Social Class and Marxism in Twenty One Pilots' Trench

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economics in Music in the Pop Culture Era

Perspectives on Economic Education Research, 2018, 11(1) 41-57 Journal homepage: cobhomepages.cob.isu.edu/peer/ From The Beatles to Twenty One Pilots: Economics in Music in the Pop Culture Era Brian O’Roarka, Kim Holderb, G. Dirk Mateerc1 aSocial Sciences Department, Robert Morris University, United States bUWG Center for Economic Education & Financial Literacy, Department of Economics, University of West Georgia, United States cDepartment of Economics, University of Arizona, United States, [email protected] Abstract Economists have explored methods of using media in the classroom for decades. One of the most common forms of media used is music. This paper adds to ongoing efforts in economics to link music directly to course content by creating a database of each year’s best song since 1964. The database provides an historical timeline to help instructors connect economic events from the past with the music of that time-period. For each song selected, key economics concepts are highlighted and a sample of the relevant lyrics are provided. Key Words: economic education, economic history, music, economics of culture JEL Codes: A10, A22, E20, N00, Z11 1 Corresponding author. O’Roark, Holder, Mateer/Perspectives on Economic Education Research, 2018, 11(1) 41-57 1. Introduction Learning about economics is understandably difficult for students. One of the primary issues they face is their lack of familiarity with the material. Elasticity, utility, subjective value, business cycles and many other terms are akin to a foreign language for most students. In addition, a general shortage of real world experience makes connecting students to the economic lexicon even more trying. -

U2 Metallica Red Hot Chili Peppers Eric Church Garth Brooks

Gross Average Average Total Average Cities Rank Millions Artist Ticket Price Tickets Tickets Gross Shows Agency 1 118.1 U2 119.12 61,973 991,565 7,382,401 16/19 Live Nation Global Touring 2 68.7 Metallica 101.08 52,251 679,266 5,281,339 13/15 Artist Group International 3 60.5 Red Hot Chili Peppers 84.96 14,533 712,099 1,234,694 49/55 WME 4 54.5 Eric Church 60.90 14,671 894,909 893,443 61/63 WME 5 48.0 Garth Brooks 65.02 61,588 739,056 4,004,674 12/48 WME 6 39.1 Bon Jovi 84.86 16,456 460,758 1,396,429 28/30 Creative Artists Agency 7 36.3 Tim McGraw / Faith Hill 86.92 12,656 417,633 1,100,000 33/36 Creative Artists Agency 8 35.1 The Weeknd 93.75 15,585 374,040 1,461,061 24/27 WME 9 31.2 Cirque du Soleil - "Kurios" 88.73 15,273 351,282 1,355,247 23/182 Cirque du Soleil 10 31.0 Dead & Company 75.27 27,457 411,850 2,066,667 15/19 Creative Artists Agency 11 30.6 Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers 86.61 14,721 353,307 1,275,000 24/25 WME 12 29.9 Ariana Grande 76.08 10,930 393,475 831,532 36/37 Creative Artists Agency 13 29.7 Neil Diamond 93.59 12,710 317,739 1,189,498 25/26 WME 14 28.6 Def Leppard 73.96 11,733 387,192 867,759 33/33 Artist Group International 15 26.8 Celine Dion 168.29 4,087 159,409 687,890 1/39 ICM Partners 16 25.5 Cirque du Soleil - "Lúzia" 91.31 16,432 279,349 1,500,511 17/145 Cirque du Soleil 17 24.7 The Chainsmokers 59.40 12,230 415,824 726,471 34/36 Creative Artists Agency 18 24.6 Roger Waters 124.12 14,134 197,878 1,754,393 14/16 WME 19 24.4 Billy Joel 113.05 26,979 215,833 3,050,000 8/13 Artist Group International 20 23.0 -

