Swaziland Urban Development Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swaziland-VMMC-And-EIMC-Strategy

T ABLE OF C ONTENTS Table of Contents .........................................................................................................................................................................................i List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................................................................. iii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................................................ iii List of Boxes .............................................................................................................................................................................................. iii List of Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................................................... iv Foreword ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

Baphalali Swaziland Red Cross Society Clinics & Divisions Performance

BAPHALALI SWAZILAND RED CROSS SOCIETY CLINICS & DIVISIONS PERFORMANCE 2013 PREPARED BY: ELLIOT JELE PROGRAMMES MANAGER DATE: 8TH AUGUST, 2014 i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................................ II 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 1 2. PROGRAMMES DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................... 2 3. ACHIEVEMENTS IN 2013 ............................................................................................................................... 2 3.1. HEALTH AND SOCIAL SERVICES ................................................................................................................. 2 3.1.1. GOAL- HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES ........................................................................................................ 2 3.1.2. OBJECTIVES - HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES .............................................................................................. 3 3.1.3. OVERALL HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES ACHIEVEMENTS .......................................................................... 3 3.1.4. ACHIEVEMENT PER PROGRAME COMPONENT, & OUTCOME LEVEL ....................................................... 3 ORPHANED AND VULNERABLE CHILDREN ....................................................................................................... -

2000 334000 336000 338000 340000 342000 31°16'0"E 31°17'0"E 31°18'0"E 31°19'0"E 31°20'0"E 31°21'0"E 31°22'0"E 31°23'0"E 31°24'0"E 31°25'0"E

326000 328000 330000 332000 334000 336000 338000 340000 342000 31°16'0"E 31°17'0"E 31°18'0"E 31°19'0"E 31°20'0"E 31°21'0"E 31°22'0"E 31°23'0"E 31°24'0"E 31°25'0"E GLIDE number: TC-2021-000008-MOZ Activation ID: EMSR495 Int. Charter call ID: N/A Product N.: 04MANZINI, v2 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 4 7 7 Manzini - ESWATINI 0 0 7 7 Storm - Situation as of 30/01/2021 S " 0 ' Grading - Overview map 01 7 2 ° 6 2 S " 0 Mpumalanga ' Maputo 7 2 ° 6 2 Maputo^ Mozambique Channel Baia de Hhohho Maputo Mozambique Ekukhanyeni SouthMaputo Africa 03 Mozambique Channel Mbabane Manzini 05 ^ 0 0 (! Eswatini 0 0 04 0 0 2 2 7 7 0 0 Manzini INDIAN 7 7 OCEAN S " Lubombo 0 ' 8 2 ° 6 o 2 ut S p " a 0 ' M 8 2 ° 6 Ludzeludze 2 20 Shiselweni Kwazulu-Natal km Cartographic Information 1:25000 Full color A1, 200 dpi resolution 0 0.5 1 2 km 0 0 0 0 Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 36S map coordinate system 0 0 0 0 7 7 Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system S 0 0 " 7 7 0 ± ' 9 2 ° 6 2 S " 0 ' 9 2 ° Legend 6 2 Crisis Information Transportation Grading Facilities Grading Hydrography Road, Damaged Dam, Damaged River Blocked road / interruption Road, Possibly damaged General Information Stream Flooded Area Area of Interest (30/01/2021 07:55 UTC) Railway, Damaged Lake Detail map Flood trace Highway, No visible damage Manzini North Not Analysed Built Up Grading Primary Road, No visible damage Manzini Destroyed Administrative boundaries Secondary Road, No visible damage Possibly damaged Province Local Road, No visible damage Placenames Cart Track, No visible damage ! Placename Detail 02 Long-distance railway, No visible damage a Airfield runway, No visible damage n Land Use - Land Cover a Matsapha ! w Manzini Features available in the vector package h ! s Consequences within the AOI u s Possibly Total Total in u Destroyed Damaged 0 Lobamba 0 damaged* affected** AOI L 0 0 S " 0 0 ha 13.8 0 Flooded area ' 8 8 0 3 6 Lomdzala 6 ha 44.1 ° Flood trace 0 0 6 2 7 7 S Estimated population 573 177,811 " 0 ' 0 Built-up No. -

