vogue, also decorate these cards and thus depict the garments worn by the great middle class and the military (samurai) class, the ma- jority of whose descendents still cling to the national costume. -

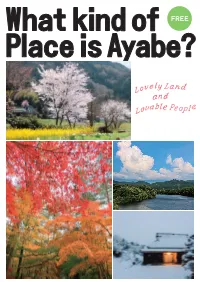

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

Shigisan Engi Shigisan Engi Overview

Shigisan engi Shigisan engi Overview I. The Shigisan engi or Legends of the Temple on Mount Shigi consists of three handscrolls. Scroll 1 is commonly called “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 2 “The Exorcism of the Engi Emperor,” and Scroll 3 “The Story of the Nun.” These scrolls are a pictorial presentation of three legends handed down among the common people. These legends appear under the title “Shinano no kuni no hijiri no koto” (The Sage of Shinano Province) in both the Uji sh¯ui monogatari (Tales from Uji) and the Umezawa version of the Kohon setsuwash¯u (Collection of Ancient Legends). Since these two versions of the legends are quite similar, one is assumed to be based on the other. The Kohon setsuwash¯u ver- sion is written largely in kana, the phonetic script, with few Chinese characters and is very close to the text of the Shigisan engi handscrolls. Thus, it seems likely that there is a deep connection between the Shigisan engi and the Kohon setsuwash¯u; one was probably the basis for the other. “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 1 of the Shigisan engi, lacks the textual portion, which has probably been lost. As that suggests, the Shigisan engi have not come down to us in their original form. The Shigisan Ch¯ogosonshiji Temple owns the Shigisan engi, and the lid of the box in which the scrolls were stored lists two other documents, the Taishigun no maki (Army of Prince Sh¯otoku-taishi) and notes to that scroll, in addition to the titles of the three scrolls. -

A Japanese View of “The Other World” Reflected in the Movie “Departures

13. A Japanese view of the Other World reflected in the movie “Okuribito (Departures)” Keiko Tanita Introduction Religion is the field of human activities most closely related to the issue of death. Japan is considered to be a Buddhist country where 96 million people support Buddhism with more than 75 thousands temples and 300 thousands Buddha images, according to the Cultural Affaires Agency in 2009. Even those who have no particular faith at home would say they are Buddhist when asked during their stay in other countries where religion is an important issue. Certainly, a great part of our cultural tradition is that of Buddhism, which was introduced into Japan in mid-6th century. Since then, Buddhism spread first among the aristocrats, then down to the common people in 13th century, and in the process it developed a synthesis of the traditions of the native Shintoism. Shintoism is a religion of the ancient nature and ancestor worship, not exactly the same as the present-day Shintoism which was institutionalized in the late 19th century in the course of modernization of Japan. Presently, we have many Buddhist rituals especially related to death and dying; funeral, death anniversaries, equinoctial services, the Bon Festival similar to Christian All Souls Day, etc. and most of them are originally of Japanese origin. Needless to say, Japanese Buddhism is not same as that first born in India, since it is natural for all religions to be influenced by the cultures specific to the countries/regions where they develop. Japanese Buddhism, which came from India through the Northern route of Tibet and China developed into what is called Mahayana Buddhism which is quite different from the conservative Theravada traditions found in Thai, Burmese, and Sri Lankan Buddhism, which spread through the Southern route. -

Rising Loaves Anthology 2019 0.Pdf

Cover Art by: Magory Collado "Lawrence Student Writing Workshop: The Rising Loaves” is hosted by the Lawrence History Center, developed in collaboration with Andover Bread Loaf, and funded in part by the Catherine McCarthy Trust, the Essex County Community Foundation Greater Lawrence Summer Fund, W. Dean and Sy Eastman, the Pringle Foundation, the Stearns and Russell Trusts, Rogers Family Foundation, Andover Bread Loaf, and the Lawrence Public School lunch program. A Letter from the Program Directors …….………………...…….………………..3 Student and Writing Leader Work Brianna Anderson ………………………………….……....……..………..……5 Jhandaries Ayala ………………………………….……....…………...…...……5 Sheila Barry ………………………………….……....……………..……………6 Angelique Ceballos Cardona ………………………………….…….………..…6 Magory Collado ………………………………….……....………………………7 Kelley De Leon ………………………………….……....……….………………8 Michael De Leon ………………………………….……....………..……………9 Isabella Delgado ………………………………….……....…………..………...10 Jennifer Escalante ………………………………….……....………..…………10 Julien Felipe ………………………………….……....………………………….11 Angell Flores …………………………………………………….………..…..…11 Anelyn Gomez ………………………………….……........…….………………12 Karen Gonzalez ………………………………….………....…….……..………12 Katarina Guerrero ………………………………….……........………..………12 Mary Guerrero ………………………………………………..….……..………13 Lee Krishnan ………………………………….……....…………….……..……13 Breison Lopez ………………………………….……....……………….………14 Edin Macario ………………………………….……....………………..….……14 Manuel Maurico ………………………………….……....…………..…………15 Mekhi Mendoza ………………………………….……....…………..…………15 Jennifer Merida ………………………………….……....……………………...15 -

JFKL Publication 11-01.Eps

Past, Present and Future: The 30th Anniversary of the Japan Foundation, Kuala Lumpur Greetings from the Director The Japan Foundation was established in 1972 with the main goal of cultivating friendship and ties between Japan and the world through culture, language, and dialogue. The Kuala Lumpur ofice known as The Japan Foundation Kuala Lumpur Liaison Ofice was established at Wisma Nusantara, off Jalan P. Ramlee on 3 October 1989 as the third liaison ofice in SEA countries, following Jakarta and Bangkok. The liaison ofice was upgraded to Japan Cultural Centre Kuala Lumpur with Prince Takamado attending the opening ceremony on 14 February 1992. Japanese Language Centre Kuala Lumpur was then opened at Wisma Nusantara on 20 April 1995. In July 1998, the ofice moved to Menara Citibank, Jalan Ampang and then once more to our current ofice in Northpoint, Mid-Valley in September 2008. Since the establishment, the Japan Foundation, Kuala Lumpur (JFKL) has been working on various projects such as introducing Japanese arts and culture to Malaysia and vice versa. JFKL has also closely worked with the Ministry of Education to form a solid foundation of Japanese Language Education especially in Malaysian secondary schools and conducted various seminars and trainings for local Japanese teachers. We have also been supporting Japanese studies and promoting dialogues on common international issues. The past 30 years have deinitely been a long yet memorable journey in bringing the cultures of the two countries together. The cultural exchange with Malaysia has become more signiicant and crucial as Japan heads towards a multi-cultural society and there is a lot to learn from Malaysia. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first.