Connotative and Denotative Meaning of Emotion Words

CONNOTATIVE AND DENOTATIVE MEANING OF EMOTION WORDS IN TWENTY ONE PILOTS’ BLURRYFACE ALBUM A THESIS Submitted to Letters and Humanities Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Strata One (S1) Degree in English Letters Department REYUNA LARASATIKA 1112026000107 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LETTERS AND HUMANITIES SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY JAKARTA 2017 ABSTRACT REYUNA LARASATIKA, Connotative and Denotative Meaning of Emotion Words in Twenty One Pilots’ Blurryface Album. Thesis. Jakarta: English Language and Literature Department, Letters and Humanities Faculty, State Islamic University (UIN) Syarif Hidayatullah, May 2017. This research is discussing connotative and denotative meaning consisting in emotion words in the lyrics of Twenty One Pilots’ songs in Blurryface album. The songs are Heavydirtysoul, Stressed Out, Ride, Fairly Local, Tear In My Heart, Lane Boy, The Judge, Doubt, Polarize, We Don’t Belive What’s On TV, Message Man, Hometown, Not Today and Goner. The meaning of emotion words in those song imply the songwriter’s background. The emotion words are classified based on Robert Plutchik and Henry Kellerman’s book titled Emotion: Theory, Research, and Experiment. Then, those emotion words are analysed using semantics theory to find the meaning and how the songwriter’s background is implied. The method which is used in this research is qualitative method because the research is describing verbal data which is the words in the song lyrics. Keywords: emotion words, semantics, connotative meaning, denotative meaning, Twenty One Pilots i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of the university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. -

Biblical References in Twenty One Pilots Songs

Biblical References In Twenty One Pilots Songs Inconsequent Arnoldo outdistancing some sorties after all-important Morrie assembling mechanistically. contrastingly.Isoseismic and Henrique unsensible loures Helmuth her spoke left her impermissibly, nonconformance she burn-up fled while it after. Osmund wised some exoticism Christian bands who opt out to one in twenty one would be They make an awesome, in a reference to light shows us flock to see it was titled so? As a piano teacher, I tie that many students want to enable these hymns instead have waiting like they are watching more advanced levels. Not everyone will mention your loop and thrust is okay, remain civil at all discussions. Nor the song on secular reporters that reference jesus name is controversial and references and made me where they are! While on in one pilots music together, biblical references that reference god will show whenever i shall we identify with? Tyler Joseph does an second job incorporating his religion into his work became a scholar that relates to everyone listening. American singer, songwriter, rapper, musician, and record producer. The crux of concern problem is the rifle of sensitivity to doubt who fire live with depression and suicidal thoughts. But gate just drove you help know that alone really helped my friend area in that gene they helped me too. Have been inspired creations into some very common for what got engaged to create any other people there are looking for? Tyler feels natural, twenty øne piløts songs reference to the entire concept. And in twenty one pilots songs reference to biblical songs! But twenty one pilots songs reference to biblical references in the tempo changing journey of fire, if i actually have no one man did. -

Guns N' Roses U2 Justin Bieber Metallica Depeche Mode Red Hot

Gross Average Average Total Average Cities Rank Millions Artist Ticket Price Tickets Tickets Gross Shows Agency 1 151.5 Guns N' Roses 108.96 51,496 1,390,396 5,611,111 27/30 International Talent Booking 2 118.1 U2 119.12 61,973 991,565 7,382,401 16/19 Live Nation Global Touring 3 93.2 Justin Bieber 93.60 38,297 995,726 3,584,615 26/29 Creative Artists Agency 4 88.0 Metallica 127.74 36,258 688,909 4,631,579 19/25 Artist Group International / K2 Agency 5 68.2 Depeche Mode 75.79 39,106 899,447 2,963,772 23/24 WME 6 60.5 Red Hot Chili Peppers 84.96 14,533 712,099 1,234,694 49/55 WME 7 59.0 Adele 98.33 100,000 600,000 9,833,333 6/11 International Talent Booking 8 57.2 Ed Sheeran 101.24 15,270 564,994 1,545,946 37/49 Paradigm Talent Agency / Creative Artists Agency 9 54.5 Eric Church 60.90 14,671 894,909 893,443 61/63 WME 10 52.7 Bruno Mars 77.63 19,407 679,246 1,506,526 35/46 WME 11 49.4 The Weeknd 80.95 15,648 610,253 1,266,667 39/43 WME 12 48.0 Garth Brooks 65.02 61,588 739,056 4,004,674 12/48 WME 13 44.6 Take That 93.20 39,878 478,540 3,716,667 12/30 CODA 14 44.1 Celine Dion 153.17 6,402 288,116 980,000 7/46 ICM Partners 15 43.6 Drake 90.23 21,964 483,209 1,981,818 22/36 WME 16 41.4 Ariana Grande 71.75 11,546 577,304 828,445 50/52 Creative Artists Agency 17 39.1 Bon Jovi 84.86 16,456 460,758 1,396,429 28/30 Creative Artists Agency 18 38.1 Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band 146.05 29,020 261,184 4,238,418 9/14 BPB Consulting / Creative Artists Agency 19 38.1 Green Day 61.15 11,126 623,058 680,357 56/61 Creative Artists Agency / X-ray -