Swaziland Country Operational Plan 2018 Strategic Direction Summary

SWAZILAND Country Operational Plan (COP) 2018 Strategic Direction Summary March 29, 2018 Acronym and Word List A Adolescents AE Adverse Event AG Adolescent Girls AGYW Adolescent Girls and Young Women ALHIV Adolescents Living with HIV ANC Antenatal Clinic APR Annual Program Results ARROWS ART Referral, Retention, and Ongoing Wellness Support ARV Antiretroviral ART Antiretroviral Therapy ASLM African Society for Laboratory Medicine C Children C/A Children/Adolescents CAG Community Adherence Group CANGO Coordinating Assembly of Non-Governmental Organizations CCM Country Coordinating Mechanism CEE Core Essential Element CHAI Clinton Health Access Initiative CIHTC Community-Initiated HIV Testing and Counseling CMIS Client Management Information System CMS Central Medical Stores CoAg Cooperative Agreement CQI Continuous Quality Improvement CS(O) Civil Society (Organizations) DBS Dried Blood Spot DQA Data Quality Assessment DSD Direct Service Delivery E Swazi Emalangeni (1 lilangeni equals 1 rand) ECD Early Childhood Development EID Early Infant Diagnosis eNSF extended National Multi-Sectoral Strategic Framework for HIV & AIDS EQA External Quality Assessment DMPPT Decision Makers Program Planning Toolkit EU European Union FDC Fixed dose combination FDI Foreign Direct Investment FP Family Planning FSW Female Sex Workers GBV Gender Based Violence GHSP Global Health Services Partnership GKoS Government of the Kingdom of Swaziland GF Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria GDP Gross Domestic Product GNI Gross National Income HC4 HIV -

Page 1 2018 NATIONAL ELECTIONS

2018 NATIONAL ELECTIONS - POLLING STATIONS REGION INKHUNDLA POLLING DIVISION HHOHHO HHUKWINI Dlangeni HHUKWINI KaSiko HHUKWINI Lamgabhi HHUKWINI Lamgabhi HHUKWINI Sitseni LOBAMBA Elangeni LOBAMBA Ezulwini LOBAMBA Ezulwini LOBAMBA Ezulwini LOBAMBA Lobamba LOBAMBA Nkhanini LOBAMBA Nkhanini LOBAMBA Zabeni LOBAMBA Zabeni MADLANGEMPISI Dvokolwako / Ekuphakameni MADLANGEMPISI Dvokolwako / Ekuphakameni MADLANGEMPISI Ekukhulumeni/ Mandlangempisi MADLANGEMPISI Ekukhulumeni/ Mandlangempisi MADLANGEMPISI Gucuka MADLANGEMPISI Mavula MADLANGEMPISI Nyonyane/ Maguga MADLANGEMPISI Tfuntini/Buhlebuyeza MADLANGEMPISI Tfuntini/Buhlebuyeza MADLANGEMPISI Tfuntini/Buhlebuyeza MADLANGEMPISI Tfuntini/Buhlebuyeza MADLANGEMPISI Zandondo MADLANGEMPISI Zandondo MAPHALALENI Dlozini MAPHALALENI Madlolo MAPHALALENI Maphalaleni MAPHALALENI Mcengeni MAPHALALENI Mfeni MAPHALALENI Nsingweni MAPHALALENI Nsingweni MAYIWANE Herefords MAYIWANE Mavula MAYIWANE Mfasini MAYIWANE Mkhuzweni MAYIWANE Mkhuzweni MAYIWANE Mkhweni MBABANE EAST Fontein MBABANE EAST Fontein MBABANE EAST Mdzimba/Lofokati MBABANE EAST Mdzimba/Lofokati MBABANE EAST Msunduza MBABANE EAST Msunduza MBABANE EAST Msunduza MBABANE EAST Sidwashini MBABANE EAST Sidwashini MBABANE EAST Sidwashini MBABANE EAST Sidwashini MBABANE WEST Mangwaneni MBABANE WEST Mangwaneni MBABANE WEST Mangwaneni MBABANE WEST Manzana MBABANE WEST Nkwalini MBABANE WEST Nkwalini MBABANE WEST Nkwalini MBABANE WEST Nkwalini MHLANGATANE Emalibeni MHLANGATANE Mangweni MHLANGATANE Mphofu MHLANGATANE Mphofu MHLANGATANE Ndvwabangeni MHLANGATANE -