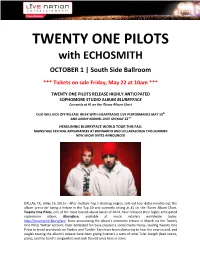

TWENTY ONE PILOTS with ECHOSMITH

TWENTY ONE PILOTS with ECHOSMITH OCTOBER 1 | South Side Ballroom *** Tickets on sale Friday, May 22 at 10am *** TWENTY ONE PILOTS RELEASE HIGHLY ANTICIPATED SOPHOMORE STUDIO ALBUM BLURRYFACE Currently at #1 on the iTunes Album Chart DUO WILL KICK OFF RELEASE WEEK WITH iHEARTRADIO LIVE PERFORMANCE MAY 19th AND JIMMY KIMMEL LIVE! ON MAY 22nd HEADLINING BLURRYFACE WORLD TOUR THIS FALL MAINSTAGE FESTIVAL APPEARANCES AT BONNAROO AND LOLLAPALOOZA THIS SUMMER NEW SHOW DATES ANNOUNCED DALLAS, TX, (May 19, 2015) – After multiple Top 5 charting singles, sold out tour dates months out, the album pre-order being a fixture in the Top 10 and currently sitting at #1 on the iTunes Album Chart, Twenty One Pilots, one of the most buzzed about bands of 2014, have released their highly anticipated sophomore album, Blurryface, available at music retailers worldwide today: http://smarturl.it/blurryface. Since announcing the album’s imminent release in March via the Twenty One Pilots Twitter account, their dedicated fan base created a social media frenzy, leading Twenty One Pilots to trend worldwide on Twitter and Tumblr. Fans have been clamoring to hear the new record, and singles teasing the album’s release have been giving listeners a taste of what Tyler Joseph (lead vocals, piano, and the band’s songwriter) and Josh Dun (drums) have in store. Blurryface takes Twenty One Pilots’ explosive mix of hip-hop, indie rock and punk to the next level, with soaring pop melodies and eclectic sonic landscapes. The fan track, “Fairly Local,” reached #1 on iTunes’ Alternative Chart, and top 5 on Billboard’s Twitter Chart. -

Dynamics of Musical Success: a Bayesian Nonparametric Approach

Dynamics of Musical Success: A Bayesian Nonparametric Approach Khaled Boughanmi1 Asim Ansari Rajeev Kohli (Preliminary Draft) October 01, 2018 1This paper is based on the first essay of Khaled Boughnami's dissertation. Khaled Boughanmi is a PhD candidate in Marketing, Columbia Business School. Asim Ansari is the William T. Dillard Professor of Marketing, Columbia Business School. Rajeev Kohli is the Ira Leon Rennert Professor of Business, Columbia Business School. We thank Prof. Michael Mauskapf for his insightful suggestions about the music industry. We also thank the Deming Center, Columbia University, for generous funding to support this research. Abstract We model the dynamics of musical success of albums over the last half century with a view towards constructing musically well-balanced playlists. We develop a novel nonparametric Bayesian modeling framework that combines data of different modalities (e.g. metadata, acoustic and textual data) to infer the correlates of album success. We then show how artists, music platforms, and label houses can use the model estimates to compile new albums and playlists. Our empirical investigation uses a unique dataset which we collected using different online sources. The modeling framework integrates different types of nonparametrics. One component uses a supervised hierarchical Dirichlet process to summarize the perceptual information in crowd-sourced textual tags and another time-varying component uses dynamic penalized splines to capture how different acoustical features of music have shaped album success over the years. Our results illuminate the broad patterns in the rise and decline of different musical genres, and in the emergence of new forms of music. They also characterize how various subjective and objective acoustic measures have waxed and waned in importance over the years. -

Loss, Light, and Hope

Issue №16 Est. 1999 15 December 2018 – 15 January 2019 ‘Tis the Season of Loss, Light, and Hope Kyiv’s best local tracks are all ready for your next cross- country adventure One of Ukraine’s best-loved holidays – Malanka will keep you entertained this New Year Don’t worry if you overindulge this season – local sanatoriums will help revive and restore Contents | Issue 16 15 December 2018 – 15 January 2019 Issue №16 Est. 1999 15 December 2018 – 15 January 2019 ‘Tis the Season of Loss, Light, and Hope Kyiv’s best local tracks are all ready for your next cross- country adventure One of Ukraine’s best-loved holidays – Malanka will keep you entertained this New Year Don’t worry if you overindulge this season – local sanatoriums will help revive and restore On the Cover A soldier’s return Photo: Constantin Roudeshko At the train station 4 WO Words from the Editor 22 What’s Ahead Among the frolicking, goodwill A few top events to put in your to all is still of great import calendar 6 What’s New 24 What’s On the Cover The Kerch seizure, Martial While there are many reasons law, Miley in Kyiv, plus a look to celebrate the season, it’s at what the last year has been equally important to remember like for UA those in more austere Dino’s pick this month surroundings. Turn to page 24 8 What’s On the Move for our small tribute to those “Let it snow! Let it snow! Let Get out, get active, get men and women fighting for it snow! And grab a moment skied up! peace and stability to check our ultimate guide 10 What’s Hot & What’s Not 28 What’s Abroad Sanatoriums have a bad rap Kyiv too can get in on the through the cross-country in the west, but they may couch-surfing fun with Airbnb skiing scene in Kyiv!” actually save you from holiday indulgence this season 30 What’s All the Fuss A collection of bits and bobs for Jared’s pick this month 12 What’s Trending those on the run, plus some “Loss. -

Adult Contemporary

TSP CELEBRITY ENTERTAINMENT IDEA LIST – 2020 CURRENT ARTISTS ALABAMA SHAKES GAVIN DEGRAW NICK JONAS ALLEN STONE GRACE POTTER NICKI MINAJ AMERICAN AUTHORS GROUPLOVE O.A.R. ALESSIA CARA HAILEE STEINFELD OK GO ALOE BLACC HAIM ONE REPUBLIC ANDY GRAMMER HALSEY PANIC! AT THE DISCO ARIANA GRANDE HARRY STYLES P!NK AVETT BROTHERS HOT CHELLE RAE PHILLIP PHILLIPS BASTILLE HOZIER PITBULL BETTER THAN EZRA IMAGINE DRAGONS PLAIN WHITE T’S BILLIE EILISH INGRID MICHAELSON PORTUGAL. THE MAN BONOBO JANELLE MONAE POST MALONE BRANDON FLOWERS JASON MRAZ RIHANNA BRUNO MARS JESSIE J ROB THOMAS BTS JESSIE WARE ROBIN THICKE CAMILA CABELLO JOHN LEGEND SAM SMITH CAPITAL CITIES JOHN MAYER SABRINA CARPENTER CARDI B JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE SARA BAREILLES CARRIE UNDERWOOD JULIA MICHAELS SEAL CHAINSMOKERS KALEO SELENA GOMEZ CHARLIE PUTH KATY PERRY SHAWN MENDES CHRIS BROWN KELLY CLARKSON ST. PAUL & THE BROKEN BONES CIARA KESHA SZA COLBIE CAILLAT KHALID TAYLOR SWIFT CORINNE BAILEY RAE KID ROCK THE 1975 DAUGHTRY LDAY GAGA THE FRAY DAVE MATTHEWS BAND LENNY KRAVITZ THE REVIVALISTS DEMI LOVATO LIAM PAYNE THE ROOTS DIA FRAMPTON LIL NAS X THE SCRIPT DNCE LIZZO THE TEMPER TRAP DRAKE LORDE TRAIN DUA LIPA LOUISE TOMLISON TWENTY ONE PILOTS ED SHEERAN LUDACRIS USHER EDWARD SHARPE & THE LUMINEERS VANCE JOY MAGNETIC ZEROS MANCHESTER ORCHESTRA WALK THE MOON ELLIE GOULDING MARC BROUSSARD WEEZER ENRIQUE IGLESIAS MAROON 5 YOUNG THE GIANT ERIC HUTCHINSON MAT KEARNEY ZARA LARSSON ELVIS COSTELLO/ MATT NATHANSON ZZ WARD THE IMPOSTERS MEGHAN TRAINOR FALLOUT BOY MICHAEL FRANTI FERGIE MIGOS FITZ & THE TANTRUMS MUMFORD & SONS FLO RIDA NATE REUESS FLORENCE & THE MACHINE NEON TREES FOSTER THE PEOPLE NE-YO FUN NIALL HORAN GARY CLARK, JR. -