CBD Sixth National Report

SIXTH NATIONAL REPORT i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Eswatini’s Sixth National Report (6NR) to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (UNCBD) has been compiled by the Project Management Unit. The 6NR is a compilation of the contributions that have been made by the different stakeholders that are working on the issues that are in relation to the country’s customized Aichi Targets, as highlighted in the National Biodiversity Strategy Action Plan, Two (NBSAP 2). Data collection from stakeholders was done through the bilateral consultative meetings that were held between stakeholders and the project team, the regional workshops and a national workshop. The compilation of the 6NR has been managed and supervised by Ms. Hlobsile Sikhosana, who is the UNCBD Focal Point and Chief Environmental Coordinator in the Ministry of Tourism and Environmental Affairs. Special appreciation is extended to Mr. Emmanuel Dlamini, who is the Principal Secretary of the Ministry of Tourism and Environmental Affairs. Also appreciated are the members of the Project Steering Committee and the members of the Technical Committee. We further acknowledge the support and guidance from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) especially from Mr Antony Kamau. The acknowledged project team and committees’ members that played a significant role in compiling the report are: 1. Project Team: - Mr Thabani Mazibuko, Mr Prince Mngoma, Mrs Xolile Lokotfwako, Mr Mpendulo Hlandze, Ms Baphelele Dlamini and Mr Lindani Mavimbela (Lead Consultant). 2. Project Steering Committee: - Ms Constance Dlamini, Ms Sanelisiwe Mamba, Ms Turu Dube, Mr Sifiso Msibi, Mr Vumile Magimba, Mr Freddy Magagula, Mr Christopher Mthethwa, Mr Musa Mbingo, Mr Sandile Gumede, Mr Leslie Balinda, Mr Stephen Khumalo, Mr Bongani Magongo and Dr Themb’alilahlwa Mahlaba. -

THE STATE of WASH FINANCING in EASTERN and SOUTHERN AFRICA Eswatini Country Level Assessment

eSwatini THE STATE OF WASH FINANCING IN EASTERN AND SOUTHERN AFRICA Eswatini Country Level Assessment 1 Authors: Oliver Jones, Oxford Policy Management, in collaboration with Agua Consult and Blue Chain Consulting, Oxford, UK. Reviewers: Samuel Godfrey and Bernard Keraita, UNICEF Regional Office for Eastern and Southern Africa, Nairobi, Kenya and Boniswa Dladla (UNICEF Eswatini Country Office). Acknowledgement The author wishes to thank all other contributors from the UNICEF Eswatini Country Office, Government of the Kingdom of Eswatini and development partners. Special thanks go to UNICEF Eswatini for facilitating the data collection process in-country. September 2019 Table of contents The State of WASH Financing in Eastern and Southern Africa Eswatini Country Level Assessment Table of contents List of abbreviations v 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Methodology 1 1.3 Caveats 2 1.4 Report structure 3 2 Country Context 4 2.1 History/geography 4 2.2 Demography 4 2.3 Macroeconomy 5 2.4 Private Sector Overview 6 2.5 Administrative setup 7 3 WASH Sector Context 8 3.1 Access to WASH Services 8 3.2 Institutional Structures 10 3.3 WASH sector policies, strategies and plans 11 3.4 WASH and Private Sector Involvement 12 4 Government financing of WASH services 13 4.1 Recent Trends 13 4.2 Sector Financing of Strategies and Plans 16 4.3 Framework for donor engagement in the sector 17 5 Donor financing of WASH services 19 5.1 Recent trends 19 5.2 Main Modalities 22 5.3 Coordination of donor support 23 6 Consumer financing of WASH services 24 -

Swaziland Government Gazette Extraordinary

Swaziland Government Gazette Extraordinary VOL. XLVI] MBABANE, Friday, MAY 16th 2008 [No. 67 CONTENTS No. Page PART C - LEGAL NOTICE 104. Registration Centres For the 2008 General Elections................................................... SI PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY 442 GENERAL NOTICE NO. 25 OF 2008 VOTERS REGISTRATION ORDER, 1992 (King’s Order in Council No.3 of 1992) REGISTRATION CENTRES FOR THE 2008 GENERAL ELECTIONS (Under Section 5(4)) Short title and commencement (1) This notice shall be cited as the Registration Centres Notice, 2008. (2) This general notice shall come into force on the date of publication in the Gazette. Registration centres for the 2008general elections It is notified for general information that the registration of all eligible voters for the 2008 general elections shall be held at Imiphakatsi (chiefdoms) and at the registration centres that have been listed in this notice; REGISTRATION CENTRES HHOHHO REGION CODE CODE CODE CHIEFDOM / POLLING Sub polling REGION INKHUNDLA STATION station 01 HHOHHO 01 HHUKWINI 01 Dlangeni 01 HHOHHO 01 HHUKWINI 02 Lamgabhi 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 01 Elangeni 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 02 Ezabeni 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 03 Ezulwini 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 04 Lobamba 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 05 Nkhanini 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 01 Buhlebuyeza 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 02 KaGuquka 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 03 Kuphakameni/ Dvokolwako 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 04 Mzaceni 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 05 Nyonyane / KaMaguga 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 06 Zandondo 01 HHOHHO 04 MAPHALALENI 01 Edlozini 443 -

Anthropogenic Pollution of the Lusushwana River at Matsapha, and Prospects for Its Control: Kingdom of Swaziland (Eswatini) By: Phindile Precious Mhlanga-Mdluli

This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ Loughborough University, Department of Civil & Building Engineering, United Kingdom. Anthropogenic Pollution of the Lusushwana River at Matsapha, and Prospects for its Control: Kingdom of Swaziland (eSwatini) By: Phindile Precious Mhlanga-Mdluli A Doctoral Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of a Doctor of Philosophy of Loughborough University, United Kingdom January, 2012 ©Mhlanga-Mdluli, P.P. 2012 Acknowledgements ii Acknowledgements Unsurpassed gratitude is to my Lord and Saviour, for his never ending favour upon my study. A thesis of this magnitude could have not been accomplished by my intelligence alone, for all man has is limited knowledge, but that of God is infinite and transcendent knowledge. I am deeply grateful to my supervisor Mr. Mike Smith for his knowledgeable supervision and tactful guidance and wisdom. Literature on guidance for obtaining a PhD discourages one-man supervision, but Mike is an experienced and versatile Supervisor, and I cherish the good working relationship we maintained throughout my term of study. I thank Professor M.S. Sohail for his support and for keeping me focused. He told me the first day I set foot in Loughborough that ―it is your research and you have to do it yourself‖. His words lingered on and they remained a source of inspiration throughout my study. -

The Kingdom of Swaziland

THE KINGDOM OF SWAZILAND MASTERPLAN TOWARDS THE ELIMINATION OF NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES - 2015- 2020 Foreword Acknowledgements Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 1 LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................. 5 PART 1: SITUATION ANALYSIS ....................................................................................... 10 1.1 Country profile ......................................................................................................... 10 1.1.1 Geographical characteristics ............................................................................... 10 1.1 .2 PHYSICAL FEATURES AND CLIMATIC CONDITIONS ....................................... 11 1.1.3. ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURES, DEMOGRAPHY AND COMMUNITY STRUCTURES ................................................................................................................... 12 1.3.2 Population ............................................................................................................. 13 Health Information System ........................................................................................... 25 Health workforce ........................................................................................................... 26 Medical products .......................................................................................................... -