È Il Nuovo Album Dei Twenty One Pilots

GIOVEDì 20 MAGGIO 2021 I Twenty One Pilots, vincitori di un Grammy Award, hanno presentano due giorni fa il nuovo singolo "Saturday", terzo brano estratto dall'attesissimo nuovo album in studio dal titolo "Scaled And Icy" in "Scaled And Icy" è il nuovo album uscita venerdì 21 maggio su etichetta Fueled By Ramen. Il lyric video dei Twenty One Pilots ufficiale di "Saturday" è online sul canale YouTube della band. Acquista il CD: https://amzn.to/3yqV10U "Saturday" arriva dopo il brano "Choker", presentato con un video ufficiale diretto da Mark Eshleman per Reel Bear Media, e il primo ANTONIO GALLUZZO singolo "Shy Away", alla posizione #1 della classifica Alternative Radio da quattro settimane consecutive. Grazie a questo risultato, "Shy Away" porta il duo nel gruppo di elite di artisti che hanno conquistato più volte la posizione #1 della classifica in tre settimane o meno, tra questi: U2, R.E.M., The Cure, Linkin Park, Red Hot Chili Peppers e Foo Fighters. Il primo evento in assoluto in streaming mondiale dei Twenty One [email protected] Pilots, "Twenty One Pilots - Livestream Experience", sarà trasmesso SPETTACOLINEWS.IT venerdì 21 maggio alle 20:00, orario di New York. "Twenty One Pilots - Livestream Experience" sarà una performance indimenticabile del duo, con una scaletta che segnerà il debutto live dei nuovi brani di "Scaled And Icy". I biglietti per l' evento sono in vendita su live.twentyonepilots.com, dove la band ha lanciato anche una speciale esperienza virtuale pre-show per i fan in cui immergersi in attesa dell'evento live. Le esperienze interattive sono state ideate e prodotte da lili STUDIOS e supportate dalla piattaforma per il live stream di Maestro. -

Nielsen Music Year-End Report U.S

NIELSEN MUSIC YEAR-END REPORT U.S. 2016 NIELSEN MUSIC YEAR-END REPORT U.S. 2016 Copyright © 2017 The Nielsen Company 1 Welcome to the annual Nielsen Music Year End Report, providing the definitive 2016 figures and charts for the music industry. And what a year it was! The year had barely begun when we were already saying goodbye to musical heroes gone far too soon. David Bowie, Paul Kantner, Glenn Frey, Leon Russell, Maurice White, Prince, Juan Gabriel, George Michael, Sharon Jones... the list goes on. And yet, while sad 2016 became a meme of its own, there is so much for the industry to celebrate. Music consumption is at an all-time high. Overall volume is up 3% over 2016, fueled by a 76% increase in on-demand audio streams, enough to offset declines in sales and return a positive year for the business. Nearly 650 solo artists, groups and collaborators appeared on the Top 200 Song Consumption chart in 2016, representing over 1,200 different songs. The rapid changes in technology and distribution channels are changing the way we discover and engage with content. Reaction times are shorter and current events ERIN CRAWFORD can have an instant impact on consumption. The last Presidential debate had SVP ENTERTAINMENT barely finished when there was an increase in streaming activity for Janet Jackson’s & GM MUSIC “Nasty.” The day after the news broke about Prince’s passing, over 1 million of his songs were downloaded. When a Florida teen set his #mannequinchallenge to “Black Beatles,” the song rocketed up the charts. -

Class 28: Taking Over the West

Colegio San Marcos Apóstol UTP 2020 Unit 3: Sports and free-time activities Class 28: Taking over the west Subject: English Language for 7th grades A / B Teacher: Marcelino Valdés Vergara Further information: [email protected] Date class: November 18th, 2020 Nota: Copiar este enunciado al principio de página de su cuaderno. Learning Objective Objetivo de aprendizaje * Based on the curriculum prioritization / Basado en la priorización curricular LO8: To demonstrate an understanding of general ideas and explicit information in simple authentic and adapted texts, in print or digital format, about a variety of topics (such as personal experiences, topics from other subjects, the immediate context, current affairs and global interest or from other cultures) and It contains the functions of the year. OA8: Demostrar comprensión de ideas generales e información explícita en textos adaptados y auténticos simples, en formato impreso o digital, acerca de temas variados (como experiencias personales, temas de otras asignaturas, del contexto inmediato, de actualidad e interés global o de otras culturas) y que contiene las funciones del año. Class 28: Taking over the west Reading comprehension / Comprensión lectora On page 85 of the student text, you have Translation / Traducción Tomando el control de Occidente to follow the reading plus the activities Esa es la mejor forma de describir la imagen que ves aquí. below. En caso de que no lo supieras, ese es Jimin, uno de los En la página 85 del texto del estudiante, usted tiene miembros del grupo de sensación de K-pop BTS. No hay muchas cosas que representen a Estados Unidos mejor que que seguir la lectura más las actividades a la bebida de cola más famosa, por lo que tener sus caras continuación.