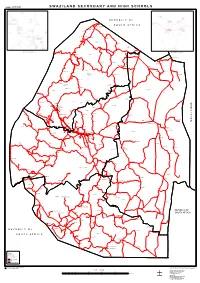

Secondary Schools

Scale 1:250,000 S W A Z I L A N D S E C O N D A R Y A N D H I G H S C H O O L S R E P U B L I C O F S O U T H A F R I C A Timphisini Mlumati ! ! Sidvwashini Meth. ! Mswati II ! Ludzibini !( Ntfonjeni Hhelehhele! ! Kudvwaleni !( Mayiwane ! Vusweni ! Ntsinini ! Mangweni ! Herefords Malibeni ! ! Buhleni !( INSERT- MBABANE SCHOOLS Mpofu INSERT- MANZINI SCHOOLS Havelock Mine ! ! Piggs Peak Central Mzimnene ! !( Mhlatane ! Mavula Central Lomahasha Central !( ! Nkalashane ! Kubongeni !( Nyakatfo Ndzingeni !( ! Mananga College ! Tfuntini Sikhunyana ! ! Mbeka Mbeka Madzanga Mhlume ! !( !( ! Magobodvo ! Kwaliweni !( Mafucula Fundukuwela Vuvulane !( !( ! Nkonyeni !( Madlangempisi Maguga Dam ! Majembeni ! ! Luvinjelweni ! Nkhaba ! Nkalangeni Zandondo Dvokolwako !( !( ! Maphalaleni ! Jubukweni !( Ngomane Hawane Mnjoli ! ! ! Lusoti ! Mbuluzi ! Motshane Mliba ! St Florence ! Dlalisile ! Khuphuka ! ! Nsingweni Nsukumbili ! ! Londunduma Sikanye ! !( Woodlands Mncozini E !( ! KaSchiele U ! Sidvokodvo ! !Sifundzani Vusweni ! Nhlanganisweni !( ! St Mark'sFonteyn Nkiliji Luve SAIM ! ! Q ! ! St Franci!(s ! ! I Mater Dolorosa!!(KaBoyce John Wesle!y Mhlahlo Mdzimba ! B ! Sigangeni M ! Kukhanyeni Sigombeni ! Lundzi Setsembiso sebunye A !( ! !( Ntandweni !( C Somjalose ! Siphocosini O ! Purity Ezulwini ! Sitsatsaweni !( Mpaka !( ! Malunge M ! Malindza School for the Deaf ! ! Mantabeni ! Langeni MatsetsaKaLanga ! !! Zombodze Moyeni Mpuluzi ! Mbekelweni ! ! ! Assemblies of GodSiteki Nazarene St Mary's ! ! !Lubombo Central ! ! Lobamba National St Joseph's ! Good -

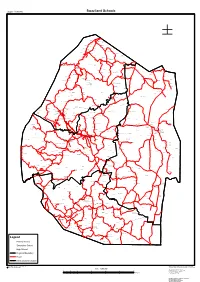

Swaziland Schools

Scale 1:200,000 Swaziland Schools Mashobeni North ! ± Mvembili ! Mvembili ! Mlumati Timphisini !! Timphisin!i ! Mlumati Nhlambeni ! Sidvwashini Ngonini Estates ! ! !Sidvwashini Nkonjane Ndlalambi ! ! Hhohho A.M.E. ! Matibakhulu Lufafa ! ! Hhelehhele Mbasheni ! ! Mcuba Mayiwane ! !( ! Ntfonjeni Ntfonjen!i Nkonjaneni ! ! Kudvwaleni !( Mavula Pisgah ! Gobolondlo ! Kujabuleni Mshingishingini ! ! Mhlangatane ! VusweniVusweni ! ! Zinyane ! Ntsinini Ntsinini Lomhlalane !! ! Phophonyana ! Lugongolwane ! Mkhuzweni ! Nhlanguyavuka Herefords ! ! Ntabinezimpisi ! ! Herefords Manjengeni ! ! Mangweni !( Buhleni Royal ! Matfuntini ! ! Bulembu ! Luvuno Mpofu Peak Central ! ! Havelock Mine ! ! Ludlawini Mavula ! Havelock Mine ! ! ! Mpofu Herbert Stanley ! The Peak School !( ! Mhlatane ! Kuthuleni Peak Nazarene ! ! Njaliba ! !( Lomahasha Ngowane ! ! Assemblies Rosenberg ! ! Cetjwayo Tshaneni Nkalashane ! ! ! ! Njakeni Mafusini ! Tsambokhulu ! ! Mgululu Kujabuleni Holiness Kubongeni ! ! Ndzingeni !( ! Ndzingeni !( Nginamadvolo ! ! Luhlangotsini ! Mananga Sikhunyana ! ! Luhhumaneni Bulandzeni Nkambeni ! ! ! Mbokojwana St Aidan's Madzanga MhlumeMhlume ! ! ! !! Mangedla Magobodvo ! ! ! St Benedict St Peregrine'sBulandzeni ! ! Kuthuleni ! NgowaneKwaliweni Kwaliweni Mafucula St Paul's Anglican !( ! ! ! Fundukuwela Vuvulane !( !( ! !Vuvulane Zwide Kufikeni Bhalekane ! ! Mpumalanga ! ! !( Madlangempisi Buhlebuyeza Majembeni Maguga ! ! ! Melete ! ! Maguga St Manettus ! ! Kutfunyweni Majembeni ! ! Kuhlahla ! ! Nokwane !Malandzela ! Mnyokane Manzana ! ! NkhabaNkhaba